Every August several hundred of the most socially prominent men in San Antonio secretly elect themselves a queen. The queen is chosen not on the basis of her beauty or talent, but on the length of her bloodline and the health of her father’s bank account. She reigns over Fiesta, San Antonio’s annual spring celebration held each April in honor of the Battle of San Jacinto, Texas’ final victory over Mexico. The young woman with the oldest family and a father who can afford to blow $50,000 on a gown, a robe, and ten days’ worth of parties, wins.

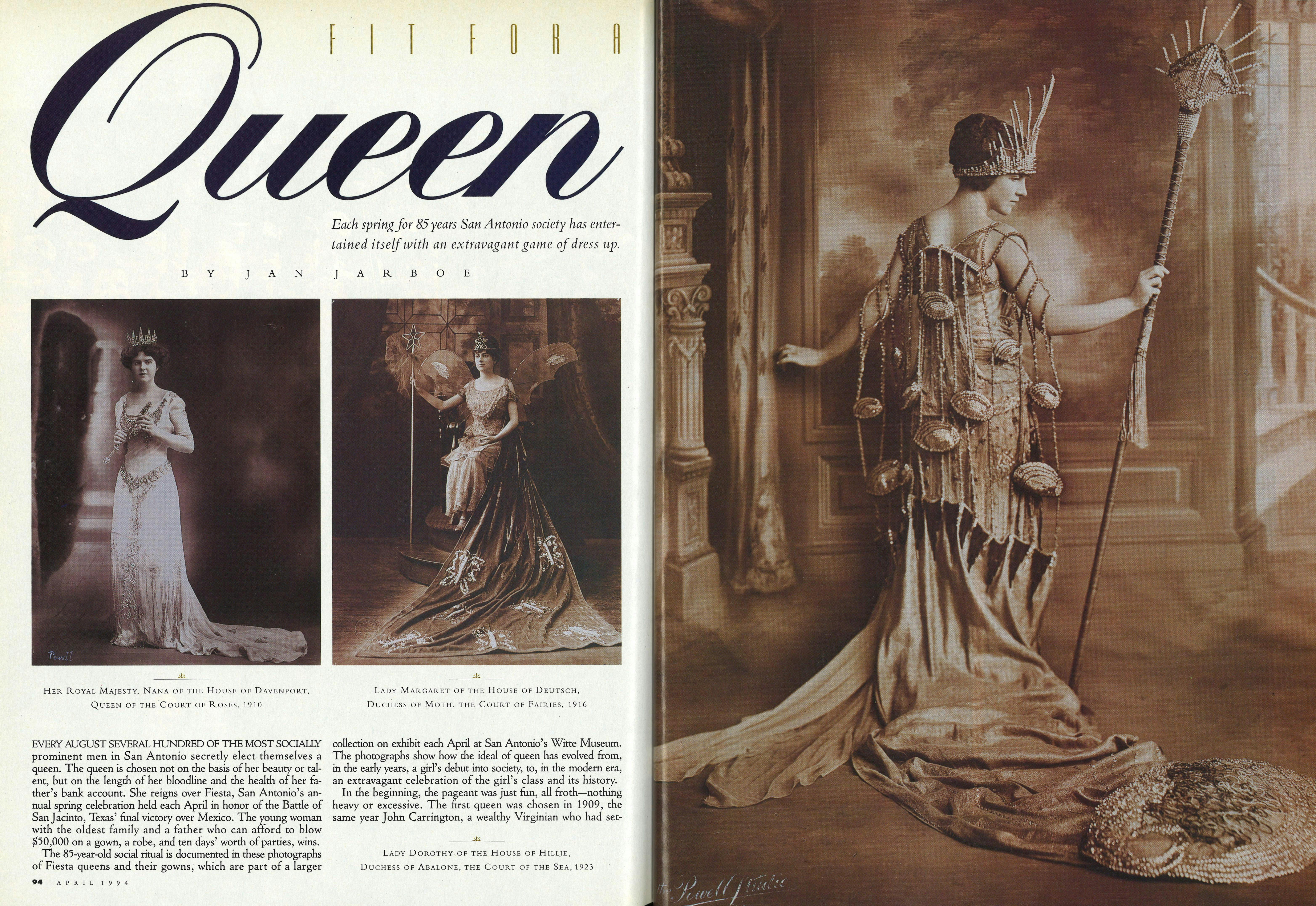

The 85-year-old social ritual is documented in these photographs of Fiesta queens and their gowns, which are part of a larger collection on exhibit each April at San Antonio’s Witte Museum. The photographs show how the ideal of queen has evolved from, in the early years, a girl’s debut into society, to, in the modern era, an extravagant celebration of the girl’s class and its history.

In the beginning, the pageant was just fun, all froth—nothing heavy or excessive. The first queen was chosen in 1909, the same year John Carrington, a wealthy Virginian who had settled in San Antonio, formed the Order of the Alamo. According to the organization’s charter, the Order had two purposes: to choose a queen to preside over a court of 24 unmarried girls and boys, and to “educate its members and the public generally in the history of the Independence of Texas and perpetuating the memory of the Battle of San Jacinto.”

The idea was to set a romantic scene against the backdrop of Texas history. The photographs show that the early courts were light, airy, and full of fantasy. As Carrington intended, romance blossomed. The first queen, Eda Kampmann, chose Order founding member J. H. Frost as her prime minister; the two were married and bore children who later made their debuts into society during Fiesta. In just this manner, San Antonio’s upper class has continued to set itself apart—the majority of queens have come from the same dozen or so primarily German and English families.

Each of the coronations has a theme that is stitched on the gown, and many of the earlier, more beautiful gowns glorified nature. For instance, the first court was the Court of Flowers, then came roses, followed by a Carnival of Flowers, then lilies, then spring. In 1916 Margaret Deutsch, a duchess in the Court of Fairies, wore a short gauzy gown with moth wings and carried a star-topped staff. In the early days, the girls were allowed to choose their own colors and their family seamstresses made the dresses. They were free to experiment. Edna Steves was Queen of the Court of Birds in 1920, and her short dress with a train of hand-stitched peacock feathers was more of a costume than a serious gown. Marie Elaine Lange wore a harem-style ankle-length gown in the Court of Aladdin in 1922, and the following year, Dorothy Hillje, Duchess of Abalone of the Court of the Sea, wore a gown decorated with seashells.

In the twenties, thirties, and forties, the Fiesta gowns still followed fashion. Some were cut on the bias, so slinky that one slim duchess from a South Texas ranching family reportedly wore no undergarments beneath her gown. The queens were photographed under mood lighting in elaborate studio settings. Often the girl was perched on a simple pedestal between palms or Grecian columns. The trains were of such little importance that often they didn’t appear in the photographs.

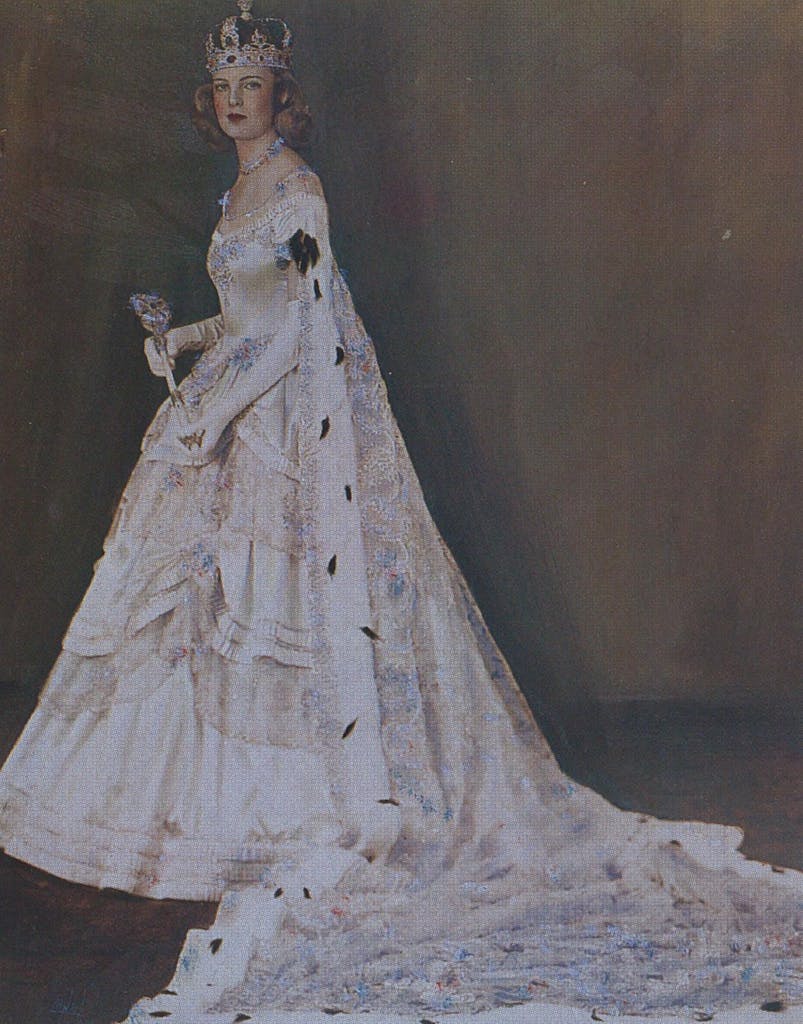

It was when the gown was asked to carry the weight of history—as well as the girl’s family lineage—that the ritual became a burden. You see it start happening in 1936, when Mollie Bond Hayes was Queen of Texas and the Court of Adventure, a celebration of Texas’ centennial. That year the text of the coronation read: “Alien peoples . . . imbued with the spirit of adventure and love of freedom have appeared from the east to claim the land . . . the hour of departure of the Indian has arrived. ” In this particular historical fantasy, the Indians do not die.

Over time, the gowns have become symbols of the dream of wealth and exclusivity. “It’s like a grown-up fairytale,” explained Ellen Maverick Dickson, a former princess in 1951. “The whole thing is a metaphor for saying, ‘We can do this and you can’t.’” The coronation of the queen continues because of mutual desire: The girls want to wear the dresses, and their fathers, the 850 members of the Order of the Alamo who are descendants of the bankers, oilmen, and cattlemen whose money built San Antonio, long to give their daughters what they want.

As the price of oil continued to rise and family fortunes grew through the fifties, sixties, and seventies, the gowns became more lavish and expensive. Each year’s court tried to outdo the last. Trains went to twelve feet for duchesses and fifteen feet for queens, and layer after layer of beads and rhinestones were added. Now some gowns with trains weigh up to 85 pounds, and the dream seems suffocating. By the mid-seventies, the cost of each gown had risen to as much as $35,000 and the emphasis was on the garment. For the past few years in the official photographs, which run in a special Sunday supplement of San Antonio’s newspaper, the gowns completely engulf the girls. “The worst thing happened when I went for my final fitting,” recalled Sarah Spohn Kleberg Johnson Pitt, who was Queen of the Court of Never-Never Land in 1983. “I tried to lift my train, but I couldn’t. It was too heavy.” Pitt’s prime minister helped her carry the train. Other queens have resorted to weight training and daily vitamin B12 shots, and when all else failed, some have put their train on rollers.

Naturally, what is regarded by some as a symbol of beauty and tradition is regarded by others with, at best, ambivalence. In the mid-seventies, when Mexican Americans were making a new drive for political power in San Antonio, former city councilman Bernardo Eureste publicly called the Anglo royalty of Fiesta “a joke.” In 1972 the superintendent of the predominantly Mexican-American Edgewood School District banned the annual visit of the Order’s king and queen to the district’s schools. Beginning in 1981, a “Cornyation” was held at the Bonham Exchange, the city’s largest homosexual bar, where ordinary San Antonians, dressed in knockoff Fiesta garb, crown a queen. (For the last five years, the Cornyation has been held at Beethoven Hall.)

Still the gowns themselves are seductive. Seeing them up close—to feel the heaviness of the velvet and the weight of the beads and rhinestones—it is impossible not to be drawn to them. They are reminders of how ethereal and enchanted a place Texas can be, especially when money is no object. “I don’t see what the big deal is,” said one former queen, gaily. “I loved being queen. My grandmother was queen. My mother was queen. All my cousins have been in the court. To me, it’s just fun and tradition.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Style & Design

- Photo Essay

- Fashion

- San Antonio