She does not know

Her beauty,

She thinks her brown body

Has no glory.

If she could dance

Naked

Under palm trees,

And see her image in the river

She would know.

But there are no palm trees

On the street,

And dish water gives back no images.

In 1926, the poem “No Images,” by nineteen-year-old Waring Cuney, won a literary contest hosted by Opportunity, a prominent magazine of Black culture published by the National Urban League. The poem’s subject is a Black domestic worker or cafe employee standing at the sink washing dishes, worn down by poverty and internalized racism. “No Images” was anthologized in a 1931 collection of Black poetry and reprinted in publications across Europe. Decades later, Nina Simone transformed it into a haunting song she sometimes performed a cappella.

The poem remains by far the most famous work by Cuney (1906–1976), who had deep family roots in Texas and began writing during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. But it’s just one contribution of many from this long-overlooked creative talent. His catalog intersperses socially conscious poems, critical of Jim Crow and gender inequality, with blues-inflected verses lamenting lost love. They were published in literary journals that also printed work by poet Langston Hughes and novelist Zora Neale Hurston. Today, though, Cuney’s work receives much less attention than that of his contemporaries. Two scholars aim to correct that in a stirring new biography of the poet. In Images in the River: The Life and Work of Waring Cuney (Texas Tech, 2024), Cynthia Davis and Verner D. Mitchell explore how Cuney’s Texas connections and his military service shaped his writing. Davis, a professor of English at San Jacinto College, in Houston, and Mitchell, a professor of African American literature at the University of Memphis, collect one hundred of Cuney’s poems, many previously unpublished.

Cuney is often considered marginal even by scholars of the Harlem Renaissance, Mitchell says. “Part of this book is recovery work,” he says. “We’re arguing that he should be considered a central figure.” The book also offers a fuller understanding of Afro-Texan history.

William Waring Cuney grew up in Washington, D.C., near Howard University, his parents’ alma mater. He attended Howard himself for two years before transferring to Lincoln University, near Philadelphia. During college, he met Langston Hughes and began a friendship that connected him with many of the artists of the Harlem Renaissance—even though Cuney himself spent little time in Harlem as a young man.

Cuney didn’t live in Texas, either, but Texas seeps into his poetry—and, as the authors point out in the text, his family members’ lives represent “a microcosm of African American history.” The poet’s paternal great-grandparents were Philip Cuny, a white landowner from Louisiana, and Adeline Stuart, an enslaved woman shipped to his family from Virginia in 1835, when she was seventeen, a decade Cuny’s junior. (The family name later changed spelling to “Cuney.”) Although the power and age differential between the two belies the notion of a consensual relationship, public documents and later family writings suggest Stuart was considered Cuny’s partner. The two moved to Texas, had six surviving children, and maintained a relationship for thirty years, even as Cuny entered legal marriages with white women and freed Stuart. Cuney’s maternal great-great-grandparents also were a white immigrant from Scotland and an enslaved woman whom he later freed.

Cuney’s grandfather and two great-uncles moved in the 1870s to Galveston, which had a rich and flourishing Black culture. Black Galvestonians owned businesses and were active in politics. Post-Emancipation, churches such as Reedy Chapel AME, where the Cuney family worshipped, offered literacy classes, and Juneteenth festivals sprang up to commemorate the reading of General Order No. 3. Davis says the city’s relatively progressive social structure—rare in a Southern city so soon after the Civil War—was a product of its role as an immigration port and its diverse, international population. Exploring Cuney’s biography, she says, is “an opportunity to start a conversation about what really did go on in Afro-Texan history in Galveston.”

Cuney’s great-uncle Norris Wright Cuney is a significant figure in that history. He served as the collector of customs for the Port of Galveston, a federal appointment, and organized a trade union of Black dockworkers. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Galveston and for positions in the Texas Legislature but in 1883 was elected to the Galveston City Council. He went on to become head of the Texas Republican Party, the antislavery party, in the 1880s and 1890s. His tenure ended when he was forced from power by the Lily-White faction of the party, which did not want Black people in positions of leadership. Wright Cuney helped start Central High School, the first Black public high school in Texas, and supported the development of the college now known as Prairie View A&M University. The Cuney Homes public housing complex in Houston’s Third Ward—where George Floyd grew up—is named for him.

Texas makes cameo appearances in Cuney’s poems through references to Galveston and the Jim Crow South. Cuney’s 1962 poem “My Lord, What a Morning” celebrates Black Galveston boxer Jack Johnson’s defeat of his white opponent Jim Jeffries on July 4, 1910. “When the Lights Go On,” a poem Cuney wrote in 1943 after joining the U.S. Army, wonders whether Black Americans will receive equal treatment at home after the war ends. “Will the lights go on in Georgia, Texas—Tennessee? / When the boys come home / After the war— / Will things be bad like before? / Will colored use the back door . . .”

Cuney and Hughes made forays as young adults to Seventh Street, a vibrant but impoverished Washington, D.C., district lined with bars and pool halls. Davis and Mitchell argue that, unlike Langston Hughes, who romanticized the area in his verses, Cuney focused more on the economic inequality and discrimination residents faced. “He always saw himself as a poet of the people,” Mitchell says. “He was proud of his background and his school training, but he always identified with the [down]trodden, and he was just very indignant about Jim Crow and segregation . . . he was very race-conscious, class-conscious.” He also had what Mitchell calls a keen appreciation and empathy for Black women, as demonstrated in “No Images” and “Big Talk,” about a woman ironing clothes and wondering if the wartime talk of “freedom” she hears on the radio includes her.

Cuney’s poems were published in Opportunity, the Harlem Renaissance outlets Challenge and Fire!!, and the NAACP magazine The Crisis. He counted the poets Hughes, Sterling Brown, and Countee Cullen among his friends and colleagues, and he participated in the literary salon of playwright and poet Georgia Douglas Johnson.

But today, Cuney is not a household name. In general, Black writers and artists of the early twentieth century had little access to fellowships, the mainstream press, and other promotional tools that could ensure their work was remembered. Cuney also kept his distance from the Harlem Renaissance patron and publicist Carl Van Vechten, a white man who connected Black writers with opportunities but whose affection for Black culture bordered on fetishization. Davis and Mitchell conclude that Cuney’s decision not to engage with Van Vechten may have lowered his profile compared with other artists such as Hughes. Cuney also lacked descendants who could’ve preserved or promoted his work.

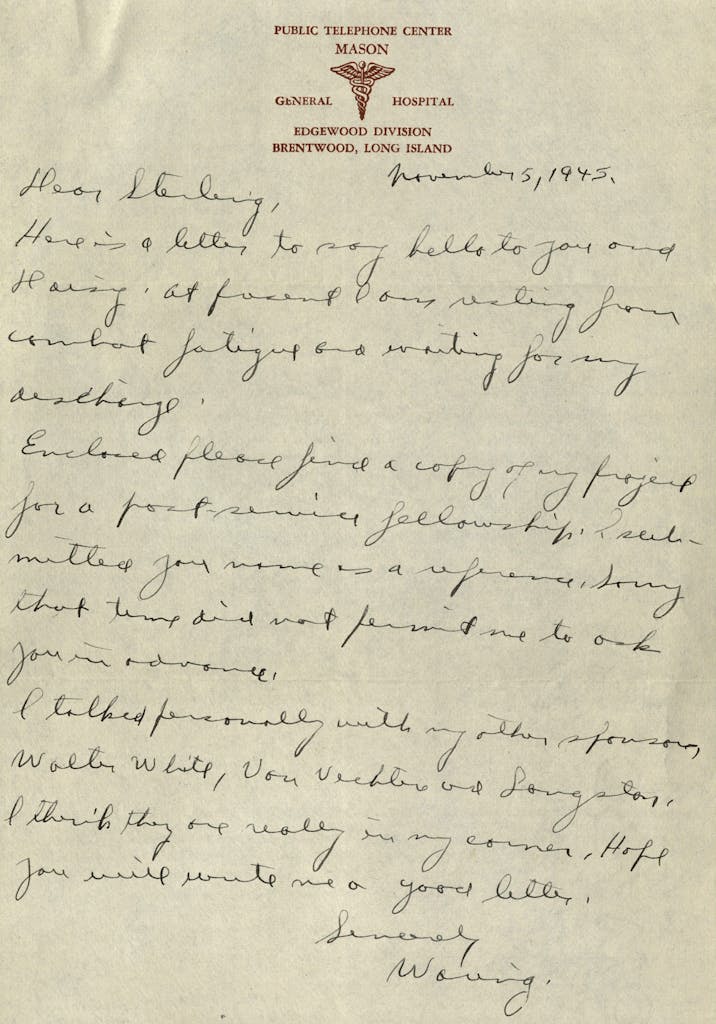

Cuney enlisted in the Army in July 1942, served in the 857th Engineer Aviation Battalion, and was awarded three Bronze Stars. When he wasn’t building runways in the rainforests of New Guinea and the Philippines, he wrote poems and songs, which he sent to Hughes for safekeeping, but his mental health was declining. He was hospitalized for “combat fatigue,” or PTSD, from May 1945 until his unit came home, after which he received additional treatment.

After the war, he continued to write but was no longer immersed in the literary scene. In 1960 he published his first poetry collection, Puzzles, after which he withdrew almost completely—likely due to mental health challenges, Davis and Mitchell suggest. In the last two decades of his life, Cuney’s closest relationship was an enduring romance with Adeline Norris, a white nurse from Wisconsin, although the two never married or lived together. He published his second collection, Storefront Church, in 1973, three years before he died.

In assembling Cuney’s poems and delving into his biography, Mitchell and Davis aim to restore the poet to a central position among Harlem Renaissance writers. Mitchell likens their project to Alice Walker’s early-1970s efforts to revive interest in Zora Neale Hurston, whose books had been out of print for at least a decade. “What Cynthia and I are doing is revisiting the Harlem Renaissance and arguing for a more prominent role for some of these people who haven’t been studied,” Mitchell says. In the process, they have recovered a complex family story that offers a window into Texas history.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Galveston