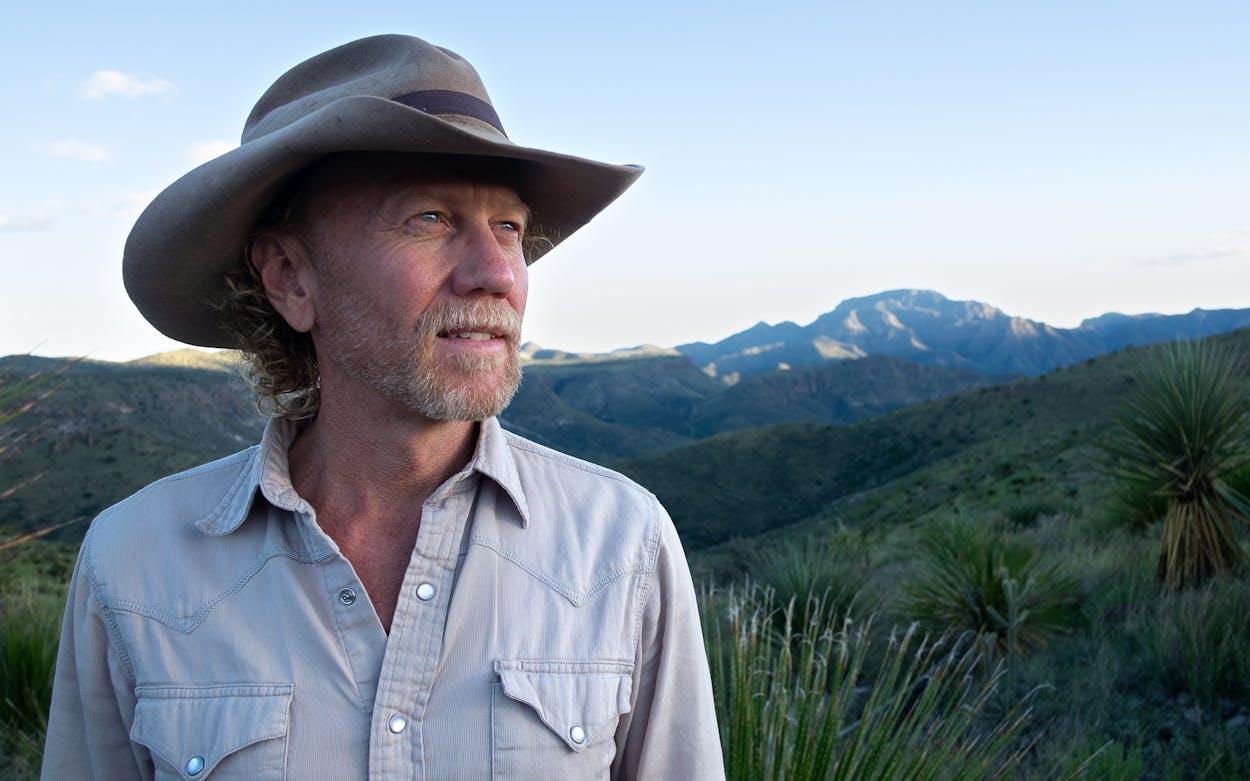

Whether perched against a mountain with the chill of the high desert wind blowing across his brows or steeped in the summer heat on the Texas-Mexico border to unravel stories from the past, David Keller is most comfortable in the outdoors. During 21 years at the Center for Big Bend Studies at Sul Ross State University, in the far West Texas town of Alpine, Keller has played a principal role in documenting the region’s nearly 12,000-year history. He’s excavated prehistoric sites where early inhabitants scraped out a living in the harsh desert, and he discovered evidence raising new questions about the massacre of residents of Mexican descent at the Texas border village of Porvenir in 1918.

For Keller, who grew up in Lubbock, landing a staff archaeologist job in the Big Bend was a dream come true—one that let him spend large chunks of time roaming thousands of acres of desert and mountains and then meticulously studying all the little pieces of the area’s history. But the dream turned to nightmare on December 14, when top university officials requested a meeting with him and greeted him with what he described as a cold, corporate-style termination. He was escorted by university police to the meeting. His office locks were changed. His computer and files were confiscated. Keller recounted the terse explanation from a university provost: “We’re not going to tell you why, and we appreciate your service, and you need to pick up your stuff and go.”

Keller, 52, says he was in the middle of three projects that may never be completed, including collaborative work on a massive archaeological survey of Big Bend National Park. He had planned on retiring in five years, at which time he would have received full health benefits from the state’s pension fund. “It was humiliating and sad and infuriating all at the same time,” he said. “That was my career, my livelihood, and much of my identity. To fire me in such a swift and cavalier manner felt very unfair considering my time there.”

The university’s president, Carlos Hernandez, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Louis Harveson, the provost at Sul Ross whom Keller said fired him, said he would not comment on Keller’s termination because it is a personnel issue. The director of the Center for Big Bend Studies, Bryon Schroeder, said that the termination was not his decision. “It was an issue that came to life with the university. It was a university decision,” he said, declining to comment further.

Keller isn’t sure about the exact reason for his firing, but he says the university provost told him it had to do with his research in Big Bend National Park. Park officials confirmed in a statement that the Center for Big Bend Studies contacted them in December regarding concerns about Keller’s work in the park, and that they suspended his permit to work there, but that Keller was fired before “any concerns could be cleared up.”

Keller said a park official told him the suspension was supposed to be temporary and reviewed for merit. The University and the National Park Service have not yet fulfilled open-records requests filed in January by Texas Monthly seeking documentation about the suspension.

About a hundred of Keller’s supporters attended a going-away celebration for him on January 27 at the Hotel Ritchey, in Alpine—all wanting to know why he was fired and angry over how the matter was handled. Keller had become an institution at the Center for Big Bend Studies, someone community leaders admired for his devotion to the region’s history. Many in attendance had worked with him and described him as the most ethical and hardworking archaeologist in far West Texas.

Keller is well known for his ability to get private property owners to let him conduct surveys on their lands. (Historically, many Big Bend ranchers haven’t been keen on letting anyone on their properties, much less an academic type who might try to restrict their use of part of the land if something historic is discovered.) He has prolifically published research and has written two books, including 2019’s In the Shadow of the Chinatis, a chronicle of the geology of Presidio County, its early inhabitants, and the settlers who carved out ranches in the mountainous area. The volume won the 2020 Al Lowman Memorial Prize, which honors best book on Texas county or local history, from the Texas State Historical Association.

Keller also cofounded the Big Bend Conservation Alliance, which fought the controversial construction of the Trans-Pecos gas pipeline running from Fort Stockton to Presidio and across the border into Mexico, and serves as president of the Friends of the Ruidosa Church, a nonprofit that’s restoring a historic church on the border west of Presidio. (I joined the board of the nonprofit in October, although I had never met or spoken to Keller before reporting on this article.) It makes sense that an archaeologist who sifts through the land might also want to know how to build with it. So Keller, with the help of anyone he could find who would share their knowledge, learned to work with adobe—mud and sand bricks used for many of the homes and buildings in the region—and led a project team on the preservation and reconstruction of the Dorgan and Alvino houses in the national park.

Keller received notoriety in recent years for his work at the Porvenir Massacre site, in Presidio County. In 2015, he led a team funded by Jerry Patterson, a former Texas land commissioner and state senator, to excavate the site where fifteen unarmed boys and men of Mexican descent were lined up and shot to death in 1918 by a group of Texas Rangers and ranchers. Keller followed up with a 2021 excavation, during which he unearthed bullets and cartridge casings that he said support a theory that U.S. Cavalry members may have participated in the shooting, countering the existing narrative that they merely led the Rangers to the town.

Patterson was shocked to hear of how Keller’s termination was carried out, particularly since he found the archaeologist’s work to be professional, meticulous, and solid. “Let’s assume there was a legitimate cause for firing him,” he said. “That still ain’t the way to do business for a guy that served that institution for quite some time.”

One ranch owner who forged a working relationship with Keller, Anne Calaway, has responded to his firing by asking the center to return all artifacts and survey data collected on her ranch. She has threatened legal action if it doesn’t comply. Calaway first worked with Keller in early 2019 to allow archaeological surveys of her Boot Ranch, near Alpine, and she bought the Hotel Ritchey with him in late 2021 to ensure that the historic structure would be restored. “When we first started this three years ago, [the center] convinced me that I might be a poster child for landowners,” she said. “Let’s do this and let us have access to your ranch, and let’s see if maybe as a result of this, we might not have better relationships with landowners out here.”

Several archaeologists close to the center’s work said that Keller’s relationship with Schroeder, who became the center’s director in 2020, had soured. Keller’s firing came after four other archaeologists left the center over the past five years. Eden Meadows, an archaeologist at the center from 2019 to 2021, said she witnessed the deterioration of staff morale and said Schroeder created a “toxic” work environment that spurred her to leave. She said Schroeder put her in an office in a basement that was later remediated for mold and that stored human remains from excavations. “As soon as I said, ‘Why am I with these bodies in a black hole,’ he wouldn’t talk to me. He would ignore me and then suddenly blow up on me and criticize me in front of other people.” Meadows said the work environment became increasingly hostile after she questioned why the center wasn’t addressing what should be done with the remains, which she eventually put in Schroeder’s office. “I quit before they could fire me.”

The three other archaeologists who left the center in recent years—Roger Boren, Sam Cason, and Richard Walter—declined to comment for this story. Ashley Baker, who worked at the center as an archaeologist from 2008 to 2012, kept close ties with her former coworkers there and said Schroeder had an “ego” that led him into conflicts with staff, and that he would mete out the “silent treatment” to those who disagreed with him. She described the situation of one former colleague who left the center. “No one would talk to him. No one would tell him why . . . for months. And he was devastated.”

Schroeder did not respond to questions about his relationships with his staff members. Sul Ross’s director of communications, Betse Esparza, did not respond to specific allegations either, writing that “it is the university’s policy not to comment on personnel matters.”

There is only one full-time archaeologist left on staff, Erika Blecha, who declined a request for an interview. Andy Cloud, the former director of the center who hired Schroeder, described him as a “capable and bright guy” but said he could not speak to Schroeder’s recent relationships at the center.

Ken Durham, an Alpine resident and a former member of the advisory council of the Center for Big Bend Studies, who resigned partially in protest over Keller’s firing, said he believes Schroeder’s actions were driven by more than personality conflicts. The center recently received a $1 million U.S. Department of Education grant, which will allow it to hire for three new positions to build up its now-depleted staff. “It’s pretty obvious to me that he’s going to be bringing in his buddies,” Durham said, “for new efforts to build a department run from his perspective. The way he is going about it just leaves a really bad taste in everybody’s mouth. It’s a total freakin’ mess.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Higher Education

- Alpine