Looking back, I don’t think my initial reaction to Victor Emanuel was out of line. I first encountered his name years ago, when George Plimpton, who was giving a reading at the Texas Book Festival, spotted a trim, friendly-looking man entering the room. Plimpton beamed as if the president of the United States had just sauntered in. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he bellowed, “Victor Emanuel!” If memory serves, Plimpton tried to get the audience to applaud. Not recognizing the name, I leaned over to a colleague sitting nearby. “Who is that?” I asked. “He’s a birding expert,” she said. My response was something along the lines of “Who cares?”

As it turns out, plenty of people. Over the years, Emanuel has gone birding with a wide variety of high-profile clients, among them Laura Bush, Prince Philip, filmmaker Terrence Malick, Nobel Prize–winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann, and former U.S. treasury secretary Henry Paulson. He has traveled with the famed naturalist Peter Matthiessen for many years and appears in Matthiessen’s books The Birds of Heaven and End of the of Earth.

Eleven years ago, George W. Bush was on the campaign trail in Cleveland, Ohio, and told the crowd about an epiphany he had had after inviting Emanuel to his ranch in Crawford. “You know what you ought to do?” Emanuel had told him. “You ought to go down and look at the birds.” Bush had replied, “I’m a bird-shooter. That’s all I’ve done as a kid—you know, I shoot ’em.” On that occasion, however, he just looked at the birds. Years later, standing at the lectern, he gave voice to a sentiment that has been expressed by many people, no doubt with a hint of bewilderment: “So I went birding with Victor Emanuel, and it was fabulous.”

None of this is to imply that Emanuel is a birder to the stars; he’ll bird with anybody. And besides, in birding circles it is Emanuel—not the company he keeps—who is the star. Thomas Hornbein, who was part of the first expedition to climb Mount Everest by the West Ridge route, told me, “I have a fair bit of notoriety in mountaineering, and frequently people will recognize me. When I’m with Vic, the roles are reversed.”

Though Emanuel, who lives in Austin, operates one of the oldest ecology tour companies in the world, that alone doesn’t account for his renown. Nor is it the intensity of his obsession with birds that draws people to him; many other die-hard birders are just as obsessed. Emanuel can bombard people with statistics and avian trivia, but that isn’t the source of his appeal either. What he offers is different, and hard to define. There’s something about Victor Emanuel that will cause a random hiker to approach him and say, “Mr. Emanuel, there is a pygmy owl about a hundred yards back up the trail, and it would mean so much to me if I could show it to you.” And then, upon returning home, brag that he went birding with Victor Emanuel. And that it was fabulous.

Despite some hearing loss that occurred in childhood, Victor Emanuel is a remarkable guide. Roger Tory Peterson, who wrote and illustrated a widely read series of birding field guides, once suggested that Emanuel and another Austin tour guide, Rose Ann Rowlett, have “the sharpest eyes in Texas,” capable of identifying a bird at a glance. It’s conceivable, of course, that Emanuel is simply so familiar with the landscape that he just knows where a certain bird is likely to be. “Victor has a superb memory in regards to all the rivers and all the birds and all the people he has met,” said one friend. On a second trip to a far-flung locale, for example, he will remember that there’s a bend in the road just ahead with a fence post that’s ideal for, say, a white-tailed hawk to stop and rest and, upon rounding the corner, will see that a white-tailed hawk agreed.

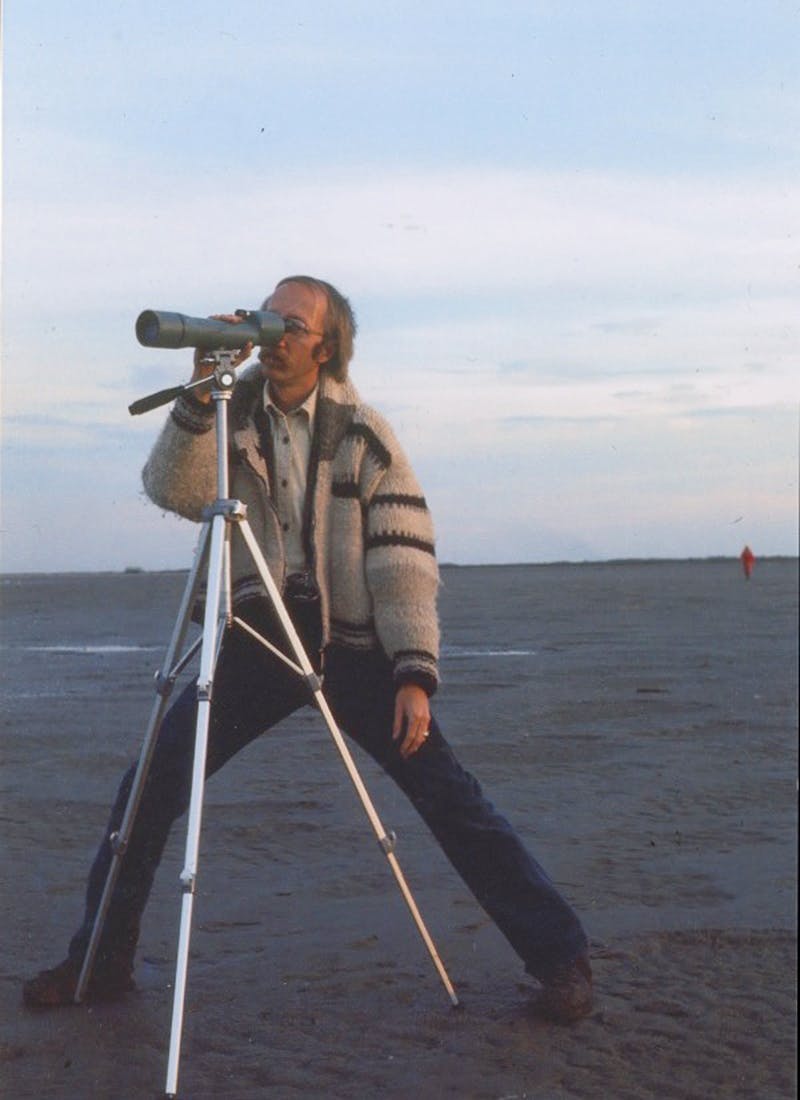

One day last fall he and I patrolled an Austin park, scanning the perimeter for wildlife. Emanuel is seventy and bald on top, with a half-moon of white hair hugging the back and sides of his head. He walks at a good clip and dresses as if modeling for an REI catalog. A few minutes into our tour he spotted a flash in a tree. Quickly, he brought his binoculars to his eyes. “Ruby-crowned kinglet up there,” he said. “That tiny thing flitting around up there is a bird that may have come from Canada. See it there? Upside down? It’s called a ruby-crowned kinglet, and it’s a tiny little bird. Flits around. Very flitty. One of the things it eats is spider eggs.” I looked through my binoculars and saw a grayish-yellow bird that resembled a sleeker version of a sparrow. “There it is. Very flitty. See how it flits its wings a lot? That’s typical. If you learn the behavior you don’t even have to look at it. Nervous little bird.” I tried to follow the bird as it moved around. Emanuel continued watching it without his binoculars. “You might wonder, Why is it called ruby-crowned? Well, under the feathers on top of its head is a brilliant red pom-pom, like a burst of red, like you stuck a piece of red cotton on its head. When it gets angry or upset or wants to say, ‘Back off, this is my area,’ it puts up its red pom-pom. That’s why it’s called ruby-crowned.” I put my binoculars down too. All I could make out was the tree.

When looking at a bird, Emanuel will often whisper, “Wow!” He can be tranquil one second and animated the next. When I called him one day, he interrupted our formal greetings to shout, “There’s a Cooper’s hawk outside my window—I’ll call you back!” and hung up. He has no filter for his excitement. He will bring a car to a screeching halt and run through the brush to get a better look at a bird he has seen through his windshield—mosquitoes, rocks, gates, cougars, and snakes be damned. According to witnesses, he was once so excited to see penguins swimming five feet off the shore in a little bay in the Galápagos Islands that he ripped off most of his clothing and strode into the water.

“There used to be a term in the early days: ‘bird lovers,’” he told me as we walked, giving a quick overview of the nomenclature. “‘Bird lover’ sounded a little bit drippy, a little bit mushy. Then there were ‘bird watchers’ and then we had ‘birders’ and that—” he halted abruptly. “Look on the water fountain. There’s our state bird.” He paused to get a good look through his binoculars before the mockingbird flew into a nearby bush. “So birders, to some extent, don’t just watch birds,” he continued. “They try to see as many as they can. But a bird lover—actually, in terms of my feeling about birds, I’d be closer to that.”

Though we can assume reciprocation is out of the question, it’s uncanny how the birds seem to reward his dedication. Years ago, Emanuel was standing in the front yard of Austin author Lawrence Wright when a bird called. “Did you hear that?” Emanuel asked. He began to search for the bird, telling Wright it was a yellow-billed cuckoo and that it sounded as if it had a caterpillar in its mouth. It did.

Victor Emanuel was probably the type of kid whom adults call “wise beyond his years.” It’s a description that doesn’t usually bode well for a child’s social life. In the late forties, most boys in Houston were interested in sports or comics; they weren’t impressed, as Emanuel was, with the color of red cardinals on green moss or the murmur of a hummingbird feeding on mimosas. But Emanuel wasn’t alone in his pursuit for long. When a fellow Cub Scout told him about the Outdoor Nature Club, which met at the downtown library, the nine-year-old showed up for a meeting and realized he had, finally, found his people. He soon dropped out of his Cub Scout troop, even though most of his new friends were decades older than him.

During Emanuel’s first few years with the club he spent enough time in the field that he learned to differentiate between the loud ta-wit, ta-wit, ta-wit, tee-yo of the hooded warbler and the trilling twe-twe-twe-twe of the pine warbler. He began to notice which birds soared and which flapped their wings continuously. He taught himself to swiftly pop his binoculars in front of his eyes so that he could get the best view of the quick chimney swift and the vermilion flycatcher, whose red coloring is so brilliant that it appears to be glowing. Emanuel couldn’t get enough. He’d keep an eye out for the chickadees and ruby-crowned kinglets hopping on branches in the water oaks as he walked to school each day. On weekends, he’d page through Peterson’s Birds of Eastern North America and examine the book’s glossy plates. Some of the birds were exotic, with bright colors and stripes and patterns and weird, long tails. Some had mohawks or plumage shaped like soft-serve ice cream on their heads. Others were totally bald and wrinkly, with whitish warts near their eyes.

To any child interested in nature, the peculiar details of the world’s birds have undeniable appeal. The hoatzin in South America smells like manure. The helmeted hornbill in Borneo laughs maniacally. Cassowarys have been known to kick (and even disembowel) people. Peregrine falcons can dive at speeds of up to 200 miles an hour. The more attention Emanuel paid, the more he noticed that even ordinary birds—a rock pigeon, say—began to seem exotic.

And the beauty of it was, he didn’t have to travel far; he was born in a birder’s mecca. In Texas, a diversity of landscapes—the Panhandle Plains, West Texas desert, East Texas forests, and Gulf Coast—offer cover to a wide variety of species. Northern Plains birds meet Mexican varieties along the Rio Grande; eastern birds meet western along the hundredth meridian. There are about twenty North American species that can be seen only in Texas. The state also boasts a large population of migratory birds passing through, particularly along the upper Texas coast, where Emanuel lived. “If I had been living in the Panhandle, it wouldn’t have been the same,” he said.

His pursuit did not thrill his father (also named Victor), a sports editor for the Houston Post who sometimes freelanced as a campaign manager for Democratic politicians. (His mother, who was interested in birds but no expert, was somewhat more sympathetic.) The elder Victor’s appreciation for nature began and ended with reading his son The Jungle Book at bedtime and visiting the zoo. Instead, he worked hard to instill in his son a passion for politics. He introduced young Victor to luminaries such as Sam Rayburn, Lyndon Johnson, and Eleanor Roosevelt when they came through town, showing his son that there was no reason to be nervous around famous people.

This interest in birds concerned him. “Here was this son who was different from the other boys, who wasn’t a normal kid, and what would this lead to?” Emanuel said. “My dad would have been much happier with a son who was a baseball or football player.”

Emanuel tends to inspect coincidences closely, examining them for a tinge of magic. How did two of his friends happen to know each other? How did you know he was about to call you? He will marvel at the fact that, when he was fifteen, one of his mentors in the nature club happened to mention that the coastal area of Freeport was rich with gulf birds and bottomland woods. This information started a chain of events that would change Emanuel’s life. At his mentor’s prodding, he founded a Freeport outpost of the Christmas Bird Count (essentially an annual bird census). Emanuel, who persuaded about ten people to join him, drew a fifteen-mile-diameter circle on a map of the area and ended his first count with a respectable 114 species.

He continued sending postcards and letters every year to potential participants (“I’m a stick-with-it kind of guy,” he explained). Even as he went to the University of Texas to study zoology and botany and then, skeptical that he could build a career as a birder, on to Harvard to study political science as a graduate student, he continued to head up the Freeport CBC. By 1972 the participating group was big enough and the birding conditions good enough for the Freeport group to win that year’s national CBC competition: 226 species counted. The timing was ideal, since the media, who were interested in the growing birding phenomenon, paid a lot of attention to the latest CBC winner. When Audubon magazine sent George Plimpton to Freeport the following year, Emanuel’s status as a birding authority was pretty much established. Soon afterward, Plimpton introduced his new friend to his old friend Peter Matthiessen.

Still, Emanuel couldn’t make a living as a birder, though he had had some encouraging experiences. In 1970, Emanuel recalled, “a man came to Houston from Decatur, Illinois, named Dean Gorham. He was about seventy years old. He was a banker financing home building, and he came to a convention for home builders.” Here’s where, according to Emanuel, fortune intervened. Gorham asked the local head of the National Wildlife Refuge for a bird guide and was given Emanuel’s number. “I’m twenty-nine years old. I’m living in one room that I’m subletting from some friends, and I get a phone call. Dean Gorham calls me and says, ‘If I paid you one hundred dollars, would you take me and my sister out birding for the day?’ I practically dropped the phone.”

He couldn’t believe his luck. Emanuel helped Gorham and his sister find all five of their target birds, including a white-faced ibis and a sprague’s pipit, and walked away with a hundred bucks. Thinking there might be other interested parties for personalized birding tours, he took out an ad in Birding magazine. “Using me was as cheap as renting a car,” he said. “I valued myself as nothing. Zero. But I needed the experience.” While he struggled to grow his business, Emanuel taught political science at Rice University and worked as an organizer for school board elections. In 1976 he finally felt confident enough to launch Victor Emanuel Nature Tours.

Two years later, when he moved to Austin, he was hardly the lone birder. Besides the folks in the Travis Audobon Society, there were about a dozen enthusiasts who hung out with the eccentric naturalist and godfather of Texas birding, Edgar Kincaid. The nephew of J. Frank Dobie, Kincaid did not like most people, but the birders he liked received a high honor: a bird name. Kincaid granted Emanuel’s request to become the hooded warbler, a cute little thing with a bright yellow face and a sweet, high voice that sings, “Weeta-weeta-weet-y-o.” According to his friends, it was fitting. “He’s hyperactive,” Rose Ann Rowlett once explained, “but profound.”

For a brief period after starting VENT, Emanuel still felt the pull of politics. When his close friend Mike Andrews ran in the 1980 Democratic congressional primary for the Twenty-second District, Emanuel was recruited as his campaign manager. During the week, Emanuel commuted from Austin to the campaign headquarters in a Houston shopping strip near Hobby Airport. He was helping his friend as a favor, but his heart wasn’t in it. That’s when he received the sign that it was time to stop dividing his energies. “We had a front office and a back office,” Emanuel recalled. “I was in the back office, dealing with all this campaign management stuff. One day I was at my desk, sitting there, and I hear ‘Bob WHITE. Bob WHITE.’ The building was made of cinder block. I walked around the back of the building, where there was a vacant field of grass, and there was a post right behind my office with a bobwhite quail sitting right on it. The sound came into the room like it was calling me back.”

His ultimate decision to leave politics mystified some of his colleagues. A birder named Lola Oberman, who had been a speechwriter for Lloyd Bentsen, told me that one time she stopped by Bentsen’s Houston office to meet with some colleagues and told them she had come to Texas to do some birding. “You should meet Vic! Vic what’s-his-name,” one of Bentsen’s people said. “We hoped he would go into politics, but he went into birding instead, and we haven’t heard from him since. What a wasted life.”

In the early part of the twentieth century, people trying to identify a marbled godwit, a black-whiskered vireo, a horned grebe, an Eastern towhee, or any other species of bird were left to their own devices. Assistance arrived in 1934 when Roger Tory Peterson produced the very first field manual to birds. It sold out within two weeks. Later editions fueled the pastime, and by the late sixties the enthusiasts, who by that point had gone from calling themselves bird lovers to calling themselves birdwatchers, formed an elite group: the American Birdwatching Association. Since many of the hobbyists were isolated practitioners, wandering through fields in no-man’s-land with their binoculars and guidebooks, it took a little while for word to get out. In 1968 the ABA’s official newsletter, Birdwatcher’s Digest, was a five-page mimeograph sent out to ten people; a year later membership had crept above one hundred.

This small group of pioneers enjoyed competing with one another, keeping a tally of how many species they had seen over the course of a day, a year, a life. ABA co-founder G. Stuart Keith, one of the first to keep a “life list” (at the time of his death, in 2003, he had seen more than 6,500 bird species, or about two thirds of the roughly 9,000 species that exist), suggested a new nomenclature to differentiate the fanatics from the backyard hobbyists who didn’t care about the finer points of pishing and ululating. And so, in 1969 “bird-watchers” became “birders,” the American Birdwatching Association became the American Birding Association, and Birdwatcher’s Digest became, simply, Birding.

The years that followed saw an explosion of interest in hard-core birding. Stories began to circulate about people like sixteen-year-old Kenn Kaufman, who dropped out of high school, hitched rides across America, ate cat food, and lived on a dollar a day just so he could beat the record of 626 species seen in a year. After a failed attempt in 1972, he did so in 1973, with an amazing 671 species. In the decades since, enthusiasm has only increased. The ABA, whose current membership is roughly 12,000, is full of birders who will spend many hours and dollars to find rare species, risking life and limb in the process. Phoebe Snetsinger, who in 1995 became the first person to see more than 8,000 species, suffered shipwrecks, earthquakes, and a gang rape. The British ornithologist David Hunt was killed by a tiger in 1985 while leading a bird tour in India, and his posthumously developed photos show that he was snapping pictures up to the very end. (According to Bill Oddie’s travelogue Follow That Bird! “The final picture is of a frame-filling shot of the tiger’s head, eyes blazing and teeth exposed in a snarl.”)

Emanuel, too, will go out of his way to see an unusual bird. On March 22, 1959, he received a call from Houston birder Ben Feltner and his friend Dudley Deaver. Feltner and Deaver told him that they had been out on Galveston Island and had spotted a lone Eskimo curlew in a field of long-billed curlews. The Eskimo curlew, at the time, was thought to be extinct. A stunned Emanuel went down to Galveston a few weeks later to verify the sighting. As he and his entourage headed for the spot where Deaver and Feltner had seen the bird, Emanuel noticed a field where shorebirds were feeding alongside dairy cattle. “Let’s look at these birds,” Emanuel said, stopping to scan the group. Within minutes, he spotted it: a small curlew about a foot long with a thin, slightly down-curved beak. It was the rarest bird he has ever seen. In terms of birding, he said, “It was the most thrilling thing that’s ever happened to me.”

One sunny afternoon last fall, Emanuel was walking around his neighborhood in South Austin with his $2,000 binoculars around his neck when he spotted one of his favorite species. “It’s up on that bare branch,” he told me. “It’s called a yellow-rumped warbler, and it winters here. It’s so neat to see that and think, ‘That bird bred in the spruce forest of Canada. And here it is.’” He has seen so many yellow-rumped warblers in his lifetime that one might expect him to practically yawn through the sentence. But even though he enjoys the thrill of the odd bird, Emanuel, it turns out, does not share his colleagues’ enthusiasm for bird quests. “Obsession with the new and obsession with collecting the list means you’re losing so much beauty that surrounds you,” he said. “This bird is the product of thousands of years of evolution. It is not just another bird.”

“So when you see a bird,” I asked, “is that how you think of it? Here’s thousands of years of evolution?”

He put his binoculars down and looked startled by the question. “No,” he said firmly. “I just think it’s beautiful.”

This could well sum up Emanuel’s philosophy. It is, ultimately, the reason for his reputation. “Victor is the Zen master of birds,” said Matthiessen. “He looks at the bird directly for itself. He’s not attaching or anthropomorphizing at all. He just sees it and appreciates it for what it is right at that moment, without forming abstract ideas about it.” Matthiessen added with a note of exasperation that listers are not much fun to bird with. “They keep dropping the names of birds,” he said.

Still, sometimes Emanuel’s avian egalitarianism can seem extreme. Once, Emanuel and Bob Thornton, a conservationist and wildlife photographer in the Metroplex, were on a boat in Austin’s Lady Bird Lake. When the boat pulled up to the shore, Thornton remembered, “There was, of all things, a grackle, one of the most common and least-loved birds on the planet. Victor had to direct everyone’s attention, in high decibels, to the grackle.”

Being the Zen master of birding can be tricky, of course, when it’s your job to find rare birds. “There’s a bird in the mountains of southern Mexico called the horned guan,” Emanuel told me one day. The horned guan, which looks like a cartoonist’s joke, is one of those rare species that people will pay a lot of money to see. “It’s a big bird—black above, white below, with a red horn on top of its head,” he said. “Very strange bird. Yellow bill. And they’re secretive; they live up in these giant trees.” To see unusual birds like the horned guan, many birders will hike to remote areas, wake up at god-awful hours in the morning, and pay VENT anywhere from $1,000 to $10,000 per trip, knowing all the while that drought or development or unforeseen weather patterns can chase a population of birds away. It is the guide’s job to make birds appear, regardless of the conditions. “You feel the pressure,” Emanuel said.

These days, VENT takes clients on 160 tours in more than one hundred destinations annually: places like Bhutan, Botswana, Machu Picchu, Cambodia, Panama, Brazil, and Kazakhstan. Tours go by names such as “The Montana Owl Workshop” and “Best of Borneo.” Many tours were scouted by Emanuel himself. He fine-tuned the accommodations and selected the local guides, cruise ships, and trains. Until recently, he spent roughly 160 days on the road. Now he spends only 120 days a year traveling. Author Stephen Harrigan once called Emanuel when he was writing an article about homesickness. “I figured that since Victor traveled all the time all over the world he would have some interesting things to say about the affliction,” Harrigan said. “So I called and asked him, ‘Victor, how do you deal with homesickness?’ He paused for a moment and then said, ‘What are you talking about?’”

As a nod to the Houston nature club that played such a huge role in his life so many years ago, Emanuel has acted as a mentor over the years to dozens of kids, many of whom have pursued ornithology or related fields. Some of his closest friends are graduates of the children’s camps he created in Texas and southeastern Arizona’s Chiricahua Mountains. When I asked Emanuel’s friend Lee Walker, the former president of Dell, if Emanuel’s attention had had a big effect on children, he didn’t quite know how to answer the question. “I’m not sure when subtle becomes big,” said Walker. “I don’t think any child who is with Victor ever sees the world the same way again. Is that big or subtle?”

This past fall, Emanuel attended the fifty-third Freeport Christmas Bird Count, accompanied by two former Chiricahua campers. Barry Lyon, his 39-year-old assistant, was a camper in 1988 and later returned as a counselor; Cullen Hanks, a 35-year-old conservationist at Texas Parks and Wildlife, attended the camp as a teenager. A few hours into the day, when Hanks had gone to get the car, Emanuel and Lyon spotted a vermilion flycatcher. “Go get Cullen!” Emanuel said. Lyon walked out of the woods and down a road to summon Hanks. He returned a few minutes later, alone. “He doesn’t want to see it,” Lyon told Emanuel. “He doesn’t want to see it?” Emanuel said with mock incredulity. “Oh, Barry. We must not have done a very good job at camp.”

It is usually difficult for birders to articulate why birds are significant in their lives. For some, it is a way to heighten their awareness of seasons and geography, a way to connect them to nature. Others appreciate birds as a way to mark space apart from man-made signs and roads. Many simply find it relaxing. Everyone has a reason. “How do you explain what brings meaning to your life?” one birder asked me with a shrug.

Emanuel and I were walking around his neighborhood park one morning when he started talking about a duck called a bufflehead. “It has kind of a rounded head,” he said. “If you have a day like today, and you have the sun behind you and you’re close, you can see that it’s not black and white.” He waited a second for this to soak in. “The head is iridescent, and when the light hits it, it turns out to be the most incredible color of emerald, washed with maroon and gold.” He sounded amazed that something so wonderful existed. “It’s hidden beauty,” he said. “It’s like seeing deeper.”

Normally Emanuel scans the trees for movement, but now his gaze became distant. “My aunt Claudine Williams was one of the top businesswomen in Las Vegas,” he continued. “She was also the last surviving member of my parents’ generation. Everyone else had died. She didn’t have much longer, and I went to see her. We were sitting there, talking, and a caretaker approached me, and she said, ‘You can go for a walk. Someone else will be here soon.’ There was a golf course next to her house. All mowed grass. Just, you know, to a naturalist, boring. No vegetation other than short grass. No bushes. And then”—he stretched his arm in front of him, with his fingers spread wide—“I saw, on a pond in the golf course, up ahead, a bufflehead. I pulled out my binoculars, and I got really close. I could see all those colors, and I just focused on that and soaked it in. And it helped me deal with my aunt’s imminent death, the fact that I was seeing this bufflehead. It’s hard to explain, it really is.”

On a recent bright, 70-degree Saturday morning, Emanuel drove up to Hornsby Bend, the 1,200-acre sewage treatment plant in East Austin, to meet up with some of his young friends and their parents. Eliot Reynolds, age seven, exited his car with his mom and dad and looked at the large, flat fields dotted with ponds. Another vehicle holding three young children, ages four, five, and six, pulled up.

“It smells like poop around here,” said one young girl, stepping out of the van.

“That’s because there is poop around here,” said her dad.

“It used to be a lot worse, guys,” Emanuel said. He was already setting up his high-power scope to watch some ducks in a pond when his eye was drawn to movement near the shoreline. “Eliot! Where’s Eliot?” he called. “Eliot, take a look and see this bird. This is a really neat bird. It’s a kind of shorebird; it likes to be around water, and it’s white below and brown above. I want you to pick it out, Eliot, on the page.” He guided Eliot to the scope and riffled through his field guide until he got to a page featuring many birds that looked nearly identical. Eliot peered through the scope and focused.

“See it?” asked Emanuel.

Eliot looked carefully through the scope, then stood back and put his index finger firmly on one bird on the page.

“Killdeer!” Emanuel said. “You know why it’s called killdeer, Eliot? It’s because when it flies it says, ‘Killdeer! Killdeer! Killdeer!’ Oh, now it moved.”

Later in the day Emanuel would try to excite the kids by screaming when a spider descended on his head. He would tell them about the time he accidentally ate a stinkbug, thinking it was a berry. He’d look them in the eyes, just as he had Bush and Plimpton and Gell-Mann, and tell them a story about the caracara’s status in Mexican history. And his enthusiasm would be contagious enough that the earthy scent would go without comment for the remainder of the trip.

But for now he kept everyone focused on the killdeer. As he realigned his scope, he spoke with great excitement. “It lays its eggs next to the road sometimes, just on the bare ground. It doesn’t build a nest. I’ll show you in the book again. Show you in the book. Killdeer. Here it is. Here it is. Has orange on the tail. If you look at the tail. And right around the eye it has a red ring. You see it?” As Emanuel creased the binding, Eliot put his arm around Emanuel’s neck and watched curiously as the man examined the page and then looked up at the bird, possibly the 10,000th killdeer he had seen, awed, as if he had never seen anything so beautiful in all his life.