The video begins with a wide shot of family and friends eating and laughing, all of them gathered around a group of musicians with fiddles and guitars playing folk tunes. The camera gradually zooms in on a teenage boy standing in the back of the room. He’s smiling and swaying beside his mom, a middle-aged woman with short brown hair. He waves to his aunt, who’s filming the scene on a camcorder, and a minute later, she tells him, “Twenty years from now, you can come back and look at this.”

This was 1988, and Shane Stewart was sixteen years old. He wears a tight white button-down shirt with short sleeves that reveal his lean, muscular arms. His hair is bleached blond, shorter on top and longer down the back, just like Kiefer Sutherland’s character in The Lost Boys. Shane is laughing, acting goofy for the camera.

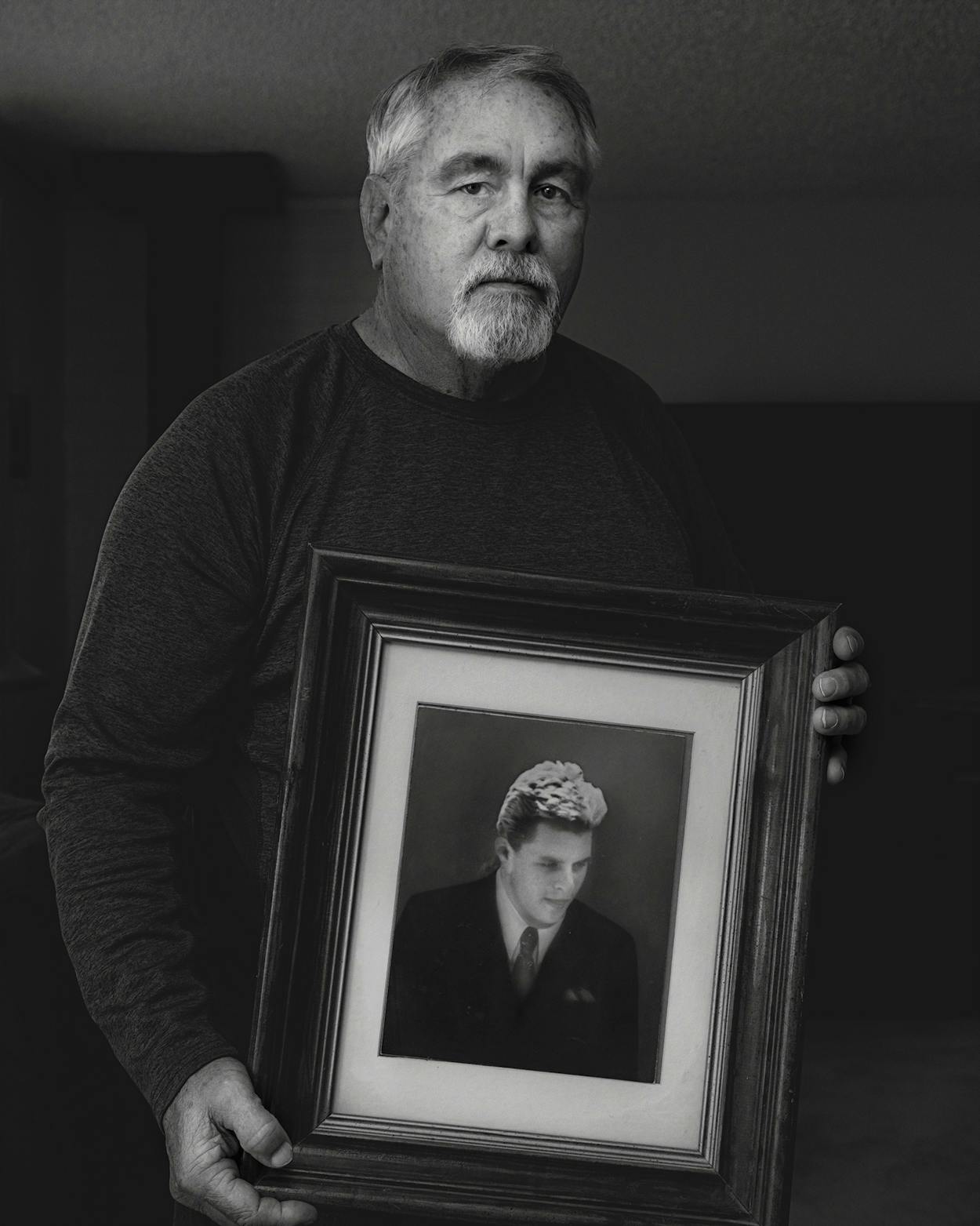

The boy’s father, Marshall Stewart, who is now 76, has watched these scenes more times than he can count over the past 35 years. One afternoon last summer, he sat at the kitchen table in his San Angelo home and stared intently as the footage unfolded on his laptop. His neatly combed hair and bushy mustache have gone gray, but his face looks ruddy and impressively unwrinkled. It’s the only recording he has of his son, the only way he can hear Shane’s voice. Marshall’s eyes still well with tears when he talks about him, how he was a fun-loving kid just trying to find his way in life.

On-screen, Shane’s aunt continues: “Yeah, you’ll have to come up and see it on my television.”

“That’s what I’m going to do,” Shane tells her. “I’m going to bring my kids, maybe.”

For months, Shane had been romantically involved with a girl named Sally McNelly. Outgoing, with feathered brown hair and big brown eyes, she was fifteen months older than Shane and had gone to school with him at San Angelo’s Central High School. Sally had dropped out, but she got her GED and had plans to join the Navy.

Marshall noticed that over the course of the teens’ relationship, Shane began to change. He started to dress in all black and seemed more distant.

“It was later that I found out that they became boyfriend [and] girlfriend,” Marshall recalled. “And I go, ‘Here we go. Now we’re going to get into those kind of relationships.’ ”

They separated once, when Sally left town to briefly work for a chemical company in Lubbock in the spring of 1988 and Shane took off to Kansas for a construction gig with his older brother, Sean. Despite the distance, Shane kept writing in his journal about Sally, and months later, when he returned to San Angelo, Sally was already back home. The couple reunited a few days before the Fourth of July, 1988.

The afternoon of the Fourth, Shane told Marshall that he was heading out to watch the fireworks with his girlfriend. Marshall told his son not to stay out too late and said that he loved him. Shane’s last words before leaving home were “I love you too, Dad.”

That evening Shane picked Sally up in his burnt orange Camaro, and the two set out for the city’s annual fireworks display at Lake Nasworthy. A handful of fellow attendees saw the teens there, parked among hundreds of other vehicles to gaze at the dazzling rockets and blooming booms. After the show, they drove off into the night.

Shane had promised to be home by 11 p.m., so when the clock struck midnight and he still wasn’t back, Marshall became worried. He jumped in his pickup with Sean and began scouring the neighborhood. They drove past houses where they knew Shane had hung out in the past, hoping they’d spot his Camaro, but they saw no sign of him. “It began to hit in your heart and in your gut—your stomach—that this is not right,” Marshall said. “Something’s wrong. Something’s wrong.”

After driving for about an hour and finding no sign of Shane or his car, they went home. The next morning a park ranger found Shane’s Camaro abandoned at O.C. Fisher Lake, a reservoir northwest of town. The car was parked by a picnic table, with the driver’s-side door wide open and the keys on the dashboard. The ranger ran the plates and spotted Marshall’s name on the title along with Shane’s, so he called Marshall to ask about the vehicle. Marshall and Sean rushed to the scene, where the ranger and a Tom Green County sheriff’s deputy were waiting. Marshall told them that Shane hadn’t come home the previous night, but the officers didn’t seem to share his concern.

“There wasn’t any evidence [tape] around,” Marshall recalled. “So I asked the detectives and the lake ranger, ‘Don’t be walking around the car. Let’s start looking for footprints. Let’s look for some kind of evidence that there might have been a problem, a fight.’ ”

More investigators arrived, but they found no signs of struggle in the vehicle and surmised that the teens had run off together, maybe to get married. Marshall couldn’t believe it. His son loved that car; he’d never willingly leave it with the keys on the dash and the door open. And if Shane and Sally had been intent on eloping, why would they ditch the car and walk several miles back to town? “I keep insisting that Shane did not walk off and leave his car,” Marshall said of that day. “We need to start looking. Search this area and see what we can find. Anything that will lead us to why did they leave this area, or how did they leave this area? . . . They kept going, ‘No, we think they just walked away.’ ”

The officers, Marshall said, rebuffed his suggestion to preserve some large tire tracks he spotted near the Camaro. Instead, investigators told Marshall to take the car home. Marshall climbed into the driver’s seat, filled with worry that his hands on the wheel could be contaminating a crime scene. When he got back to his house, he looked through the car and noticed a receipt, which showed that the couple had bought food from Whataburger the night before at 11:40 p.m. A day or two later, deputies had Marshall bring the vehicle to the sheriff’s office for a search, but by then evidence could have been lost or tainted. The episode cemented Marshall’s fear that local law enforcement wasn’t equipped to find Shane and Sally.

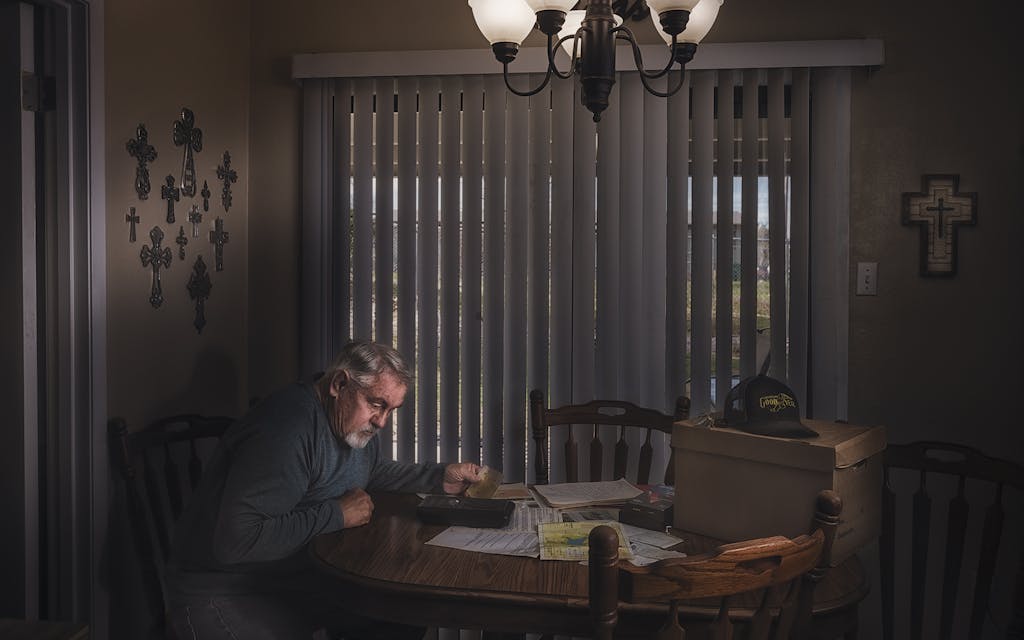

On July 5 Marshall began his own search for the missing teens. Throughout the rest of that long, sweltering summer and stretching into the fall of 1988, he paced the parkland surrounding O.C. Fisher Lake, combing the brush, searching for clues. “Just going through in my mind what could have happened, why it would have happened, how it could have happened.”

He also spent time trying to piece together a timeline of everywhere Shane and Sally had gone the night they vanished. Along with his son Sean and sometimes a brother-in-law who had worked in law enforcement, Marshall started knocking on doors to ask the missing teens’ friends what they knew about the couple’s whereabouts. One of his first visits was to a former schoolmate of Shane’s named Steve Schafer. Shane had told his older brother that he and Schafer didn’t get along, and Sean mentioned this to Marshall. “Shane said if they ever got together, there was gonna be a fight,” Marshall recalled. So when Schafer answered the door and had what looked like the beginnings of a black eye, Marshall became suspicious. Shafer denied having been in any fights and said he hadn’t seen Shane.

Meanwhile, the official search for Shane and Sally remained in the hands of the Tom Green County Sheriff’s Office. Marshall pleaded with deputies to share details of their investigation, but they mostly kept him at arm’s length, so he bought a police scanner to track their progress as best he could. Sally’s mother and stepfather, Pat and Bill Wade, were also frustrated with the scant communication from authorities. Like Marshall, Pat criticized the investigators’ decision to send Marshall home in the Camaro that first day. “It’s ridiculous,” she said. “Common sense tells you that you don’t do things like that and you preserve the crime scene. I know that, and I have absolutely no law enforcement background.”

“I’m not turning around, and I’m not going to leave,” Marshall told the officers. “They found my son down there, and I’m going to see my son.”

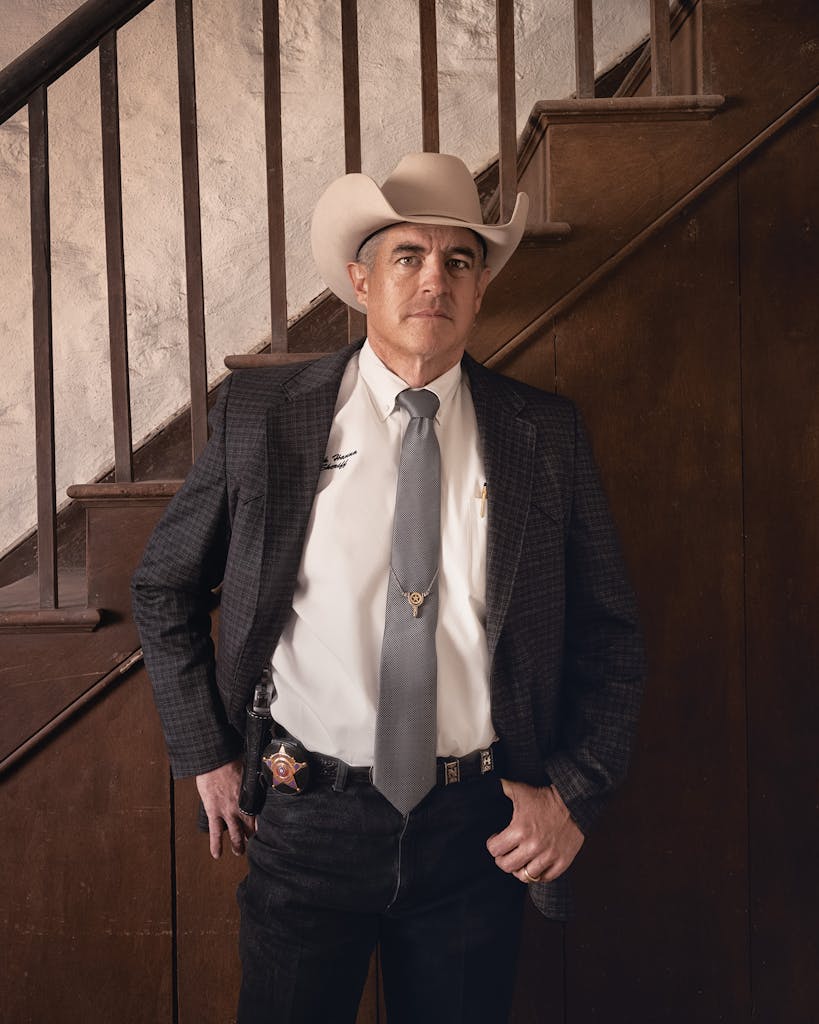

Nick Hanna, who was elected Tom Green County sheriff in 2020, agreed that his predecessors’ initial investigation left much to be desired. “They had [Marshall] drive the vehicle from the scene to the sheriff’s office for processing, a practice that today would be abhorrent,” Hanna said. “In 1988, I guess I would say maybe it was just against best practices—you would never have someone drive [their] vehicle down to be processed.”

Ernest Haynes, who was sheriff at the time Shane and Sally went missing, died in 2002. One of the deputies who worked for the sheriff’s office in the late eighties, Christopher Cherry, said the agency suffered from a lack of resources back then. “I can tell you that the three investigators at the Tom Green County Sheriff’s department at that time were straight arrows— honest, compassionate, very good men,” said Cherry. But, he added, “when I went to work—[to] show you how bad it [was]—I got two or three pairs of trousers, two or three shirts, and a car. I bought my gun belt, I bought my handcuffs, my handcuff carriers, I bought my own ammunition.”

Sheriff’s reports from the summer of 1988 show that deputies were conducting their own interviews about Shane and Sally’s disappearance, and as days grew to months, and the supposed teen newlyweds never returned, investigators began to suspect foul play.

Four months passed. It was the afternoon of November 12, and a deputy had been dispatched to the south pool of Twin Buttes Reservoir, on the far southwest outskirts of San Angelo. Marshall happened to be listening when the deputy’s muffled voice came over the scanner: a hunter had found a body in the area.

Marshall feared it was one of the kids. He called the sheriff’s office to ask about the body, but the deputy he spoke to wouldn’t confirm who it was and asked him to stay away from the scene. Marshall didn’t know it yet, but investigators believed they’d found Sally. The skeletal remains were still dressed in clothes that matched descriptions of the outfit Sally had worn on the Fourth.

But they didn’t find Shane. Meanwhile, Marshall waited in agony, thinking that an official notification about his son’s fate could come at any time. Sally’s remains were taken to the medical examiner in San Antonio, who noted that some teeth were missing. The examiner asked deputies to return to Twin Buttes to look for them. Two days later, when they searched the scene again, deputies discovered Shane’s body covered in brush, 75 feet away from where Sally had been found.

When Marshall’s scanner relayed news of another body found at Twin Buttes, he rushed to the reservoir. “There were detectives and DPS [Texas Department of Public Safety] officers and justices of the peace out there,” he said. “They stopped me a block or so away from the site, and they said, ‘You need to turn around and leave.’ ”

“I’m not turning around, and I’m not going to leave,” Marshall told the officers. “They found my son down there, and I’m going to see my son.”

“Well, it’s not going to be pretty,” one told him.

“It hasn’t been pretty since they disappeared,” Marshall answered, “but I told my son I’d find him.”

He knelt beside Shane’s body, which was dressed exactly like he had been when he left the house. “Two kids murdered for no reason at all,” Marshall recalled. “Laid out like animals.”

The medical examiner determined that the teens had been killed by shotgun blasts fired at close range. The grieving families held a joint funeral for Shane and Sally, and the teens’ bodies were buried side by side in a San Angelo cemetery. Shane died a month shy of his seventeenth birthday. Sally was eighteen, laid to rest with her prom dress folded inside her casket.

More than 35 years after Shane and Sally were murdered, no one is behind bars for the crime. The case is still open—and sheriff’s investigators have suspects and a mountain of paper reports—but it has been officially declared cold. Marshall has spent nearly all of those years—and almost his entire life—in San Angelo, but he doesn’t have particularly kind words for his city. “It’s been a very wicked town,” he said. “Always has been.”

San Angelo lies 75 miles west of the geographical center of Texas, and the city has long served as a gateway to West Texas. It took shape in the late 1860s around the establishment of Fort Concho, an outpost built to protect settlers who moved to the area after the Civil War. At around the same time, with the arrival of the railroad, San Angelo’s population swelled with folks hoping to find their fortune—or at least make a living. Ranchers began carving up the land surrounding the city, and the cattle industry took off. San Angelo Junior College—now Angelo State University—was founded in 1928.

For much of its history, San Angelo was best known for its sheep. The city has proclaimed itself the Wool and Mohair Capital of the World, with an industry that once produced more than one million pounds of wool per year. In 2022 output for the county was down to about 82,000 pounds, but the city still celebrates that heritage with larger-than-life fiberglass sheep sculptures along its sidewalks.

Marshall’s father drove a truck to transport livestock for much of his life, and even though he once swore to never follow in those footsteps, Marshall took to driving sheep and cattle too. “We call them bull wagons, double-deckers hauling calves,” he said. “Ours was a little bit taller than that, because we had room for three decks of sheep. And then I’d haul feed in the winter out to the ranches. . . .I would go as far as Del Rio, within a two-hundred-and-fifty-mile radius of San Angelo.”

The job meant getting up at four in the morning and returning at around five in the evening, but Marshall said it suited him: “I like sheep. I never had a problem hauling livestock. And even the ranchers would go, ‘There’s only one person we’ve ever had out here that could handle stock the way you can.’ And I’d say, ‘Oh yeah, who’s that?’ They would start describing him. I’d say, ‘That’s my dad.’ ”

Shortly after he started driving, in 1967, Marshall married his childhood sweetheart, Gail, a girl from the same neighborhood, whose family attended the same church as Marshall’s. Within a year their son Sean was born. About three and a half years later they had a second son, Shane.

Marshall’s experience behind the wheel helped him get a new job as a test driver at Goodyear’s proving grounds in San Angelo. For almost forty years, Marshall pushed tires to the limit with extreme braking, turning, and acceleration, to make sure they were ready for market. Hauling sheep may have suited him just fine, but the new position offered better pay and health insurance for Gail and their two boys.

For several years, life seemed almost idyllic, until Marshall and Gail’s marriage began to crumble. They eventually divorced, and Gail moved to Dallas in 1986. (Caroline Gail Stewart died in March 2023.) When Sean left for college that fall, it was just Marshall and Shane. Even when sixteen-year-old Shane became a little more withdrawn and started wearing black and styling his hair in a blond mullet, Marshall adored his spirited younger son.

The Podcast

Follow along as reporters Rob D’Amico and Karen Jacobs host Shane and Sally, a podcast investigating the murders of Shane Stewart and Sally McNelly, available at TexasMonthly.com/shaneandsally and on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and elsewhere.

Watch the trailer for the Shane & Sally podcast.

Last summer Marshall offered to show me around the parts of San Angelo where he spent years searching for clues that might aid his investigation. I hopped in the back of his blue Ford pickup, and with Marshall behind the wheel and Sean, who’s 56 now, riding shotgun, we headed to O.C. Fisher Lake. When we arrived, Marshall and Sean looked past the rolling hills and patches of mesquite trees and scanned a long row of concrete picnic tables lining the road, searching for the exact spot where the empty Camaro had been recovered.

Marshall pulled off the road. “I think it’s this one,” he said, climbing out of the pickup and standing beside the picnic table. He took in the surroundings, noting the ways the lakeside park had changed and what he remembered from that summer of 1988. “This was dirt,” he said of the paved route we drove in on. “The road was dirt and there were tracks out there.” He was reminded of the investigators whose first instincts told them that Shane and Sally had run away. “I kept telling them to stay off of the tracks,” Marshall said. “‘You need to make a cast of these tracks’” he told them, because “we can tell what kind of tire it was.”

After the bodies were discovered, investigators reasoned that there had been more than one killer, because it would have been nearly impossible for a lone assailant to subdue both Shane and Sally without a struggle, then drive them fifteen miles from O.C. Fisher Lake to Twin Buttes Reservoir. Marshall and Sean agreed with the theory that the two weren’t killed where the Camaro was found. “There weren’t any signs of, you know, blood, bullet casings, torn clothes on the car, in the car, around the car, anything around there,” Sean said. “But it’s horrifying to think that they endured some kind of torture trip, like bound up and abducted and then killed later.”

We soon pulled out and drove toward the outskirts of San Angelo, eventually turning onto a deeply rutted dirt path heading to Twin Buttes Reservoir. “This road’s always been like this,” Marshall said. “It’s never been a smooth, flat, get-in-and-out road. So if you want to come in here, you gotta want to come in here. And because of the location of the bodies, whoever came in here knew this road. ’Cause you can break an axle. You can run off a cliff, you can have all kinds of mechanical problems, and you’re gonna have to walk out.”

A recent rain had left a stretch of muddy puddles that made the road impassable beyond a certain point, but Marshall had gotten us close enough to where the bodies were found, and the landscape was all the same—thorny mesquites covered the fields, creating a maze for anyone trying to bushwhack through on foot. He wondered aloud why the killers picked this spot, which, although remote, still attracted hunters. Why hadn’t the killers gone farther into the brush or worked harder to conceal the bodies? “For thirty-five f—ing years,” Sean said, “my brain’s been turning over all these questions.”

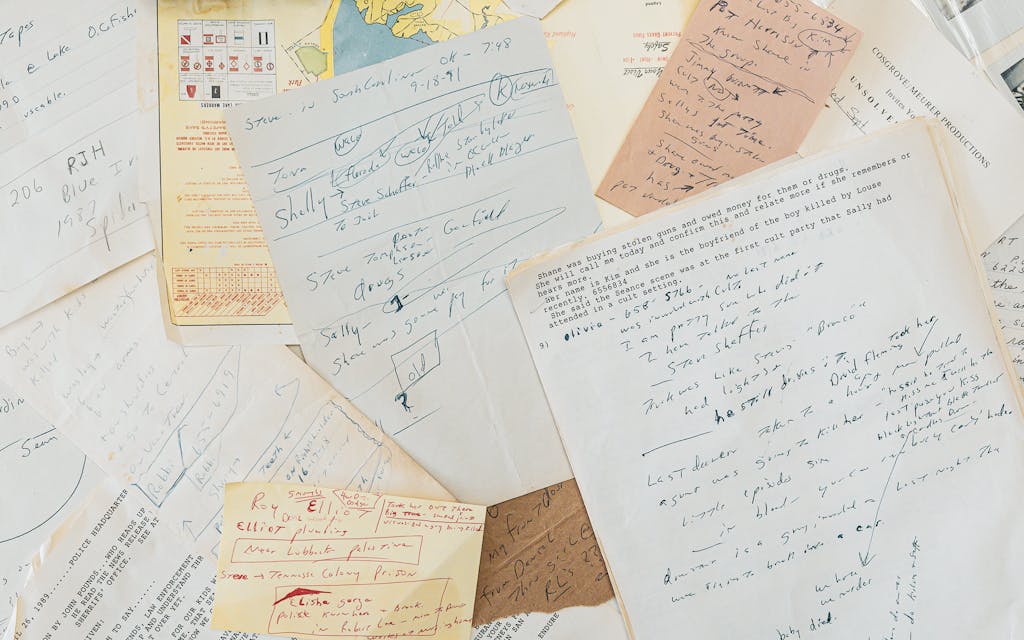

After the missing persons case became a murder probe, Haynes, the Tom Green County sheriff, assigned two detectives to the case and enlisted the help of criminal-investigations officers at the Department of Public Safety and, later on, the Texas Rangers. By the end of December 1988, law enforcement had interviewed 25 potential witnesses, mostly teens associated with Shane and Sally. That effort produced several leads, but those conversations seemed to amount to little more than a tangled web of rumors. Conflicting accounts piled up, with no clear way for law enforcement to suss out the truth.

Marshall had already tracked down and spoken with many of the same sources during the months he spent searching for Shane and Sally. He’d talked with Jimmy Burnett, who investigators were told had dated Sally before Shane came home from Kansas.

An early theory—one that investigators took seriously, despite how it sounds today—was that Sally had become involved with a satanic cult, that she wanted out, and that the cult members killed her in retaliation. This narrative was broadly supported by a witness named Randall Littlefield, who came forward in early 1989. Littlefield told officers he and a friend had been fishing on O.C. Fisher Lake on the night of July 4, and, while they were checking trotlines, he saw Shane and Sally leaning against the Camaro when a pickup truck pulled up and shone its lights on them. The truck had “KC lights,” a row of bulbs on a roll bar atop the cab. Littlefield said he watched two young men exit the truck and begin arguing with Shane and Sally. He couldn’t hear much, but he said he could make out Sally yelling at them. “No, she would not do it again,” Littlefield recalled Sally saying. He said he heard her tell the men “that she was leaving ’em, that she would not have nothing to do with ’em.” Then the truck backed up and left.

Could that have been an encounter with cult members? The late eighties marked the height of the “satanic panic” that swept across the U.S., when crimes ranging from sexual assault to murder were attributed to devil-worshipping cabals. Thousands of Americans faced false accusations for crimes linked to satanic cults, and dozens went to prison for those offenses. The Innocence Project of Texas is still working to exonerate individuals who were wrongly convicted during the mass hysteria that peaked more than thirty years ago.

Case files are rife with secondhand tales of animal sacrifices, attempts to summon vampires and talk to the dead, and sites out by the lakes where the cults supposedly performed late-night rituals.

But in late-eighties San Angelo, the fear of satanic cults was genuine and widespread. At the time, Shane’s love of heavy metal and Sally’s penchant for Ouija board sessions could have been seen as signs that they might also belong to a cult. Today old friends call the cult implications overblown. “I totally believe she was doing that just to entertain herself,” said Michael Heath, a friend of Sally’s who also knew Shane. “She would laugh about things like that.”

Regardless, investigators homed in on a theory that someone in the supposed cult was unhappy with Shane and Sally because they had decided

to leave the group. The law enforcement case files are rife with secondhand tales of animal sacrifices, attempts to summon vampires and talk to the dead, and sites out by the lakes where the cults supposedly performed late-night rituals. Deputies interviewed sources who described Steve Schafer, whom Marshall had seen with a bruised eye shortly after Shane and Sally disappeared, as a cult leader known for wearing leather straps around his neck with a sawed-off shotgun attached. One source described him as the “high priest” of a San Angelo cult. (Schafer denied having any connection to the occult. He told Texas Monthly that he and his friends used to scuffle with kids who performed rituals around town. “We’d sneak down there and surprise them and beat them up,” he said. “So yeah, we didn’t get the chance to join the cult.”)

Marshall kept conducting his own interviews. “I realized through [Shane and Sally’s] friends that there was a cult,” he said. “They had been involved in it, were trying to get away from it.” Even when confronted with seemingly far-fetched stories of bestiality, upside-down crosses showing up in families’ yards, and a rumor that Sally had been ordered to kidnap a six-month-old baby for use in ritual services, Marshall felt he couldn’t ignore the possibility of cult involvement. If law enforcement pursued the theory, why shouldn’t he?

Marshall learned as much as he could about satanists, purchasing a copy of Necronomicon, a fictional book containing black magic spells, and the 1988 true-crime title Cults That Kill, which purported to document a ghastly wave of occult crimes sweeping the nation. During our ride to Twin Buttes, Marshall recalled bringing a video camera to the lakes to document pentagrams and other unusual vandalism spray-painted on picnic benches. He said he began patrolling the lakeside areas where teens liked to hang out at night, aiming to disrupt possible cult activity—even though the youths he encountered were mostly engaged in less sinister behavior.

He was looking for anything that might lead to information about Shane’s killers, but he also hoped to save innocent teens by scaring them away from the area. When he saw cars by the lakes late at night, Marshall would simply park nearby and stare at them. “They would get real nervous, and they would look at me for a little bit, and then they would start their cars and leave.”

On a couple of occasions he cornered the same pickup truck out there in the dark. The way the driver sped away from each encounter struck Marshall as suspicious, so one night he followed it. Suddenly, he said, he found himself chasing the pickup at speeds of up to 100 miles per hour. The truck led him to Twin Buttes Reservoir—right back toward the spot where Shane’s and Sally’s bodies had been dumped. “In my mind I said, ‘This is a trap,’ ” Marshall recalled. “He’s fixing to go up here and turn around and confront me. And I stopped. I didn’t have a phone. I didn’t have a weapon with me. I said, ‘This is as far as I go.’ ”

Over time,the satanic panic subsided, and the nationwide hysteria turned out to be, for so many falsely accused Americans, catastrophically exaggerated. Marshall backed off of his cult studies. Hanna, the Tom Green County sheriff, first looked into the Shane and Sally murders in 2009, when he was in the Texas Rangers. He retraced old leads related to cult activity, but these days he largely discounts those theories. “When you look at it, it usually comes to the same motivations,” Hanna said. “Drugs, money, sex.”

Five months after the teens’ bodies were found, Marshall and Sally’s parents were willing to try anything to bring the killers to justice. In April 1989 they held a press conference asking the public for help, with a $5,000 reward offered to anyone who provided tips that led to an arrest. The event drew local news coverage, including from the San Angelo Standard-Times, which followed up a month later by highlighting the case in its “Crime Stoppers” column.

These appeals failed to generate much useful information. Two years passed, and Marshall began to wonder if the case would ever be cracked. Then in 1991 a producer from Unsolved Mysteries called him. The makers of the hit series were interested in featuring Shane and Sally’s story in their season-four premiere later that year. Marshall had never seen the show, known for its sensationalized crime reenactments and requests to the audience for tips, but he thought it might help find Shane’s killers, so he agreed to participate. Sally’s family and the Tom Green County Sheriff’s Department also cooperated with the show and looked forward to any help it might provide.

Marshall recalled the producer being particularly interested in the satanic-cult angle. “I really didn’t want to hang my [hat] on any one thing,” he said, “but I mean, that’s the most prominent thing to get a story put together, and I wasn’t going to tell him no.” At the time, Unsolved Mysteries was one of NBC’s top-rated shows and among the most-watched programs in the country.

In its early years, Unsolved Mysteries sometimes used real-life friends, family, and witnesses as amateur actors in its reimagined crime scenes. That put Marshall and Sally’s mom, Pat Wade, in the uncanny position of playing themselves in a fictionalized reenactment of the final days of their kids’ lives. Marshall said he tried to be professional, but the young actor playing Shane bore such an eerie resemblance to his son—with broad shoulders, a spiky blond mullet, and a wide smile that looked just like Shane’s—that Marshall struggled to keep his grief in check during the shoot. “I tell you what—that boy, it just created anxiety in me because he was so much like Shane,” Marshall recalled. “It was very emotional.”

The episode, which aired September 18, 1991, opens with Unsolved Mysteries’ trademark piano theme, accompanied by the gruff, monotone voiceover of host Robert Stack, who introduces the Shane and Sally segment about halfway through: “Next, the murder of two teenage sweethearts. Some say they were victims of a bizarre cult.” After a few seconds of home video footage of Shane clowning around and kissing his bicep, Marshall appears on-screen. “To me he was like Beaver Cleaver,” he says, “the all-around boy.” Pat Wade tells the camera: “Sally tried hard to please people. She wanted people to like her. She wanted people to respond to her and love her.”

Two years passed, and Marshall began to wonder if the case would ever be cracked.

For its reenactment, the show used a Camaro just like Shane’s in the scene where authorities discover the abandoned vehicle the morning after the Fourth of July. Another scene shows Marshall’s encounter with Steve Schafer, who is portrayed by an actor. “Shane told me if he and his friend ever got together, there was going to be bad trouble,” Marshall recalls during the episode. “I walked away from the door convinced he had confronted Shane somewhere, and there had been a fight, and he just wasn’t telling me the truth.”

Midway through the segment, a reenactment reveals a detail that investigators hadn’t made public before the show aired and that Marshall hadn’t known about before filming the episode: Shane and Sally had been given a gun by someone in the supposed cult. And that person asked them to hide it because it had been used in a murder. Not knowing what to do, Sally called the sheriff’s department in March 1988 to turn it in. In reenactments, Deputy Larry Counts, also playing himself, is shown meeting with the teens to retrieve the firearm. Marshall recalled feeling stunned when he first learned about the gun. “I didn’t know that part of it,” he said. Only later would he learn the mysterious fate of that weapon.

For now, he struggled with seeing the story of his son’s murder being turned into pulp entertainment. “It’s hard to sit there and watch it—realize you’re reenacting something about your kids disappearing, and there’s no resolution,” he said. “And you’re just asking for somebody to call in and give an answer in anticipation that somebody might come forward.”

In the end, Unsolved Mysteries didn’t produce any case-breaking tips. “They got phone calls,” Marshall said, “but it didn’t sound to me like they received a lot of them. . . . And then we just went back to day-to-day.”

After the excitement from the TV show faded, Marshall and the Wades heard little from law enforcement. Hanna, the Tom Green County sheriff, said that’s likely because it was department policy not to reveal privileged information about an “active investigation”—even to the victims’ parents.

Being kept out of the loop frustrated Marshall, who continued patrolling San Angelo over the years and feeding what he learned to investigators. “I was trying to stay close to law enforcement,” he said. “But it was tense because I was excluded. And unless there was something significant, I wasn’t going to know about it.”

Meanwhile, the sheriff’s inquiry continued to focus on a handful of key suspects, including Schafer and Jimmy Burnett. According to case files, when deputies interviewed potential witnesses in the teens’ friend group, those two names kept popping up—Schafer as the supposed cult leader and Burnett as Sally’s volatile ex with cult ties of his own. Both Schafer and Burnett drove trucks with KC lights, similar to the vehicle Littlefield saw at O.C. Fisher Lake on the night Shane and Sally went missing. Deputies questioned Schafer and Burnett multiple times, and both agreed to undergo polygraph tests, but neither was charged.

Investigators’ notes told of another major suspect—John Gilbreath, a peer of Shane and Sally’s who had contacted Marshall and the Wades to offer his help after the teens’ bodies were found. According to the case files, however, at around that same time Gilbreath was also bragging to others about details of the crime that weren’t public knowledge. One of the investigators’ sources said that Gilbreath had brought her and a friend to the lake to point out where the victims were attacked and demonstrated how they would have been murdered with a shotgun. Investigators would later say that Gilbreath appeared to be trying to insert himself into the case, and that although he might have gleaned privileged information from deputies who revealed too much while interviewing him, his stories about the murders didn’t always match evidence at the scene.

In fact, according to Hanna, the early investigators considered most of the sources they spoke with to be unreliable—some used drugs, some already had criminal records, and some gave conflicting accounts regarding key suspects’ alibis. “You’ve got to have a case that satisfies a prosecutor,” Hanna said. “There may be a statement that says ‘so-and-so did it, and I was there and saw it.’ But if your witness is giving two or three different statements, what good are they? And there’s no corroborating evidence.” By the time Hanna took up the case, he said it was mired in dubious statements from shaky witnesses. Meanwhile, physical evidence that might have been used to identify the murderers was likely contaminated the day sheriff’s deputies instructed Marshall to drive his son’s Camaro home from the original crime scene.

The one promising piece of evidence in the case, it seemed, might be the gun. If Shane and Sally had turned over a weapon they’d heard was used in a murder to law enforcement, then whoever gave them the firearm could have been a key witness. But investigators never got the chance to follow that lead. After sheriff’s deputy Larry Counts picked up the weapon from Shane and Sally, case files show he was able to trace it to a San Angelo military-surplus store that had reported it stolen in 1984. Because Shane and Sally told Counts the gun might be linked to a crime, he turned it over to the San Angelo Police Department to see if the weapon could be traced to any open cases. Sometime after that, the gun disappeared.

Today San Angelo police don’t even have a record of receiving the gun. More than twenty officers who worked at the department at the time have said they had no idea a gun related to the Shane and Sally murders had been turned over to their care. Several officers admitted there should have been a report on the gun, or at least forms that show it was accepted as evidence, but the department has no such records today. The Tom Green County sheriff has declined to release Counts’s full report on the incident from 1988, but the department did share one paragraph in which Counts describes turning over the weapon to a San Angelo police officer, Larry Massey. When contacted last fall, Massey said he doesn’t remember receiving the gun. Counts said, “There should have been a paper trail of the property evidence that would’ve had the make and the model and the color and the serial number and all that stuff on it.” The police department could not provide any such record.

For Marshall, this bit of botched police work is the most infuriating blunder of all. Sally got a gun, she handed it over to police, and four months later she and Shane went missing. That gun might have represented Marshall’s best chance at knowing who killed his son. And the gun is gone.

For almost thirty years, Marshall and the Wades carried the memories of their kids’ disappearances. New sheriffs took office and left, Texas Rangers arrived in San Angelo to take a crack at the case, and still, the investigation never seemed to budge.

Then in June 2017, there came a break. A deputy in San Angelo pulled over John Gilbreath, the man who had boasted of knowing how Shane and Sally had been killed, for not using his turn signal. When Gilbreath rolled down his window, the deputy smelled marijuana in the car; he searched the vehicle and spotted a couple of joints in the door. In the trunk he found a half-pound of weed, a Kevlar vest, and a handgun. Gilbreath had a previous felony conviction, which prohibited him from owning a handgun, so he was sent to jail. A woman who’d been riding with him, fearing she’d do time for the drugs, told investigators Gilbreath had more evidence of drug distribution at his house.

When Hanna heard what had happened, he jumped at the opportunity to inspect the home of one of the prime Shane and Sally suspects. When deputies searched Gilbreath’s apartment, in addition to further evidence of drug dealing, they found notes he’d written about the Shane and Sally case, an audiocassette marked “SS,” some hair, fingernails, and “biological material” that might have been blood.

Headlines From as far away as New York and London screamed of a new development in the decades-old murder, alongside a mug shot of a gaunt, gray-haired Gilbreath.

“As an investigator,” Hanna recalled, “I was pretty excited about that.” He didn’t intend to let the media get wind of the search before investigators could determine if DNA from the hair, fingernails, or biological material matched samples the department had for Shane and Sally. But a reporter for the Standard-Times managed to get the story, and headlines from as far away as New York and London screamed of a new development in the decades-old murders, alongside a mug shot of a gaunt, gray-haired Gilbreath staring into the camera with piercing eyes.

The DNA from the items in Gilbreath’s home didn’t match that of the victims, though. Gilbreath served a little over two years for the gun violation, but authorities couldn’t pin the Shane and Sally murders on him. Gilbreath’s handwritten notes about the case and the tape marked “SS” were suspicious, but investigators said they couldn’t make a case against him without physical evidence. None of the media outlets that ran stories about Gilbreath’s 2017 arrest bothered to follow up with reports that DNA evidence failed to prove he had been one of the killers.

Nowadays, if you ask San Angelo residents about the Shane and Sally case, many will ask, “Didn’t they get that guy?” They didn’t. Whatever closure Marshall and the Wades were seeking, it wasn’t coming.

Marshall still lives in San Angelo and today works for a subsidiary of Goodyear, although he’s moved from the testing grounds to a desk job at the company’s credit union. In the years after Shane’s death, he formed a support group for individuals whose loved ones had been hurt or killed in violent crimes. “There were probably about fifteen different families that came through,” he said. “We basically just let the group talk through where they were in the process. Are you at the angry stage? Are you at the forgiveness stage? Are you just overwhelmed? Some of the people made progress. Some left as angry as when they first started.

“I think it helped me to see everybody else going through things that I was going through,” he went on. “But some of them had come to a conclusion, like I had, that it’s going to continue. I’m going to have to learn to deal with this.”

At one of those meetings, he met a woman named Brenda. She joined the group in 1991, after her husband was stabbed to death in a store robbery. Over time, she and Marshall grew close. They married in 1996 and have been together ever since.

Across the country, survivors like Marshall and Pat and Bill Wade rely on one another to deal with an anguish only they can understand. Another, larger group, the National Organization of Parents of Murdered Children, counts thousands of members from coast to coast, with 45 chapters active in 23 states and dozens more official “contact persons” serving areas without enough individual members to sustain monthly meetings.

This community is why Marshall still agrees to interview requests when TV news stations and local papers put together anniversary stories about Shane’s and Sally’s unsolved murders. The chance to share his grief and to preserve his slain son’s memory—are the reasons he still tells his story in magazine articles and true-crime podcasts. He does so even though the reminders of Shane’s fate torment him as much today as they did in the first few years after the crime. “It’s like, bang, there it is, in your face,” he said. “We have to keep living through it.”

Marshall hasn’t lost hope that Shane’s killers will be caught. The Texas attorney general’s office formed a Cold Case and Missing Persons Unit in 2021, and at the urging of Marshall and the Wades, Hanna asked the group to review the Shane and Sally investigation. The AG’s unit declined to reveal specifics for this story, but said, “The case is under review.”

Nowadays, if you ask San Angelo residents about the Shane and Sally case, many will ask, “Didn’t they get that guy?” They didn’t.

Marshall still bristles at that—when investigators keep him in the dark about anything related to Shane and Sally. Recently he learned that John Gilbreath, after he was released from prison, wound up living in a house kitty-corner from his home. Marshall was livid that no one in law enforcement saw fit to let him know that a suspect in his son’s killing had moved in right down the block.

Standing in his kitchen, Marshall looked down and rubbed his key chain, a gold medallion engraved with the words “Dad’s Keys.” It was the last Christmas gift his son gave him. “I don’t have a clue what kind of life Shane would’ve had,” he said. “I’m sure it denied me grandchildren.”

He considered this a bit further. “But then there could have been worse things that came along that he would have had to go through. And in a way, I’m glad that maybe it saved some pain in his life.”

Marshall, who’s outlived his son by almost 36 years, was spared no such suffering.

Rob D’Amico is an investigative journalist living in Far West Texas and the managing editor of the Big Bend Sentinel. He recently hosted the true-crime podcast Witnessed: Borderlands, for Campside Media.

This article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Who Killed My Son?” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Longreads

- San Angelo