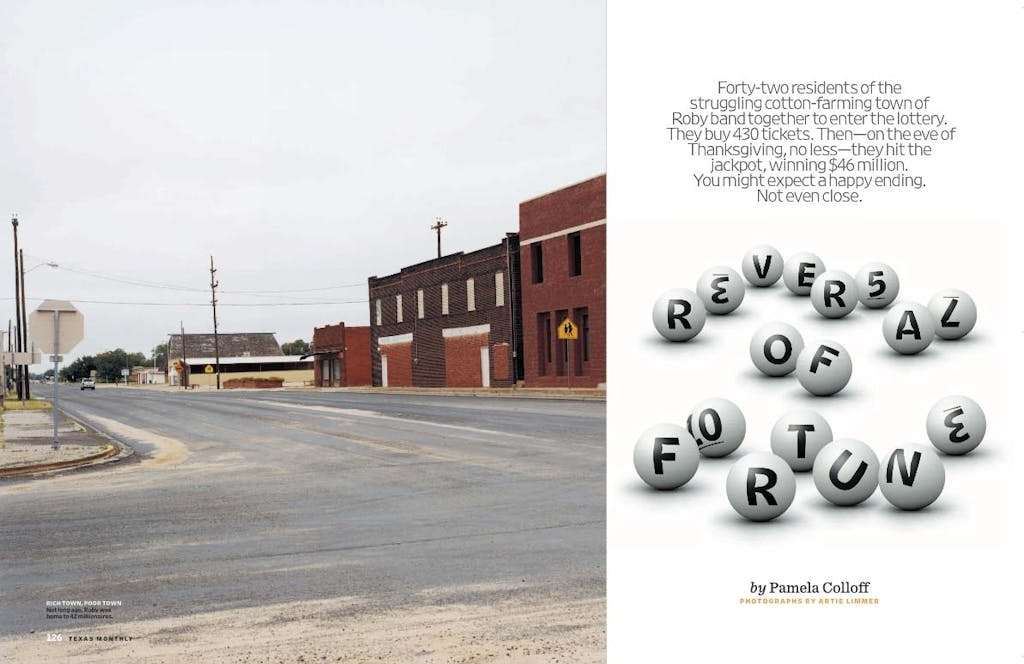

Lance Green hates feeling lonely, and Roby, the West Texas town where he has lived all his life, is a lonely sort of place. On the empty stretch of U.S. Highway 180 that runs through town, most of the mom-and-pop stores have gone broke. Weeds poke through the cracked windows of the Oasis Motel, and the Boll Weevil Cafe, which is vacant, wears the same “For Sale” sign it has for years. At the boarded-up movie house, where the last film played in 1955, a poster of High Noon still hangs below the old marquee; Gary Cooper keeps watch, as he has for an eternity, over the deserted courthouse square. Sometimes Lance will glance down the highway, past the blinking red stoplight, and realize that his pickup is the only car on the road.

Lance stood outside the break room of the cotton gin one morning this summer, wearing a beat-up gimme cap, jeans, a work shirt, boots, and a bittersweet grin. The sky was clear and blue, and the hot temperature, coming right after a hard rain, he said, was good for growing cotton. Lance has short-cropped brown hair, blue eyes, and an easy manner, and he is well liked around town; in high school, which he still talks about a little wistfully, he was the star running back for the Roby Lions and was named Class Favorite his senior year. “I hope that in future years you widen your horizons and leave Roby,” a girl wrote in his high school yearbook, The Tumbleweed, nineteen years ago, but he never has. He became the mayor of Roby at 31—the youngest in the town’s history—and at 37, many of his constituents still call him “a good kid.” His monthly mayoral salary of $35 doesn’t go far, so most days he manages Terry’s Gin, one block east of the courthouse square, and he pours concrete and sells tombstones on the side. That morning he looked out at the meager view that the town afforded, which was beautiful to him. “Everything a man could ever want is right here,” he said. “Besides, where else would I go?”

Lance had hoped for a different future for Roby when, on Thanksgiving Day, 1996, his hometown suddenly became the focus of international attention. The previous day, a group of Roby farmers had pooled their money at the cotton gin to buy lottery tickets, and, improbably, in the middle of a drought that was forcing some of them to file for bankruptcy, they had won the $46 million prize. “A Little Town in Texas Hits the Jackpot,” “Cotton Town Baled Out by Mega Bucks,” and “Texas Town of 600 Suddenly Has 43 Millionaires,” read the headlines. One TV newsman noted that the town of Roby had “more millionaires per capita than the Kingdom of Brunei.” Film crews from as far as Japan and Germany trained their cameras on Roby’s weathered farmers, asking them when they planned on buying their wives Cadillacs and diamond rings, and Hollywood came calling, offering cash for the rights to their life stories. In nearby Sweetwater, car salesmen hurried out of their showrooms to shake hands with prospective buyers who were rumored to be part of the “Roby 43.” When one family went to the Fort Worth livestock show wearing jackets with “Roby” printed on them, strangers approached wanting to touch them for good luck.

The lottery was the biggest thing that had happened in Roby since Bob Terry, on a whim, flew his crop-dusting plane under the blinking red stoplight and right over a state trooper’s patrol car, in 1968. But once the lottery winners drew their first checks and the media circus subsided, nothing much changed. Roby continued its slow decline, the drought wore on, and more than half a dozen businesses went under. The ceremonial check from the Texas Lottery Commission for $46,661,981.13 still hangs, half forgotten, in a corner of the Circle D convenience store—the only evidence that Roby was lucky once. Among the customers who trickle into Wynelle’s Beauty Shop and the Silver Star Cafe, the conversation centers, as it always has, on the vagaries of the weather. The lottery is a sore subject; for each winner in town who came out ahead, another was visited by inexplicable misfortune. Lance was one of Roby’s instant millionaires, and he has had his share of heartache over it. As we talked, he studied the empty town before him and said, “For all the trouble the lottery brought on me, I don’t know whether to be happy I won or sorry I didn’t.”

BEFORE HEADING TO THE COTTON fields each morning, farmers meet just after dawn at Grace’s, a quiet diner on Highway 180 where western music plays on the radio and the deep fryer gurgles in the background. The Breakfast Club, as its members call themselves, includes a dozen or so men in their fifties and sixties who, over plates of biscuits and gravy, talk shop and chortle at one another’s old jokes, occasionally glancing through the cafe’s picture window, searching the sky for rain. This summer the conversation invariably drifted toward the latest health update of a man named Gene Shipp, who had been attacked by a swarm of bees and stung more than two hundred times before having two heart attacks at the hospital. “A damn shame,” the farmers said, shaking their heads. At eight o’clock each morning, they take their last swigs of black coffee, slide on their hats, and head for the door. “How many people do you know who’ve been doing the same job for fifty years and still work every day?” Mike Terry asked me one morning as he rose from one of the Naugahyde booths to go check on his cotton. “We’re still doing it, and I guess we’ll do it till the day we die, because when you’re a cotton farmer, that’s how long it takes to get out of debt.”

The men at Grace’s remember a different Roby, a Roby where cotton was a cash crop and a farmer could provide his family with a decent living when he had a hundred acres to plow. The town was founded in 1885 by cotton farmers from Mississippi and was a thriving outpost until the fifties, when it had sixty businesses and a year-round population of 1,040. “When we used to come to town on a Saturday night, you couldn’t find a place to park,” said Gene Terry, the 69-year-old patriarch of Roby’s biggest clan. “There was the dangedest crowd. Cotton pickers came from the Valley and East Texas every fall, and they would triple or quadruple the population. On Saturday nights the stores stayed open late, and you could barely make your way down the sidewalk. We had Gene Autry pictures at the movie house and a cafe with hamburgers you could buy for a quarter. We had a nice little town.” He and the other farmers at Grace’s can reel off a list of places around town that have since vanished. Nine gas stations. Eight grocery stores. Seven beauty shops. Six cafes. Three motels. Two car dealerships. Two truck stops. Two pharmacies. Two hardware stores. Two churches. Two lumberyards. A hospital. A pool hall.

Nearly all the cotton harvested in Roby was pulled by hand until the mid-fifties, when suddenly one farmer with a mechanical stripper could do the work of one hundred pickers. Fewer and fewer migrant workers made the journey to Roby after that, and a seven-year drought had already set in. “You could hear the lights going off from ’55 on, when the movie house closed,” remembered Gene Terry’s younger brother Bob. “One by one, these little stores that were extending credit during lean times and struggling to compete with the bigger stores in Sweetwater were going belly-up. The town really started falling off in the seventies. The Ford dealership closed, and the courthouse was torn down.” On the main square had stood an elegant three-story courthouse made of limestone and marble—built when Fisher County had modest oil revenue—whose clock everyone set their watches to and whose bell tower could be seen across the prairie from miles away. Bats had taken over part of the courthouse in the early seventies, and the foundation was badly cracked; the county commissioners, who lacked the money to make repairs, called for its demolition. All that remained once the courthouse was razed were chunks of pink marble that were scavenged as souvenirs. A squat, utilitarian brick building was erected in its place, but so few people live in Fisher County now that only two or three trials are held there each year.

By the nineties most of Roby’s third- and fourth-generation cotton farmers who had managed to hold on to their family farms were working fourteen-hour days, six or seven days a week, and were deep in debt, having mortgaged their land more than once avert foreclosure. The rules had changed since their families plowed hundred-acre tracts with a pair of mules. The price of cotton plummeted because of global competition, and the cost of overhead soared; a tractor alone now costs upward of $85,000, and the expense of fixing it once it breaks down can run a farmer more than his yearly income. Roby farmers must now cultivate larger parcels of land for smaller and smaller profits and might spend as much as $300,000 a year to plant cotton on 1,500 acres. Until harvest time, they have no assurances that any money will come back in. The waiting game, which starts during planting season in June and ends in November, puts the whole town on edge. A hard wind or hail or one day too many without rain can ruin a crop. “If there’s a dry spell, we hold a prayer meeting for rain,” said Violet Upshaw, the widow of a longtime cotton farmer. “When it’s dry and dusty and the wind is blowing hard and your cotton won’t grow more than a few inches high and it’s 113 degrees on your back porch, there’s nothing you can do but pray.”

Roby hit the jackpot during a drought, when prayers seemed like they were falling on deaf ears. “That was the year we were fixing to go broke,” said Vernon “Bunny” Terry, Gene and Bob’s youngest brother. Several farmers were on the verge of bankruptcy, and one had already begun to file the paperwork. During a good harvest, cotton burrs skitter across town and the air is so thick with lint that it looks foggy at night through a car’s headlights. But that November 1996, the air was clear and Terry’s Gin was quieter than usual. When the gin’s bookkeeper, Peggy Dickson, suggested one morning that everyone go in on lottery tickets for the $46 million jackpot, it seemed as good an idea as any for salvation.

“IT WAS THE DAY BEFORE Thanksgiving, and Peggy said to me, ‘Lance, we’re going to play the lottery. Give me ten dollars,'” Lance explained to me one afternoon. “I did whatever Peggy told me to, so I said, ‘Yes, ma’am,’ and I handed her ten dollars. Farmers came in all that morning to check cotton prices and drink coffee. And Peggy would say to them, ‘Now, I know playing the lottery is gambling, but we’re going to start a pool. If you’d like to go in on it with us, we’ll need ten dollars apiece.’ The ones that were okay with it got in, and the ones who weren’t stayed out.

“Bunny Terry told Peggy to go to Longhorn Liquor, in Sweetwater, to buy tickets. Bunny said he had a feeling it was going to hit. That was the first time Peggy ever went into a liquor store. She had never had a drink in her life. If her father had been alive, there wouldn’t have been no lottery. He was Church of Christ, very strict. Whatever he said was the law. But she went to Longhorn Liquor that afternoon with $420. The owner threw $10 in for himself and she bought 430 Quick Picks.

“I forgot all about the lottery that night. I was having an argument with my ex-wife. We were less than two weeks away from having our divorce finalized. We had some words with each other on the phone and hung up. The phone rang again, and when I picked it up, I was fixing to start yelling. I heard someone bawling on the other end of the line. It was Peggy. I said, ‘Peggy, what’s wrong?’

“She said, ‘We won.’

“I asked her, ‘Won what?’

“‘Won the lottery.’

“Jimmy Carreon was over at my house, and he fell off the couch when he heard the news. I guess I didn’t know what to think; I was dumbfounded. For about an hour, the phone wouldn’t quit. I drove to the gin hands’ houses that night and told them we’d won. I woke half of them up, and the other half were still cooking for Thanksgiving dinner.

“We had a meeting at the gin the next morning with a lady from the lottery commission. By seven o’clock, there were satellite trucks from all the major networks in town. All the newspapers were here. There were reporters everywhere. They wanted to know if we were going to Paris or if we were going to buy big ranches or quit our jobs. One guy asked me, ‘You gonna buy a Cadillac?’ We were all sitting back, eyeballing the lady from the lottery commission and all these reporters and wondering, ‘What’s going to happen now?’ I didn’t get any rest for a week. I had to go to Abilene four days later to see a movie just so I could take a nap.”

THE ROBY STAR-RECORD RAN just one article about the $46 million windfall: a reprint from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, which it placed below the fold, at the very bottom of its front page, beneath a story whose headline read “Letters to Santa Due on December 17th.” In Roby, it was a delicate news story; the fact that so many citizens had been caught gambling—and had brought international attention to the town by playing the numbers, no less—carried a whiff of impropriety in a community where nearly everyone’s church affiliation is either Baptist or Church of Christ. When it came to light that more than half the deacons at the Roby Church of Christ were lottery winners, three families left the church in protest and parishioners debated whether the gamblers in their midst should be required to tithe their winnings. “That was the only uproar we had,” said church member Foy Mitchell. “Our preacher told us that Sunday that the Good Book says not to judge, and that’s the last he spoke of it.”

By far the biggest prize fell to the Terrys; 21 of the lottery winners were descendants, or spouses of descendants, of the original Terry family, who came to Roby in 1903 and have grown cotton ever since. If there was bitterness among people who had chosen not to buy in or who had simply missed the opportunity (like high school football coach Harold Scott, who had left town to get a haircut) they kept their resentment—and continue to keep it—to themselves. For a town accustomed to the capriciousness of the weather, which can ruin one farmer’s crop with a torrent of hail and spare another’s, the lottery was just another unpredictable variable. Even small-business owner Kenneth Terry wore a stiff upper lip the following week when he was forced to close his hardware store because he couldn’t pay his bills. “Everyone who won was needful, and no one flaunted what they had,” said Violet Upshaw. “We were happy for them and for how it might help our town.”

The jackpot, which came out to $1,085,162 per winner, seemed dazzling at first, and hopes ran high that Roby might be headed for an economic recovery. The actual math was less encouraging; paid in twenty annual installments, the winners took home, after taxes, around $39,000 a year. Any money was a blessing, of course, but for farmers who were sometimes half a million dollars in debt, having leveraged their land to plant cotton that yielded little in return, the lottery did not exactly afford them the extravagant lifestyles of millionaires. Except for Shad Rasco—a farmer’s son whose splurge on a $48,000 Mitsubishi 3000 GT Spyder convertible still raises eyebrows among the Breakfast Club—winners were as practical as they had been during dry spells. They started college funds, fixed leaky roofs, paid off car loans, set aside money for retirement, and traded in old pickups for new ones. The national media, which hung around Roby to see if the winners would throw away their fortunes on flashy Christmas presents, had little to write about, except that the town’s farmers could finally breathe a sigh of relief. “The banks had been working on a bunch of us, and the lottery saved our butts,” Bunny Terry remembered. “We were as happy as we could be. But that money didn’t go into our pockets; it went straight back to the banker. I always said, ‘I’ll win the lottery before I get out of debt farming,’ and I proved that to be true.”

The bad luck began before Christmas. Six days after receiving his first lottery check, a gin employee named Albert Barrera fell asleep at the wheel and hit a guardrail, totaling his brand-new Ford pickup with 812 miles on it. Then Gene Terry’s house burned to the ground in an electrical fire. (“Living in the country’s nice, but it takes the fire department a little while to get there,” he explained.) Most of the winners made the mistake of cutting quick deals with lottery buyout brokers, who offered them cash up front in exchange for their future annual payments; in the end, they were left with about a third of their total winnings. Some sunk all their money into ill-fated business ventures. Richard Spencer, the county’s former agricultural extension agent, lost $250,000 trying to start a cottonseed processing plant in Roby that never turned a profit. But the worst hand fell to Peggy Dickson. A year to the day that the Roby 43 won the lottery, Peggy was diagnosed with brain cancer. “Peggy had terrible headaches that kept getting worse,” Lance said. “We all had a feeling she wasn’t going to make it.” She died a few weeks after her diagnosis, at the age of 49, leaving behind dozens of farmers who owed their livelihoods to her, children who would attend college because of her, and an entire town consumed by mourning.

LANCE LIVES IN A TIDY double-wide on the northeastern edge of town, along a rutted dirt road that leads off of the courthouse square. From his house, the furrowed cotton fields around Roby stretch out toward the ghost towns that dot the rest of the county—Hobbs, Longworth, Pleasant Valley, Stamper, Pleger, and Palava, to name a few. The land is stark and treeless and flat, and when color fades from the landscape during drought time, the view is bleak, except for the wide blue sky above. At night, the only sound that can be heard from Lance’s living room is the wind blowing in off the prairie. Most evenings, he fills in the silences by having his best friend, Opie Nazworth, over for supper. A redheaded cotton ginner with a big, roaring laugh, Opie grills pork ribs and tells wild stories about his days as a sailor and staves off that lonely feeling Lance gets a little while longer. It was a discussion with Opie eight years ago that led Lance to make his first foray into local politics. “I was running my mouth off, sitting on the couch, drinking beer one night,” Lance remembered. “And I said, ‘Why do I have to drive fifty miles to Abilene to buy a pair of pants?’ I was mad Roby was dying and that we were just sitting around, waiting for it to die. I said, ‘Maybe I should run for mayor.’ And Opie said, ‘Well, why don’t you?'”

Cecil King, who owned the bank in town, had been mayor of Roby for thirty years. As his challenger, Lance was a long shot. Lance was young, inexperienced, and not from a prominent family; his father, like his father before him, had poured concrete, not farmed cotton. “Lance is a dreamer, and if you want to try and save a town like Roby, you have to dream,” Richard Spencer observed. “Cecil is a banker; he’s practical. Lance wanted to give everyone some hope.” Lance entered the race four months after winning the lottery and drafted a simple platform: pave Roby’s remaining dirt roads, keep taxes low, obtain alternative sources of water, and aggressively try to bring businesses to town. Campaigns in Roby are a perfunctory affair, without debates or door-to-door politicking, but wherever Lance went that spring he talked to anyone who would listen about his plans for Roby. On Election Day that May, he cast his ballot and then went fishing, preferring to calm his nerves than to sit at the gin waiting for returns. When the results were in, he had lost by two votes: 9698. “Wynelle and I felt terrible, because we had every intention of voting for Lance, and then we forgot it was Election Day,” said Bob Terry. “We cost him the race!”

The defeat was humbling, but Lance had more urgent problems weighing on him. “My ex-wife tried to reconcile with me after I won the lottery,” he explained. “She said she wanted to get back together and work it out. Deep down, I think I knew it wasn’t going to work, but I felt like we should try.” During their three-year marriage, he had raised her daughter, who was born during their courtship, as his own. “I’d always wanted a family, and I loved that little girl,” he said. “We tried to patch things up that Christmas, and January, and February. Finally I realized it wasn’t going to work.” Divorce proceedings resumed, and Lance saw his stepdaughter, who lived thirty miles away with his wife, less and less often. Then came the news that broke him. “The Monday after the election, my ex-wife made the accusation that I had molested my stepdaughter,” he said. “Mom heard in a beauty shop in Anson that they were filing charges against me. She came by the house and told me. The grand jury met the next week, and the indictment came in June. I’d rather be accused of murder—of a triple murder—than a thing like that.”

In Roby, the unofficial verdict was handed down swiftly. “People didn’t believe Lance did it,” said Bob Terry, echoing the comments of many town residents. “They thought he was being railroaded for his money.” In a town where everyone has known one another since birth and the most intimate details of their personal lives are common knowledge, residents found the allegations hard to believe. “If I thought he’d done it, I’d have been the first one with my hand on the rope,” said Opie, who grew up across the street from Lance. “But I know this man.” A medical exam suggested that the three-year-old girl had been sexually assaulted, but no physical evidence was ever found that connected Lance to any crime. The indictment against him was dismissed at a hearing in the spring of 1998, after state district court judge Weldon Kirk interviewed the little girl and found her not competent to testify.

Lance’s ex-wife never increased her monetary demands in the divorce proceedings after the abuse charges were made and settled for less than half the community property in their divorce, but the perception in Roby exists to this day that Lance’s legal troubles befell him because he won the lottery. He was forced to take a cash buyout to pay his bills, running through a substantial amount of his winnings fighting the abuse charges. But it was not the money he cared about. “It’s an accusation that will never go away,” he told me. “People will always wonder, in the back of their minds, if it’s true. I have to live with that every day.” The stress of that year had been enormous, he said: “I nearly drank myself to death over this. I became a hermit after I was indicted, and I never left the house, except when I had to go to work or drive to Austin to talk to a high-powered shrink so he could see what kind of pervert I was.” The pain he feels is twofold, since he will likely never see the girl he raised as his daughter again. “I haven’t seen my stepdaughter since the day those charges were dismissed,” he said. “My attorney told me not to show any emotion when the judge dismissed the charges, just to walk out of the courtroom. No good-byes.”

Roby showed its support in an unusual way. Cecil King had decided a few weeks earlier that he was ready to retire, and the mayor pro tem, Rex Beauchamp, felt that Lance was better suited to the job. With the blessing of the city council, Beauchamp called Lance a few hours after the charges against him were dismissed and asked him to become Roby’s next mayor. He was sworn in that week, and in the past two elections, he has run unopposed. “You just can’t find people like this anywhere else,” Lance said. “During that whole ordeal, people would stop me and say, ‘Boy, are you all right? If you need anything, you just call me.’ I must’ve heard that a hundred times. I know I was on every prayer list there was. People brought food to my house and checked up on me every day. A friend I grew up with quit a $20-an-hour job in San Angelo so he could stay with me for a while and make sure I’d be all right. Hell, that’s good people.”

ONE MORNING IN JUNE, as the sun was breaking over the cotton fields, Lance drove the four blocks from his house to the gin, as he does every weekday morning—a minute-long drive that spans half the town. He started working at the gin the day after he graduated from high school, nineteen years ago, and every morning for the first ten years he worked there he swore would be his last. Then, like so many things, he became accustomed to it. As he turned onto Highway 180, he looked down the length of road, toward the courthouse square, and saw that the town was empty. He parked his pickup outside the gin and pushed open the break room door, which was unlocked. Diesel and fertilizer prices were written on a chalkboard inside, and a plastic American flag was tacked to the wall. Lance made a pot of coffee and turned on the TV, folding a copy of the Abilene Reporter-News to the crossword. A few minutes later, an old man in a white straw hat walked through the door.

“Morning, Junior,” Lance said, glancing up for a moment.

“How you doing?” the farmer said with a nod.

“All right.”

They sat in silence, sipping coffee from white Styrofoam cups as the morning news played softly on the TV. Lance stared at his crossword, which was still full of empty white squares, and frowned. The two men sat and said nothing. Outside, there was no movement on the highway; even the birds were quiet. After a while, the farmer rose to go.

“Y’all have a good day now,” the farmer called out over his shoulder before the screen door slammed behind him.

Eight years later, the lottery hasn’t brought any miracles to Roby. Lance has done what he can as mayor, earning Roby $1 million in state and federal grant money, but its tax base continues to shrink each year, and its sales tax revenue, with just two stores in town, is virtually nil. Even the town’s last grocery store has closed. Roby’s oil revenues have played out, its landscape is too flat for wind power, and its political clout is too small to lobby for a waste dump. Some of the most pressing issues Lance must grapple with as mayor, like vacant houses and stray dogs, are the portents of a place that is emptying out. Farmers’ sons are taking jobs as prison guards in Snyder and Lamesa rather than working the land—or simply leaving Roby for good.

On my last night in town, Lance and Opie threw a few rib-eye steaks on the grill and sat in Lance’s living room, holding forth on Roby’s virtues and the progress of Gene Shipp, the man who had been stung by bees more than two hundred times. “You know what makes this town so great?” Lance said. “Thousands of dollars have been donated to the bank for his medical bills. His kids are eating well. And when he gets out of the hospital, he’s gonna be fed, his house will be clean, and his bills will be paid.”

“Don’t go telling everybody how great this little town is, or they’ll all want to move here,” Opie said.

“We could stand to have some new friends,” Lance pointed out with a grin. “I’ve heard all your stories.”

“Hell,” Opie said, cracking open another beer. “I guess you’re right about that.”

Lance stepped outside to check on the rib eyes and turn them over on the grill. Before heading back inside, he glanced up at the sky and leaned against his pickup for a moment, sucking in his breath. “Look at that sunset,” he said, taking in the view. “What more do you need than this?” He shook his head. “I’ve never really been anywhere in the world—I haven’t traveled like Opie has—but I’ve never loved a place as much. Goddam, it’s just so nice to be home.”