If beer goggles are the standard justification for regrettable decisions made when the bars close, perhaps the culprit that late Tuesday night in August 1993 could be called beer GPS. Our “current location” was the Deep Eddy Cabaret, a bait shop turned friendly tavern in Austin. With last call decreed, a buddy and I raced to finish our final pitcher of Lone Star as the jukebox kicked into Nat King Cole’s version of “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66.” The lightbulb that went off above our heads was visible even in the bar-time floodlight. He said he knew a couple girls in L.A. I said I had a buddy who was renting a Hollywood mansion from the drummer for Ratt. “Road trip,” we said in unison.

My consort was Charlie Robison, then fronting his first band, the Millionaire Playboys. The name was aspirational, but he’d already made the leap to rock star in his mind, seldom going to bed before sunrise or alone. I occupied a spot at the other end of the spectrum, fresh out of law school but, more to the point, nursing a broken heart for a girl I’d wanted to marry. She’d dumped me on New Year’s Eve, and I’d then embarked on a twelve-month bender, living out 1993 as if it were one long Tom Waits song. Charlie and I made the perfect team: the self-styled Dream of the Everyday Housewife and the Lovelorn Loser.

But the Dream didn’t own a reliable car, so our carriage was a Volkswagen Rabbit convertible with peeling red paint I’d recently bought from a poetry student for $1,600. Dubbed the Flame, it had no AC and no stereo, so our first stop was to pick up a jam box from one of Charlie’s girls. He grabbed cassettes by the Clash and the MC5. I opted for John Prine’s divorce album. Otherwise we packed light. Charlie brought a porkpie hat and two silk vests, which he insisted on wearing without shirts. I grabbed my two lucky T-shirts, thinking they might be handy when we went looking for ladies.

By 4 a.m. we were barreling through the darkened Hill Country on U.S. 290 and predicting great things for the song and short story we’d eventually make of the trip. The mood changed somewhere on I-10 as the sun climbed high over lonely desert scrub. The hangovers hit near Ozona, followed soon by a merciless heat that broiled the black vinyl roof and poured through the open windows. By Fort Stockton we were miserable. I don’t think we spoke once through the 240 miles between there and El Paso. We didn’t need to. We could smell the bad decision we’d made.

But there was no turning back; we’d performed too many Jack Kerouac impersonations on friends’ answering machines from gas station pay phones. With another day on I-10 absolutely unthinkable, we had to reroute, to find a closer landmark that would still justify the trip. We chose the Grand Canyon and put our faith in that adage about the journey outweighing the destination.

We drove into Juárez and took tequilas at the fabled Kentucky Club. We knew none of its history but were duly impressed by the waiters’ white jackets and the fact that there was a latrine in the floor at the foot of the bar. Then, at a truly seedy lounge called the Cave, a bartender gave us lessons on swallowing razor blades before, more successfully, teaching us how to say, “¿Tiene cables?”—apparently I’d left the Flame’s headlights on when we parked.

The next night found us at a table of girls in a Tucson bar where Charlie charmed and I flailed. Incensed, he pulled me aside. “Look, freak, don’t offer them a ride to the next bar. Be a jerk. That’ll make them want you.” He raised a better point when he instructed me not to dry my face with toilet paper after washing in a men’s room, especially if I hadn’t shaved in a few days. He said the reason he’d struck out with a comely young Tucsonan named Scout was because my face looked as if it was covered in plaster of paris.

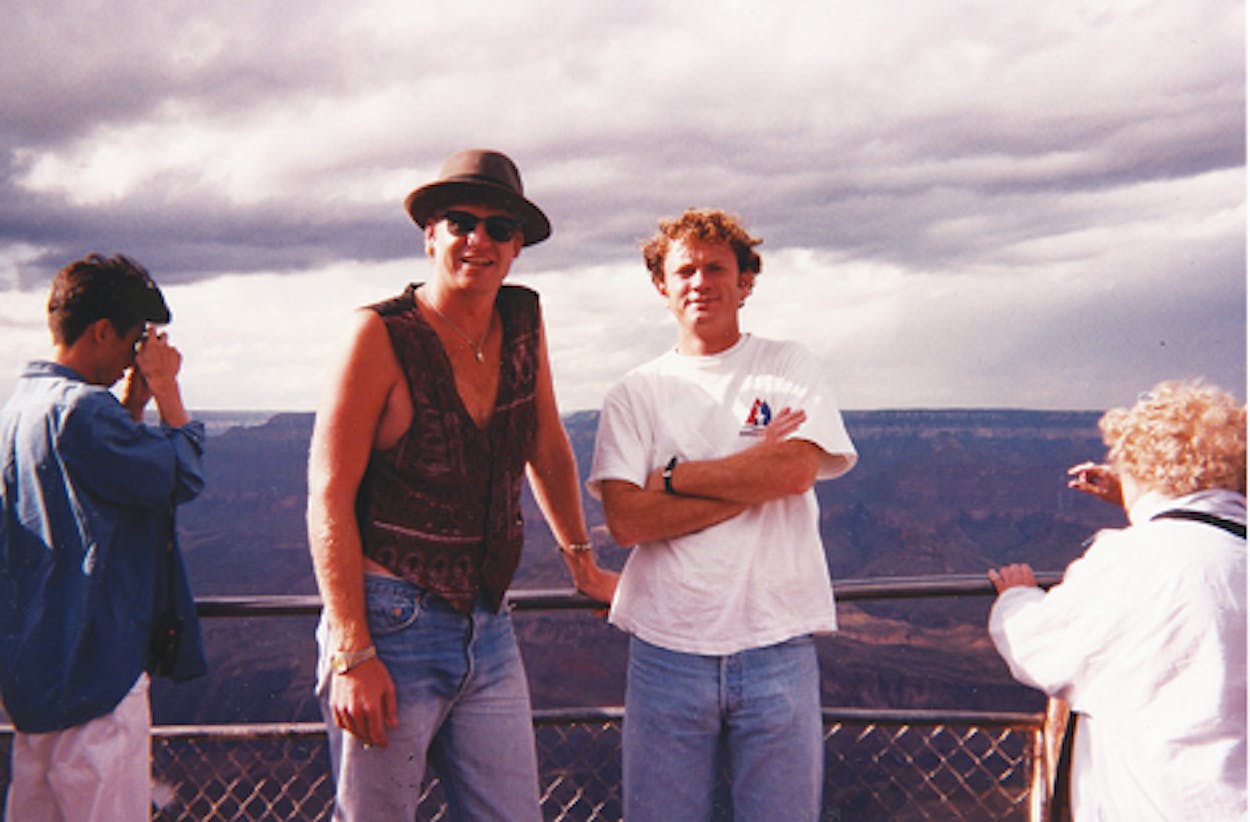

The third afternoon—or was it the fourth?—we approached the canyon and validation, but not necessarily of what we’d intended. A biblical rainstorm appeared just north of Flagstaff, and we were unable to see past the car hood the final fifty miles. Water streamed through the roof, threatening ruin to Charlie’s vest. But then, literally as we pulled into a parking space at the Grand Canyon Village, the clouds cleared. We hustled to an observation point and pushed past other tourists for spots at the rail. Neither of us had ever been there, and neither could talk. I didn’t sense the humbling insignificance I’d heard others describe. Instead I felt shock that I’d never before made the trip. And then I felt lucky. The biggest rainbow I’d ever seen bent up and out of the middle of the gorge. At its bottom, more black clouds were flashing with lightning. We watched awestruck as they rolled up the canyon walls to drench us in sheets of water. Charlie said something about being terrified of lightning and scrambled to the Village saloon. I stood in the rain and watched the fireworks for a good half hour.

The 1,100 miles home were a bleary return to form. We spent a night hot-tubbing in Santa Fe with the alleged “nympho roommate” of a mutual friend. She asked if we minded if she took off her top; Charlie intimated that if I didn’t disappear immediately he’d drown me. I refused. The next morning, over migas and margaritas, she and I decided to ditch him for an afternoon pub crawl. He found us six hours later at a bar called the Bull Ring. I was poised to lean in for a sloppy barfly kiss when he grabbed me by the throat and dragged me out the door. The year’s scoreless-inning streak remained intact.

It was now Sunday night. He needed to be back in Austin to pay his utility bill on Monday or his electricity would be cut off. And he had a guitar-pull gig that night. We drove straight home and later met up at the show. Between songs I screamed for him to play “Six Days on the Road,” an old trucker song that was our new anthem. And between sets we told our friends about the greatest road trip ever taken.