She never felt right about sending him to prison. Every year around Christmas, Estella Ybarra would find herself thinking back to December 1990 and that El Paso courtroom, where for three days she sat on a jury holding Carlos Jaile’s fate in her hands. From the start of the trial she’d been unimpressed by the evidence that he had raped an eight-year-old girl. The state’s case hinged on the victim’s identification of Jaile in a police lineup two years after the attack. The girl said her assailant wore mechanic’s clothes and drove a beige sedan. Jaile was a successful vacuum cleaner salesman who wore a shirt and tie and drove a red Subaru hatchback. His lawyer brought in three alibi witnesses who testified he was with them that day. Ybarra was certain he wasn’t guilty.

Then she went to the jury room. Ybarra was 48 at the time, just four foot nine, with long black hair. She worked as a supervisor at Lighthouse for the Blind, an agency that helps the visually impaired. She was outgoing with friends and colleagues, but not as much with strangers. She had never served on a jury before, and the truth was the El Paso native had only recently started to feel comfortable speaking English.

When the jurors began deliberating around 2:30 p.m., she quickly realized that only a few others believed in Jaile’s innocence. She remembered two white men in particular, both of them loud and pushy. “He’s guilty,” each insisted the moment they entered the room. They kept referring to the most dramatic moment in the trial, when the victim took the stand and pointed out Jaile right there in the courtroom. In their minds, no further proof was needed. Their arguments got more emphatic as the afternoon wore on, with one of them eventually raising his voice in exasperation: “We shouldn’t be sitting here wasting the government’s money!” The other holdouts, all of them Mexican American women, gradually gave in.

Finally, sometime around 5 p.m. on December 19, Ybarra succumbed to the pressure too. Back inside the courtroom, she hung her head as the jury announced its verdict. Ybarra couldn’t bear to look at Jaile as he learned he was being sent to prison for the rest of his life.

It was cold and dark when she arrived that night at her little brick house on a cul-de-sac in a working-class neighborhood in El Paso’s Lower Valley. She expressed her doubts about the case to her husband, a former deputy sheriff, and her four grown sons. The trial was over, they told her. There wasn’t anything else to be done. She felt completely alone.

A few days later she got a letter in the mail. At the top, the word “Award” was printed in bold. “This certification of appreciation is given to Estella Ybarra for able service as a Juror in the 65th Judicial District Court,” it read. “By accepting this difficult and vital responsibility of citizenship in a fair and conscientious manner, you have aided in perpetuating the right of trial by jury, that palladium of civil liberty and the only safe guarantee for the life, liberty and property of the citizen.”

Ybarra snorted in disgust. “We sent an innocent man away for the rest of his life,” she thought to herself. She stuffed the certificate back in the envelope and tossed it in a desk drawer.

Her life went on. Years passed, then decades. Her four sons married and had children. She grew into her new role as an abuela. She stopped working, and her husband retired. Every year at Christmas she would sit around the tree with her children and grandchildren, opening presents and talking about their lives. She treasured such moments, but during those gatherings she also found herself wondering about Jaile: What was his Christmas like, locked in a lonely Texas prison cell? Did he have kids? What about his parents? The shame she felt came flooding back. Why hadn’t she stood her ground?

Then one day in 2017, she was cleaning out her desk drawers and came upon an old envelope. She opened it and, to her surprise, there was the juror’s certificate. Though it had been 27 years, her “award” was in pristine condition. She held it in her hands, studying those principled words that had unsettled her in the days after the trial: fair and conscientious, life, liberty. All of the old regrets rose in her again. But this time something shifted. For reasons she didn’t completely understand, she felt different.

This time, she decided to do something about it.

In the eighties, Carlos Jaile was one of the best vacuum cleaner salesmen in El Paso. He sold Kirbys, the elegant, retro machines with distinctive wide steel nozzles. Kirbys were expensive and sold only in person, inside the homes of potential customers, a dynamic in which Carlos thrived. For him, there was nothing as exciting as walking up to that front door, anticipating the hustle. Carlos had all the attributes of a great salesman: enthusiasm, confidence, empathy, and, with bushy black hair and an easy smile, good looks. He knew that once he got inside, he had five minutes to sell himself—to make the stranger comfortable—and then sell the machine.

Nobody worked harder. Carlos was the first to arrive at the office and the last to leave. He closed deals all over the El Paso area—in the more affluent areas near the mountains, in the new suburbs on the East Side, across the border in Juárez. “Shy salespeople have skinny kids,” he would tell his coworkers. “Persistence will always overcome resistance.” His boss, Jose Gutierrez, would hold contests, awarding to the top salesperson $50 and a trophy of a bear standing on its hind legs. He called it the Bear Hunter Award. Carlos won so many that his colleagues started calling him the Bear.

He was in his mid-twenties when he started, in 1982. About five years later he opened his own branch office on Pellicano Drive, eventually employing a dozen salespeople and several secretaries. He called it Jaile Enterprises and had the words written in large type on the building’s facade. Carlos was bent on realizing the American dream—just like his father.

Carlos had grown up in Maywood, a pleasant western suburb of Chicago, the youngest son of Cuban émigrés who fled the island in 1966. His father, Franco, had run a grocery store in Cuba and started another in Maywood that became so successful he also opened a liquor store. Carlos idolized his father and would sometimes tag along and watch how friendly he was with customers, most of whom he knew by name.

Carlos’s cheerful, devout mother, Esther, ran the tight-knit household. Carlos and his three older siblings went to Catholic schools—he was the baby of the family, and his parents doted on him. “He had a big heart, but he was spoiled and he knew it,” said his high school girlfriend Kim Spallone. He was a popular kid and would often play baseball with his friends at fields near his home. When the Cubs were on TV, they would all plan their afternoons around watching the game.

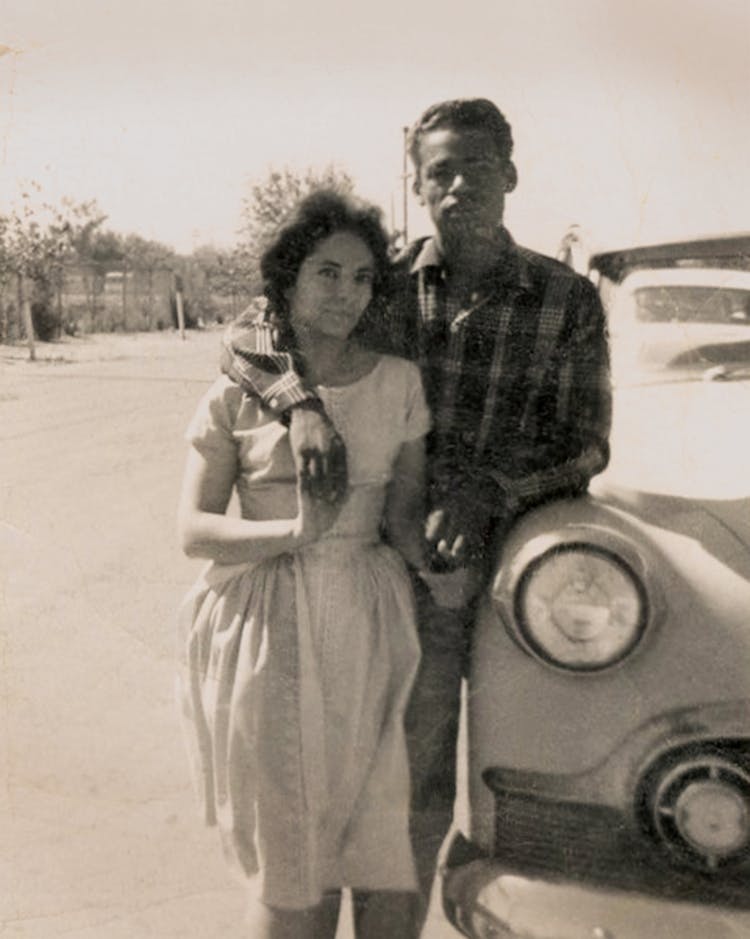

Carlos’s parents had always wanted him to be a doctor, so after graduating from high school, in 1977, he took a few premed classes at a local community college. A former classmate who’d enrolled in medical school in Juárez persuaded Carlos to come check it out. He visited El Paso and liked the city, so he applied and was accepted. Before moving, he and Kim married in Chicago, and once they arrived in Texas, they briefly lived with Carlos’s friend at his ranch-style home on the East Side of El Paso. Their address: 2825 Chaswood.

Carlos and Kim were young and immature, and the marriage didn’t last. In May 1980 they got into a heated argument at another friend’s house. The cops were called, which made Carlos angrier. “What business is it of yours?” he yelled at the officers. They arrested him for criminal trespass and resisting arrest. He was booked, and mug shots were taken. Kim decided not to press charges, but the two officially split that October. Four months later Carlos got himself in trouble again. He was 23 by then and had started dating a 16-year-old. Her mother called the police, and Carlos was arrested and charged with statutory rape. The case was thrown out after the girl insisted the relationship was consensual.

Carlos’s life changed forever in August 1981, when his father died. Much of his ambition came from his dad. “I’d wanted him to be proud of me,” he said. Now he lost interest in becoming a doctor. Carlos dropped out of med school, his future suddenly uncertain. His three older siblings were all in business, and one day he saw an ad in the newspaper promising good money for selling Kirbys. He visited the office, liked the people, and loved the idea of selling this machine, with its powerful motor and distinctive design. Carlos saw his future—and it was in sales.

By this point he was dating a young woman named Pam Yates. She was blond, beautiful, and smart, studying to be a nurse. Soon the two were inseparable. They began talking about starting a family and were married in 1984. The Jailes loved El Paso—the weather, the mountains, the shopping excursions to Juárez. They had a lot of friends and an active social life. Carlos, who spent weekends tinkering with the shiny black Trans Am his parents had bought him for his high school graduation, joined a car club that met at a parking lot near his neighborhood. He felt at home in El Paso and could see himself staying there forever.

And then on June 26, 1989, not long after lunch, a squad car pulled up at Jaile Enterprises. Two uniformed officers walked into the front room and said they were looking for Carlos Jaile. A couple of his employees looked up from their desks. “That’s me,” Carlos said. “How can I help you?”

The cops said they had a warrant for his arrest. Carlos was flabbergasted. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” he protested. The cops handcuffed him and took him away.

Police and prosecutors in El Paso in the late eighties were, they often boasted, tough on crime. The city’s district attorney, Steve Simmons, liked to say, “We don’t make sweetheart deals with criminals.” At the time many residents felt anxious about crimes—both real and imagined—committed against children and young women.

In 1986 two women who worked at a local YMCA day-care center were accused of molesting kids in freakish fashion, including by allowing them to be fondled by “monsters” that the kids described as being twelve feet tall. Each woman was convicted but had her sentence thrown out for procedural reasons. Unsatisfied, single-minded prosecutors came back and tried them again. One was acquitted and the other found guilty, but her verdict was eventually tossed out a second time.

In the fall of 1987 the city was thrown into a panic after the bodies of six teenage girls and young women were found buried in shallow graves in the desert north of town. An auto mechanic named David Wood, age thirty, was eventually caught, convicted of murder, and sent to death row.

Then came the East Side flasher. For two years a man had been driving around the East Side, pulling up next to teenage girls, rolling down his window, and masturbating. The police couldn’t catch him, but they had some good leads. On April 28, 1989, seventeen-year-old Melanie Nieto was walking to school with a friend when an olive-green Cadillac parked near them. The door opened, and a man emerged with his pants around his ankles. “Come here, girls,” he said. The man eventually sped away. Nieto saw him again that day after school—he was, she later told the cops, either Anglo or Hispanic, about five foot five, 140 pounds, with a beard, sandy brown hair pulled back in a ponytail, and a dirty gray ball cap. “He is a very short person,” Nieto emphasized. Her brother, who was with her, told the police the man was five foot three.

A week later, while riding with her boyfriend in his car, she saw him again in the same Cadillac, and they followed him to a house on the East Side. She watched him park in the driveway and walk inside. She called the police and gave them the address: 2825 Chaswood.

Paul Blott, the detective who was investigating the Nieto case, wrote in an offense report, “I checked out this address and learned that subject Carlos Manuel Jaile lives at this address.” In fact, Carlos hadn’t lived there in nine years, but Blott still did a little digging and found a mug shot from one of his arrests. Carlos had facial hair, but otherwise he was nothing like Nieto’s initial description. Carlos was five foot ten and two hundred pounds, and he didn’t have a ponytail or an olive-green Cadillac. Still, Blott put Carlos’s photo in a lineup with four other bearded Hispanic men and took it to Nieto. She picked him out. Blott even told her his name. Two weeks later Carlos was arrested at his office for indecent exposure.

Pam bailed him out, and Carlos figured it was just a simple mistake he could straighten out. But things were about to get a lot more complicated.

Two years earlier, an eight-year-old girl named Maria had walked out of her babysitter’s El Paso house and wandered down the street. A man drove up, stopped, and began talking to her, telling her in Spanish that he was her mother’s mechanic. He was dressed accordingly, and when he asked if she wanted a ride, she said yes. He then drove her out into the desert and raped her. The heinousness of the crime made headlines and shocked the police force.

Maria said the rapist drove a beige sedan. Based on her descriptions, the police made a composite drawing that was used to create a wanted poster, and lead detective Benito Perez made sure both were sent to police stations around the city. Her assailant, she said, was Hispanic and heavyset with a beard. But he hadn’t left any semen, blood, or saliva behind. All that investigators found were a few hairs on her body. The trail went cold.

It warmed up again two years later, in late June 1989. After putting Carlos in that photo lineup, Blott told Perez that he thought Carlos looked a lot like the guy in Maria’s rendering, made two years before. Perez went to the jail to get a look. As he later wrote in an affidavit, “I got chills when I first saw him because he looked just like the composite drawing.”

On June 27, the day Carlos was released on bond, Perez contacted Blott about putting Carlos in a live lineup for Maria. Meanwhile, Blott took a photo lineup to the house of another flasher victim, Kelly Jackson, who was fourteen in September 1988 and had said her potbellied, possibly Hispanic flasher drove a four-door green Cadillac. Jackson pointed to Carlos, who was arrested again on June 28 and charged with another count of indecent exposure. Once again, he thought somebody had just made a stupid mistake that needed clearing up.

His assumption that this was a harmless misunderstanding ended the next morning, when he was escorted from his cell and inserted into a lineup with five other Hispanic men. He had a lawyer with him, who told him why he was there—a little girl had been raped, and he was a suspect. For the first time, Carlos started to worry about forces beyond his control. Maria, ten years old by then, pointed to Carlos as her rapist. “As soon as I entered the room,” the girl said in a statement, “I recognized the man that assaulted me almost two years ago.”

Maria said this in Spanish to detective Lilia Beard, who then translated it into English. At the time Beard was the lead detective on another child-rape case, that of a five-year-old named Andrea, who in July 1987 had been kidnapped and assaulted by a man in a light green car. Beard was well-known in the department. Five years earlier she became the first female valedictorian of the El Paso Police Academy. Now she dealt with sex crimes against children. “She was tough as nails,” said defense attorney Matthew DeKoatz, who often saw the results of her work.

Fifteen minutes after Maria identified Jaile, both Nieto and Jackson were brought in. Three minutes apart, they both identified Carlos as well. These photo and live-lineup procedures, in which the officers in charge knew who the suspect was—and even named him—would not be allowed today. Eyewitness misidentification is a leading cause of wrongful convictions, and in 2011 the Texas Legislature passed a law mandating that police departments adopt written rules about photo and live lineups, including making sure they are “blind”—the person running them shouldn’t know who the suspect is so the witness can’t be tipped off, accidentally or otherwise. Departments now have to draw up written policies about matters such as instructions given to witnesses, with the clear aim of keeping processes regimented, objective, and anonymous.

But this was 1989, and the police felt they had hit the jackpot. According to an El Paso Times story about Carlos, police were looking at him “as a possible suspect in at least two dozen unsolved indecent exposure cases and an unspecified number of cases in which girls have been kidnapped and sexually abused.”

Carlos was soon charged with kidnapping and aggravated sexual assault. He called an older brother, Mario, who had just one question: “Did you do this?”

“Of course not,” Carlos replied.

“Okay. That’s all I need to know.”

His brother flew down from Chicago and took charge. He hired Michael Gibson, one of the best and most expensive attorneys in El Paso. In order to pay for the legal expenses, an investigator, and all of the bonds, Carlos had to sell everything—including his Trans Am and his business. Even more devastating: Pam left him. He phoned her from jail one day, and she told him the marriage was over. “I’m washing my hands of you,” she said. He swore he hadn’t done anything wrong, but she hung up.

Suddenly the entire life he’d built had vanished. Before he’d even gone to trial, it seemed as if everything had been taken from him. All he had left to fight for was his freedom. “Do innocent people actually go to prison?” he asked Gibson, who had worked some four hundred trials in his career.

“Yeah,” said Gibson, “sometimes they do.”

Estella was nervous when she got the notice from the Sixty-fifth District Court to report for jury duty in October 1990. In many ways she felt like an outsider in her own city. She was born in Segundo Barrio, a historic neighborhood squeezed between the Rio Grande and downtown El Paso that was often referred to as the “other Ellis Island” because of all the migrants who passed through.

Her father was a steelworker, and her mother raised their fourteen kids; Estella was number four. Growing up, she slept on the floor in tenement apartments with no toilets or running water. She spoke no English, and even as a kid she ascertained that the better-paid, well-educated white residents of the city were considered first-class citizens, while Mexican Americans, most of whom were poor, were expected to be deferential and subservient. She remembers watching as her mother let white residents talk over her, whether they were at the bakery or her school. Estella didn’t like it, but she found herself falling into the same trap. “Keep quiet,” she was told.

Estella had olive-colored eyes and was so short her friends called her Pulgarcita, or Thumbelina. She was a smart, chatty kid, unafraid to voice her opinions among her friends. She liked school but mostly kept quiet there, because Spanish was forbidden and trying to speak English usually led to other kids laughing at her. Wanting to make her own money, she dropped out during ninth grade. She started babysitting, then got a job doing laundry at Hotel Dieu, the first general hospital in El Paso, making around $100 a month.

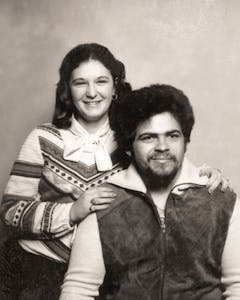

In December 1961, when she was nineteen years old, she took a couple of her younger siblings shopping at the J. J. Newberry department store. She was heading down the escalator, and a young man named Johnny Ybarra Jr. was going up. He was struck by her eyes, and when he got to the top, he turned around and went back down to talk to her. Johnny was a professional boxer, a featherweight, two years older than she was, with a pompadour of thick black hair. They married a month later.

Johnny soon began working for his father, a longtime constable. Through the sixties Estella and Johnny welcomed four sons—Johnny III, Michael, Tommy, and David—and in 1976 the Ybarras bought their first house. To help with the mortgage, Estella got a job in the day care at a local YMCA. But the pay was low, and she decided to pursue a GED. She had to first take a prep class; after making dinner for her family, she would put her sons to bed and study English late into the night. None of her siblings had graduated from high school, but Estella managed to complete her degree.

Still, she wanted more—more money but also to feel more involved in her community, to feel more confident speaking English. El Paso Community College offered a two-year program for an associate of applied science in mental health, which would allow her to work with everyone from teenagers to the elderly. Though some in her family, including her mother-in-law, told her she was too old, she enrolled. She graduated in 1980, at age 38.

Estella took note of the defendant: he was young, and he reminded her of her eldest son, Johnny.

That allowed her to land the job with Lighthouse for the Blind. Estella was good with people and soon was elevated to supervisor, overseeing forty employees and also handling payroll.

When the jury summons arrived in the mail, Estella was so busy at work that her supervisor didn’t want her to go. She wasn’t interested in the judicial system or in politics—she had never even voted for president. But she was picked for the jury. When Johnny dropped her off on the first day in court, December 17, 1990, she couldn’t help but notice that the courtroom was just a few blocks from her old neighborhood. She’d come a long way from Segundo Barrio.

As she took her place in the jury box, she looked around at her fellow jurors. Eight were women, most of them Hispanic, and three were men. Estella took note of the defendant, too: he was young, and he reminded her of her eldest son, Johnny.

Carlos, sitting next to his lawyer, didn’t notice Estella. He was too scared, still trying to figure out how he’d gotten there. His mother and older brother were in the gallery, and he would occasionally look back at them for support. Despite everything, he was confident he would walk out of there, and that he’d leave town and never return to Texas.

There was no physical evidence tying him to the crime, such as fingerprints or hairs, and Gibson put together a strong case, including an alibi defense based on the testimony of three people Carlos had shown Kirbys to on the day Maria was raped. The assault had happened between 1:30 and 3:30 that afternoon, and one of the witnesses recalled that Carlos, wearing a dark suit, visited her home between 1:30 and 2:00. He shampooed and vacuumed a rug and sold her a new unit. In order to have raped Maria, Carlos would’ve had to change clothes, switch cars, cruise the city for his victim, kidnap her, drive into the desert, assault her, return her, switch cars again, change back into his suit, and stop by his office before going out to a final appointment between 4 and 5. Gibson would later say that Carlos’s alibi defense was one of the best he’d ever crafted.

But the prosecution had one of the most powerful courtroom weapons of all: an eyewitness. On the first day of the trial, ten-year-old Maria took the stand; her mother was allowed to sit next to her as she testified. Maria cried as she told what happened to her, and when she pointed out Carlos as her assailant, he noticed tears in the eyes of some of the jurors. He still believed they would use reason, that they would listen to Gibson, who spoke eloquently about the dangers of relying on the traumatized girl’s “powers of recollection” two years after the assault.

While the case was ongoing, the jurors weren’t supposed to talk about the evidence among themselves, so Estella kept her doubts private. Surely, she thought, the others had them too. But as soon as she walked into the jury room, she realized she was in the minority. It was easy for her to write “not guilty” on a piece of paper but much harder to discuss the case confidently as the two white men aggressively advocated for guilt. The old feelings came racing back, the fears of saying the wrong word and getting laughed at. Sitting at the end of the table, she occasionally voiced her opinion that the evidence wasn’t enough. “It’s the life of a man!” she remembers saying.

After a couple hours of heated discussions, she was the last holdout. She didn’t completely understand the legal system, that she had every right to stand firm if she believed the state hadn’t proved guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. But things were getting ugly. “You’re wasting the taxpayers’ money,” one man said to her. “Who do you think is paying for your lunch?” Finally, Estella gave in.

Carlos was stunned when he heard the word “guilty,” as if he had entered some kind of dream state. Gibson was so incensed that, at the punishment phase, when it was time for him to thank the jury for its service and make a case that jurors should be lenient to his client, he instead insulted them. “In some twenty-six long years of prosecuting and defending people in court, trying literally hundreds of cases,” he thundered, “I have never felt compelled or had the opportunity to say the things that I want to say to this jury. I am shocked and appalled by your verdict. A great injustice has been done here. Whatever you do with respect to sentencing can only compound it. I’m sorry, but I can’t find it in my heart to thank you.”

Prosecutor Robert Riley had no problem showing appreciation to the jury—or asking for a life sentence. He got it, plus twenty more years. Carlos was handcuffed and taken away.

Estella was so upset that when she got home, she began sobbing. She’d been weak, she thought, giving in and changing her vote. She talked about it with Johnny, but he told her there wasn’t anything she could do. Drop it, he said. She was a proud member of a law enforcement family, but now the police—with her help—had put someone in prison for something she was certain he hadn’t done. That night she lay awake rehashing conversations from the jury room.

Two things happened in the wake of the verdict: one made her feel better, the other worse. Gibson called to canvas jurors, and he told her she wasn’t alone. Others he’d spoken to had also expressed doubts. “Don’t feel bad,” he said.

Then came the certificate, which she threw in a drawer in disgust.

Carlos was so humiliated by the verdict that he told his brother to inform his Chicago friends that he had moved to Spain, where one of his uncles lived. He was sent to the Clements Unit, a new prison facility and one of the state’s largest, in Amarillo. It was terrifying at first—the constant din, the hostile guards, the occasional violence among inmates. The upper-middle-class kid from suburban Chicago learned to choose his acquaintances carefully, to keep secrets.

He was still convinced he could clear up this terrible mistake. His brother hired an investigator to assist his lawyer working on his direct appeal, but the court ruled against Carlos. He read about a new nonprofit called the Innocence Project, and his brother wrote asking for help, sending along trial transcripts. But the group worked only on cases in which DNA had been a known part of the investigation and trial, and the transcripts were sent back.

A couple of years later, Mario, with his wife, flew down to Amarillo to visit. It was heartbreaking for him to see his kid brother in prison for a terrible crime he knew he hadn’t committed. As the years passed, Carlos’s chances for a normal life slipped away, while Mario raised three sons and ran a successful wholesale meat business in Chicago. “Don’t give up,” Mario would tell his brother when they spoke on the phone. “Something good will happen.” Their mom died in 1996, five years into his sentence. Her death was the toughest thing Carlos ever went through, made worse when he applied for a furlough to travel to the funeral and was denied.

He did a lot of reading (westerns, USA Today) and praying, attending Mass every Wednesday. Some nights he would lie awake in his cot, asking unanswerable questions. Why me? What did I do wrong?

He held a series of jobs, first in the maintenance office, then starting in 2006 in the law library as a clerk. Prisoners would stop in and ask Carlos questions, and he’d help them with forms and dole out advice. Because he was a model inmate, he was granted a job in the prison craft shop, working with wood, creating wall clocks and heart-shaped jewelry boxes, each with a rose carved on the top. Carlos would spend his spare time—sometimes six or seven hours a day—working on the boxes, briefly forgetting his grief. He would sell them to guards, staff, and outsiders. Even in prison he was a businessman: taking orders, buying supplies from vendors, working early until late.

Cubs games were occasionally broadcast on the prison TV, and he watched as many as he could. He had a running joke with friends at the unit: before I die, just let the Cubs win the World Series. Then, in 2016, they did.

Carlos was often confronted with death. Several times fellow inmates killed themselves by leaping headfirst from the third tier. But he was determined to never join them. He believed something good was going to happen, and he repeated the mantra that he once shared with his Kirby colleagues: persistence over resistance.

Estella had troubles in her life too. Her mother had died around the time of the trial, her father soon after. She had high blood pressure and bleeding ulcers, which put her in the hospital. In 1994 she lost her job at Lighthouse. She began a part-time gig as a home health-care worker, and to bring in more income, she and Johnny started an informal resale business at the local Bronco Swap Meet. They would buy mattresses in bulk from La Quinta for $10 apiece, then sell them for $125 each.

She took pride in her sons as they advanced in their careers: Johnny in the Air Force, Michael in the Army, David in the Border Patrol, and Tommy building houses in San Antonio. Every year at Christmas, the family would gather, but she’d still find herself wondering about Carlos. It was an espinita in her side—a little thorn. She couldn’t get free of it. She kept her feelings mostly to herself but occasionally mentioned them to family. “She felt so bad,” said her granddaughter Trisha Ybarra, who credited Estella with pushing her to go to college and to finish her master’s degree. “It would tear her up.”

In 2017 Estella was throwing out some old papers when she came upon that 27-year-old envelope. Inside was the certificate. She called out to Johnny: “This is what I got for putting an innocent person in jail for life.”

She was 75 now. For a generation she had suppressed the shame, the guilt. She had gone through a lot in that time. She’d become more engaged in the world around her. She had seen her children and grandchildren become active citizens. Most important, she’d become more assertive. “I found that you have more power if you talk,” she said. “There’s nothing wrong if you say what you think.”

She knew how hard it was to take a stand. She knew how hard it was to do the right thing. And now she was going to do it.

She called the El Paso Police Department and told the woman on the line that she had been a juror on a 1990 case, and that even after all these years she didn’t think the guy was guilty. The woman told her it was too late to do anything and hung up.

Estella called back and talked to someone else. She explained everything again, recalling details from the trial. This time the person told her to dial the office of Jaime Esparza, the district attorney. Estella called and explained again what was on her mind. She was transferred to Tom Darnold, the head of the appellate division.

DA’s offices get unusual calls all the time, including from jurors having doubts about cases, but usually these come immediately after a trial. Estella was calling about a case from when Bill Clements was governor. She told Darnold what she’d told the others: she didn’t feel right about the verdict. Something she said convinced Darnold to take her seriously, and he promised her he’d look into it. He read the appellate opinion and didn’t see any obvious red flags. He told his boss Esparza about the unusual call from the juror and about his research, and Esparza told him to keep digging. Darnold read the trial transcripts and saw that the case wasn’t the strongest the office had ever prosecuted. He noted the discrepancies with the car and clothes, and also that Carlos had a strong alibi. He went back to Esparza, who decided it was time to take the whole thing to the next level. “We decided,” said Darnold, “just to be on the safe side: let’s look further.”

It soon became clear that in Carlos’s case, the rules had been flat-out ignored.

Esparza called in Roberto Ramos, a longtime assistant DA, and the only person in the foreign prosecution unit, which went after fugitives who fled to Mexico. Ramos was known as a quiet, diligent lawyer who would come in on Sundays to finish his work. His role in Carlos’s case was to be an unofficial one-man conviction-integrity unit. As he later said, “I review the case, which includes the evidence and the testimony. I review our file. I review the work that was performed by our office to make sure that the rules of disclosure have been complied with.”

It soon became clear that in Carlos’s case, the rules had been flat-out ignored. Most of the DA’s file had been destroyed long ago, and Ramos asked his investigator to cast a wide net looking for documents. In early August 2017 the investigator contacted the FBI—and struck gold. The FBI uncovered five letters from 1989 and 1990 between the FBI lab and the El Paso Police Department, addressed to Lilia Beard—the lead detective who had taken the statement from Maria, the young rape victim.

The FBI lab was at the time one of the only places in the country handling DNA profiling, the crime-solving technology that had first been used in Texas courts in 1988. The letters showed that on July 12, 1989, Beard called John Brown of the FBI lab about sending clothes and biological samples from two victims—hair found on Maria in addition to hair and semen discovered on the clothing of Andrea, the five-year-old rape victim whose case Beard had also been investigating. (Police believed Andrea’s case was so similar to Maria’s that for a time the prosecution considered using it to shore up Maria’s case.) Because police suspected Carlos had assaulted the girls, they had also taken biological samples from him—blood, hair, and saliva. Beard then wrote a cover letter about the package she and Perez put together.

The letters addressed to Beard were stunning. The first had arrived January 9, 1990, six months after Carlos’s arrest, saying the hairs found on Maria’s clothes were “unlike” Carlos’s. The second came the next day: the hairs found on Andrea’s clothes were also “unlike” Carlos’s. Four months later—and seven months before Carlos would go on trial—came the DNA results from Andrea’s underwear. The profile had been compared with Carlos’s, and the semen “could not have been contributed by this individual.” These results should have made Carlos the first Texan to be cleared by DNA.

All that digging uncovered another surprise: the district attorney and Carlos’s defense attorney, Gibson, knew about the testing too. In January 1990 assistant district attorney Gina Longoria filed a motion asking to delay the trial because of the testing being done. She wrote that she’d already informed Gibson about the DNA tests. She had even called the lab to talk about the testing in Andrea’s case.

In other words, Ramos’s research revealed that everybody knew about the DNA testing, and even when the results indicated Carlos wasn’t the rapist,

nobody did anything about it.

In July 2018 Carlos was sitting in his cell in Amarillo when he was told to go to the mail room. He was sixty years old, his hair completely gray. The letter that awaited him was from an El Paso lawyer named Matthew DeKoatz, whom he’d never heard of. Carlos walked to the library, sat down, and began reading.

DeKoatz wrote that his firm had been appointed to pursue an 11.07 writ on

Carlos’s behalf. Carlos knew from his work in the library that this referred to a writ of habeas corpus, a potential ticket out of prison for the wrongly convicted. He showed the letter to his supervisor Daryl Glenn, who looked at Carlos excitedly. “You probably got some action,” he said. Tears rushed to Carlos’s eyes. Soon after, he got on the phone with DeKoatz, who told him about the DNA and hair evidence and also explained how all of this had come about—a call from a juror second-guessing the verdict.

Carlos was confident he would finally be going home, but first he had to win the writ. DeKoatz alleged that back in 1990 the state had failed to turn over scientific evidence that would have led to Carlos’s acquittal. He requested a new trial. Judge Patrick Garcia set an evidentiary hearing for November 2018 to see whether the state had indeed hidden evidence.

By day three of that hearing, it was clear that the answer was yes; it was also clear that several El Paso lawyers and cops have lousy memories. Though Carlos’s case was the first involving DNA in El Paso history, few of the players remembered it. His trial lawyer Gibson swore he didn’t recall any discussion about DNA or hairs and said he would have used DNA if he’d known about it. Longoria, who had worked up the case for trial, said, “I have no independent recollection of this case.” She pointed out how all the letters regarding DNA were addressed to the police, not her or the DA’s office. She acknowledged talking to the FBI lab about the testing but said she never saw the results.

Detective Perez couldn’t be at the hearing but filed an affidavit in which he wrote, “I was shown documentation reflecting that I, along with Detective Lilia Beard, requested that the FBI conduct DNA testing in that case and in another case involving similar facts. I do not have any recollection of anything related to that request, including whether or not our department ever received the results.”

Beard, the main character in the DNA saga, wasn’t at the hearing—and wasn’t even subpoenaed to be there. The judge asked where she was. “Your Honor, I tried to get ahold of her, and she wouldn’t call me,” assistant district attorney Rebecca Quinn responded. (Beard, who changed her last name to Medina after getting married, retired from the police force and has been a hospice nurse for more than a decade. She said recently that no one reached out. “If I had been contacted,” she maintained, “I certainly would have gone.”)

Judge Garcia didn’t hold back in his March 2019 opinion, blaming everybody involved in the case for failing Carlos: “It was incumbent upon the state to reveal this information to Carlos Jaile’s lawyer. It appears that the state’s lawyers were in the least grossly negligent if not more in failing to disclose this information and turn it over to the defense. The state’s excuse that they didn’t know about these reports because they were sent to El Paso Police and not the state is unacceptable. The court further finds the defense lawyer was aware these tests were being conducted and should have demanded to know the results.”

The judge acknowledged that DNA testing was new at the time. “But that doesn’t excuse the prosecution in failing to turn it over.” He recommended that the Court of Criminal Appeals grant Carlos a new trial, something the district attorney objected to, arguing that the DNA and hair evidence didn’t prove that Carlos wasn’t guilty. The CCA, which is the state’s highest criminal tribunal, ultimately agreed with Garcia.

The state still had to decide whether to retry Carlos. In the meantime, he would get to post bond—and go home.

In late August a sheriff’s deputy drove Carlos from Amarillo to the El Paso County jail annex, where he lingered for two weeks. Finally, at dusk on September 12, after the judge approved a $30,000 bond, the jail’s electric doors opened, and Carlos, carrying a small bag containing his Bible and a few legal documents, walked out.

Often when wrongly convicted citizens go free, they emerge from the jailhouse with arms raised, joined by smiling defense attorneys as they meet a crowd of well-wishers and journalists, who ask how it feels to finally get justice. Carlos was alone. There were no reporters to ask about the hidden DNA evidence, no prosecutors pledging to do better next time, no defense lawyers patting him on the back. It was as if El Paso officials wanted Carlos to slip away quietly in the night.

He sat on a curb in the dark to wait for his brother, who had flown down from Chicago and was driving over from a nearby hotel. Fifteen minutes later, Mario pulled up. The two hugged, and both began crying. “Thank you,” said Carlos.

“It’s finally over,” said Mario.

Then he asked if his little brother was hungry. Yes, said Carlos. He was craving Whataburger.

As they drove across El Paso, Carlos couldn’t help but look around warily, as if someone might be pursuing him to throw him back in prison. But the next morning they flew home to Chicago, Carlos taking the window seat, still in disbelief as he gazed at Soldier Field shortly before touching down. He moved in with Mario, who, with his wife, Mercy, was an empty nester.

Carlos grew close with Mario’s three sons; the oldest was still a toddler the last time Carlos saw him. On weekends they often took him to play a round of golf or hit a bucket of balls at a driving range. That fall, Mario took Carlos to a Cubs game at Wrigley Field, and Carlos gawked at the ivy-colored walls as they walked into the stadium. When they settled into their seats, Carlos burst into tears.

“What’s the matter?” his brother asked.

“I can’t believe I’m here,” Carlos responded.

He was desperate to start earning money again, and he worked at Mario’s meat shop for a few years. In November 2022 he landed a job with the Illinois Department of Human Services as an office coordinator. In his free time he would visit places from his childhood. One day he found himself at his old elementary school, and memories flooded him as he walked around. He began thinking about his old friend Kathy. They’d met when they were six, and though they were close, they’d lost touch in high school. She was probably married, he thought, but he wanted to find out. One of his nephews looked up her phone number, and he got up the courage to call. It turned out she was retired after 35 years with UPS, divorced, and had a grown son. Talking with her was easy, and they quickly became friends again. Soon he asked her out.

After their date, they went back to her house. “I need to tell you something,” he said, and recounted the story of his last three decades. “You don’t have to believe me,” he reassured her, pulling out several documents he had brought along, including Judge Garcia’s opinion.

As she read, she began crying. She stayed with him, and soon he moved in with her.

I first reached out to Carlos in June 2022, but he wasn’t interested in talking. He’d experienced enough grief, he said, and wanted to put everything behind him. He’d also known other wrongly convicted men who felt betrayed by journalists. I wrote him three more times. His story involved hidden DNA results that should have freed him 32 years ago, I said, and the only reason the genetic testing came to light was because of a juror who was still anonymous. I told him I wanted to track her down. Finally, he agreed.

I flew to Chicago last May and drove through the western suburbs to meet him at a crowded restaurant. Carlos was burly and shy, his hair short and gray. We sat at a booth, and he was initially guarded. When he smiled, his face sometimes curled into something like a grimace. Within ten minutes, though, as he spoke about his father, he was wiping his eyes with the handkerchief he’d pulled from his shirt pocket. The other person whose name consistently brought tears was his older brother. “Mario was the rock,” he said. “And I owe him the world.”

I spent the day with him, talking about his case and his life, from Chicago to El Paso to Amarillo, from successful salesman to convicted child rapist to free man.

He expressed gratitude to both Ramos and the juror. “I don’t know anything about her,” Carlos said. “I don’t even know her name. Maybe I can just say thank you for setting me free.”

The district attorney had finally dismissed the charges against him, but Carlos hadn’t been found actually innocent, a legal classification that would make him eligible for more than $2 million in compensation from the state for his almost 29 years behind bars. From his work in the law library, he knew all about actual innocence: how rarely it was granted and how hard it was to prove—his appellate lawyer didn’t even bother claiming it in Carlos’s appeal, so the judge wasn’t able to consider it.

We also talked about how he could’ve been the first Texan to be cleared by DNA, a dubious honor that instead went to Gilbert Alejandro, of Uvalde, who was convicted of rape in 1990 and exonerated in 1994. I asked Carlos who he thought bore the brunt of the blame for DNA evidence not showing up in his trial: the police, the DA, or his own attorney, Gibson. “Straight-up crooked cops,” he said. “That’s all it was. Plain and simple.”

Everyone involved in Carlos’s case found a reason to look the other way. Everyone, that is, except for one woman determined to do the right thing.

When I later called Beard (now Medina), the former detective insisted she didn’t recall the case. She also insisted she wouldn’t have knowingly hidden DNA testing. “I can’t see any of us intentionally or maliciously withholding that evidence. I mean, if he’s not the right guy, he’s not the right guy.”

Yet Bob Storch, a longtime El Paso defense lawyer, told me, “Back then, cops hiding the ball was standard procedure. If they found that the evidence didn’t meet their purpose or was inconsistent with their theory, they just ignored it or swept it off to the side. They got tunnel vision. When the DNA tests finally came back, the cop may not have even opened the envelope. Probably just threw it in the box.”

Beard’s former partner John Guerrero told me he suspects that the other evidence was given more credence. “I can tell you that in all probability,” he explained, “their whole case was that he was identified in the lineup. ‘Look, we don’t care that you have an alibi. She picked you out. You’re the guy.’ ”

Another case from the same year reveals that Beard was indeed prone to tunnel vision, as was Guerrero. In August 1990 the two interrogated a young man named Orlando Garcia, whose mother had been murdered. After an eight-hour session with Beard and Guerrero, Garcia confessed. He recanted immediately and at trial described how the two had fed him information and intimidated him, with Guerrero pulling his hair and pushing him around. Jurors found Garcia not guilty. When I reached Garcia recently, he told me that, from the start, it was clear Beard and Guerrero had made up their minds about him. “They had their man, and that was me. They never looked for anybody else.” He said that during the interrogation they’d played good cop, bad cop, though he said Beard could be rough too. “I remember her specifically saying. ‘We have you by the maracas.’ ” (She recently denied saying this.)

Of course, it wasn’t just the cops who were at fault in Carlos’s case. The DA’s office played a role. Two lawyers told me that in El Paso in 1990, if prosecutors had doubts about their cases, they were told to ignore them and push ahead to trial—to let a jury settle the issue. “Prosecutors are competitive,” said Charles Roberts, a longtime El Paso defense attorney. “Sometimes they find it difficult to shed the jerseys of their team in the heat of trial preparation and go down investigative paths that might help the defendant.”

And then there was Gibson, Carlos’s attorney, who told me he didn’t recall any DNA tests. “Had I known, I would have been all over it,” he said. He acknowledged that Longoria, the assistant district attorney, might’ve told him about the analysis. It’s possible he ignored the newfangled DNA tests because he already had a strong alibi case.

The truth is, everyone involved in Carlos’s case found a reason to look the other way. Everyone, that is, except for one woman determined to do the right thing.

In the court files, I found the names and addresses of the members of the jury and wrote them letters, laying out Carlos’s story and the role of the juror who came forward. I sent them out on a Tuesday, knowing I was unlikely to hear back. Two days later my phone rang with an El Paso area code. I answered and heard a rapid skein of words, some of which I caught: “Ybarra,” “letter,” “evidence.” I recognized her name and realized that I was talking to a juror. The juror.

We spoke for forty minutes. She didn’t know until she opened the letter that Carlos had been freed—or that she had made it happen. She started crying when she told me about her resurgence of regret each Christmas, and then again when I told her how grateful Carlos was. He’d like to tell you in person, I said.

On July 21 I met Carlos at the El Paso airport. I had no problem picking him out in his Chicago Cubs jersey. As we headed to the Lower Valley, he pointed out a few memorable places from his past, such as the parking lot where the Trans Am club would meet. It was early afternoon as we pulled up to Estella’s small brick home on a sunbaked cul-de-sac.

“You ready for this?” I asked as we walked up the sidewalk.

“Yeah, I think so,” he said apprehensively.

Johnny let us in and led us to the dining room, where we sat together. The house was tidy and spare, the curtains closed to keep out the heat. “Have you been together many years?” Carlos asked Johnny in Spanish.

“Oh, yeah,” responded Johnny. “Since ’62.”

On the wall above us was a photo of Estella taken around that time, her feathered hair hugging her head like a helmet. We looked out over the living room walls, which were covered with photos of their four sons, seven grandchildren, and great-grandson, Lucas. Then we heard a commotion.

Estella, who lives with bad knees, diabetes, osteoporosis, and arthritis, shuffled in with a walker. Carlos stood up.

“Hola, Estella.”

“You must be Carlos,” she said.

He laughed nervously, then asked in Spanish, “Could I hug you?”

“Come on, come on. Of course!” she said. As he moved toward her, she said, “Oh, my god. I thought you were short!”

He reached down and squeezed her. She hugged him back.

“Thank you,” he said, his voice cracking. “Thank you for all you’ve done.” He smiled at her, his arm still draped around her shoulder. “I am so thankful for everything you’ve done for me. You let me out of that horrible place.”

She looked up at him, grinning. “It was my pleasure.”

They each moved to sit at the table. Estella looked over at him. “I feel bad,” she said, raising her arms, “because I didn’t do it sooner, but—”

Carlos shook his head. “If you didn’t do it, I would still be there.” His voice was weak with emotion. “I am so grateful for everything you’ve done.”

“That’s good.”

“Thank you. Thank you, so much. You’re a wonderful person.” He was nodding and blinking tears from his eyes.

“I didn’t forget you,” she said, reaching for a napkin. Now she began to cry.

“Thankfully,” he said.

“Never,” she said, and she lifted her glasses and started drying her tears.

video: Inside the story

Writer Michael Hall spent months reporting this story. Watch him discuss how it came to be, and see the moment when Ybarra and Jaile reunite.

The two fell into easy conversation talking about the trial, which was the last time they were in the same room together. Carlos remembered how he felt sitting in the courtroom. “I was just trying to tune in on everything that was going on, scared to death of what was happening and—why am I even here?”

Estella told Carlos he reminded her of Johnny, her eldest son, and Carlos—who never got over the death of his mother while he was in prison—was drawn to this woman who had mothered four sons.

They talked about their respective histories in El Paso: Segundo Barrio, the old coliseum where he went to a concert and she went to a rodeo. She mentioned the casino on the Tigua reservation, and Carlos brought up the bread he used to buy there when he passed by that part of town.

“It was good,” said Estella. “It was spongy and—”

“Right out of the of the oven!” he finished her sentence. “Oh, you’ve just brought back memories.”

They talked for two hours, this odd couple, each haunted by the past. He told her about his job in Chicago. “I have to work,” he said. “I don’t even qualify for Social Security because I haven’t put enough into it. No Medicare, no nothing. I have to keep on trucking until I can’t no more. That’s my plan for now.”

“You’re starting all over again.”

“I’m starting all over again, yes I am.”

After we left, Carlos wanted to cruise around El Paso. He’d spent years driving the streets, selling Kirbys, and he remembered them well. “The streets got old,” he said, “just like I did.”

We drove past the Chaswood house, his first Kirby office, and his own office on Pellicano, where he’d been arrested 34 years before. He also wanted to visit Pam’s grave. “I loved the woman,” he explained. “She’ll always have a place my heart.” After he was released from prison, he’d hoped to let her know he’d been innocent all along. Then he discovered she’d died of cancer two decades earlier, in 1997. At Restlawn Memorial Park we found her gravestone, which was hidden by overgrown grass, and he laid his hand on the gray slab. “She was young,” he said. “She was good. Also beautiful. Trustworthy. But the sh— hit the fan, and it splattered everywhere.”

Back in the car, he talked about the life he created with her. “I had such wonderful memories of this place,” he said. “My business, my wife, my friends. I considered myself successful. I was making very good money and happily married. And all of a sudden, see you later.”

It was clear he had found some solace sitting with Estella, but he was still wrestling with bitterness. In Chicago, it’s been hard for him to see friends with houses, retirement accounts, children. “I was never able to have a family,” he said. “I would have loved to have a couple of kids.”

He’s an optimist by nature, and it’s still possible for him to receive compensation from the state, though at this point that’s a long shot. Lawyers with the Innocence Project of Texas recently tried one path to remuneration, petitioning the current El Paso district attorney, Bill Hicks, to consider the DNA and hair evidence and assert that Carlos is actually innocent. Hicks declined.

“If I get money,” Carlos told me, “fantastic. Thank you, Lord. And if not, I can’t worry about that. Whatever happens, I can accept it. Whatever life I have left, I’m going to do the best I can and be happy with that.” He gazed out the window at the city he had once known so well, the place he had called home, wondering what could have been.

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Juror Who Found Herself Guilty.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Wrongful Convictions

- Longreads

- El Paso