This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A tractor’s nice, but today what a farmer really needs is a personal computer, a mastery of finance, and the ability to outsmart the feds.

One year ago Max Thomas, a dark, husky young man with an animal husbandry degree from West Texas State University, was earning nearly $50,000 a year as an agricultural loan officer at a Lubbock bank. His job rankled him. The hours were long, the meetings were numbing, and most of all, Thomas didn’t like saying no to farmers and stockmen—and by 1985, that was almost all he was doing. The strain of it finally got the best of him. Depressed one evening because earlier that day he had told five farmers that their credit would not be continued, he went drinking. On his way home Thomas passed out at the wheel, and his car rolled into a bar ditch. He woke up in a hospital to discover that he had broken his spine and was temporarily paralyzed. The accident gave him time to think—about his origins, his work, and his future. A few months after he had recovered, in the fall of 1985, Thomas quit his job at the bank.

For seven years as a loan officer, he had watched farmers and cattlemen perish. He had learned just about all that could be learned from their mistakes. Today the 33-year-old Thomas is raising a thousand head of cattle and growing wheat and cotton on the four thousand acres he rents near his home in the Acuff community, just east of Lubbock.

Thomas knows that going into agriculture today seems about as foolhardy as following Bunker Hunt’s rules for investing in silver. But Thomas says that a profit can be eked out of the land, even in hard times. Though the cattle market is glutted and herds are being reduced, and though 10 to 20 per cent of the farmers on the South Plains have declared bankruptcy, Thomas plans to succeed. “I don’t think that a lot of the farm failures we’ve seen are the farmers’ fault,” Thomas says. “But if a man watches his expenses and thinks over what he wants to do, he can make a living at this business.”

So far, his plan is paying off. Most of the land Thomas rents was not sown in anything; native grasses and mesquite grew there. Thomas left much of the rough land alone. He seeded 1500 acres in winter wheat and wintered nearly a thousand head of yearling steers on his wheat and grasslands. When his wheat crop matured last spring he didn’t harvest it. Instead, he let the cattle continue grazing on it until the next planting.

One of the fundamental lessons Thomas learned from his years at the bank is that a farmer has to know how to make federal programs work for him. The trick, Thomas says, consists of understanding the details. For example, Thomas took advantage of a $20-per-acre federal subsidy for wheat plantings. But there isn’t a subsidy for harvest costs, and Thomas calculated that if he paid to cut his wheat and haul it to an elevator, he would lose money. Leaving his crop in the field saved him work, risk, and worry.

A similar strategy pegged to cost reduction also promises Thomas a startling profit from his 1986 cotton crop. Instead of planting six hundred acres in cotton, which is the maximum allowed on his farm under federal supervision, last spring Thomas planted on 52.8 per cent of his allowable acreage. A full planting—and maximum plantings are an old tradition on the South Plains—would have brought him about $68,000, a figure that includes the benefits from federal price-guarantee and loan programs. But when he subtracted from that his own expenses for seed, insect control, weeding, insurance, and harvest, the former banker discovered that planting only half as much cotton promised to bring in $64,000. “I’m sure that I could die and go to hell and come back, and there would still be cotton planted turnrow to turnrow on the South Plains,” Thomas says. “But I think we ought to be careful about that. Cotton isn’t near the crop that it used to be.”

Thomas’ decision to plant 52.8 per cent of his allowable cotton acreage reflects the logical precision of a relatively new farm tool, the personal computer. Thomas, who grew up on a Lubbock County farm, perfected his computer programming skills during his years as a banker, and today he shares a lot of his programs with his neighbors.

Not all his equipment is high-tech. Like any South Plains farmer, Max Thomas owns tractors, planters, discs, and drills, but he didn’t buy them new. The surpluses of his ruined neighbors—farm-sale and secondhand equipment—have provided him with machinery for at least half the showroom cost. Thomas borrows money to pay short-term operating expenses, as most farm survivors do. But he hasn’t borrowed to buy land. “I don’t reckon I’ll ever own an acre,” he says, “because today you can rent it so cheaply.”

This year’s profits, he estimates, will come to about $35,000, a figure that, with the tax benefits that accrue to family farmers, makes him nearly as well off as he was at the bank. His wife, Sharon, still works as a teacher’s aide, and at planting time Thomas spends sixteen-hour workdays in his field. “When you’ve got a family like I do, money can’t be everything,” he says, “but right now, I’m doing good on that front too.” —Dick J. Reavis

Oil’s at a new low, but so are mineral rights, royalties, and rigs. One wildcatter who left behind that $40-a-barrel lifestyle says now’s the time to drill.

“It is like J. Paul Getty says in one of his books I’m currently reading,” says Charlie Langston, unbuttoning his Armani sport coat and gazing for a beat at the ceiling of his Turtle Creek condominium. “Buy low, and sell high. And right now this business is the lowest it’ll ever be.”

Charlie Langston is one of the few remaining practitioners of a vanishing craft: drilling for oil. He knows perfectly well that in these dread latter days, oil is bringing about $15 a barrel, but the man is as cheerful as a chipmunk. Taking advantage of plummeting drilling costs, bargains in office space, and his own remarkably debt-free financial status, he has managed not only to stay afloat but to prosper. His overhead is so low that he says he can make a profit by selling his oil at $10 a barrel. That, of course, depends on finding oil in the first place.

“Back when everybody was drilling,” he says, “you had to wait to get an available drilling rig. Now you can almost name your own price. So common sense would tell you that now is the time to drill. The only thing that’ll happen to me when oil goes back up is I’ll be a hero.”

Langston is thirty years old and, as befits a young wildcatter, full of beans. He has a flawless blond beard that only enhances the look of innocent expectation in his eyes. He lives in Dallas, but he grew up in Thackerville, Oklahoma, just across the state line. The family ranch had oil wells on it, and young Charlie soon became accustomed to the sight of royalty checks. After he left North Texas State University in 1977, he opened a Western wear store in nearby Gainesville, a good vantage point for observing the workings of the oil business.

“Most of my big spenders were independent oilmen,” he recalls. “Obviously, that intrigued me. I asked a lot of questions of those guys, and pretty soon I was leasing land on the side. One lady who came into the store was a widow who owned all the minerals on her land and wanted to sell them. I leased her land for five thousand dollars; sold it a few days later for sixteen thousand dollars to an independent oilman who came in to buy ostrich-skin boots.”

Langston finally liquidated his store so he could lease land full time. Around 1982 he started buying into drilling prospects. In those oil-boom days every dentist and attorney in North Texas had some sort of interest in drilling a well. Now, of course, the dentists are back to filling teeth, and the lawyers are filing bankruptcy papers. But Langston is still drilling. He credits his ability to persist in the business to two things: his freedom from bank debt (“I’ve always had a phobia about borrowing money”) and his restrained lifestyle.

“There are a lot of good, legitimate guys in unfortunate situations now,” he says. “But there were a lot of guys before whose lifestyles were based on forty-dollar oil. Now it’s gotten back to being a good, simple business. There’s a lot of opportunity right now, and you don’t have to stumble all over the guys wearing gold-nugget jewelry.” Langston’s own tastes are temperate but far from ascetic, and in fact his guiding spirit in the oil business is Duke Rudman, an oilman of legendary dash given to wearing plumed hats.

Langston isn’t the only oilman to see opportunity where others see desolation. The low drilling costs are starting to attract more and more “bottom-feeders,” people who still have the resources to gamble for oil and gas reserves, the value of which—they fervently hope—can only rise.

Langston has a core of six or seven investors, including Rudman—“guys I can call on a moment’s notice”—who will generally throw in with him on a deal and save him the necessity of borrowing from banks. He has drilled five producing wells in the last year and made some shrewd moves in buying royalty and existing production from various souls caught in the cash crunch.

Right now Langston is drilling two wells, one in Louisiana and the other in Hardeman County on a lease he acquired in a complicated maneuver after the original owner went bankrupt. The second well will cost less than $200,000 to drill, but the potential reserves, figuring $12-a-barrel oil, are $9 million.

The catch, of course, as always, is that Langston and his geologists may be wrong. But that’s what wildcatters are for, to take risks, and it’s good to know that in this era of dashed hopes and cautious expectations, there are still a few such throwbacks around.

“My life’s dedicated to the oil business,” Langston declares. “I try to take a vacation, and it just doesn’t work. I went down to Puerto Vallarta a while back. They only had one phone at the place I rented, and you couldn’t get a line out. I couldn’t speak Spanish, so I couldn’t even sell any royalty down there. I took six girls with me, and I was still bored.

“No, this is the business for me. I had a geologist that I tried to buy a prospect from two years ago call me up the other day and try to sell me vitamins.”

Charlie Langston shakes his head sorrowfully. “No matter how bad my business gets, if I wanted to sell vitamins, I’d a been a pharmacist.” —Stephen Harrigan

Opening a shopping center used to be like minting money. Now developers can hardly give away space. But a builder has got to keep building.

Lillian’s, a family restaurant in Amarillo, has been open only since August, but on this fall afternoon the business is as brisk as the cool Panhandle wind outside. Mark Davis, Jr., is cutting into his steak sandwich and explaining why he decided to go ahead with plans for development of the Tascosa Village shopping center, in which Lillian’s is a tenant. Construction on the project began last January, when Texas’ economy was reeling from a fresh dose of panic and turbulence as oil prices plummeted into the teens. About the same time as Amarillo’s most famous resident, T. Boone Pickens, was hedging his crude oil reserves on the futures market, Davis was sizing up a 4.9-acre piece of land in South Amarillo and wondering whether he should take a gamble. With his other shopping centers 60 to 80 per cent vacant, forcing him to offer discount rates and other incentives, Davis, 58, had some doubts about committing to a new commercial real estate venture. “But a developer just can’t throw up his hands and quit,” Davis says. “I just thought we’d have to work a little harder.” In the end his need to keep building won out. The first phase of Tascosa Village was completed in April, and the second phase will be completed next month. Phase one, 48,000 square feet, is 93 per cent leased, thanks in part to Davis’ son Pat, who acts as leasing agent for his father’s retail development, and his other son, Paul, who manages those properties, including Carpet World, a store that Davis owns and that was Tascosa Village’s first tenant. “The reason we went ahead with the project, even though it was obvious that retail space was way overbuilt and that there was a big slow-up in business activity, was that we felt that this was a location that needed to be developed,” Davis says.

Behind Davis’ decision to develop Tascosa Village is his belief that Amarillo is still growing, no matter how slowly. Amarillo felt the slump a little earlier than much of the rest of the state did. By the end of 1984 developers had already started cutting back, reducing the number of commercial building permits in Amarillo from 284 in 1983 to just 125 two years later. But the city’s latest retail vacancy rates are still at 18 percent.

“It took guts,” says Don Powell, president of the First National Bank of Amarillo, of Davis’ decision to begin a project in such a soft market. Powell ought to know. His bank was hard hit by the downturn. “We’re not extending credit the way we did five years ago. It’s not enough for a developer to be technically sound. With the economy the way it is, you have to know how to analyze the market—and Mark does,” Powell says of the man he’s been doing business with for twenty years. “We know he has the staying power, the cash flow, liquid assets, but more important, he knows he could be broke tomorrow.”

The son of a laundry-truck driver, Davis has lived in Amarillo all his life. He started out in the retail business—selling carpet and home furnishings —and eventually became enamored of commercial real estate development. Security Development Company, which he operates with two other Amarillo businessmen, together with the companies of his two sons, owns or manages 13 office buildings, 7 shopping centers, and 1200 apartments.

Davis has no grand theories for prosperity. “We’re country people,” he says. “We’re not as sophisticated as your developers in Dallas and Austin.” But Davis’ dress says success. He is clad in a smart suede sport jacket with a crisp button-down shirt that shows off his Virgin Islands tan, and his accessories include a gold necklace, a copper bracelet, ostrich-skin cowboy boots, and a couple of diamond rings. Driving through Amarillo in his Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham d’elegance, making occasional calls on his car phone, Davis gives me a guided tour of other developers’ failed projects. Here is a shopping center that’s badly located: “This road doesn’t go anywhere. There’s no residential development here.” Another is well located but has poor access: “All the traffic comes this way, and you can get in only from that way.” One half-completed center has an out-of-town developer: “You can’t just hang a sign out there with a telephone number. When a retailer is looking for space, we hear about it first.” The next project shows a misjudgment of Amarillo’s growth pattern: “It’s too far west, at least three to five years ahead of schedule.” Another is wastefully extravagant and has a peculiar tenant mix: “Italianate marble sure is pretty, but it’s expensive! And look, he has put a dentist in there next to a jewelry store! That shows how desperate they are.”

Mark Davis is not blaming these retail vacancies on the bad economy. He sees the economic downturn as a catalyst that hastens the demise of inept businessmen. But sometimes even Davis’ self-confidence falters. “I keep telling myself, ‘It’s going to be all right, it’s going to be all right,’ but sometimes I wonder, ‘Well, is it?’ ” —Barbara Paulsen

Texas banks have been hit with hoof-and-mouth disease. But Cattlemen’s State Bank believes that thinning out the herd puts it ahead.

Why would anyone of sound mind and portfolio open a bank in Texas in late 1986? “We were just lucky,” says Jim Schwertner, Jr., 35, chairman of the board of the new Cattlemen’s State Bank.

A couple of years ago Schwertner, whose family has run a cattle business in largely rural Southeast Austin for three generations, decided he was sick of the interminable drives required for the simplest financial transactions. So he contacted a few friends, mostly business people in his area, with an idea. After three days of phone calls he had $1.8 million in cash and a board of directors for the first bank in his part of town.

Almost as easy as raising the money necessary to start the bank was getting state approval for its charter. Schwertner and his colleagues could have begun operating within six months of the first calls. But they decided it was worth taking the time to do things right, to put up the kind of building that would bespeak the permanence they were seeking.

Cattlemen’s State Bank (“The name is not meant to connote strictly agricultural loans,” says Schwertner. “We felt it meant independence, ruggedness, and a willingness to change with the times”) opened the doors to its sprawling 23,000-square-foot copper-roofed building in mid-October. But between the time of Schwertner’s idea and the first day of business, Texas banks have been hit with the equivalent of hoof-and-mouth disease.

After oil loans started going bad, banks were going to rescue themselves with real estate loans. But a funny thing happened on the way to the bank: real estate went bust too. And please, let’s not even mention agriculture. The dire banking situation prompted the quick passage of two major changes in Texas law during this year’s special legislative session. One allows out-of-state ownership of Texas banks, the idea being to bring in huge cash reserves from healthier institutions, and the other permits state banks to open branch offices, part of the continuing move toward deregulation.

Schwertner admits that between the time he raised the money in 1984—the capitalization is now $2.5 million—and the ground breaking for the bank in December 1985, he had some concerns about the direction the economy was taking. “I looked at myself in the mirror a lot and had a lot of talks with myself,” he says. But according to Elizabeth Phillips Horne, 32, the vice chairman of Cattlemen’s board, what looks like disaster is actually serendipity. “We’ve got the soundest bank in Texas,” she says. “We’ve got no bad debts.”

“As the economy began to slide, we started to feel it was a blessing in disguise,” Schwertner adds. “I would have hated to have started two years ago, because if we had, we would have made some bad loans too.”

A nonexistent loan portfolio is a mixed blessing, however. “Part of what they say is true. They have avoided the mistakes, or trap really, of banks that have gotten caught in declining land values,” says James Hackney, an Austin lawyer specializing in financial institutions. “But the competition for good customers is quite fierce, and the good loans really aren’t there. New banks get the people who have been turned down at other banks.”

The people at Cattlemen’s think they have a secret weapon that will enable them to attract those few good customers. “It sounds so simple, most folks don’t believe it,” says Schwertner. “Personal service. People want to go back to knowing their banker. Our bankers will be in the lobby where you can see them.”

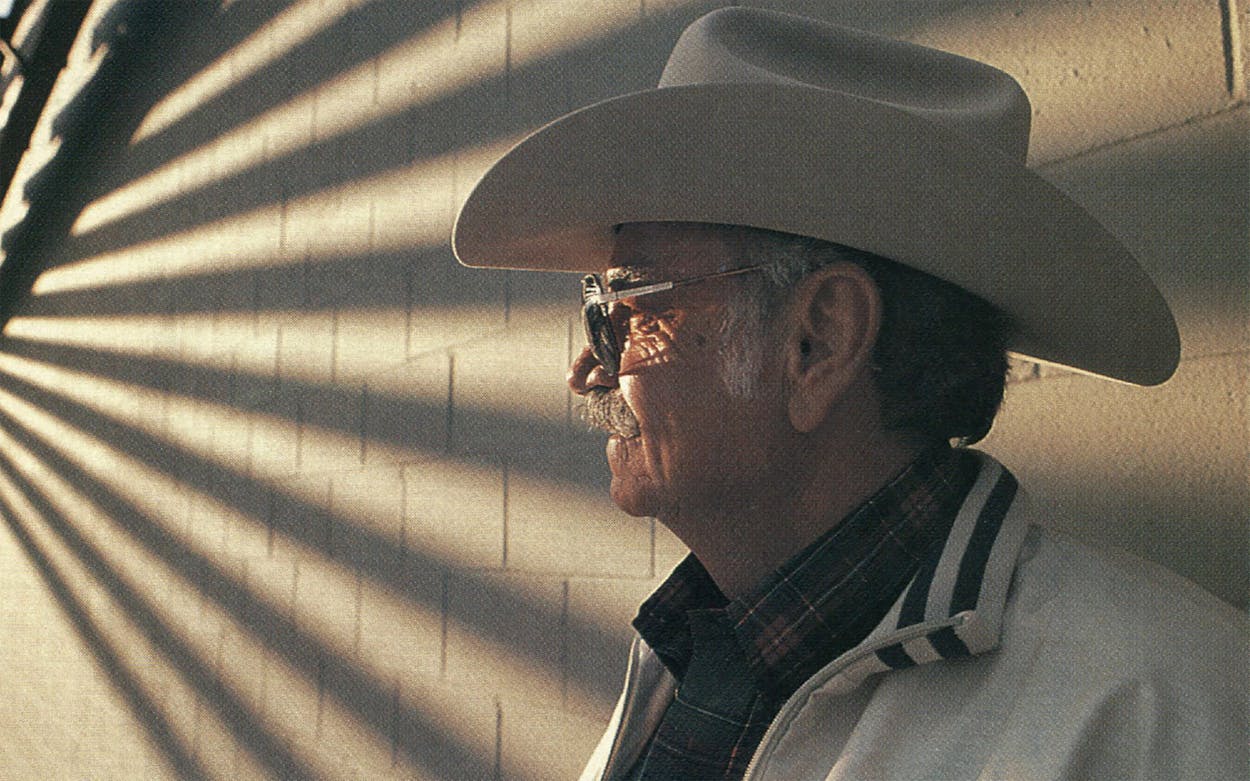

As far as Yankee-owned banks and branching are concerned, Cattlemen’s Bank says, let ’em come. Rancher and real estate investor Thomas Steiner, Jr., 60, who has put nearly half a million dollars into Cattlemen’s and is on the board of directors, says, “All that can only help us. A big complaint is that so many of the banks are owned by Dallas and Houston.”

Cattlemen’s plans to succeed by thinking local—cornering the market in an overlooked part of town. Bank president Gary Valdez, 33, who came to Cattlemen’s after eleven years at Texas Commerce Bank, says, “Most successful beginning banks are successful because the directors have financial stability and are willing to help the business development side.” Since most of Cattlemen’s directors live and work in Southeast Austin—each with a minimum cash investment of $50,000—the bank’s staff hasn’t had trouble persuading them to hustle for business.

Still, there is some nervous anticipation about the risks they’re taking. As Elizabeth Horne bustled about before opening day, supervising the final landscaping touches, she said, “This week three more banks closed in Harris County. I just tell everyone I have Alzheimer’s.” —Emily Yoffe

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads