It was July and Sage was hungover. She called saying she needed to jump into some cold water, so we headed over to Alia’s house, on the outskirts of Marfa, to use the stock tank in her yard. The dogs got in before us, poking their noses above the surface and pedaling their paws. The water was green and opaque, a fact Alia blamed on her husband, Jason. In an effort to reduce water waste, he had stopped letting the tank overflow, thereby also eliminating its single means of filtration. “Maybe you could get some fish,” Sage suggested to Alia.

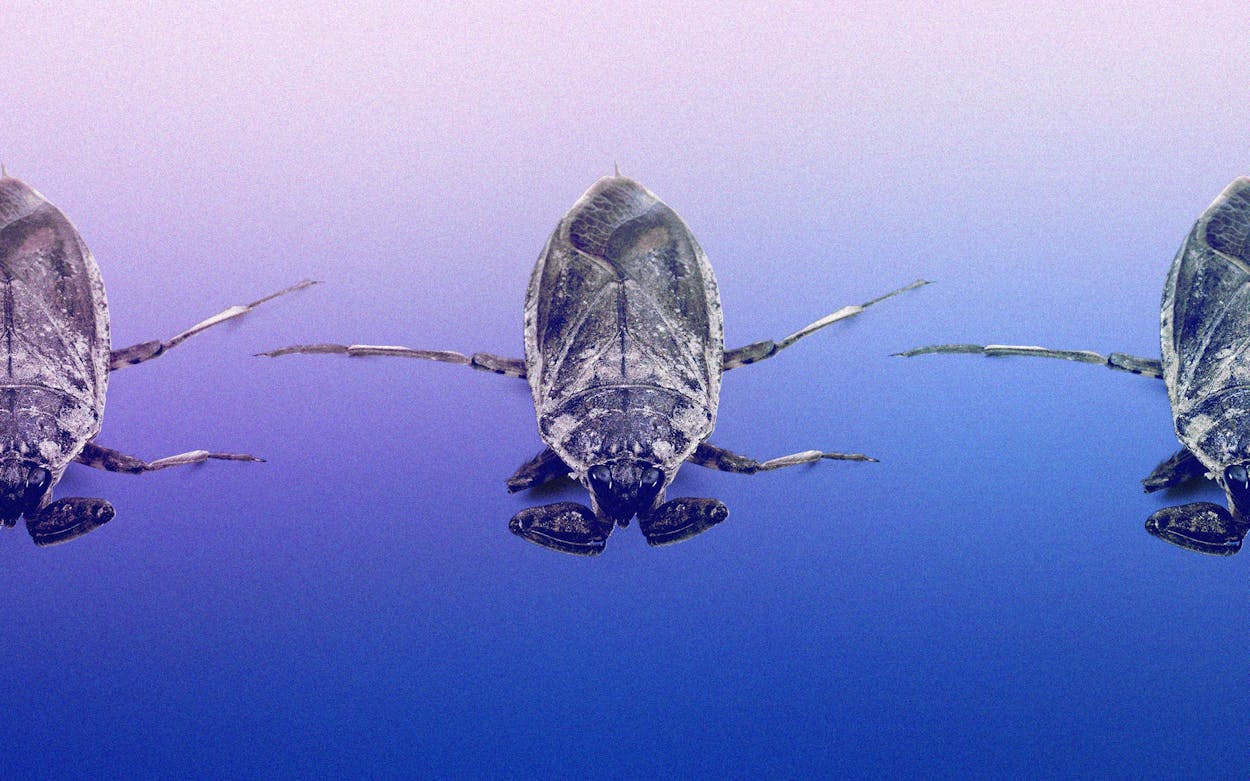

At least it was cold. I took two steps down and let my calves acclimate. Alia looked at me, then past me. “Big,” she said. “Big bug.” Behind me, a three-inch-long insect encased in dark armor floated just beneath the water’s surface. Its pincers were built thicker than its legs. I peered over my shoulder long enough to glimpse it, then clambered ashore with the resolve of the world’s first land animal. The creature disappeared again beneath the turbid depths.

Human ego permits us to assume that any man-made pool of water contains only what we want it to—that is to say, nothing but the self. With the sighting of “big bug,” our permission had been revoked, and we could only hazard a guess at what else awaited us at the tank’s bottom should we take the plunge. If there was one, were there others? In the distance, Jason ambled toward his workshop. “Boo!” Alia shouted in his direction, marking her disapproval.

But what was it? We stared at the water’s placid surface. Alia ventured to call the thing a water bug, but that didn’t seem right. My former home, a New York City basement apartment, had been replete with water bugs—like oversized roaches that, in a hair-raising display of natural selection, also possess the gift of flight—and yet I had never seen one quite that large. Sage seemed to have an answer: “It’s a Texas toe-biter,” she said, matter-of-factly. This didn’t bode well for our tank hangout, but Sage assured us: “They don’t bite unless you mess with them.”

Minutes passed before the insect made itself known again, lingering at the surface for a few moments before torpedoing back downward. On the deck, I scrolled through my phone for answers. The results were a terrifying panoply of macro-lens images and sources referring to the insect’s mouth as a beak. Other pages alleged that the bug delivers one of the most painful bites of any insect. Our brave and beautiful Sage, tired of waiting and still hungover, threw her lithe body into the tank. She surfaced again, bathed in a holy glow and unmarred by insect or bite.

In fact, both Alia and Sage were right. Members of the family Belostomatidae, as it’s known, go colloquially by many names—including toe-biter, giant water bug, and water roaches. There are around 170 species lurking in freshwater environments around the world. As for their propensity to bite—well, that’s another story.

Spencer Behmer, a professor of entomology at Texas A&M University, was in Costa Rica teaching a study-abroad program, and studying ants in his downtime, when I spoke to him on a video call in July. Given that he spends much of his time hanging out with insects, I’d naturally assumed Behmer had sustained his fair share of wounds; perhaps he’d even encountered the toe-biter’s eponymous attack—but no. “I don’t enjoy being stung,” he said. “I try to avoid it as much as possible.”

The toe-biter belongs to the order Hemiptera, also called “true bugs,” which includes bed bugs and assassin bugs. Their common characteristic is that they “feed by drinking their food,” Behmer said. “Think of their mouthparts as a straw. They will penetrate whatever it is that they’re eating.” Toe-biters eat other invertebrates, small fish and frogs, and—on rare occasions—even larger prey. “There are actually some records of these taking small birds out of the air,” wrote Richard Merritt, a professor emeritus at Michigan State University, in an email.

After piercing its prey, the toe-biter injects a cocktail of digestive enzymes that dissolves its victims’ insides into mush. Then they use that same straw to drink it. As Behmer tells me this, I can’t shake the sound of Daniel Day Lewis’s voice from There Will Be Blood resounding in my head: “I drink your milkshake!”

The mechanism by which toe-biters feed is somewhat similar to that of a mosquito (though the mosquito belongs to an entirely different order). Both use their mouthparts to penetrate and suck. But the similarities end there. Mosquitos, which Behmer lovingly describes as “flying syringes,” have a painless bite. Prior to feeding, they inject a chemical that acts as a numbing agent, so that you don’t feel their sting until after they’ve finished their dirty work, like a dentist administering novocaine before drilling your teeth. The predaceous toe-biter, however, bestows no such kindness on its prey. And it gets worse: as a National Parks Service page on toe-biters cheerfully notes in its Fun Facts section, “Another defense when disturbed is the giant water bug’s ability to squirt unpleasant smelling fluid from the anus for a few feet.”

After poring over an obscene number of bug images that will no doubt haunt me for the rest of my days, my best guess is that the toe-biter we found was of the genus Lethocerus, whose various species include one—Lethocerus medius—found throughout the southwest, from Arizona to Texas, as well as in Costa Rica and the Caribbean. The toe-biter is an aquatic insect whose natural habitats include ponds or riparian environments. So how, I wanted to know, did this aquatic insect find its way to the middle of the West Texas desert? Behmer told me that not unlike the water bugs that terrorized me in my former basement apartment, their more imposing cousin is also a capable flier. And a stock tank, particularly one that Jason had failed to clean, is a bountiful landing pad, rife with the sort of delicacies the species preys on: snails, beetles, maybe even frogs.

But that still didn’t explain how the bug found its way to the tank in the first place. Behmer suspected it might have sniffed out the water. “Insects have an acute sense of smell,” he said. Smell? I asked him. But how? “Antennae,” he said. “Think of antennae as a nose.” The notion that some people smell “sweeter” to mosquitos is true. In fact, it’s been shown that people with certain blood types are likelier targets of the bloodsuckers, who can spot the difference with those fibrous sensory appendages.

After our toe-biter had resurfaced numerous times, Alia finally trapped it and squashed the bug. It was only then that we discovered its trove of eggs, like a sleeve of pale green caviar, bursting from the rupture in its abdomen. Is there anything more tragic than telling an entomologist that you willingly killed his subject of study? As I recounted the incident, I struggled to look Behmer in the eyes, even via Zoom.

Behmer explained to me that one unusual feature of the toe-biter is that the female bequeaths the burden of parental care upon the male. In the case of certain species, the female will literally glue up to 150 eggs onto the back of the male—the appearance of which is truly the stuff of nightmares—before disappearing to pursue her own life, her own aquatic dreams. Other species within the genus Lethocerus deposit their eggs on objects or vegetation above the water’s surface, relying on the male to shade and moisten the eggs to protect them from drying out. This makes the toe-biter, just like the hardhead catfish, one of the relatively small number of animal species in which the dads do most of the childcare. I paused, marveling at this fact, and drawing a conclusion of my own: the toe-biter is a feminist.

Do I anthropomorphize? Very well, then. I anthropomorphize. The toe-biter is large; it contains multitudes.

One of the most striking aspects of our encounter with the bug was how, after surfacing briefly, it would then, quite suddenly, nosedive underwater. As someone well-versed in the potentially devastating consequences of spending time underwater, thanks to the recent events of the Titan submersible, I wondered how it was that an insect could submerge to such depths without harming itself. The pressure is not actually that intense, Behmer assured me. Rather, the greater feat is the toe-biter’s ability to breathe underwater. It accomplishes this with a tube at the tip of its abdomen that, like a tiny snorkel, the toe-biter sticks out of the water and uses to take in air, which it traps in an air bubble beneath its wings. Underwater, it uses this air bubble to breathe via openings on the sides of its abdomen. After a few minutes, this bubble depletes, at which time it’ll surface again for more air.

But we still hadn’t answered the most pertinent question of all: How bad was the toe-biter’s bite, really? If you’re like me, you might feel compelled to wander down the rabbit hole of YouTube videos featuring self-described wilderness experts who volunteer the soft pads of their feet to the unwitting insect. In one video, the toe-biter brings a grown man to his knees, drawing only the tiniest trickle of blood from his big toe.

There’s a whole legacy of dudes stinging themselves that precedes the inception of YouTube. An Arizona-based entomologist named Justin Schmidt, who died earlier this year, created the Schmidt sting pain index, dedicating his life to getting stung by various insects and then ranking their sting on a scale of one to four. Regrettably, he never got around to tangling with the toe-biter.

Behmer personally hadn’t ever been stung by the insect, and had only encountered it once in the wild, in Arizona. I guess there’s only one way to know—and frankly, I have no intention of finding out.

- More About:

- Critters

- Marfa

- West Texas