Terry Allen likes to call himself an artist, full stop. The rest of us tend to complicate things. We like to call him a conceptual artist or a multimedia artist—or a singer-songwriter-playwright-sculptor-painter-pianist. We feel we have to, because he has played so many different roles in his life. Considered both a grandfather of alternative country music and a grand master of modern conceptual art, he’s written hundreds of songs and radio plays. His physical work sits in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and a dozen other museums, as well as Dallas Fort Worth International Airport and Bush Intercontinental.

Allen, who is eighty, grew up in Lubbock and lives in Santa Fe, and no living artist captures the darkness and light of the West as vividly as he does. You can hear the wide-open spaces of West Texas in his music, see them in his visual art, and feel them in the narratives his characters tell: indelible, darkly humorous tales of murder and mayhem, of romance and revelation, of leaving yourself and your love behind. Allen is serious about his work, but he’s a genial and self-deprecating guy who doesn’t take himself too seriously.

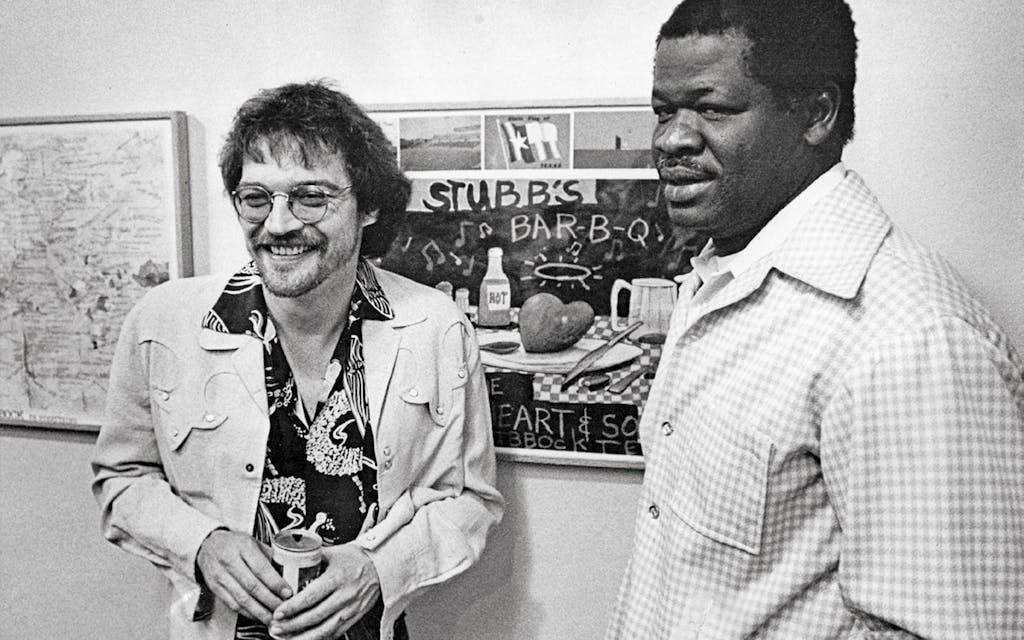

He’s staying busy at the start of his ninth decade—playing concerts, overseeing deluxe reissues of his works by the North Carolina record label Paradise of Bachelors, and talking about the nearly six-hundred-page authorized biography by Paradise honcho Brendan Greaves, Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen, which will be published by Hachette Books on March 19.

Texas Monthly: According to your new bio, you’ve been keeping a journal since you were in junior high. What got you started?

Terry Allen: I think it was Jack Kerouac’s fault. I started reading the Beats, and the idea of motion and writing and language started there. And I had a cousin, Billy Earl, who was in the merchant marines, and Billy Earl would dock in New York and buy a bunch of jazz records and come to Amarillo, where my aunt lived. That was my first exposure to jazz records and reefer and that kind of world.

TM: As a kid you wrote in your journal, “I want to be an artist. I want to be a writer. I want to be a musician.”

TA: I would do that periodically; the order always changed. And it never occurred to me that I would ever be any of them, much less be able to use all of those, you know, labels.

TM: There are so many great details about your parents in the book. Your dad was a pro baseball player turned wrestling and music promoter. Your mom was a barrelhouse piano player. So performing was in your genes. At those wrestling shows, you were six and would jump into the ring wearing a cowboy outfit.

TA: I would wrestle with some other kid and people threw money.

TM: Your dad promoted rock and roll, R&B, and country shows in Lubbock in the fifties. You saw Elvis, Hank Williams, Little Richard, T-Bone Walker. Who struck you the most?

TA: Bo Diddley. I was on a hayride with a girl, everybody freezing their ass off. But I heard this sound coming from a barn. And it was Bo Diddley’s first record. That rhythm was more inspirational than Jerry Lee Lewis or Little Richard, who I admired tremendously. Nobody could play piano like Little Richard.

TM: Though you pound the piano like Little Richard.

TA: Yeah, but with nowhere near the true aim that he had with those keys.

TM: Did you meet Elvis?

TA: Yeah, he came to our house. He came to get directions to the gig.

TM: You have this great memory in the book, talking about your dad’s dances: “I remember hearing that pounding music and seeing these elaborate porno drawings in the bathroom walls. . . . So I guess I always associated making music and making marks as the same kind of act. . . . I always thought that was my first real introduction to music and drawing together, the idea of art-making in different media at the same time.”

TA: Yeah, it was happening then. I hated going to school. And my dad was usually the one that woke me up, shook me and got me up to go to school. And I would try to hide under the covers, but I always would get an image of a pencil, and that pencil lead making a mark on a sheet. And it was such a comforting feeling to me that got me up and got me where I could get through it. But I always thought about that sensory thing of touch and making a mark—even then I had that kind of urge.

TM: When Brendan Greaves was researching your biography, he found things that you didn’t know. You thought your parents had met after your dad’s first wife died of throat cancer. But Greaves found that your dad had committed her to a mental hospital and then met your mom. Was that unsettling for you?

TA: Yeah. No one ever told me any of the details of anything. My parents just kept things to themselves. That knocked me off-center. I had such a firm lock in my head about what was going on with their lives, and I wrote about the stories they told me [in various pieces]. But whether the stories were true I have no idea. Probably some of them were, some of them weren’t. Some of them were gross exaggerations. Some were overt lies.

TM: You told me back in 1999 in an oral history on Lubbock music, “When I was growing up, I didn’t have a clue what I wanted to be. The only thing I knew that I liked to do was make pictures and play music. But the idea of it being something that you could do with your life—there was just no reinforcement for that.” You wanted to get out of Lubbock, but your new girlfriend, Jo Harvey, did not.

TA: Yeah, well, she didn’t have the necessity to get out, and I did. I had to get out because after my dad died, everything in my family was put in a state of collapse. I’ve always said that you didn’t have any memory until you got your first car because you had no reason to have a memory, you know? So when I got my first car, I wanted out of there.

TM: When you arrived in California at nineteen to go to art school, you met fellow Texan Boyd Elder, a painter from Valentine. How did that happen?

TA: I heard Boyd’s accent, and I was drawn to it. When people that come from those same forces that raised you—when you hear that sound, you feel like you know that person. I remember meeting Georgia O’Keeffe; she had that big painting of clouds, and she was showing it at a gallery in L.A. This was probably 1965. I was talking to the dealer, and she was in the office. She heard my accent, and she came out and asked me where I was from. I told her Lubbock, and she said, “I used to teach in Canyon, at West Texas State.” And she talked about how she missed that country and how beautiful it was.

TM: You wrote an early song called “Redbird” out there—and you played it on the TV show Shindig! There’s video on YouTube; you look like you’re still in high school, pounding that piano.

TA: That was weird because I was working construction for these guys up in the Hollywood Hills building this house, and I was waiting to get my check and they had a piano in the room, and while I was waiting, I went and sat down to start kind of messing around on the piano, and this guy just said, “Hey, you want to be on Shindig?” And I said, “Yeah.”

TM: What was it like when you’re playing and the teenage girls were shrieking?

TA: Not only were they shrieking, they were shrieking because I was playing the kazoo.

TM: Jo Harvey and you DJed a radio show called “Rawhide and Roses,” which was so ahead of its time, telling stories and playing songs.

TA: They were all themed shows each week—there would be illicit love, there’d be truck driving, animals, dogs. And Jo Harvey was amazing because it didn’t really matter what the theme was, she ended up talking about her family in Lubbock, but she did it so great. She was just like this kind of erotic innocent. And people loved that.

TM: You and Jo Harvey had two kids, in 1967 and ’68: Bukka and Bale Creek. I guess Bob and Bill were already taken.

TA: Bukka White [a famed Delta bluesman] is where “Bukka” came from, because I was listening to a lot of his music. And then Bale came along, and Jo Harvey and I, when we were in high school, we had always said, “Well, if we have a kid, we’re going to name him Beowulf,” and that’s where “Bale” came from. And then we both said, well, he needs something else, maybe we should put water in his name.

TM: In the late sixties you came back to Lubbock, you were bored to death, and you started putting together your debut album, Juarez.

TA: I actually started putting it together before that. I did a drawing called “The Juarez Device,” which was a hog-killing machine. When we got into Lubbock, the first song I wrote was “Cortez Sail.” And I did a drawing of it and then “Border Palace.” I wrote about three Juarez songs and several of the drawings I started in Lubbock. But that started the whole series.

TM: It took seven years, right? Your music and your drawing was feeding on itself.

TA: Yeah. And it was coming from places I still am very mystified by. I don’t know how that actually happened. I mean, I can go back and try to nitpick it, but it was just such an amazing series of events that happened—of things just coming to me and then making drawings and music, which were different than any drawings or music I’d ever done or thought about. So it was just a body of work that I feel like was really the first body of work I’d ever made.

TM: You couldn’t wait to get out of Lubbock when you left for California. But a lot of things had changed by the time you returned in the late seventies and recorded your second album, Lubbock (on Everything). You met Joe Ely, Jesse Taylor, and all of these Lubbock musicians.

TA: I played with a band for the first time on a recording. And it was amazing to me that when we listened back to that record, it was the first time I realized that these songs weren’t about hating the place. It was the absolute antithesis of that.

TM: You told me 25 years ago, “What happens is, you leave a place with a vengeance to get away from it to go find the world and find yourself and find what you want to do. And then running as far away from that stuff as you can, you realize that’s really where all your blood and history are. So you make a full circle and realize this endless resource to tap into in your work.”

TA: Yeah, I’m glad I said that.

TM: You, Butch Hancock, Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and Jo Carol Pierce are from Lubbock, and your melodies sound different from melodies that come from other places. Why is that?

TA: I’ve always thought it was the space—the space in the music is the same as the space you grow up in, and you can sense it. Jimmie Gilmore’s singing has always reminded me of wind going through the weather stripping in a house—that kind of moan that used to be in our house.

TM: Family is a big part of your art—you’ve written about your parents and collaborated with Jo Harvey, and your recent concert in Austin featured her, your sons, and your grandson Calder. Most artists and musicians keep their family over here and their art over here. What makes you want to do it all together?

TA: That’s happened naturally. I don’t think we encouraged the kids to make art. If anything, we needed accountants or doctors. But there were just so many artists and musicians at our house. I remember I once came home and there was a string that was going across the yard and a cross stuck on one side and a cross on the other side, and a mirror in the center of it. I said, “Bale, what is that?” He said, “It’s a vampire trap.” And I thought, “Okay, that’s pretty good.”

TM: When you wake up, do you think, “Well, maybe today I’ll write a song”?

TA: I still want to stick my head under the covers. No, I never did that. I’ll get an urge—a need to sit down and play and whatever. Sometimes I do it when I’m tired, if I’m doing something real tedious, I’ll go sit down at the piano and pound on it.

TM: And see what happens.

TA: Yeah. But there’s no particular way that it happens. I do make it a point to go to my studio every day to work. At least be there if something happens.

TM: Texas Tech University and its Special Collections Library recently acquired your papers. But at one point you were talking to the Smithsonian. Why did that fall apart?

TA: They called and asked me if I would give them my stuff. So I put together a box of catalogs, old tapes, work tapes, stuff like that, and sent it off to them. And they sent it back and said, “We only want the visual art. We don’t want the tapes and music.” And, more tactfully than this, I basically said, “F— you. That’s not gonna happen, because it’s all the same thing.” It’s not about labels. You have an idea to do something: You make a drawing, or you think of a sentence, or you sit down and play the piano. It all connects.

TM: What are you working on now?

TA: I’ve been commissioned to do a body of work on what Jesus Christ and Christianity might be like two thousand years from now. I’ve been working on it for about four years, writing songs, doing drawings, and getting ready to shoot some video. This foundation commissioned different artists to do biblical kinds of things, but I didn’t want to do Bible illustrations. I said I’d rather just project what the nature of the religion might be two thousand years from now—what kind of bureaucracy there might be.

TM: So what do you think Christianity in 4024 will look like?

TA: I signed a nondisclosure clause regarding any specifics. But considering the grand state of the way things are now, there probably won’t be a “then” anyway.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

A shorter version of this article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Terry Allen Doesn’t Care What the Smithsonian Wants.” Subscribe today.