If you want to make your vote count in Texas in 2022, you should vote in the March 1 primary. Here’s why: the general election in November—the one that pits Republicans against Democrats—will likely be the least competitive in a long time, at least when it comes to congressional and statehouse races. The candidates who prevail in the primary will by and large be shoo-ins in the fall. The culprit is gerrymandering.

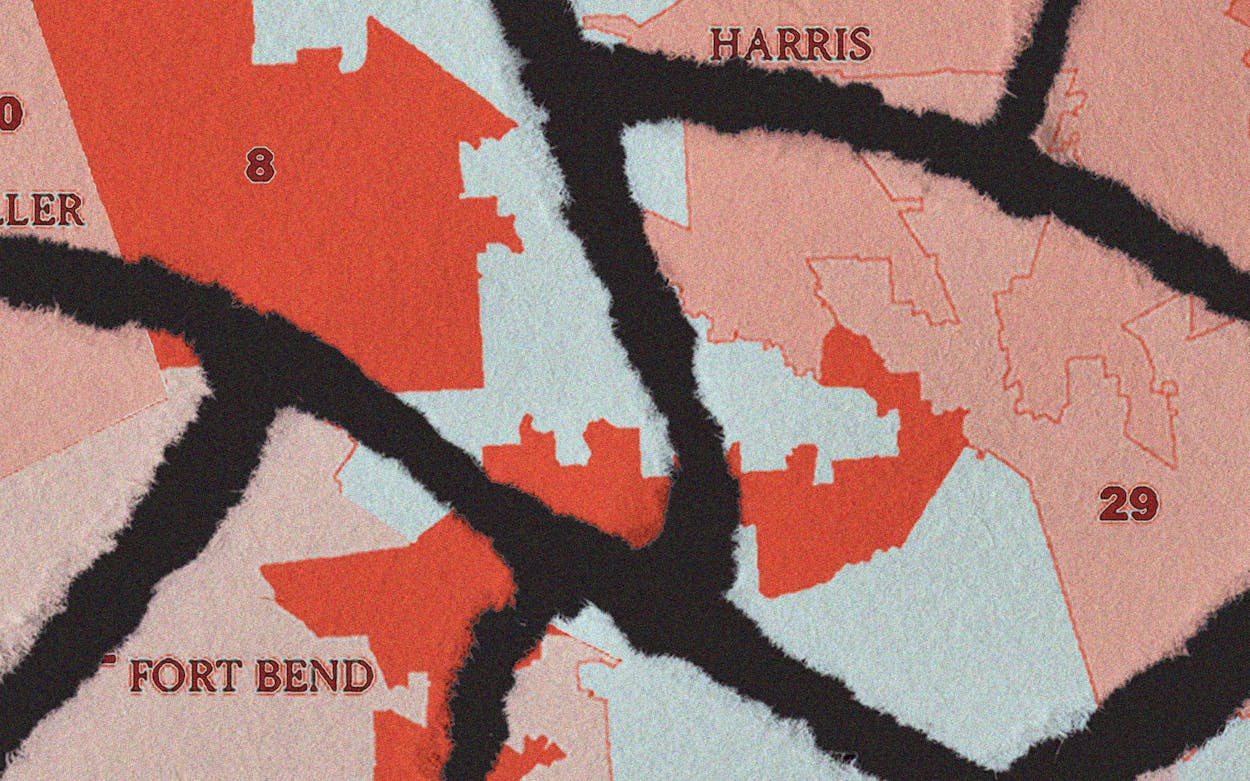

New district maps drawn by Republicans in the Texas Legislature last year have dramatically reduced the number of congressional and statehouse districts in which both the Republican and Democratic candidates have a plausible shot at winning. The congressional gerrymander is the most extreme. Almost every U.S. House seat in Texas is now so partisan—either extremely Democratic or extremely Republican—that there is little to no chance of it changing hands any time soon. Out of Texas’s 38 congressional districts, only one is considered highly competitive according to the polling gurus at FiveThirtyEight. That’s compared with 6 in 2018. So unless you live in the Fifteenth Congressional District, a fajita-shaped district that stretches several hundred miles from east of San Antonio down to the Rio Grande Valley and which Trump would have won by only 2.8 points had it existed in 2020, November is going to be pretty undramatic.

Barring a surprising upset, next year’s congressional delegation from Texas will consist of 24 Republicans and 13 Democrats (plus whoever wins the Fifteenth). That proportion is unlikely to change over the next few cycles, unless the courts agree with voting rights groups and Democratic officials that have sued over the maps (such cases won’t be resolved in time for the 2022 general election). In 2020, there were 11 super-Trump districts, where the former president won by fifteen points or more; under the new map, there are 21 such districts. The number of super-Biden districts went from eight to twelve. Only 3 districts, including CD-15, would have been within ten points.

The Texas House will also see fewer competitive races in the fall, compared with previous cycles. The number of races in 2020 in which the winner was separated from the loser by fewer than five percentage points was sixteen; under the 2022 maps, the number would have been nine. Consider that in context: there are 150 seats in the Texas House, so only 6 percent are competitive. The House map would no doubt have been even more extreme but for the so-called county-line rule, a requirement in the state constitution that prevents gerrymandering legislators from chopping up populous urban and suburban counties into multiple pieces and pairing them with their rural neighbors.

This is all, of course, by design. Redistricting in Texas is inherently partisan. Nobody expected Republicans, who control both chambers of the Legislature, to produce maps that were fair to Democrats. But with few remaining legal restraints after the Supreme Court gutted parts of the Voting Rights Act over the past decade, Republican mapmakers were able to cook up some of the most extreme gerrymanders in the nation. By and large, the new districts were drawn up to protect Republican incumbents. The mapmakers worked their magic through the dark arts of “packing” and “cracking”—either packing Democratic voters into already heavily Democratic districts, or cracking minority communities, splitting them up and then pairing them with white, mostly rural swaths of the state. Rather than make a play for Democratic-leaning constituencies by drawing at least somewhat competitive districts, as they had done in 2011, the architects of redistricting in 2021 played defense. They opted to retreat to political safe spaces.

“Republicans perceive they’re potentially at the tipping point and that scares them,” said Michael Li, a lawyer who grew up in Texas and now serves as senior counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonprofit law and policy institute at New York University. “There’s a lot of Republican bravado about we’re going to win back the suburbs, we’re going to start winning Latino voters, but they didn’t draw maps like that, with the exception of [CD-15]. It’s like they looked in the mirror, saw the future, and were deeply frightened about what the future would be.”

Between 2010 and 2020, the Texas population grew by 16 percent, from 25 million to 29 million—with Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations contributing 95 percent of that growth. But the new maps, drawn up with Cartesian precision, radically dilute the political power of non-Hispanic white Texans. Both of the new U.S. House districts Texas gained because of its growth were drawn for a non-Hispanic white majority. The number of new congressional districts where non-Hispanic white Texans constitute a majority is 25—or about 66 percent of the total—despite that group representing only 40 percent of the state’s population. In lawsuits pending in federal court, plaintiffs argue that the maps were drawn to thwart the political power of racial minorities in violation of federal voting rights laws.

Critics have largely focused on the racialized nature of the new maps, but they also threaten democracy for everyone. What’s the point of elections if there are few real choices on the ballot? Why should voters bother to go to the polls, at least during general elections, if the outcome has already been decided? Sure, even an independent commission drawing up maps based on considerations other than partisan gain will come up with some very red and very blue districts, a reflection of how we’ve sorted ourselves geographically. Under “fair” maps, Lubbock isn’t going to elect a Democrat to Congress, and Austin isn’t going to send a Republican to Congress or the state Senate. But Texas is filled with communities that are mixed—economically, politically, racially, and otherwise. Why shouldn’t both parties have to compete for the votes of variegated, diverse Texas? Why shouldn’t candidates have to appeal to a broad swatch of the populace, rather than their most fervent base supporters?

This brings us back to where we started: with the importance of the primaries. It’s long been a fact of political life in Texas that the GOP primary is the most important election on the calendar. Democrats haven’t won a statewide race in the past 27 years and haven’t controlled either chamber of the Legislature since 2002. The real statewide contests happen in the spring, during the GOP primary, when a tiny sliver of Republican voters gets to pick the state’s governance team.

Typically, no more than a quarter of the state’s registered voters go to the polls for the primary. On the GOP side, as few as 10 percent participate. When races go to runoffs, the numbers are even lower: In 2014, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and Attorney General Ken Paxton prevailed in an election in which only 5.5 percent of registered voters participated. Ted Cruz won his runoff to take his seat in the U.S. Senate by persuading just 4.8 percent of Texas’s registered voters to give him their vote. And in 2016, the Railroad Commission runoff pitting Wayne Christian against Gary Gates drew just 376,000 voters—a measly 2.6 percent of the state’s registered voters. (That’s just 1.3 percent of the total Texas population!)

This year is following a similar trend. Through Thursday only 7.25 percent of registered Texans had voted. But, hey, that just means that 93 percent of y’all still have a chance to vote and make your vote count.

There is no shortage of important races. In many congressional districts, there are closely contested primaries. If you live in Northeast Texas’s First Congressional District, you can decide among the four Republicans and four Democrats vying to represent the ultra-conservative district vacated by none other than Louie Gohmert, who, by the way, is one of three Republicans challenging the scandal-generating, forever-under-indictment Texas attorney general Ken Paxton. If you live in the Panhandle, you can decide who will likely replace outgoing moderate-ish Republican Kel Seliger in the Texas Senate. If you’re a Democrat living in the Austin-to–San Antonio Thirty-fifth Congressional District, you can pick among four candidates vying for this deep blue seat, including lefty Austin city councilman Greg Casar and state representative Eddie Rodriguez. If the Railroad Commission is your thing, you have an embarrassment of riches—or is it rich embarrassment—on the Republican side. As my colleague Russell Gold so aptly put it in a headline: “One Candidate Shows Her Breasts. Another Dies Tragically. A Third Is Accused of Graft.”

I could go on, but you get the point. Vote in March to make a difference in November. Early voting ends Friday; election day is Tuesday.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Redistricting