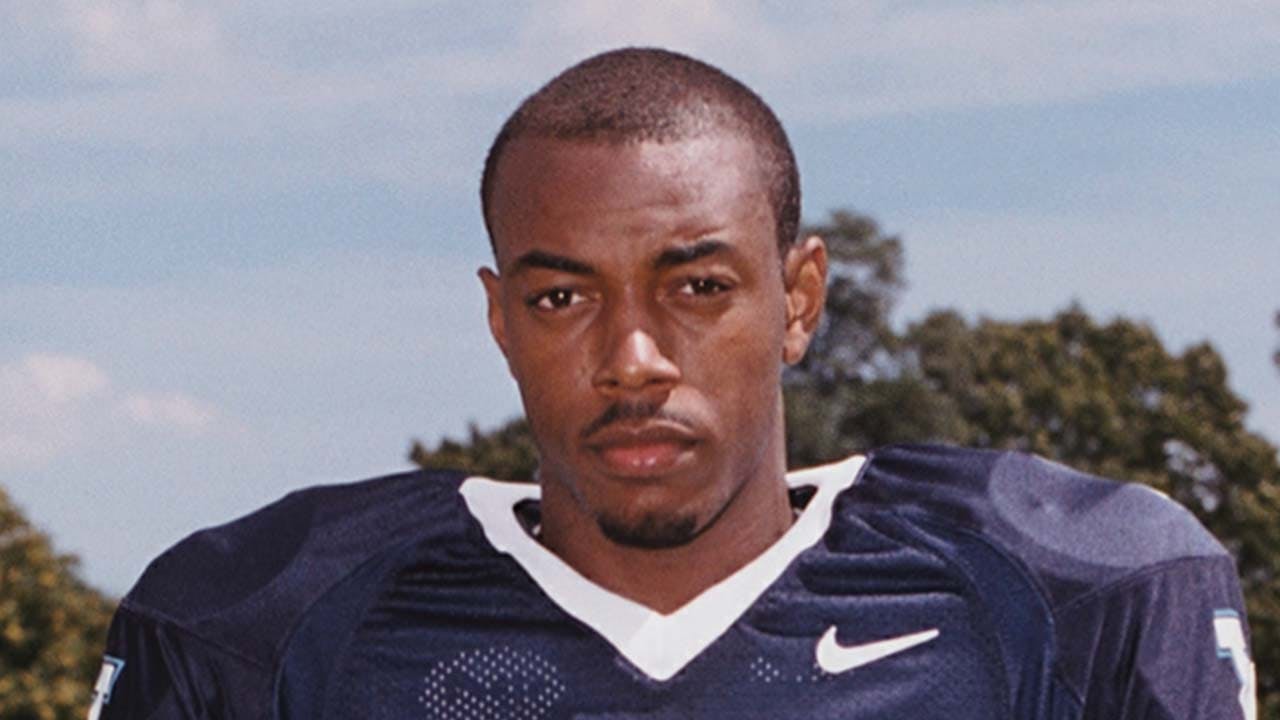

When Casey Gerald was growing up in Dallas’s poor South Oak Cliff neighborhood, he never imagined that someday he would give the commencement address at Harvard Business School, or that his speech exhorting his classmates to help make the world a better place would go viral on YouTube. Gerald, who is now 29 and lives in Brooklyn, had a tough upbringing; his parents abandoned him, and he was largely raised by his grandmothers and sister. Yet he persevered and was recruited to play football at Yale, from which he graduated with a degree in political science. A few years later, he enrolled at Harvard, where he and three classmates founded MBAs Across America, a nonprofit that sends MBA students across the country during the summer to give advice to small businesses in underserved places like Detroit, New Orleans, and rural Montana. This month, he will deliver a keynote address at SXSW Interactive.

Jeff Salamon: You went from a somewhat rough upbringing to Yale. What was that transition like for you?

Casey Gerald: My first year at Yale was one of the most difficult years of my life. I showed up with clothes two sizes too big and a coat two layers too thin and an accent that nobody could understand. I never realized how poor I was until I got to Yale. I had gotten what I thought was a good score on my standardized tests in high school. Then I got to Yale, and, you know, the dumbest people I met had scores that were way higher. So there was this whole world that I never imagined, never even knew existed. It was really quite terrible. But I was fortunate to have great friends on the football team, who became family for me. I wound up being transformed by my time at Yale.

JS: Was there something in particular that helped you get over the hump eventually?

CG: Well, actually there was an English teacher, Andrew Ehrgood, who was really the first person that made me feel like I had the chops to make it at Yale, the intellectual chops. That I could think and I could write and I could speak and my unique and particular view of the world was not so bizarre that it was not valuable. So there were people like him, people like my coach, Tony Reno, who didn’t show any pity on me for being this kid who felt like a fish out of water and pushed me to shape my unique outsider reality into something that had some meaning.

JS: So many people say that college athletics these days stand too far outside the general mission of the university, but it sounds like your experience was central to your education.

CG: The reality is that I wouldn’t have been at Yale if it weren’t for football. There’s no question about that. For all of the very reasonable and real critiques of the industry of college football, which I think has great challenges without question, the game of college football at its purest is something that is profoundly redemptive for people like me. I’m very grateful for it.

JS: I’m just curious. What did that English course with Andrew Ehrgood focus on?

CG: It was the intro English course basically. I remember so many things that we were trying to dig into, like debating Plato and Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. It was the first time I really grappled with the question of what are the underpinnings of what justice looks like for me and what it means for life to be shaped around justice in a very practical sense rather than just the philosophy of it.

JS: Between your junior and senior years, you were an intern at Lehman Brothers and you basically arrive there as the 158-year-old firm is melting down. That gave you a front-row seat at the worst financial calamity since the Great Depression. Can you tell me a little bit about what you saw when you were there?

CG: I’ll never forget, my first day they fired, I believe, around three thousand people. If it wasn’t that first day, it was that first week. I remember the second or third day of orientation the chief operating officer came in and he said, in essence, “Listen, this is a cyclical business. We’ve been here before. The fundamentals are strong. Lehman is a great firm. We’ve been through things before. We’ll be fine.” About a week and a half later he resigned.

I was there when I think they changed the compensation structure for senior executives, like managing directors, and made it far more based on stocks than on cash. As interns, we were so deathly afraid of managing directors, they were kind of like Voldemort. They came back from this meeting and you could tell they were so unnerved. I could imagine them saying, “What in the world are we going to do with this stock that is going to be worthless?” So there was anxiety, far more anxiety on the part of the senior people than the junior people, because we just—and I can only speak for myself—never really imagined that the firm would go out of business. That was not really an option that was on the table.

JS: What did you take away from that experience?

CG: I took a couple things away from it. One, I always had this view, growing up, that, as my friends and I would say, they say money can’t buy you happiness, but nine times out of ten all our problems are because we don’t have any money. So I wasn’t an altruistic person; I just didn’t want to be poor anymore. And that summer, I remember feeling that I really made it, that I would never be poor again; I started getting these checks that were very large. My grandmother cleaned houses to help us survive, and she was a very dignified woman, did very dignified work. So I never really knew that people could make this much money. And I also never anticipated that it would feel so empty, that money actually was such an impotent source of meaning for me. That’s one thing I took away from that summer. I think the other thing, the more macro takeaway, was that anything is possible. That the things and the institutions and the promises and agreements that I took for granted could disappear. That’s a very radical shock. It was sort of, in some ways, the continual thread of my generation. We were in high school when 9/11 happened. None of us were raised in the nineties feeling that anything like that would ever happen. None of us really thought that something like Lehman Brothers and the financial crisis could happen. I think it was really a crisis of belief in a way.

JS: After you graduated from Yale, you worked in Washington, D.C., for a while, and then you come back to Texas in 2010 and worked on Bill White’s gubernatorial campaign, which didn’t turn out so well. What was that experience like for you?

CG: Listen, I was a very junior volunteer. I wasn’t like some senior honcho. And I just knew for sure that Bill White was going to be our next governor. He seems to be a decent human being. He seems to have done great work. He seems to be reasonable. I thought a state like Texas was really going to be on the frontline with a lot of issues the country was facing. So I remember going into the night of the election and I was very hopeful. And then the returns started coming in. And I’ll never forget, I think it was David Dewhurst—it was one of the senior Republicans who won that night—and he said something to the effect of “This was a conservative year for a conservative state. And what happened, the thing that we thought would happen, happened.” This is what this person said, and I think he was right. So it was a great education for me that I really didn’t know the slightest thing about Texas politics and that my hopeful naiveté was quite misplaced.

JS: Did it sour you on politics at all?

CG: No, I wouldn’t say that.

JS: So then you move on to Harvard Business School, and you’re there with people who are probably going to be running the biggest companies in the world someday. What sort of people did you think your classmates would be?

CG: I thought they’d be the folks that I had worked with on Wall Street. I thought they’d be pretty straitlaced folks who wanted to be dedicated to business as usual.

JS: What surprised you when you actually met them and spent time with them?

CG: People have this sense that HBS is this cutthroat, dog-eat-dog competition of people who are just ruthless. And that wasn’t the case at all. I found people who I consider today not just friends but family. And they were people who, much like many people in my generation, have a deep hunger for a life of purpose and a life of meaning. And I don’t mean just folks who want to go work in a nonprofit. I mean folks who were passionate about working at a hedge fund industry. Or in consulting. They all had their reasons for doing those things. I went to business school with the former captain of the U.S. Olympic hockey team, you know? I went to business school with the former drummer for M.I.A. I went to business school with folks who had these really magical stories and who were looking to this experience not just to make a lot of money, although there were plenty of people looking to it for that. But some people, at least a critical minority of people, were looking at it as an opportunity to ground themselves in some journey to a unique life and a life of purpose.

JS: Your Harvard commencement speech was pretty idealistic for a business school.

CG: Well, I push against the idea that it was an idealistic speech. If there’s one line I want people to take away from that speech, it is “We have more work to do.” And I hope people take away the Faulkner quote [what follows is a paraphrase of a passage from William Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel acceptance speech]: If we don’t do this work, if we don’t do these things, then we live not with love but with lust. We work for defeat, in which nobody loses anything of value, right? For victories without hope, and worst of all, without pity or compassion. We grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars.

I didn’t give the speech feeling that everybody was on the same wavelength. I didn’t give the speech feeling that everybody would agree. I didn’t give the speech feeling that I, or everybody, would live up to the ideas that I was articulating, which is why I say, “hard work, thriving work, work that may defeat us,” right? We might not succeed. What I tried to do was to clarify the terms of debate for this generation of people engaged in business. And to the extent that people were not living the life that I painted in the speech, that’s okay, right? Because even I haven’t lived that life. There are many days that I fall short and that we all fall short. But we cannot afford to not try to use our lives in some way that tackles the great challenges that we face. And that’s not to say that we are going to be perfect. That’s not to say that we all are going to change the world, or that we even know what changing the world means necessarily. But it is to say that the idea that we came here just to get a lot of power and get a lot of money ain’t gonna cut it. And that’s something I have to tell myself and that’s something that hopefully my friends that went to school with me received, from a place not of judgment but in some ways of commiseration, and an invitation for our lives to mean something more.

JS: It looked like you did that speech with virtually no notes. How did you learn to give a speech like that?

CG: Oh, you know, I started giving speeches for Easter in church when I was five or six years old. I was taught how to speak by the old women who raised me. My fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Davis, forced me to do an oratorical competition, and other women in the community would bring me into their living rooms and they would make me rehearse these speeches over and over and over and over again until they were satisfied. And there was never an excuse for forgetting things; there was never an excuse for not articulating things properly. Most of the things that I learned that shape who I am now, I learned long before I got to any place like Yale or Harvard. I learned from people who may not have even had a college education, but they taught me so much about what it meant to really do the work of not just writing a speech but also giving a speech in a way that people can hear.

JS: So was that a speech that you wrote out and then memorized? What’s your process for something like that?

CG: First I had to figure out what the message is. That’s often the most difficult thing because, partially, I’m a bit of a mystic in that I am listening for the message to come. And so, the very kernel of that speech— I didn’t have it. I had writer’s block. And I was sitting in a café in Cambridge over spring break, and I was working with Marshall Ganz, who is a professor at the Kennedy School. He has this thing called “public narrative,” this idea that each one of us has a story of self, a story of us that kind of shapes who we are. And for the story of self, he has a worksheet that folks can use. And I thought it was kind of new age–y, so I was skeptical. ButI was desperate, so I figured I would do it. So I sit down and it says, “Write out the one or two experiences that have shaped you and why you do what you do.” And so I’m sitting there, and it tells you, “Give us details. Don’t be vague about it.” So I’m sitting there, and the first thing that comes to mind is the experience of being held at gunpoint that starts the speech. And I really hadn’t talked about that with very many people, and I really hadn’t dealt with it myself. Before I got a sentence out on a sheet of paper, I broke down crying there in the middle of that cafe, and it was very embarrassing, you know, to be crying, especially because I’m not a very big crier. But I knew that that was the speech. Not because I had anything I needed to say to somebody, but because I needed to figure something out for myself. So the kernel of this speech started off with just trying to figure out where this story would take me if I dug into it. I write longhand on legal pads because I feel like I think better that way. Also, when I was first doing speeches, I didn’t have a computer, so I had to write them out. So anyway, I write out four, five, maybe six drafts longhand until I get comfortable with the idea. Then I go and type it, and by the time you type something after you’ve written it a lot, you’ve kind of already paid the price to remember quite a bit. And then there’s the layer of revision that is conceptual: Does this idea work? And a lot of times I send it out to people. So I sent it to this guy, I remember, who had won the Profiles in Courage Award. And that line—“Now I see the biggest sign for hope: you my friends, my fellow graduates, not because of what we’ve done, but because we have more work to do.” That was the final version. In the first version it didn’t say “not because of what we’ve done, but because we have more work to do.” It was basically saying, “You are the greatest sign for hope. Period.” And this guy said, “You’re letting people off of the hook. This idea doesn’t work; this concept is lazy.”

There’s a level of work that takes some time and is often done in conversation with other people—the level of trying to get the ideas and the concept right. It takes somewhat of a thick skin.

The other layer of revision is at the level of language. And a lot of times the language revision work is in conversation with people who are dead. When I’m thinking about words, I’m thinking about language from James Baldwin, I’m thinking about language from Walt Whitman. I’m thinking about that great line in the Aeneid: “For years they wandered as their destiny drove them on from one sea to the next: so hard and huge a task it was to found the Roman people.” This rhythm and cadence and language are things that often were written by people who have been dead for a long time. And that’s typically where I look to try to get the language right and get the rhythm right.

JS: At times that speech felt like a sermon, though there was little or no religious content. It strikes me that that’s something Obama does. Have you learned anything from watching him talk?

CG: President Obama is a fantastic speaker. But I think the people I tried to steal from earliest were Martin Luther King and Jack Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy. I think Dr. King was extraordinary at appropriating language. He took language from one world and moved it into another. And I think that actually is in many ways just the magic of the black tradition, right? You know, blues is brilliant in a lot of ways because it’s appropriating a groove, it’s appropriating a language, typically from the context of religion, the Christian religion. That’s what I really take from Martin Luther King, that’s what I took in my early teens and twenties.

JFK was brilliant at the structure of the language. There was almost a march to JFK. He was great at “Not because, but because,” “Not this, but that.” And there’s a sort of rhythm that comes from that, that is very powerful. He used to do this thing where he would point his finger at people, and he was pointing, I think, not to actually point at people but to punctuate the language. I think that was what I took from JFK.

Bobby was brilliant in that he had a very subtle way of introducing images—he was very understated. He could introduce other people into his speeches, he could introduce Aeschylus, he could introduce Shakespeare, and he could do it in a way that didn’t make him sound like a pompous jerk. I think that that’s a great creed of language.

So, I honestly haven’t taken very much from President Obama, although he’s an extraordinary speaker, mainly because I take most of my cues from people who are dead.

JS: So let’s skip to MBAs Across America. Can you tell me one success story from MBAs Across America that you’re really proud of?

CG: The first one. We showed up in Detroit in the summer of 2013 having no idea how this thing was going to go. It was the week the city went bankrupt and our first entrepreneur was a guy named Sebastian Jackson. He ran a barbershop called the Social Club Grooming Company, which at the time was recycling hair from clients to accelerate compost and plant trees in some of Detroit’s most blighted neighborhoods. Sebastian was looking at the barbershop as a powerful epicenter for revitalizing Detroit. So we got there, we worked with him for a week, and we helped him recruit a new team of stylists. We helped him build his first PRN system [a PRN is a Packaging Recovery Note, a document that demonstrates that waste-packaging material has been recycled into something new], which literally was a Google Doc that we put on his iPad. And then we connected him to folks in our network, because we found that many entrepreneurs were really going it alone in ways that we felt they shouldn’t have to. So we were there for a week, and Sebastian called us few months later and says, “When you got here, I was on track to do six thousand dollars of revenue a month. Now I’m on track to do eighteen thousand dollars. I raised about one hundred thousand dollars from a local investor because you helped articulate my business plan for the first time. And the guy you connected me to, this community organizer in Detroit, we partnered and tore down an abandoned home in Detroit and used the wood to renovate the barbershop.” So by the time we went back, the Social Club looked totally different than it did when we first got there, and since then we’ve sent teams back to Sebastian, and the Social Club has continued to grow. Sebastian was part of a reality television series we did with Headline News called Growing America and the message and the takeaway that we got from our work with Sebastian and why it is a success story is not the idea that all the helpless people of America needed was to be bequeathed with more Harvard MBAs. That wasn’t the message at all. It was that there were extraordinary people like Sebastian working all over the country and doing great things and all they needed was a little wind at their backs, and that was very life changing for us.

JS: Have you had any frustrations doing this project?

CG: Oh, so many frustrations. I think the great personal frustration for me has been probably the frustration felt by anybody that has something that they fundamentally believe in that they feel that they’re making a sacrifice to bring to fruition, and that’s the frustration of people not buying in quickly enough. There were so many people who said, “Well, there’s nothing that you can really do in a week to help an entrepreneur.” Or they’d say, “Well, you know, how is this really going to give me a job?” Or they’d say, “Well, you know, how is this going to be sustainable? You can’t just keep coming back and asking donors to give you a check. I mean, how you gonna make it sustainable?” So I think the frustration was that the truth wasn’t always as self-evident to other people as it was to me. Which I think is a good frustration to have, to be honest, because it pushed me and it pushed all of us to really think hard and long about what we really believed and how we could get the world that we wanted to see here more quickly.

JS: During the summers, you run MBAs Across America. What do you do the rest of the year?

CG: A lot of the year was built around recruiting MBAs, recruiting entrepreneurs, choosing a selection of teams we put on the road and executing that over the course of the summer. About a year ago we launched an initiative to take our model and put it into business schools, like Harvard. So we actually helped create a course at Harvard Business School this past fall that is basically taking this model of getting MBAs to work with mission-driven small-business owners and communities and making it part of business school curriculum. That yearlong course is now running at HBS. And right now we are in the process of doing something radical—we are putting the organization out of business and making the model fully open-source for folks to use themselves.

JS: You’re shutting down MBAs Across America? Effective when?

CG: By the time I speak at SXSW it will be out of business.

JS: Why?

CG: One reason is the “theory of change” idea, which is that we don’t need permission from a central authority to solve the challenges that we see. What happened over the course of three years is that people went from ruthlessly doubting us to blindly believing we were saviors. We had MBAs who felt that the only way they could do this work was to be accepted to our program and entrepreneurs who felt that the only way they could get support was if MBAs Across America existed. And I think one of the big lessons of our generation has been that it’s a very dangerous thing to put all our faith in a savior who’s going to solve all our problems. We’ve spent the past three years seeing lots of unconscionable realities in America, things that we often think might be solved by a successful nonprofit or a charismatic entrepreneur. But I’ve come to believe that we need urgent, systemic, and fundamental change in order to deliver on the promise of America, that everybody will have a shot. So by shutting down a successful organization, I’m hoping to spark a conversation about that larger work that needs to happen.

JS: So what’s next for you?

CG: Well, the first thing that’s next is to try to give a message that actually means something to people. I don’t really see speaking at SXSW and speaking at TED in Vancouver next month as something I do as a job or something I do as sort of a side project. Maybe it’s because my grandfather was a Baptist preacher for fifty years, but I do see it in a lot of ways as a ministry and that’s not about a religious evangelical ministry or anything like that. It’s important for me to articulate to people what the past three years—and the past almost thirty years—of my life mean for the moment we’re in right now. Not as a gospel that people need to adopt for themselves but as the testimony of one person who is trying to use his life in a way that has some purpose. So I want to focus on giving talks. And I’m working on a book project. Then, we’ll see from there.

JS: Do you have a book contract?

CG: I am finishing the proposal in the next week and a half. So hopefully I will have a book contract by the time March is done.

JS: You give a lot of talks—it must be tough to generate inspiration on demand. Do you ever find yourself running on autopilot?

CG: I’m often tired and uncertain. Afraid that people don’t really want to hear what I have to say. Or they do want to hear what I have to say so they can continue to disagree. I have a great number of uncertainties. The speech I gave at Harvard changed my life, but not because of all the things that happened after the speech. The morning of the speech, I woke up and all hell broke loose. It was the coldest day in May in the history of Boston. It was raining, and this was an outside ceremony. I had maybe two or three hours of sleep the night before, and my last run-through had been a complete disaster. I was forgetting sections, and so I’d lock myself up in this office room to try to compose myself. I was just so anxious. At 8:30 that morning, somebody called me and told me Maya Angelou had died. I had never met Maya, but she was my patron saint in some ways. I’m falling apart, I’m having these crying spells and losing it. So at 9 I call my grandmother, and I said, “Granny, would you pray for me real quick?” My grandmother was a bit of prayer fascist; if you had dropped a cup, you know, she’d pray over it. So I knew she would pray. I’ve heard her pray so many times I thought I knew what she’d say. But she prayed this prayer that totally changed my life. She said, “God, will you help Casey remove self, so that whatever it is that you have to say to people, they can receive it? Because there are a lot of cultures but there is only one mankind and all of them can hear you if he gets out of the way.”

It was like stepping out of the Matrix. I had never really understood what it meant to be a vessel. I had never really understood how much my ego had gotten in the way of so many things that I had done. So that speech, and everything that I’ve done since then, has been grounded in this idea that it’s not about me. That my real task is to get out of the way, to get my ego out of the way, to get myself out of the way, and to try to connect with people, so that whatever it is that needs to be said to them, whatever it is that they need to receive, whatever it is that I am there to do can be done despite my weakness, despite my frailty, despite my uncertainties, despite my ego, or anything else.

JS: One thing I heard you say in an interview is that you get strength from vulnerability. And that sounded to me like you’ve been listening to your fellow Texan, fellow SXSW keynote speaker Brené Brown [the best-selling Houston-based researcher and self-help author]—did I catch that reference correctly or no?

CG: I didn’t take that from Brené, although I think that she is incredible and I’m so glad that she’s going to be at SXSW. I’ll tell you where I got that from: I’m part of a leadership group, and my first time going to the annual summit, this woman, Najeeva, who is an Islamic leader, said, “Let’s stop pretending that we’re all okay, because our beauty is in our brokenness.” And I might have been about 24 at the time, and that simple phrase really solidified that I had spent so much of my life ignoring my traumas, and what I found is that when I’m honest about the stuff I’m going through, or my failings, my weaknesses, my fears, et cetera, is that it creates space for me to grow and for me to heal, but also for other people to be honest as well. I think the reality is that we’re all a mess at times. I found that the strength from vulnerability is partially grounded in the fact that there’s little strength in lying, and to say that we’re all not vulnerable, to say that we have not been hurt and to say that we are pure and perfect beings, is just a flat-out lie. There’s no strength in that.

JS: If I read your Twitter stream correctly, you spent New Year’s by yourself in Possum Kingdom State Park—is that right?

CG: I went down for a week in Possum Kingdom that included New Year’s because I needed to isolate myself and work; I needed to write. And I felt like doing it there. It would be a lot more productive than doing it in New York. It was actually far more transformational than I anticipated.

JS: How so?

CG: In two ways. One, you can look at the past ten years of my life and interpret it as me running away from home—including living in New York now. Maya Angelou used to say, home is underneath your fingernails. It’s in between your teeth. It’s in the way you walk. The reality is that my family has been in Texas since before the Civil War, and it’s my home. It has shaped me in ways—physical, mental, emotional, spiritual—that I may not ever know, and I hope to know more. And what I found is that coming back and trying to write in Texas really gave me space to tap into the unique voice and independent voice that Texas has given me. And being in New York all the time, meeting with people in New York, and in places like Yale and Harvard, and all these other places, there’s actually a lot of groupthink that ends up happening. You have to comport yourself in a certain way, and certain sayings just don’t make any sense, certain references don’t make any sense. But coming home, I found I was able to access, I think, a certain source of freedom and independence, and also irreverence.

The other way it was transformational was that, you know, I’m in transition from being an entrepreneur to being a writer, and that’s a very hard transition. Primarily because I used to always think, when somebody says, “When do you write?” I said, “Well, I write either when I’m panicked or I write when I’m inspired.” And the reality is that the only way you’re a writer is if you get up and write every day, regardless of how you feel. So that weekend in Possum Kingdom, when there was practically nothing else to do, really gave me the space to sort of step into, not necessarily a new identity per se but into more of an understanding of the work that I’m doing now that is very helpful that I wouldn’t have been able to do with the distractions and excuses of being in New York.

JS: You had another tweet that said, “Everything that’s not essential needs to go.” What have you gotten rid of lately that wasn’t essential?

CG: Oh, boy. Well, the most acceptable answer is, I got rid of a lot of people. I got rid of a lot of draws on my time. I got rid of some projects that I was considering that I didn’t feel were going to be projects that I would look back on and say, “You know, I really believed in that.” I think the biggest thing I’ve tried to get rid of is fear. Mostly the things that are not essential but that are in my life and have been there because I was afraid. Projects I’ve worked on because I was afraid that not doing it would hurt my career, or hurt my bank account. People that I kept in my life, despite the toxicity, because I felt that I was afraid of not having certain connections. Ideas of myself that I held onto, like, if I wasn’t the CEO of an organization, I wouldn’t have any value in the world. I think fear is the enemy and fear leads me, and I think a lot of us, to imprisoning delusions. So there’s a whole host of things, from things that were on my calendar, in my inbox, things that were in my life that I had to get rid of as I’ve more broadly tried to get rid of fear.

JS: From the stuff I’ve read, the speeches I’ve watched, you tend to not put race really front and center. But when an African American guy is talking about inequality and making business more socially responsible, it’s almost automatically implied, at least for a lot of people listening to you. But you comment on issues from very much within the system. And right now we’re living in a real protest moment, thanks to Black Lives Matter, and all the campus activity that’s going on. What’s your relationship toward those movements?

CG: I have good friends who are leaders in the Black Lives Matter movement. I have good friends who run programs in the federal government. I have great friends who are raising money for Bernie Sanders, and I have great friends who are raising a lot of money for Ted Cruz. So I think my relationship to the people and all of these spaces really reflects my relationship to the moment that we are in, which is that the current state of our country is intolerable, and if this is gonna change, then it’s gonna take a hell of a lot of people to change it. It’s gonna take a hell of a lot of people who most likely have disagreed deeply with each other over the course of a long period of time. It’s gonna take a hell of a lot of people who, in the history of our country, have been at each other’s throats. And it might take ideas and approaches that we would have never considered before. So I’m in league and solidarity with anybody who is trying to dedicate their time to ending injustice in this country, to ending the suffering of people—not just black people, but ending the suffering of people in this country and around the world. I’m in solidarity with people who are trying to make the idea of America something that is real. It’s a great idea, and we haven’t executed it yet, and I think people in our generation are tasked in a unique way to reimagine and to make the sacrifices, to reconstitute the way the country works. I have deep respect for the work people in movements like Black Lives Matter and in movements across the board that are raising a different consciousness in this country that are leading to real action to make this country’s promise real.

JS: You said something earlier in our conversation that one thing we’ve learned is to try to not put a lot of hope in one savior. Were you referring to people putting hope in Obama eight years ago?

CG: Yes. And I am referring to the hopes people put in me. I was a young staffer in Washington, D.C., who went to Washington, D.C., because I had a view that Obama was our generation’s Jack Kennedy, and many of us were deeply disappointed. We were very angry and very hurt. And we felt he had let us down. I think the reality eight years later is, we’ve grown up. We probably had unrealistic views of what any one person could do, even if they were president of the United States. And so in that way I think having a president who is such a decent man, who means so well for the country, whether you agree with him or not—and of course there are great critiques you can make—the reality is that we have learned that change does not happen just because some really awesome guy shows up one day. That’s just not how it works.

JS: Oak Cliff, where you grew up, is now prospering and gentrifying thanks to the Bishop Arts District. How do you feel about what’s happening to your old neighborhood?

CG: Well, to be honest with you, the Bishop Arts District is not my old neighborhood, and my old neighborhood is not gentrifying as far as I know. So what’s happening in Bishop Arts—look, I don’t live in Dallas, I don’t pay taxes in Dallas, so I can’t say anything about it. But I would not take what’s happening in Bishop Arts, I would not take any gentrification or prospering that is happening and maybe happening in Bishop Arts as a sign that things in Singing Hills or in Beckley or in Highland Hills are changing in any deeply structural or material way.

JS: Last question: I know you’re a big Cowboys fan. Any comment on this past season?

CG: “No. [Laughs.] The Cowboys break my heart. I was raised in a generation of Dallasites—a generation of Texans, a generation of people who love playing football—who took it as an annual expectation that the Cowboys would, if not win in the Super Bowl, if not play in the Super Bowl, at least contend for the Super Bowl. This was as certain for us kids as the fact that Christmas was gonna come and we would have to go to church for Easter. To be honest with you, it’s a very depressing thing.

To meet kids from Dallas who have never witnessed a Dallas Cowboys Super Bowl, I think it’s a real tragedy—a national tragedy, even a global tragedy.”

JS: Do you think it will change?

CG: Oh, I have no idea. I sure hope they do. I don’t see any signs at the moment that we’ll be in the Super Bowl anytime soon. But I hope I’m proven wrong.