Located on the desolate southeastern edge of the small, dusty border town of Del Rio, El Llanito Country Club was never much to look at. It had no clubhouse, no pro shop, no driving range, nor any kind of facilities at all. The parking lot was not filled with fancy cars, because there was no parking lot. And the club’s golf course was in such rough shape that it was only barely indistinguishable from the sunbaked, southwest Texas scrubland from which its nine holes had been carved.

El Llanito is gone now, all but forgotten. The area where it was located, in the vicinity of the present-day intersection of Dr. Fermin Calderon Boulevard and East Garza Street, was long ago developed, covered by sundry small businesses and nondescript single-story houses. Today the area is home to an Exxon gas station, a used car dealership, and a public housing authority. It’s unsurprising, then, that few are aware of what transpired there almost seventy years ago, when El Llanito was founded by a group of young men driven by a singular yet unlikely purpose: the mastery of the game of golf.

Of course, anyone the least bit familiar with the sport knows that it can never be mastered. As the magical caddie Bagger Vance memorably said in the 2000 golf movie The Legend of Bagger Vance, golf is “a game that can’t be won, only played.” In 1950s Del Rio, it couldn’t even be played, if you were the wrong color. The sole course in the city, San Felipe Country Club, was reserved for members only. And all the members were non-Hispanic whites.

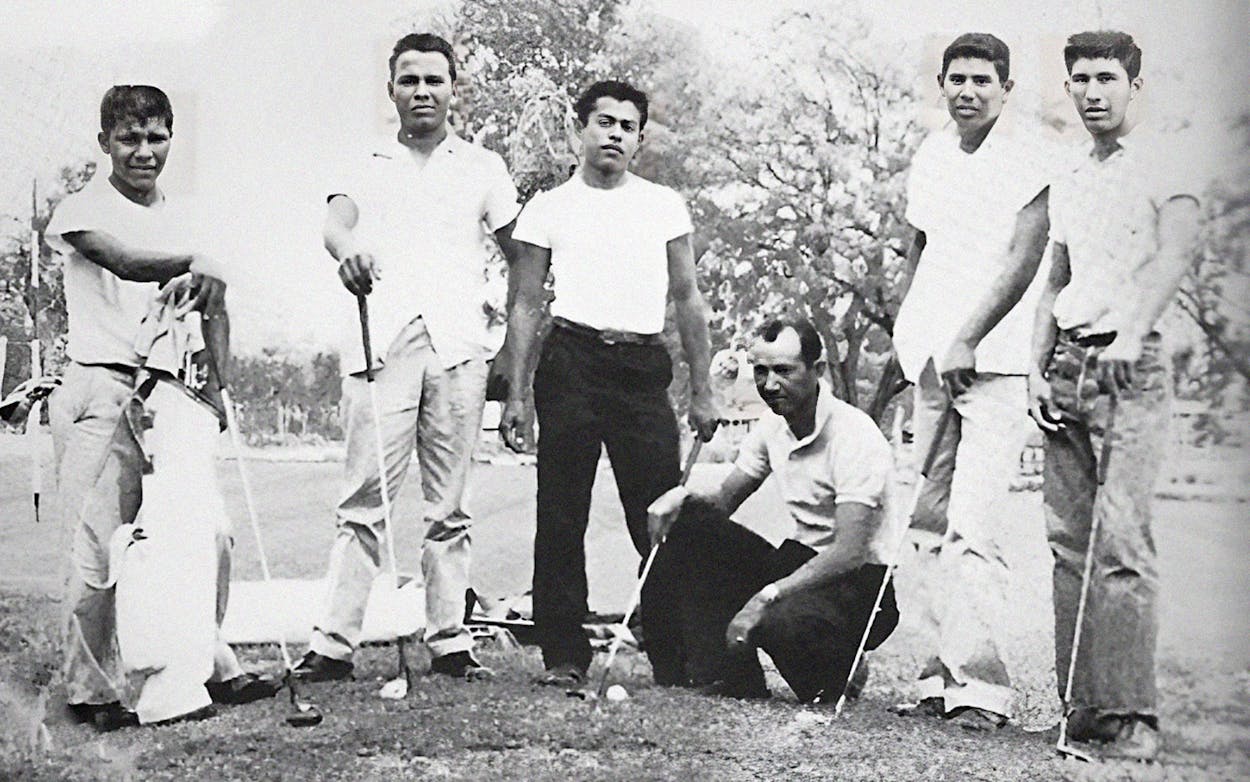

Not that the families of the five friends who created El Llanito could’ve afforded the membership fees anyway. Lupe Felan, Mario Lomas, Felipe Romero, Joe Trevino, and Higinio “Gene” Vasquez were poor Del Rio teenagers who attended segregated schools in the San Felipe Independent School District, the counterpart to Del Rio’s district for non-Hispanic whites. To earn a little money, the boys caddied at the country club, though they were barred from ever teeing it up there. So in 1954, they found an empty stretch of dirt on the llanito (Spanish for a small open plain) and made it their own.

El Llanito Country Club, the tongue-in-cheek moniker that the boys would give to their handiwork, was always more of a brotherhood than an actual golf club. In the physical sense, it wasn’t really a club at all. “It was just hard caliche,” remembers Felipe Romero, who is now 84 and lives outside Houston. “We would tee the ball up on the little grass stubs.”

The place started as a single makeshift golf hole the boys had bare-handedly scratched out of the hardscrabble earth, clearing cactus and mesquite and fashioning a crude fairway and a “green” that was actually brown most of the year. The hole did, however, feature three different teeing areas set at various yardages, which, in effect, made it three holes: a par 3, a par 4, and a par 5. Eventually, the boys expanded the course to a full nine holes that stretched for about a half mile. The five friends began spending a lot of time there. “We’d go often after school, probably three days a week at least,” Romero recalled.

The primitive condition of El Llanito matched that of the woods and irons the boys used. They were old, secondhand clubs that had been discarded at the country club where they caddied, and the boys all shared what little they had.

They didn’t even have a proper putter. But “I had a mashie with a hickory shaft,” Romero said. “And I also had what was known as a niblick, also with a hickory shaft. It was painted blue, and I bought it for seventy-five cents.” A mashie was the equivalent of today’s five-iron, and a niblick was akin to a modern nine-iron. One of the shafts was split, so Romero wrapped it in electrical tape to hold it together.

Despite these barriers, the boys from El Llanito achieved what at the time seemed impossible. In 1957, they won the Texas high school golf championship, beating out the teams in their division from wealthier and better-resourced districts all over the state. And then, as the decades reeled by, their story was largely lost to time.

That changed in 2008, when Humberto Garcia, a San Antonio attorney who grew up in Del Rio, competed in a golf tournament at the by-then-desegregated San Felipe Country Club. The event was part of the activities associated with a class reunion of former San Felipe students, and at the post-tournament awards ceremony, the emcee announced that he’d like to take a moment to introduce the members of the 1957 Mustang golf team—who’d won the state championship.

Garcia and his class of ’72 playing partners were slack-jawed. They had been under the impression that San Felipe High School had never had a golf team, let alone one that had earned a championship. “The light bulb went off: ‘I have to tell this story,’ ” Garcia said. Over the next four years, he interviewed the former players and dug through newspaper archives, though there was scant coverage of the event and no real stories noting its significance. The result was his 2012 book, Mustang Miracle.

Behind any great team is a great coach, and, as Garcia recounts in the book, that man was J. B. Peña, the superintendent of the San Felipe School District. He had heard about the five boys who golfed at El Llanito, and when he went to watch them play, he was impressed. Why shouldn’t San Felipe have a golf team?

Peña, who had an interest in golf himself but similarly suffered from limited access to the game, recruited Hiram Valdes, a like-minded friend who was a civil service aircraft mechanic at nearby Laughlin Air Force Base. The two would helm San Felipe’s maiden Mustangs golf team.

At the time, the University Interscholastic League classified Texas’s high schools into just three competitive divisions: B, 1A, and 2A. Today there are six. San Felipe was a 1A school that competed with other small schools, from towns such as Bandera, Eagle Pass, and Ranger. In 1956, the golf team’s inaugural year, the mighty Mustangs of San Felipe made a statement. They prevailed at the district and regional levels and made an appearance at the state championship tournament in Austin. Amazingly, they would finish in second place—just three strokes behind Ranger. The skills the boys had attained from playing El Llanito’s exceptionally harsh conditions had, it seemed, benefited them on the real golf courses they were now getting to play.

One theory credits Texas’s unpredictable and often-harsh climate as the reason the state has produced so many notable golf talents over the years—Ben Crenshaw, Sandra Haynie, Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Scottie Scheffler, Jordan Spieth, Lee Trevino, Kathy Whitworth, and Babe Didrikson Zaharias among them. Much of the state boasts a favorable environment for year-round play, which helps. But Texas golfers must learn to play in weather that is often windy and that ranges from cold and wet to hot and bone dry. They must learn to hit low shots and high ones, bouncing the ball up onto stone-hard greens or landing it next to the flag on damp ones. These factors seem to have helped set up the San Felipe golfers for success.

“When I think of the good Texas players through the years, I think of one word, and that is ‘hardscrabble,’ ” two-time Masters champion Ben Crenshaw has said. “It’s how we grew up as golfers. It’s how we dealt with the elements, and with adversity. And our games were stronger as a result.”

In this regard, El Llanito was a real proving ground. “Going from El Llanito to an actual golf course was like going from the desert to paradise,” Romero said. After the boys’ surprising on-course successes, some of San Felipe Country Club’s members took note and lobbied for the team to be able to practice on the club’s course—only on Mondays, when San Felipe was closed. The boys would be required to repair divots and ball marks—their own as well as those from the members’ play—and pick up any trash they encountered, but, yes, they could now take advantage of Del Rio’s one real golf course.

With additional practice on proper terrain, the 1957 Mustangs again prevailed at the district and regional levels, earning a return trip to Austin for the state championship. This time, despite enduring racist slurs from some of their competitors and adjusting on the final day of the tournament to a cold front and rain—which they didn’t see much of in Del Rio—the San Felipe Mustangs prevailed and won the 1957 state championship. They did so emphatically, besting runner-up Shamrock High School by a combined 35 strokes, taking the top three individual awards for the entire tournament. Joe Trevino was the top player, and Romero was the silver medalist.

Though the Mustangs received the trophies they’d earned, there was no awards ceremony in Austin for the all-Latino team, whose members wore jeans and white T-shirts as uniforms. Peña and Valdes, however, did make a stop in San Antonio, and the boys enjoyed a steak dinner, an infrequent treat. Back home, they would be lauded as the champions they had become.

And that was just about that. Gene, Joe, Mario, Felipe, and Lupe graduated and went their separate ways. Lupe Felan had a long career in the Marine Corps before going to work for the California Department of Motor Vehicles. He lives in Yucca Valley, California, and has continued to play golf. Mario Lomas, the bronze medal winner at the state championship, worked as a caddie on the PGA Tour before finding work as a greenkeeper at a country club in Abilene, where he continued to play. Felipe Romero played professional golf, attended the first National PGA Business School, in San Antonio, and then went to work for the Houston transit authority until retiring after 29 years. Joe Trevino, the Mustangs’ gold medalist, was highly recruited after graduating but stayed in Del Rio, where he worked in the maintenance division at Laughlin Air Force Base’s golf course. Trevino also worked at golf courses on military bases in California before retiring to Del Rio, where he was regular at area courses. Gene Vasquez earned a bachelor’s degree in education from Sul Ross State University and taught in the San Felipe public schools, later entering the real estate business in Del Rio. Vasquez also continued to enjoy the game of golf.

Without author Humberto Garcia’s efforts, their feat might have faded away completely, along with the course at El Llanito. Fortunately, it now appears that the boys of Del Rio will be introduced to an even larger audience. Garcia sold the rights to the story, and last spring The Long Game, a film directed by Austinite Julio Quintana (The Blue Miracle) and starring Jay Hernandez, Jaina Lee Ortiz, Dennis Quaid, and Julian Works, debuted at the South by Southwest Film & TV Festival. The movie won the festival’s Narrative Spotlight Audience Award, and it will be released in theaters nationwide on April 12.

Felipe Romero and Gene Vasquez attended the debut screening in Austin, as did Humberto Garcia. Joe Trevino passed away in 2014, and, sadly, Vasquez died a few months after the film’s premiere. Today, Romero and Lupe Felan, who lives in California, still keep in touch, though they’ve lost contact with former teammate Lomas. Romero tells me that he still swings a club now and then, but he doesn’t play anymore because of physical limitations. Felan reportedly does still play.

Upon seeing the film on the big screen with Romero and Vasquez in attendance, Garcia was elated. “It was an overwhelming rush of emotion. It was somewhat surreal,” he said. “I felt like I had fulfilled a promise I made to my boys to tell their story.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Sports

- Golf

- Del Rio