I think it was the snow-white standard poodle with the matching fuchsia collar and leash that caused my first symptoms of cosmic dissonance. It was February, and I was at Tootsies, forever one of Houston’s most fashionable stores, and arguably the most Houston of Houston’s fashionable stores, to check out a rodeo wear party, an act that was already causing me some mental disturbance. That was partly because the marquee lights spelling out the word “RODEO” were blinding, the countryish music was blaring, and the racks and racks of clothes in the designated stomping grounds were adorned with enough denim, fringe, and studs to gussy up the entire female population of San Angelo. Even more disorienting was finding myself surrounded by super glam twenty-, thirty-, and even sixtysomethings rushing the cash register to pay for a lot of stuff that looked like what I refused to wear in high school.

In the middle of it all was that unlikely breed of cow dog—the poodle, standing so still in an aisle that I thought he was a prop, maybe left over from a previous fashion event (like, a French one). Turned out, he was attached to a big-haired, blue-eyed, cowboy-hatted shopper who was beaming broadly while sipping from a flute of champagne that made her even giddier at the prospect of adding more Western wear to her wardrobe. She already looked pretty well outfitted to me, in a denim skirt, a Western shirt, a bandanna, and cowboy boots, but clearly, I was the fashion-challenged one. “When you go, you gotta dress the thing,” the customer explained. “The thing” was, of course, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo—in her case, ostensibly viewed from someone’s private box—but more important were all the rodeo parties, most of which, she added, almost as a self-correction, were “for charity.”

A second pass among the rodeo-wear racks was even more bewildering. The Tootsies stylists had pulled together some big names in fashion—Moschino (Italy), Nili Lotan (Israel-born), and Cinq à Sept (New York with French aspirations), along with the edgier Nanushka (Budapest!)—whose work clearly evoked, but cost a whole lot more than, the stuff traditionally found at Western wear superstores Boot Barn and Cavender’s. “Western is not just . . . rodeo,” a Tootsies saleswoman explained to me, because now the same ensembles are needed year-round in “Aspen, Round Top, and Marfa,” apparently the golden triangle of Western wear.

Just adjacent to the high-priced designer clothes—the thigh-hugging punched-leather pants and breath-defying denim corsets—was a rack of far more classic cowboy gear from Schaefer Outfitter, the Austin-based Western wear company that’s been around since 1982. Seeing this brand at Tootsies was, to me, like seeing chicken-fried steak on the menu at Nobu, but Schaefer owner and local philanthropist Robert Clay, there to promote the line, set me straight. “There’s ten thousand ranchers and hundreds of thousands of guys in dusters,” he explained. “Western’s broken through. Everyone wants to be a cowboy.”

I couldn’t argue with him. The rodeo months of February and March have always meant that the Houston stores and media push rodeo dressing, but something bigger and more expensive seems to be going on. The River Oaks District, home to Hermès, Dior, and Brunello Cucinelli, is offering hats by Teressa Foglia, most in the four-figure range (the one-of-a-kind Raul comes broken in, or, as the description online puts it, “entirely distressed by fire,” for $3,200). Miron Crosby’s boutique at the end of River Oaks Boulevard features “boots for fashion girls,” including a special model, the Sophie, emblazoned with the word “y’all,” for $1,895. At Pinto Ranch down the street, the abundant selection offers the option to dress like an old-fashioned Dale Evans cowgirl (some fringe) or a Stevie Nicks cowgirl (lace and fringe) or a Beth Dutton cowgirl (no fringe, just weathered black leather). Those searching for an understated look can opt for a scarlet-and-white clutch beaded with the word “Howdy.”

Western dressing is all over Instagram, where the unschooled can follow influencers, such as Texas twin sisters Hailey and Kailey—Daniels and Fletcher, respectively—who go by doubleshotofsass, posing on their home pages in cowboy gear. Of course, Texas’s biggest fashion influencer, Beyoncé, has enshrined the style, most recently in 2023, by wearing a “disco cowboy hat” to promote Renaissance (it was designed by a woman from Philadelphia), and again at this year’s Grammys. Teasing her country-influenced album, Act II, she sported an ensemble from Pharrell Williams’s new collaboration with Louis Vuitton paired with a white Stetson.

Dressing like you are heading to watch the calf scramble at NRG Stadium is now ubiquitous—or, if you aren’t a fan of the style, unavoidable. “This spring, just about everything is Western,” a Tootsies saleswoman told me. Indeed, virtually every high-end designer this season is featuring cowboy boots, including Louboutin, Prada, and, yes, Vuitton. “Altering the rules of high fashion, Pharrell has used this opportunity to spotlight American Western style with his artistic twist,” Sneaker Freaker breathlessly declared of the musician’s creative directorship with the French design house. One of Ralph Lauren’s latest ads shows a model wearing a jacket that could have belonged to General Custer (before Little Bighorn) and a Western-style belt buckle so big it looks like she won it for bull riding. Somewhere between Village People and Beyoncé, Lil Nas X helped revitalize the style for the queer community. Among the TikTok-minded, the look has a new name: “cowboy core.”

Clay of Schaefer Outfitter was understandably thrilled at all these developments. A silver-haired real estate developer and a member of the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo Salt Grass Trail Ride, he suggested that the passion for Western wear was all about “independence” and “Americana.” He’d brought along his CEO, a very tall man named Jason Smith who wore a pristine Stetson and a full-length duster, and a sprightly, dark-haired press representative, Dana Barton, who had on a Western-cut suede jacket. No one looked like they had spent much time in the West Texas sun, unless they were crossing a street in Marfa.

Barton had her own theories about dressing Texan—COVID-19 had inspired people to appreciate “a simpler way of life,” she spitballed—but I had stopped listening. My attention had wandered. Specifically, to her jacket. It was a rich sorrel hue with a lush shearling collar, dyed to match. It was double-breasted and sashed at the waist, with Western-style stitching below the shoulders. It hugged and enhanced her form. On a nearby rack, the same jacket’s tag said $595, which suddenly seemed like a perfectly reasonable price for an article of clothing for a place where climate change is rapidly eradicating winter and—more to the point—in a style I had spent my entire life avoiding. This must be what it feels like to be abducted by aliens, I thought.

There comes a time in most people’s lives when they are forced to question bedrock beliefs. Some might ponder changing political parties or converting to a different religion. Confirmed cat people might discover their love of dogs. A steak lover might at least try to go vegan. My visit to Tootsies was that kind of moment: entranced by that jacket, I had to ask myself what my aversion to “dressing Texan” was all about.

For decades, my excuse was that putting on a cowboy hat or a snap-button shirt stirred up all sorts of unpleasant associations: elementary school bullies with thick Texas accents, my dismal failure as a barrel racer at a Hill Country camp, stifling August cookouts in Boquillas Canyon with Budweiser-chilled parents, the agony of dateless Friday nights after flipping flash cards in a freezing high school football stadium for hours, only to be followed, in college and beyond, by Yankees demanding apologies for, among many other things, JFK’s assassination, LBJ’s presidency, the Dallas Cowboys, and so on, right up to the presidencies of Bush 41 and 43, with David Koresh and the siege of Waco in between.

All of the above actually happened, but it happened so long ago that recounting it today makes me feel like a vaudeville comedian struggling to repurpose musty material. After all, no one forced me to come back to Texas in the late seventies. In my adopted hometown of Houston, I eat the enchiladas and barbecue of my youth with gusto, use the term “all y’all” without shame or irony, shudder when an Anglo speaks Spanish with a crummy accent, and relish any and all visits to friends’ ranches, no matter how long the drive and how uninhabitable the land. A recent hop onto a quarter horse almost brought me to tears. Why should a party-invitation dress code specifying “Texas Chic” fill me with dread?

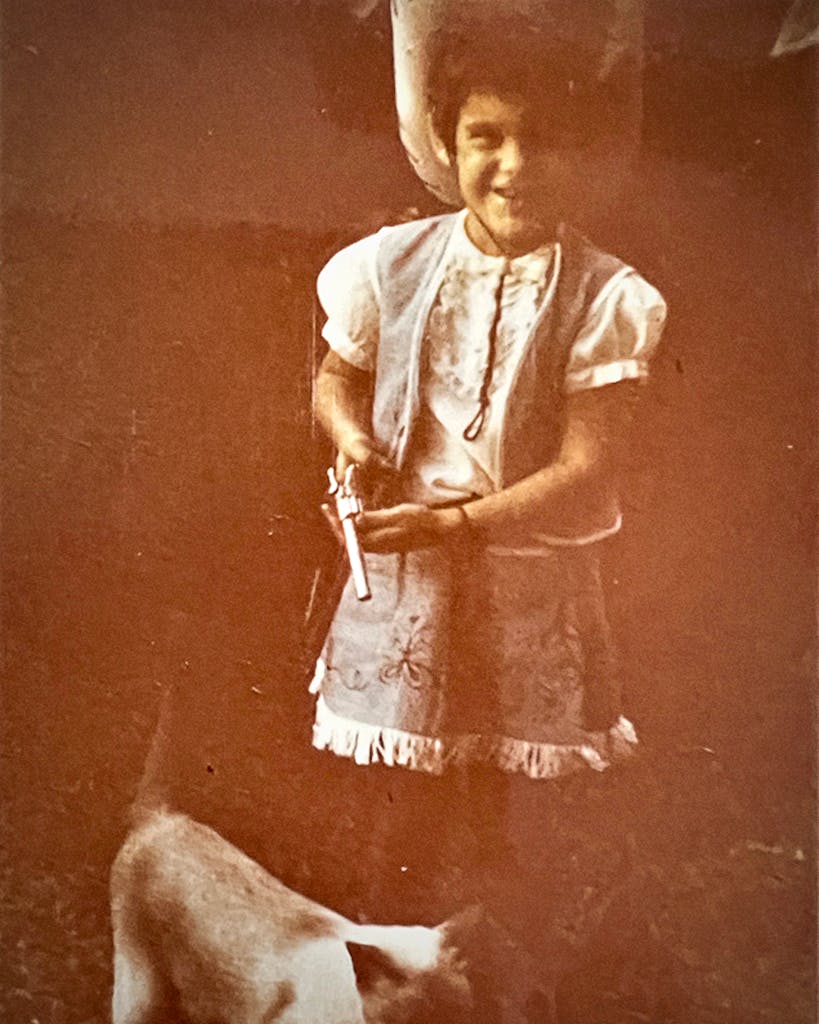

I know I didn’t start out that way. I grew up in 1960s Texas and recently came across a photograph of five-year-old me in a cowboy hat, fringed vest and skirt, and boots; I appear to be gleefully demonstrating how to load my toy six-shooter. In those days, I also had a plastic, bowlegged Dale Evans who fit perfectly on top of my many, many plastic horses. I was taking riding lessons before I started first grade. My parents took me to the dingy, dusty Freeman Coliseum on the East Side of San Antonio for the rodeo every year.

But to be Texan then, contrary to popular belief outside the state, didn’t mean I came from people who spent their days herding cattle and cooking from a chuck wagon. I come instead from a family of clothiers, which means that dressing was never a casual act but was instead a method of communication and, probably more saliently, an avenue for value judgment. My father’s father made clothes: he and his Marx-like brothers had a factory that made men’s suits in Baltimore that sold to Washington politicians—a Saturday Evening Post story about them was titled “They Suit the Big Shots.” My mother’s father had a clothing store, mostly menswear, that had been in his family on Alamo Plaza since 1868; my maternal great-grandfather outfitted Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. I got my jodhpurs and derby for horse shows there. (For reasons that now seem snobbishly clear to me, I rode English instead of Western saddle. Buckskin jackets were not an option in competition or, for that matter, at my grandfather’s store.)

My Baltimore-born dad abandoned the opportunity to inherit his family’s suit-making business but wound up working for a decade or so as a salesman for his father-in-law. Except for a time—an embarrassing period to me—in which he paired his long hair with a longer mustache and a guayabera, his casual look included Brooks Brothers’ polos paired, due to uncomfortably flat feet, with custom Luccheses. He wasn’t trying to be a fashion plate: the company was founded in San Antonio in 1883, and even in 1963 the boots did not cost nearly what they do now, which can come close to the price of a serviceable used car on the west side of town.

My mother was the kind of clotheshorse for whom being fashionable was a first line of defense against what she saw as San Antonio society’s rigidity and, simultaneously, the East Coast conviction that all Texans were rubes. (For that reason, Robert Sakowitz’s decision to open the first Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche boutique in the U.S. in Dallas was more earth-shattering to Mom than the moon landing.) This created in my psyche a fashion conflict that began in high school but has lasted to the present day. Then, as now, I mostly wore jeans and a T-shirt—see: rebellion, against not just Mom but also the Farrah wannabes in my high school. Still, as a teenager I could distinguish Calvin Klein from Donna Karan and Donna Karan from Giorgio Armani in the pages of Vogue, and today my Instagram feed is full of designers I can neither afford nor wear. When I dress up, I receive dubious compliments like, “Wow, you clean up good.”

While I was getting indoctrinated at home, Texas in the sixties and seventies was transforming itself from a rural to an urban state. This meant, among status-conscious kids—and my high school was full of them—that “shitkickers” were even lower in the social order than the burnouts who smoked cigarettes just beyond the school’s south wing. By that time, in my circles, the rodeo was a vestige, a novelty, something “world-class cities”—and every city in Texas dreamed of becoming just that—wanted to leave in the dust while lusting after designer skyscrapers, NFL stadiums, and shopping malls with ice-skating rinks. To dress like a rodeo queen meant you were “country,” a nicer word for not very smart.

Then, to the surprise of nearly everyone, in the late seventies and early eighties, Texas became cool to the rest of the world. Probably for the first time in its history. The oil boom made it all happen, of course, but there were the cultural exports too: Larry L. King’s 1978 Broadway hit, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (funny Texans!) and Dallas (superrich Texans!). North Star Mall got in on the celebration—or relief—by installing Bob “Daddy-O” Wade’s “world’s largest pair of cowboy boots” in a paean to Texas style.

Simultaneously, Ralph Lauren made his phenomenally successful move into Western wear. Ignoring the singing cowboys of Hollywood—“It wasn’t Roy Rogers wearing rhinestones,” Annette Becker, director of the fashion collection at the University of North Texas, told me—Lauren opted to create his own interpretation of cowboy style. An ad from the time shows him posing in a sepia-tinted photograph wearing a subtly tweaked ensemble that includes an understated string tie, a perfectly weathered work shirt, and, yes, a suede fringed jacket, but one so supple and free of excess adornment that Upper East Side ladies who lunched would want to be swaddled in it. “The spirit of Western style has a rugged elegance and authenticity that people want to relate to,” Lauren insisted soon after premiering his line of Western wear in 1978. “There’s both a sensibility and honesty to the clothing that gives it an enduring appeal.” Not to me.

I had recently moved from Massachusetts to booming Houston after graduation, and my hypocrisy meter was happily married to my big-city airs. First, as UNT’s Annette Becker said of her childhood, Laurens “weren’t the jeans I grew up wearing. The jeans I wore had cow s— on them.” My Gap jeans didn’t smell like a barnyard, but I didn’t see why anyone would pay a zillion dollars to look like an inhabitant of the backward, backcountry Texas I had once been desperate to escape.

I held my ground even at the crowning moment of Texas chic, as it was called: the premiere of the megahit Urban Cowboy, in 1980. It was based on an Esquire magazine story by Texan turned New Yorker Aaron Latham. Like Ralph Lauren’s getups, the article and the movie that followed were infused with nostalgia. The only memorable bovine in the movie is a mechanical bull that comes to signify the loss of wide-open spaces, “manly” men, and the women who cook and clean for them. The main character, Bud (John Travolta), is a refinery worker who longs to get home to Spur and own a ranch. Latham was from Spur, too, a Manhattan celebrity married to CBS broadcast star Lesley Stahl. I doubt he was desperate to return to the wilds of Dickens County.

The premiere took place at the not-very-pastoral Gaylynn Theatre, at Houston’s Sharpstown Mall. Stars Travolta and Debra Winger showed up in character. (Looking at those pictures today, I can admit that the blue-eyed, dimpled New Jersey heartthrob looked born to wear a Stetson.) Also present were Mesquite-raised supermodel and Mick Jagger courtesan Jerry Hall, in head-to-toe silver (silver cowboy hat, skintight silver pants, an open-to-the-waist silver fringed blouse); designer Diane von Furstenberg, sporting a cowboy hat and a bandanna and tiger-striped pants; and her partner, Barry Diller, the picture of unease in a pearl-snap shirt. Lynn and Oscar Wyatt looked like the real deal, she in a cowboy hat with peacock feathers and a suede dress with seductive cutouts, he in a string tie, a belt with a Longhorn head on the buckle, and a black cowboy hat—highly appropriate, given his surly reputation in the oil patch. Andy Warhol was seemingly the only celebrity to abstain from Western wear. He’d probably just had enough of authentic Texas by then: “We had frogs’ legs and beef and chicken and shrimps, everything barbecued and chilied and guacamoled” he wrote in his diary. “And it was so hot out, it was like ninety-five degrees. And the air conditioning broke down. . . . And then we went to a few Western shops to get our costumes for the Urban Cowboy premiere.”

Note the use of the word “costumes,” a term that perfectly describes the way I felt when I started a tenuous flirtation with Western wear around the same time. Trying to join the fun, I summoned the courage to buy an understated pair of Tony Lamas, but after a few self-conscious tryouts, they ended up in the back of the closet. This was partly because they pinched my toes, but also because I felt like I was playing at being Texan whenever I put them on. I didn’t hang out at ranches, I didn’t listen to Willie or Jerry Jeff, and I couldn’t do the two-step if it was the only way to free my son from kidnappers.

Fortunately (for me), the pressure to dress Western was conspicuously absent during the ensuing oil bust. It seemed like a fitting metaphor that the founder of the now-defunct Cutter Bill stores, a real rancher named Rex Cauble who created a Texas-wear empire, was convicted of drug smuggling during the dreaded bust year of 1982, a time when no one wanted to remotely resemble a Texan of any kind. (Maybe it was a tip-off that the then-president of Cauble’s company showed up at the Urban Cowboy premiere in a fur jacket and fur cowboy boots. It was, after all, June.)

George W. Bush brought Texas style back in the early 2000s, changing the symbolism along the way. The president’s critics labeled him a “cowboy”—and not in a good way—so putting on those boots meant you’d taken his side. The polarization to come was obvious from day one, at the inaugural Black Tie & Boots Ball, now sponsored every four years by the Texas State Society in D.C. “For Texans, it’s all about the boots,” read an AP headline about the second edition, going on to describe it in Margaret Mead–visits–Samoa terms as “the only party in town where the 10,000 guests are not just encouraged but expected to pair down-home duds like Stetson hats and Tony Lamas kicks with tuxedos and evening gowns.” The attendees were largely big-time donors, government officials, and lobbyists, most of whom hadn’t dodged a cow patty for decades, unless it was a metaphorical one. A party photo from January 2001 shows the newly elected President Bush comparing his boots with those of then-governor Rick Perry and then-senators Phil Gramm and Kay Bailey Hutchison, whose scarlet pair matched her ball gown. I’m sure they’d all put in their time on South Texas dove hunts, but something about the photo struck me as performative, celebrating a Texas exceptionalism that’s caused more harm than good as the years have gone by. Ann Richards and Molly Ivins could challenge a hoary stereotype by donning a hat and boots—the gear belongs to Texas Libs too, after all. I could not.

Now, after an extended hiatus, the wheels of fashion have turned again. My Western wear issues have come flying back into my sartorial consciousness. “It’s very accepted and normalized,” Jessica Mooney, director of merchandise for the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, said about the return of Western wear. “We want branded merchandise that we can wear in real life, not just ‘I’m the cheesy cowgirl going out on Fridays.’ ”

Once again, Texans are behind the move. Taylor Sheridan has become the unofficial spokesperson for hardheaded, anti-government, lonesome-cowboy realism, and maybe for that reason, Yellowstone was initially a hit with more conservative viewers. The New York Times chief TV critic, for instance, suggested that the show capitalizes on the culture war between those who live in red-state flyover country and those who live in coastal blue states, the latter described in just-kidding shorthand as “Bankers. Lawyers. Vegans.” (Having watched Sheridan’s entire oeuvre, including the turgid 1923, I would say the show speaks to anyone with a passion for melodrama, a tolerance for unnecessary violence, and an appreciation for a good sit on a Western saddle.)

What cannot be disputed is Sheridan’s Midas touch in the style department. “Everything came together with Yellowstone two years ago,” Schaefer owner Robert Clay told me. “Taylor Sheridan’s been good to us.” According to Clay, Sheridan’s people contacted Schaefer’s people, seeking “authentic” Western wear for Yellowstone. Kevin Costner, who until recently played the ranch patriarch John Dutton, then wore one of Schaefer’s vest-and-jacket pairings on the show. The result: the company sold around 3,500 pieces of the ensemble almost overnight. I admit to a soft spot for Beth Dutton, but I don’t think her falling-out-of-her-clothes style would work in most C-suites, even in Texas. Maybe especially in Texas. My mother would suggest that $595 Schaefer jacket, buttoned up and belted.

The authentic, sexy, and powerful Western-wearing woman of the moment is, of course, Beyoncé. She’s always telegraphed something Texan in her style (you can take the girl out of Houston . . . ), but the clothing and accessories became more explicitly Western with the debut of Renaissance, in 2022, then got deadly serious with Act II, which set off the predictable Bey-induced fashion frenzy. (A press release from a British PR agency that recently landed in my inbox claimed that after Beyoncé showed up in Western regalia for the Super Bowl, web searches for “bolo tie” increased by 566 percent and “cowboy hats” by 212 percent. Maybe the bolo seekers already had hats.)

Beyoncé’s take on cowboy style, of course, has an entirely different purpose than that of Taylor Sheridan. As New York Times fashion director and chief fashion critic Vanessa Friedman suggested to me, Beyoncé in Western wear embodies “the reclamation of Western mythology and righting of old wrongs through honoring the legacy of the Black cowboy.” As an LGBTQ icon, she tells another story. UNT’s Becker expanded on the point by asserting that Western wear “is not coded by gender,” an observation that could probably send some old cowboys around the bend (and maybe make some other ones glad). “It’s hard to tell what’s coded male or female,” Becker said, asserting that bolos ties, fringe, and chain stitch embroidery now belong to everyone. “There are a lot of ways Western wear can be read right now. So many people can see themselves in it.”

“It’s fashion,” Tootsies creative director Fady Armanious clarified, helping me shrug off the weight of my rodeo-wear crisis. For most people, dressing like a cowboy or cowgirl has become just another option in the closet, and any historical or cultural reference an outfit makes is no longer a big deal. Think of cargo pants, aviator sunglasses, or the buttons on suit-jacket sleeves. Once, those items signified a time, a place, and a use. Now they just look good. They can mean whatever a wearer wants them to mean on a given day.

Maybe I’m getting there. I did buy a pair of not-too-flashy, not-too-expensive Tecovas after receiving yet another invitation, with a name like “Boots and Bubbly” or “Country Couture” or “Cowboy Rustic,” asking me to dress like a Texan. The knee-high, brown suede boots look good with jeans and a T-shirt—duh—and are very comfortable. I like the way I feel when I walk in them—like Beth Dutton on a good day, when she doesn’t feel like she has so much to prove. Like I’ve finally made myself welcome in my own home.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Western Wear

- Fashion

- Cowboy Hats

- Cowboy Boots

- Houston