My love for the San Antonio Spurs came from my mother. She’d once interrupted Manu Ginobili at Morton’s The Steakhouse for his autograph, and the framed receipt still sits on our family bookcase. The first jersey I owned had Tim Duncan’s name and number on the back with light pink detailing. The houses on my street had “Go Spurs Go” spray-painted on their garage doors. When my family would watch the game, the camaraderie and silliness between the Big Three—Duncan, Ginobili, and Tony Parker—showed me what friendship looks like. The greatest Spur of the pre-Duncan era, David Robinson, went to my church. Even if I wanted to get away from the fanfare around a hometown team, I couldn’t. Growing up in San Antonio, the Spurs were everywhere.

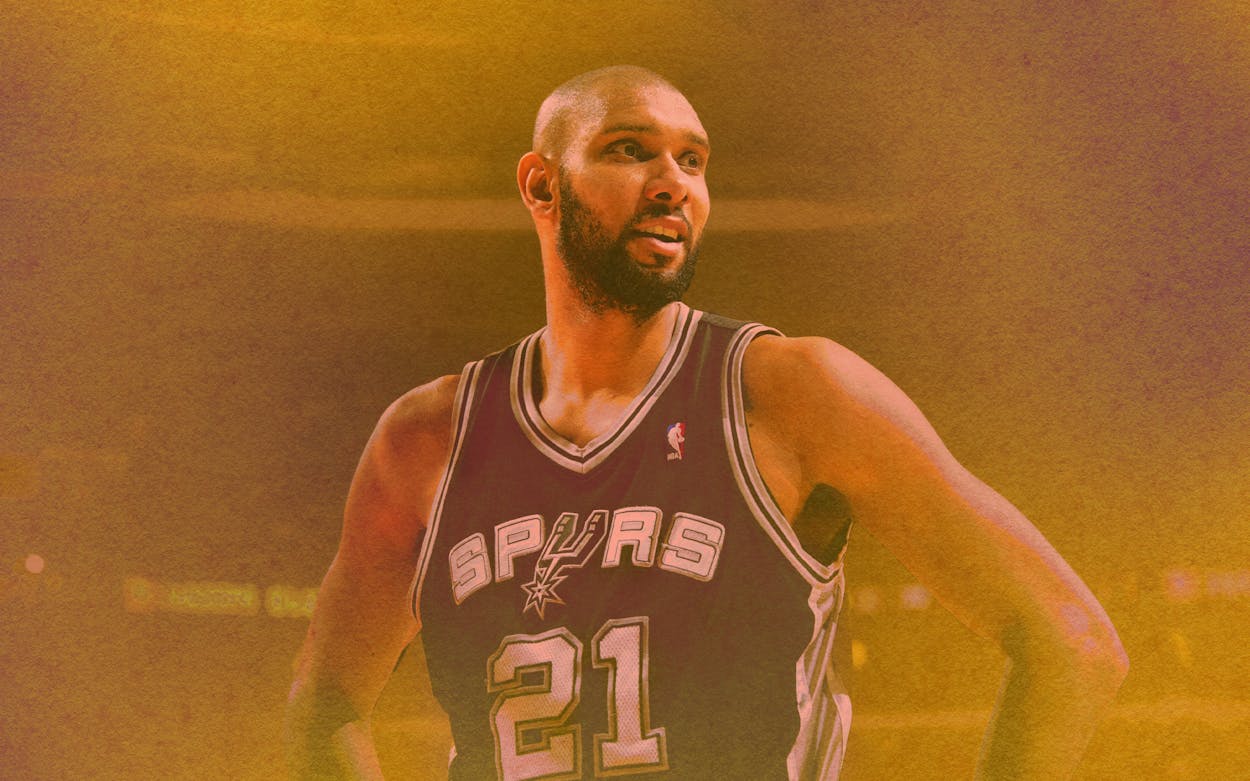

When I was in the third grade, our teacher gave the class a biography assignment. Most of my peers chose subjects like their parents, grandparents, even their childhood pets. I picked Duncan. I dedicated myself to the project, working on a nine-year-old’s version of the comprehensive life story of the great center—how he was raised in the U.S. Virgin Islands, how he had a decorated college career at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, and how the Spurs chose him with the first pick of the 1997 NBA Draft. I believed a figure of Duncan’s status deserved to have his story told in a hardbound volume, so I took a kids book about cheetahs and pasted my pages over the ones inside.

The thing that drew me to Duncan, though, was his story of overcoming loss. See, Duncan had been a competitive swimmer, like his siblings, before he found his way to basketball. Then, after Hurricane Hugo destroyed the pool where Duncan trained, he quit the sport rather than practice in the ocean, because he was afraid of sharks. In 1990, Duncan’s mother died, one day before his fourteenth birthday. As a child, I couldn’t think of anything more terrifying than losing a parent, and Duncan’s perseverance in the face of personal tragedy both inspired me and made me root even harder for him.

As I grew older, I also came to appreciate how Duncan handled being a public figure—by barely ever acknowledging it. One of basketball’s greatest players and Texas’s best-loved celebrities didn’t seem interested in fame at all. Duncan’s demeanor became a pop culture touchstone, referenced in TV commercials and network sitcoms like New Girl, where a character once said: “This moment is so chill and absent of drama, I want to call it Tim Duncan.”

“When you walk into the gym and you see him there before practice or after practice; where you see him with his arm around a rookie, talking to him, just the empathy he has for teammates,” Spurs coach Gregg Popovich has said about Duncan. “His ability to welcome everybody into the culture and make them feel comfortable. . . . He was the base from which we all knew where to operate and how things should be done.”

Duncan’s career accolades make him one of the five or ten greatest players in basketball history: Nineteen NBA seasons, five championships, one team. Since he retired in 2016, Duncan has mostly stayed out of the public eye. Popovich, describing how it felt to continue coaching without Duncan, probably spoke for nearly every Spurs fan when he said: “I miss most his presence. That’s got nothing to do with points or rebounds or blocked shots. His presence.”

- More About:

- Sports

- NBA

- Celebrity Bracket

- Tim Duncan

- San Antonio