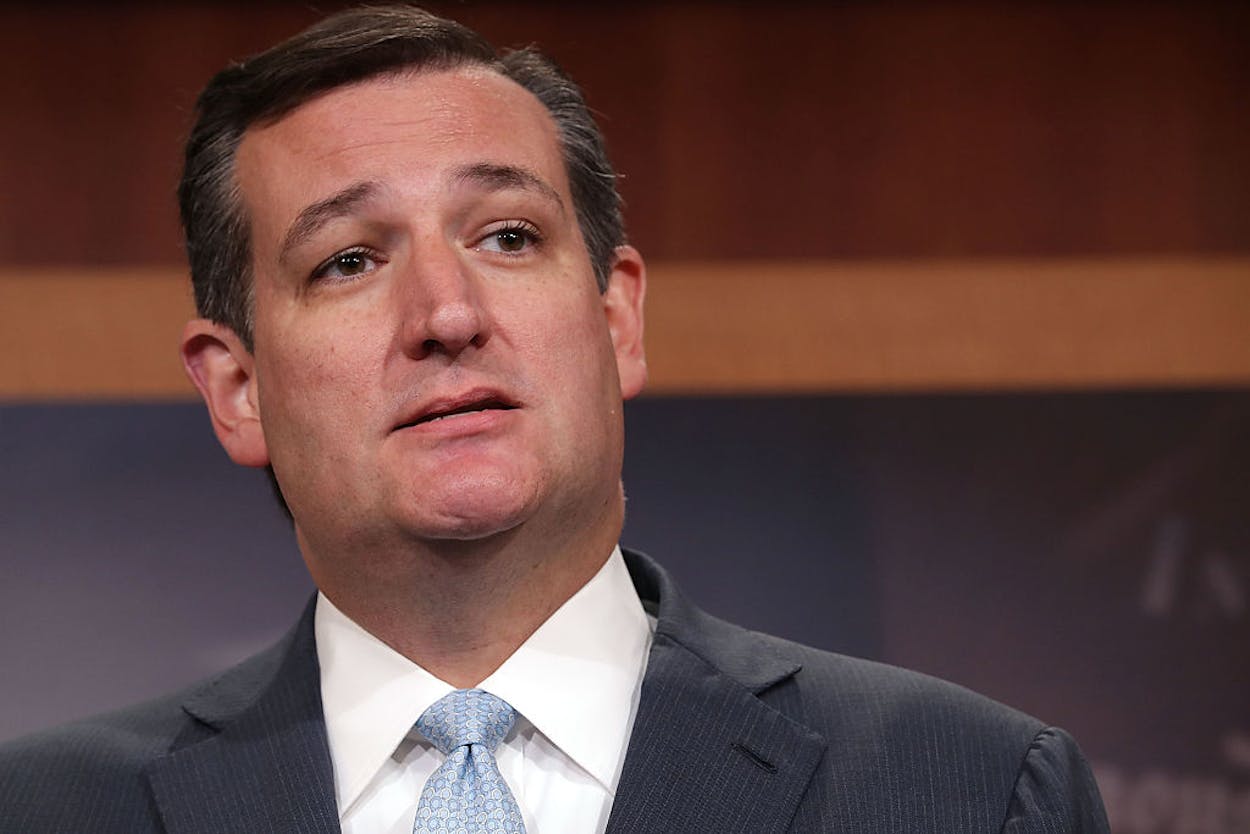

The U.S. Senate voted on Thursday to nix Obama-era regulations that required internet service providers (ISPs) to get your permission before they track and sell your data to third parties. The resolution was headlined by Arizona Senator Jeff Flake and was co-sponsored by two dozen other Republicans, including high-profile conservatives like Marco Rubio, Mitch McConnell, Rand Paul, and Texas Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz.

This resolution would essentially turn your web browsing history, in all of its naked shame, into a package to be sold and distributed. For example, let’s say Cruz Googled “Campbell’s Chunky Soup” 43 times over the weekend. Under the resolution he supported, his ISP would be able to sell that data in the corporate world without notifying him. Next time Cruz fires up Internet Explorer, he’d likely be inundated with ads for Campbell’s Chunky Soup.

But this runs deeper than soup. As the digital civil liberties non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation explained in a blog post, allowing ISPs to collect and store large amounts of personal data would potentially make it vulnerable to hackers. “Imagine what could happen if hackers decided to target the treasure trove of personal information Internet providers start collecting,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation writes. “People’s personal browsing history and records of their location could easily become the target of foreign hackers who want to embarrass or blackmail politicians or celebrities.”

In a statement sent from Cruz’s office to Austin ABC affiliate KVUE, the senator said that the FCC rules were federal overreach. “The rule that was overturned [Thursday] passed the FCC by a 3-2 vote ten days before the November elections despite strenuous objections from throughout the Internet community,” the statement said. “It was a clear-cut case of federal government overreach that harms consumers. Sen. Cruz cosponsored this resolution, and was grateful to see it passed by the Senate because the FCC’s proposed ‘privacy’ rules would have severely restricted small businesses, disadvantaged low-income consumers, encouraged disparate treatment of Internet Service Providers and effectively chilled free speech.”

Cornyn argued on the Senate floor before the vote that the FCC regulations “hurt job creators and stifle economic growth,” according to ArsTechnica. As Vocativ notes, Cornyn received nearly $160,000 in political contributions from Internet service providers since 2012, more money than any other senator who supported the resolution. Cruz, meanwhile, took in more than $115,000 from Internet service providers over the same span. The biggest donors were AT&T ($57,000 to Cornyn; $45,500 to Cruz), Verizon ($40,500 to Cornyn; $21,200 to Cruz), and Comcast ($20,300 to Cornyn; $32,800 to Cruz).

The vote was quickly condemned by civil rights advocates. “It is extremely disappointing that the Senate voted… to sacrifice the privacy rights of Americans in the interest of protecting the profits of major internet companies, including Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon,” ACLU Legislative Counsel Neema Singh Guliani said in a statement after the vote. “The resolution would undo privacy rules that ensure consumers control how their most sensitive information is used. The House must now stop this resolution from moving forward and stand up for our privacy rights.”

“These were the strongest online privacy rules to date, and this vote is a huge step backwards in consumer protection writ large,” Dallas Harris, a policy fellow for the consumer group Public Knowledge, told the New York Times. “The rules asked that when things were sensitive, an internet service provider asked permission first before collecting. That’s not a lot to ask.”

The Senate vote squeaked by along party lines, 50-48. It’s unclear when the House will vote or which way the vote will go, but if it does ultimately pass and the FCC rules are eliminated, then there’s no going back. Republicans are employing the Congressional Review Act in an attempt to vote away the regulations, and under that act, the FCC would be prohibited from implementing similar control in the future.