Nobody could tell a story like Roxy Gordon. He would stay up all night on the porch of his house in East Dallas—this was in the eighties and nineties—surrounded by artists and musicians, spinning tales, singing songs, drinking vodka. Roxy, who wore his dark glasses even at night, had the charisma of a rock star, with long black hair spilling out of his cowboy hat, a coyote-tooth necklace, and a tattoo of an eagle on his left forearm. In his deep West Texas drawl, he would talk about growing up in a small town near San Angelo, going off to Montana to live on the Fort Belknap Indian reservation, or the time he met Willie Nelson. The books he’d written, the albums he’d made, the magazines he’d started. Roxy knew his Western history and told about the Indians in Texas, their struggles with Anglo settlers, and his own journey as a man of mixed blood. Some of his stories would change with the telling, but no one seemed to mind.

His home, which he shared with his wife and two young sons, was well known in Dallas as the Bone House because of all the skulls, femurs, and vertebrae from cattle, horses, and sheep hanging from the ceiling on the front porch. Almost every night there was some kind of gathering under the bones, with Roxy holding court. Sometimes the famed songwriter Townes Van Zandt would come over and the two would stay up all night drinking. They shared the same birth date and were similar characters: stubborn, whimsical, alcoholic, doomed. “Roxy Gordon is a brother of mine,” Van Zandt said once. “I don’t like the word ‘poet’; it is usually used too lightly. Roxy, however, is a real one.” Van Zandt died of hard living on January 1, 1997, at age 52. Roxy met the same fate three years later and two years older.

While many Texans know Townes’s dramatic story, few have heard of Roxy, an outsider who enjoyed bewildering everyone he met. From the start, as an imaginative boy in a small town, Roxy was determined to do his own thing—writing, drawing, painting, storytelling. He grew up to be, in the words of his friend Sally Wittliff, “one of the world’s first hippies,” a subversive and literary troublemaker. “Roxy Gordon is one of the great outlaw artist misfits,” artist and songwriter Terry Allen once said. Roxy made albums, though he wasn’t really a musician, and wrote songs, though he wasn’t really a songwriter.

He worked as a Native American activist, though he wasn’t really a Native American. He said he was—and he might have believed he was—but Texas Monthly was unable to find any evidence that he had Native heritage. Today Roxy, who was intent on creating his own artistic identity, no matter the cost to himself or those around him, would be called a “pretendian” or a liar. He would say he was just telling stories. “I don’t know the difference,” he once wrote. “Truth, lie, all the same thing. I’ll use either one that’ll work. Either one I can get away with.”

Roxy Lee Gordon was born March 7, 1945, in tiny Ballinger (35 miles northeast of San Angelo), and grew up in tinier Talpa, a few miles away. He was an only child. His mother ran the post office and played piano in the Methodist church, and his father was a World War II vet who spent much of his time drawing and painting. Roxy was an artistic kid, always drawing and writing, something of an oddball in a town where most of the other boys played sports. He loved history, often immersing himself in stories about the Alamo and the Civil War. He had plenty of Texas history in his lineage, including several Texas Rangers, one of whom was his great-grandfather. His grandparents owned a house about six miles east, in the area near Bead Mountain, and he spent a lot of time there. He called it the Hill and wrote about it in mythic terms. “The Hill was rugged and close, always in my sight, drawing me the way hills and mountains have always drawn human beings. I was both fascinated and afraid.”

Inspired by the Beat poets and writers, he played guitar and read Jack Kerouac. Roxy was determined to be a writer, and at Talpa-Centennial High School, he and his friend Mike Rush published a zine with their stories. Roxy was, he would later write, “always thinking and talking about writing, trying to discern what a writer might be, how a writer might approach life and experience.” He published another zine as an English major at the University of Texas, where he’d enrolled because he’d heard “that Austin was full of communists, and it sounded pretty good to me.” For the four-page newsletter, Ramblings, Roxy wrote fiction and poems; his new wife, Judy Nell Hoffman, created the art; and friends of theirs wrote nonfiction and poetry. Roxy was an early agitator against the Vietnam War, excoriating world leaders in a 1965 essay: “Murderers! I wish you eternal nightmare.” He also wrote for the Texas Observer, penning a sweet, evocative short story about a meeting in downtown Dallas between two men from West Texas. When Roxy wasn’t playing the guitar with his folk singer friends, he was hanging out with writers, and he soon became editor of the student literary magazine Riata, working with young bucks such as Larry McMurtry and Dave Hickey. Roxy and his friends sat around the Chuck Wagon, a cafe in the UT student union, and told stories about what they would do when they got rich and famous.

Anxious about the draft, he and Judy joined the Volunteers in Service to America program in 1968 and were sent to tiny Lodge Pole, Montana, where the Assiniboine and Gros Ventre tribes lived on the Fort Belknap reservation. The couple resided in a one-room log cabin and published the tribes’ weekly newsletter, Fort Belknap Notes. They also became friends with an older Assiniboine couple named John and Minerva Allen; he served on the tribal council, and she was a poet. The two would become crucial to Roxy’s Native American journey.

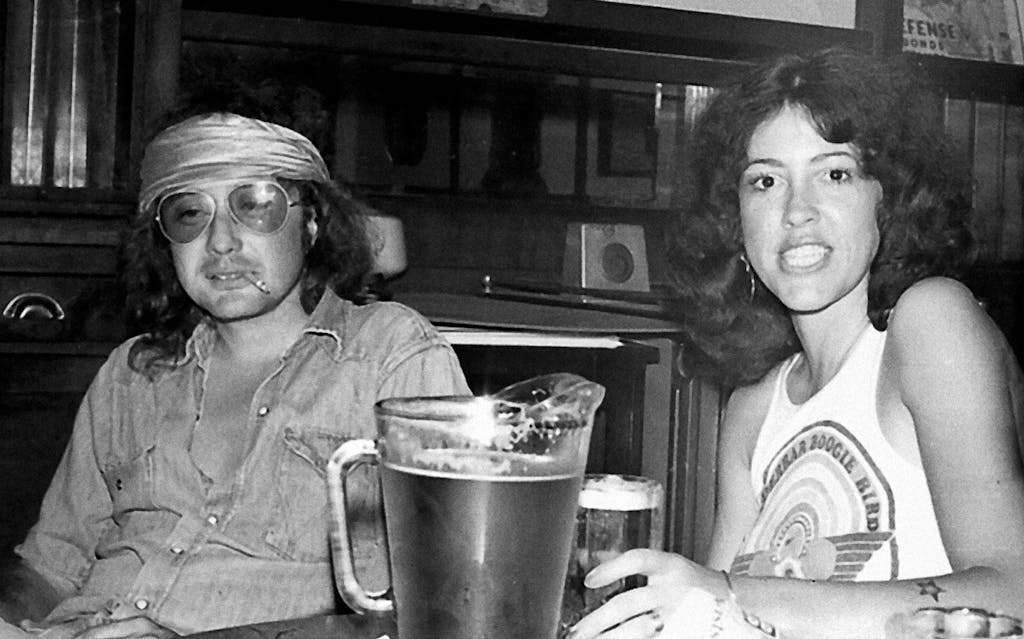

After a year on the reservation, the Gordons moved to San Diego, where Roxy—full of the hubris of youth—worked on a book about his life so far. In 1969 he attended a writer’s conference in San Diego and befriended hippie poet Richard Brautigan, as well as rock star poet Jim Morrison. Roxy and Judy met more poets and musicians when they moved north to Oakland, California, and hung out in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco.

After their son John Calvin (known as J.C.) was born, in 1970, the Gordons moved to Moriarty, New Mexico, near Albuquerque. In 1971, Bill Wittliff (later of Lonesome Dove fame) published the autobiography Roxy had been working on, titled Some Things I Did. It got good reviews; Texas Observer critic Steve Barthelme wrote of “the mean beauty of Roxy Gordon’s mind” and said that his gift is “to be self-conscious without being so terribly serious.”

During this time, Roxy wrote poems and criticism for the Observer in which he wasn’t afraid to go after his peers—including by taking potshots at Bud Shrake’s Strange Peaches (“a combination rich-Texan joke/liberal horror story”) and Larry McMurtry’s All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers (“another of McMurtry’s elegies for the west. He’s been killing off the west for years now.”). Roxy seemed to be going somewhere, writing essays for the Village Voice and Rolling Stone. In August 1973, Rolling Stone published a list of one hundred poets to watch, and his photo was under Nikki Giovanni’s and to the right of Louise Glück’s.

Roxy loved the progressive country music coming out of Texas, so in 1974 he started a magazine dedicated to the scene and called it Picking Up the Tempo, after the Willie song. Roxy did a lot of the writing, and he published up-and-coming journalists such as Joe Nick Patoski, Ed Ward, and Richard Meltzer. Like the artists he profiled—Willie, Van Zandt, Billy Joe Shaver—his own writing could be rebellious and inventive. In 1978 he penned a nine-thousand-word review of Butch Hancock’s debut record, West Texas Waltzes and Dust-Blown Tractor Tunes, for a British magazine called Omaha Rainbow. It’s a remarkable piece of criticism about an album that would later be considered a classic, with Roxy laying out—in four separate sections—the physical and cultural landscape of West Texas before going into the songs, all of it seen through the lens of his own West Texas upbringing. “Maybe,” he wrote, pondering reincarnation, “I’ve always lived on these prairies and maybe I will, for centuries to come.”

Ever since his time in Montana, Roxy had been fascinated with Native Americans, the ultimate outsiders. In 1979, he and Judy, now living in Dallas, named their second son, Quanah Parker Gordon, after the child of Cynthia Parker, an Anglo woman who was abducted as a child in 1836 by a Comanche band in East Texas. Roxy was immersed in Indian history, reading every book he could find and writing his own dark and bloody stories and poems about the battles between Indians and Anglos. Several times he traveled back to Lodge Pole to spend time with the Allens, who became his mentors. Roxy often reached out to them, said J.C. “He always leaned on John and Minerva when he himself was probably trying to find direction in his life.” In a Texas Observer book review, he had once written about “white Indians,” Anglos whose lives were changed after meeting Native Americans. In a few instances, he wrote, these Anglos “actually become Indians.” Roxy—child of West Texas, scion of a Texas Ranger—was determined to understand the Native American way of life.

So he “became” an Indian. Roxy’s poems and short stories began appearing in anthlogies of short fiction by Native Americans, such as Earth Power Coming. He cowrote a couple of plays with Choctaw author LeAnne Howe; their comedy Indian Radio Days would be performed dozens of times all over the country. He began reading his poems in bookstores and clubs in Dallas and Fort Worth. “He started getting a reputation,” said J.C. “If you wanted a counterculture opinion or if you wanted the Indian side of something, people just called. The phone was constantly ringing.”

Roxy and Judy were part of Dallas’s vibrant underground literary scene, self-publishing their own chapbooks of art and poetry as well as those of other artists. In 1984, a small Austin press put out a book of his Indian-themed poems, stories, and drawings called Breeds. The book featured a blurb from famed songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen. The couple had started their own publishing company called Wowapi Press and, in 1985, published Roxy’s book Unfinished Business. That same year Roxy worked with artist and songwriter Terry Allen to record a voice-over for his installation China Night, which explored how Native Americans who went to war in Vietnam encountered ancient relatives of theirs from thousands of years before.

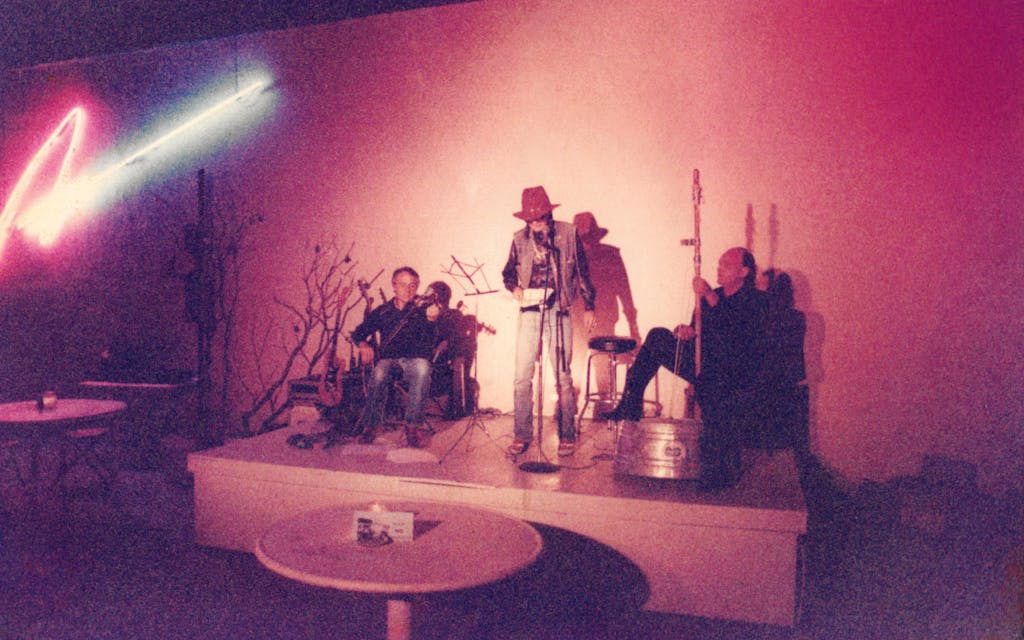

Roxy had always loved music, and in the mid-eighties he started performing his poetry with various musicians behind him at local art galleries and punk clubs, the perfect venues for his confrontational pieces about Indians. Friends such as Bill Johnston on fiddle and Frank X. Tolbert 2 on washtub bass would join him, and Judy or young Quanah would sometimes play a hand drum.

After the shows, the party would continue at the Bone House, in Lower Greenville, where artists and musicians hung out on the porch and listened to Roxy. His friend Mike Rush remembered how Roxy’s charisma drew people in. “He would turn an ordinary experience into an exploration. He had this ability to create these little zones that other people wanted to be part of.”

And they would stick around, sometimes for days, said J.C., who spent a lot of time in his childhood bedroom, away from the drinking and drugs. “There were people coming and going night and day, seven days a week. My dad was always playing real hard at cowboys and Indians. He passionately lived that lifestyle. It was the essence of his storytelling as an artist. That never shut off; that was 24-7.” Van Zandt, who would play Poor David’s Pub, just down the street, would crash on the Gordons’ couch for days at a time. Roxy was a huge fan of Van Zandt’s—he had once written about the “perfect darkness of his music”—and the two would stay up all night, telling stories and drinking vodka. Hard drinking ran in Roxy’s family, he wrote, and though friends such as Howe tried to get him to temper his excesses (sometimes including a quart of vodka in a day), he wouldn’t listen. Howe remembered, “He was like, ‘This is my life. This is the way I want to live.’ ” The drinking eventually drove her and other friends away.

Roxy started releasing albums of his poetry with music: Unfinished Business, in 1988, and Crazy Horse Never Died, a year later. Crazy Horse was a dark, intense affair, the music sometimes antagonistic (screechy keyboards) and other times sublime (fingerpicked acoustic guitar). His sympathies were plain to hear, from the title poem (“The white man came to Crazy Horse’s home and wanted buried resources there to run their white men’s world, but Crazy Horse said no.”) to “The Texas Indian,” a rewriting of the old folk song “The Texas Rangers,” giving the Indians’ point of view about a battle on the Rio Grande. The highlight of the album is “I Used to Know an Assiniboine Girl,” a bleak, heartrending story of a battered Indian woman who fought back against her abusive white husband and was sentenced to prison.

By this point he was saying openly what he had mostly only hinted at before: that he was Native American. He appeared on a public access TV show in Tyler and avowed that he was Choctaw on both sides of his family, though on his mother’s side he was also a fifth-generation Texan. “So I’m a genuine breed—lots of white and lots of Indian.”

Culturally, psychologically, and politically, yes. But biologically? Roxy had never talked about being Choctaw when he was growing up, nor did he write about it in his autobiography, and J.C. has never found any documentation of it. “I cannot find any evidence that my father was Choctaw or had Choctaw lineage in the family beyond what he expressed through his writings, art, and music,” he said. According to the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma membership department, Roxy was not an enrolled member of the tribe. Today, everybody from Bandcamp to the Texas State Historical Society to the Austin radio station KUTX calls Roxy Choctaw, but if he were alive, he would also be called a pretendian, like politician Elizabeth Warren, pop singer Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Canadian novelist Joseph Boyden.

To Roxy’s credit, he didn’t use his alleged heritage to gain fame or wealth. To his friends, the whole thing was a natural progression of his artistic personality. “He saw in the tribes people who were leaning into the past and living the past in their lives,” said Rush. “Seeing himself as a Native American gave him a unifying point of view to his written, visual, and spoken art.” Terry Allen agrees. “He was totally caught up in what was happening to Indigenous peoples in the West. That’s where his heart was and that’s where his visions came from.”

But art is different from life, said J. Todd Hawkins, a Fort Worth poet and citizen of the Choctaw Nation: “There has to be a genetic connection if you’re going to claim to be a Native.” Hawkins said he welcomes cultural allies who can write from an outside perspective without saying they are Indians. “I write a lot of blues poetry. I love blues music. But if I were to assume the persona of being Black, that would be problematic. That’s the thing about writing—you can pick up any persona you want to write a poem from. But once you step outside that persona and you’re the poet again, that’s where that line needs to be drawn. This appropriation is a part of what has been systematically done to erase a people.”

Anglos who take on Native identities are part of a long tradition of “playing Indian,” says Kim Tallbear, a citizen of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate nation and professor of Native studies at the University of Alberta, whether they are dressing up in football stadiums or around Boy Scout campfires. “This is part of a long-standing problem of appropriating our stuff,” she said, “our material resources and our voices.” She acknowledges that many who do it are well-intentioned, like Roxy: “Sometimes people find a more profound meaning in Native cultures, and there’s also a desire to belong to this land, not feel morally complicit in colonialism, in ongoing colonialism and the theft of Indigenous land. We have lots of people who do good things with our communities without lying about who they are.”

Roxy, the eternal outsider who had finally found his place in the world, did both. He falsely appropriated an identity for his own benefit—and he genuinely cared for and was embraced by his Native friends. He organized and played at benefit concerts and readings to help the American Indian Movement and to advocate for the release of Leonard Peltier, a Native American convicted in 1977 of murdering two FBI agents in South Dakota. Calling himself a “militant Indian poet,” Roxy helped put on a special day at the Kerrville Folk Festival that featured Native American acts. His good works and good intentions didn’t go unnoticed, at least by John and Minerva Allen. In 1991 they invited him to Montana and adopted him into their family. At the end of a four-day Sun Dance ceremony, Roxy was given a new name, and, at least for him, his transformation was complete. From then on, he was Roxy Gordon, First Coyote Boy.

Even as Roxy lived his artist’s life—self-releasing three more albums and several homemade books of poetry, as well as performing and speaking at workshops all over the state—he would travel back to Coleman County to visit his parents and the Hill. Once again, he would wander the terrain, feeling the presence of the past. “We spend as much time as we can there,” he wrote, “amongst ghosts and other mysteries and memories and a south wind that blows forever.”

In 1992, he started writing a column for the Coleman Chronicle & Democrat-Voice, and over the next eight years he would publish more than 125 stories. For thirty years he had been writing—as a callow journalist, a rock star poet, a strident activist—and now he seemed to find his voice as a seasoned veteran of Texas letters, writing in a wry, minimalist style about his wild life, the world around him, and his plans for the future: “All I want to do is write songs, prose, and plant a garden, maybe paint strange things on the side of the house.” You can hear Roxy’s love of history and his curiosity about people and why they do things as he tells stories his grandmother had told him—and relates adventures with Brautigan, Hickey, and Van Zandt, who (a week before he died) called Roxy and said he’d had a dream about moving nearby and starting a donkey ranch.

After his father died, in 1997, Roxy moved back to Coleman County for good, to help take care of his mother and aging grandmother. But Roxy himself was in terrible shape. He had always hated going to the doctor, and his final year was a difficult one, some of it spent in a wheelchair. He died February 7, 2000, of cirrhosis of the liver. “He drank himself to death,” Howe said.

Roxy was only 54, and it’s hard not to feel sadness at what could have been. “Bill in particular thought he had a lot of unused talent,” said Sally Wittliff, referring to her husband, who died in 2019. Mike Rush hated seeing Roxy’s self-destruction and thinks his charisma ultimately hurt him. “I wished he could have been able to stay focused on storytelling rather than being the wizard of this little cultural niche that he created.” Roxy was stubbornly Roxy, and Brendan Greaves of Paradise of Bachelors records, which rereleased Crazy Horse last year, thinks that has a lot to do with why so few today know of him and his work. “Part of his obscurity was willful,” Greaves said. “I think he self-sabotaged a lot.”

Roxy’s reputation probably suffered from his refusal to focus on one type of art—he was a writer, critic, poet, and visual artist. He was a bit of a trickster, said Rush, a shape-shifter. “He was an artist,” said Terry Allen. “I think Roxy lived pretty true to his desires, and you can’t say that about everybody.”

Greaves says he will be releasing some of Roxy’s other obscure albums, and J.C. is also trying to get more of his dad’s work out into the world. Growing up, J.C. had a sometimes fraught relationship with his distant father, and when he finally left home, he was resentful. “I wanted to leave and not look back,” he said. But a few years ago, after raising a son of his own, J.C. made a conscious choice to let go of his anger and get to know the man who had always been a mystery to him. He began looking through boxes of old stories, poems, and drawings, and he was so moved by what he saw that he set up a website to host them as well as photos of his mom (who died in 2022) and dad. He pored over the hundreds of stories from both the Coleman Chronicle & Democrat-Voice and Picking Up the Tempo. While he wants to find a publisher for them, he’s not in any hurry. “I miss my father,” he said, “but I have found a way I can cheat his death and meet him as a person, not as a dad.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- Writer

- Longreads

- San Angelo

- Dallas