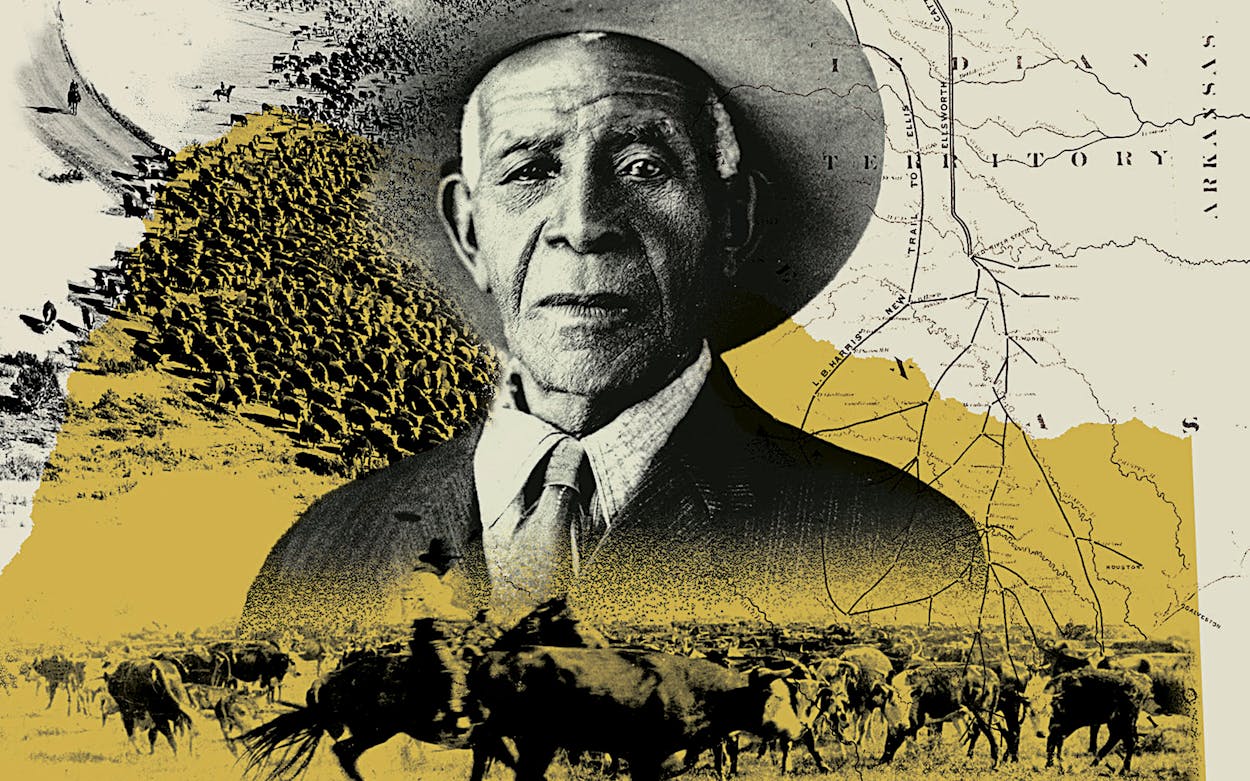

One day in the late 1930s, Daniel Webster Wallace—“80 John,” as he was known in ranching circles—rode his favorite horse, Blondie, from his Mitchell County ranch to the Loraine post office. It was a familiar route for him in this mostly flat, sandy part of the state halfway between Midland and Abilene. He had made the six-mile round trip dozens of times. Wallace collected his mail then walked back to Blondie. In his time, 80 John had broken hundreds of broncs. His tougher-than-bull-hide body had never failed him. But on this day, he lacked the strength to swing his leg over the saddle. A group of men saw him struggling and hustled over to lift 80 John onto Blondie.

Wallace was Black. The men who helped him were white. One might imagine that such a scene would have been jaw-dropping in Depression-era Texas, where white hostility toward people of color was common. But the West Texas cowboy culture of the time was distinctive. Men of different races often supported and respected one another. And no cowboy was more respected than Wallace.

In fact he was one of the most remarkable figures in our history. By the time of his death from influenza and pneumonia in 1939, Wallace had built a West Texas ranch of 8,800 acres and amassed a personal fortune purported to be more than a million dollars—equivalent to about $22 million today. He brought about technical innovations that are still used and devoted much of his savings to strengthening his community—all at a time when it would have been difficult for a white man, much less a Black man born enslaved, to accomplish any of that.

Yet few have heard of him today. Last year I attended the awards banquet at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, in Oklahoma City, at which Wallace was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners, joining such luminaries as Buffalo Bill and U.S. Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor. I pride myself on being knowledgeable about the Old West, but I hadn’t heard of 80 John until that night, nor had many other attendees.

Fourteen members of Wallace’s family were present, and when they arrived, “people were looking at us like, ‘What are you doing here?’ ” says his great-granddaughter Daphne Fowler, who lives on her great-grandparents’ ranch. “But after the banquet, we had all these people coming up to us like, ‘Wow, we had no idea!’ ” The event, she says, was about twenty years in the making. “We have been pushing to get him recognized. And it’s not just recognition for my great-grandfather. There have been a lot of cowboys of color, and their stories don’t get told.”

Larry Callies, founder of the Black Cowboy Museum, in Rosenberg, believes that the Houston region is the birthplace of the American cowboy. “The word ‘cowboy’ itself began being used in Fort Bend County and the surrounding area in 1821,” Callies says. “It was applied to Black slaves who worked with cattle.” (He notes that just as an enslaved person who worked inside the mansion would be referred to as a “houseboy,” one who took care of cattle was referred to as a “cowboy.” Even decades later, the term “cowboy” remained unpopular with white cowpunchers because of its racial connotations.) As early as the 1840s, Black men who were enslaved rounded up free-range Longhorns on the plains west of Houston and drove them north across Indian Territory to Kansas, establishing Texas’s fabled cattle-drive era. 80 John’s story emerges from this rich culture.

He was born in 1860 on a two-hundred-acre farm outside Inez, in Victoria County, not far from the Gulf Coast, to parents who were enslaved. His mother, Mary Wallace, had been bought by the farm’s owners, Mary and Josiah O’Daniel, to serve as a maid and wet nurse. His father, William Wallace, worked as a farmhand. The O’Daniels put young Wallace to work in the fields as a small child, and he received virtually no formal education. “Schools were scarce,” he told his daughter in the 1930s. “I received most of my learning by contact with others and observation.” 80 John and his family remained enslaved until the Juneteenth emancipation announcement, in 1865.

The following year, the O’Daniels moved to a larger farm about eighty miles north, outside Flatonia, taking the Wallace family with them—this time as paid employees. The families maintained ties for the next seventy years; 80 John stayed in touch with the O’Daniels’ sons, M. H. and Dial, until his death.

Mary Wallace saved her coins with the intent of someday buying real estate. The lesson was not lost on 80 John, who from an early age dreamed of owning a spread. He loathed chopping cotton for someone else.

Cattle drives often passed through the area, and Wallace decided they were his escape route, since many of the cowboys he saw were Black. One predawn morning in March 1876, he ran away from the O’Daniel farm and joined a crew moving cattle nearly three hundred miles northwest, to Buffalo Gap. Wallace was a green hand when he departed Flatonia. By the time the herd reached its destination, he had plenty of experience at “trailing.” Thereafter, work was not hard to find.

“He rode for the most famous and respected cattle barons of these seminal days of the Texas cattle industry,” says his great-grandson Alfred McMichael, who, along with his son, Keir, hosts a website devoted to 80 John. “He rode every major cattle trail, from the Chisholm Trail to the Goodnight-Loving Trail. He made long, daring solo rides.” None of it was easy. He contended with thunderstorms, blizzards, droughts, dust storms, outlaw gangs, poisonous snakes, disease, infection, sunstroke, lack of food and water, stampedes, and skirmishes with Native Americans. Once he spent days tracking a handful of Comanches who had stolen one of his favorite horses.

“A friend recommended that I read Lonesome Dove,” McMichael says. “I got a sense of what my great-grandfather’s life on the cattle ranges was like from reading about Joshua Deets.” Deets was the much-respected Black cowboy portrayed by Danny Glover in the TV rendition of Larry McMurtry’s novel. On the other hand, 80 John’s time on the trails was nothing like the world portrayed in the vast majority of Hollywood westerns, in which all of the characters—other than the “evil Indians”—are white.

“Even now, in 2024, a lot of people aren’t aware of how diverse cowboy culture was,” says Robert Tidwell, interim director of collections, exhibits, and research at Texas Tech’s National Ranching Heritage Center, in Lubbock. “The main concern on a ranch is, Can you do the job? Can you pull your own weight? And when that’s the main criteria, you’d be surprised at how things shake out. You had more tolerance than you’d find in other places where social structures were more defined. Between twenty and thirty percent of cowboys were Black.” A comparable number of ethnic Mexicans worked on the cattle trail.

Still, 80 John did occasionally run into racists, and he refused to tolerate them. His daughter Hettye Wallace Branch writes in her book, The Story of “80 John,” that one white man bullied him at a cow camp in West Texas. The six-foot-three 80 John responded by whupping the offender in a fistfight, which apparently instilled respect in his adversary. Improbable as it seems, the two men developed a friendship.

In 1878 a letter informed Wallace that his mother, whom he had not seen since leaving the O’Daniels’ farm, two years earlier, was deathly ill. He hurried back home but arrived too late. He settled his mother’s estate—which included a few acres she had bought—and then returned to West Texas, where he went to work for Clay Mann. Neither man’s life would be the same.

Though largely forgotten now, Mann was a prototype for the white Texas wheeler-dealer. In his time he was a legend in cow camps throughout the West, a figure who had, as a teenager, started a cattle herd and killed his father’s murderer. At one point Mann owned tens of thousands of cattle and thousands of acres in Texas, New Mexico, and Wyoming. He also owned a 600,000-acre ranch in Mexico.

But there was a problem.

“Now, Clay, he liked to drink, and he liked to gamble,” his great-grandson Tom “Possum” Mann tells me. “He loved to play a game called Mexican Monte, which was popular in the West at the time. He might win ten thousand dollars in a night, then lose it the next night.” Mann knew he needed someone in his outfit who was levelheaded and trustworthy. 80 John fit the bill. “80 John didn’t drink or gamble or anything,” Possum says. Soon Wallace and Mann were heading up large drives from Texas to cattle towns throughout the Midwest.

“At the end of a drive,” Possum says, “Clay would pay the hands then give most of the leftover money to 80 John to take back to Clay’s wife, Mary Mann, in Mitchell County. She’d deposit it in the bank he founded in Colorado City. Clay would stay behind with some of the money to gamble and eventually catch a train home.” Mann once gave Wallace $30,000 (the equivalent of $900,000 today) in cash to take to Midland, a three-day ride west from Mann’s ranch. 80 John made sure the money arrived safely.

Mann’s operations were extensive enough that he registered 43 cattle brands, including, most famously, a huge number 80. Wallace oversaw the burning of that brand onto Mann’s stock, and cattlemen associated him with it. “In West Texas,” Tidwell says, “the name ‘John’ was sort of a generic term for cowhands in general.” Hence the nickname 80 John.

Wallace’s expertise extended to more than branding and bronc busting. Mann discovered his top employee was freakishly good at arithmetic. He could add columns of numbers in his head, which proved especially useful when it came to financial transactions. “I have a method of figuring of my own which has stood me in good stead,” 80 John told his daughter. “Very seldom I have missed anything due me any larger than a fraction.” He could also scan a pasture with hundreds of cattle and produce a head count that was usually off by fewer than a dozen animals.

Early in their business relationship, Wallace told Mann that his goal in life was to own land and a herd. Mann began setting aside the lion’s share of 80 John’s pay to accomplish that. Bit by bit, Wallace acquired cattle as he continued working for Mann. Among his other responsibilities, Wallace was the de facto foreman of many of Mann’s properties. Even amid the relative racial comity of cowboy culture it was extraordinarily unusual—perhaps unprecedented—for a Black man to oversee white ranch hands.

In 1885, Wallace had saved enough to buy 1,280 acres of railroad land south of Loraine, intending to homestead it. Realizing he needed to learn how to read and write before he could become a successful rancher, he enrolled as a second grader at a segregated Black school in Navarro County, almost three hundred miles east of his newly acquired land. Over two terms of studying alongside children, he became functionally literate. He also met and fell in love with Laura Dee Owens, a Corsicana beauty who was finishing high school. They were married in 1888 and remained together until his death almost 51 years later. Laura sacrificed her plans to teach in order to help him build a ranch from scratch. They started life as a married couple in a two-room cabin on one of Mann’s ranches.

In 1889, 80 John’s world was turned upside down when Mann died from a stomach hemorrhage, caused by decades of hard drinking. Wallace took charge of the cattle operations and became a father figure to Mann’s sons, teaching them the fundamentals of ranching. The Wallace and Mann families established a bond that continued through generations. (Fowler, Wallace’s great-granddaughter, says Mann’s great-great-granddaughter, Becca Mann George, was her childhood best friend, and they remain close.)

Over the next decades, 80 John and Laura lived as frugally as possible and saved every dime they could to buy more land and cattle. They made for an ideal partnership. He was good with numbers, while she was more verbal. She could parse the thickest contracts and deeds and then read the salient points aloud to her husband. Wallace had a near-photographic memory when it came to business matters. In meeting with lawyers, he could quote passages verbatim that Laura had read to him. She also took charge of treating sick and injured livestock. Whenever 80 John had to be absent to tend to business, she ran the ranch by herself.

“I just can’t imagine,” Fowler says, “what it was like in the late 1800s and early 1900s with that pressure of being the only Black rancher out here. Sometimes I’ll go by the cemetery and I’ll smile thinking about what he and Laura did.”

As early as 1903, Wallace was admitted to the Cattle Raisers Association of Texas and became a highly regarded member. He was, so far as I can tell, the only Black man during that era who was invited to join the group. To attend each year, he had to board a segregated passenger car at the Colorado City railroad station to travel to Fort Worth. He had to find lodging at a so-called colored hotel. From there he walked to the whites-only hotel that hosted the convention. During one of his train trips, some of his white rancher friends joined him for conversation in the segregated passenger car. The conductor attempted to remove the white men, but one refused to budge. “I have known 80 John for thirty years,” the cattleman said. “We ate and slept on the ground together. I see no reason that makes it impossible for me to sit here now.”

The Wallaces eventually lived in a four-room house that 80 John designed and built himself. It has since been moved to the grounds of the National Ranching Heritage Center and restored to its original condition. Wallace disdained automobiles, airplanes, telephones, gramophones, and indoor plumbing. “But he was ahead of his time when it came to raising cattle,” says Mark Merrell, a retired Mitchell County judge and educator. The man who started out herding wild Longhorns ended up crossbreeding Herefords and Durhams (Shorthorns), decades before doing so became commonplace.

He also was an early adopter of windmill technology in West Texas (one of his windmills is on display at the American Windmill Museum, in Lubbock) and created sophisticated concrete watering troughs that other ranchers copied. As the couple became more affluent, they contributed to Mitchell County charities, including paying the construction costs for a Baptist church in Loraine. They also built the Wallace namesake school, in Colorado City, that provided area Black children their only access to education.

In the 1930s, 80 John and Laura drew up a will that put the ranch into a trust. Their primary goal was to provide education funding for subsequent generations of their family. They also wanted to keep the ranch intact. The property is now held by seven trusts. “Each one of the members of the family makes it very specific: don’t sell the land, except to a family member,” says Dwayne Harris, who, as trust officer at City National Bank, managed the ranch for more than twenty years before his retirement. “We had cattle-grazing leases and oil leases as well as revenue from cotton fields, a gravel quarry, and, more recently, wind turbines.” Harris estimates the ranch’s value at $15 million.

It’s said that around the time Wallace made that mail trip on Blondie, he sank a post in the sandy loam on his property and announced he wanted to be buried at that exact spot. The tombstone that now sits in the middle of the family graveyard replaced the post more than eight decades ago. Even facing death, 80 John proved to be a man who knew what he wanted—and achieved it, stampedes and racism be damned.

Austin writer W. K. Stratton’s most recent book is The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film.

Photo Credits: Wallace: courtesy of the Wallace family; cattle drive: Bettmann/Getty; cowboy: Erwin Smith/Library of Congress; map: UNT Libraries/The Portal to Texas History/Hardin-Simmons University Library

This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Immortal Life of “80 John.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- West Texas