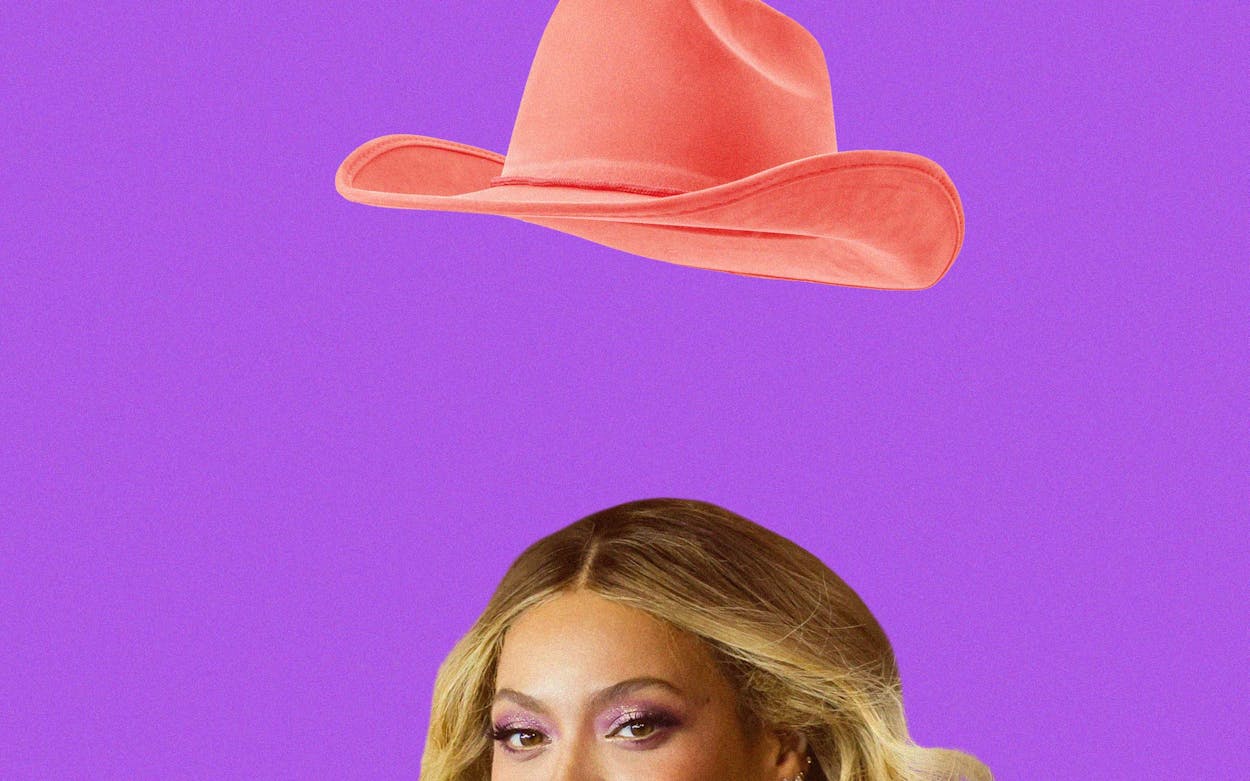

When Beyoncé announced more details on her forthcoming Cowboy Carter, she did so with a statement that clarified some speculation about whether she was aiming to cross over to country music: “This ain’t a Country album,” she wrote on Instagram. “This is a ‘Beyoncé’ album.”

In making that declaration, Beyoncé did more than just announce what fans might expect when they press play on Cowboy Carter for the first time on March 29. She also acknowledged a reality about the Nashville establishment that’s controlled much of country music since the Grand Ole Opry was built back in 1925. While her single “Texas Hold ’Em” has dominated the country charts since its release in early February (at the time of publication, it had held the top spot for six weeks), fully and successfully “crossing over” to country requires an artist to submit to the genre’s gatekeepers. The country music industry demands a degree of capitulation that Beyoncé has no interest in granting; doing so would be beneath an artist of her stature.

Country music has famously provided a second act for many artists—so long as they seek it on Nashville’s terms. That means working with Nashville labels, using preferred industry songwriters and producers, and nodding to the genre’s customs and culture. That transition has worked for artists as disparate in style as Jerry Lee Lewis; Hootie and the Blowfish front man Darius Rucker; Aaron Lewis, singer for the heavy metal band Staind; alt-rocker Elle King; and rapper Jelly Roll, who won the New Artist of the Year Award at last year’s Country Music Association Awards. That Jelly Roll was twelve years into his career by that point was irrelevant—his 2023 Whitsitt Chapel was the first album he made in collaboration with a slew of Nashville songwriters and established country stars. He may not have been a “new” musician but he was reborn, the same way that Rucker had been when he won the same award in 2009, thirteen years after winning Best New Artist at the Grammys as part of Hootie in 1996.

Beyoncé has thrown out the country crossover rulebook, and so she won’t be winning New Artist of the Year at the Country Music Association Awards this fall. Her career is soaring and has been for more than a decade; there are children who were conceived to “Partition” who are now watching TikTok dances to “Texas Hold ’Em” on their phones. When she flirted with Nashville in 2016, by performing Lemonade’s countrified “Daddy Lessons” at that year’s CMAs, she did it on her terms. The musicians who backed her were Nashville exiles (and fellow Texans) the Chicks, rather than a selection of session musicians or her own typical backing band. (That performance was received awkwardly—sometimes with downright hostility—by some country fans, some of whom shared their displeasure with the organization.)

When Jerry Lee Lewis went to Nashville in the sixties, the Beatles had driven his sound off the radio, and his scandalous marriage to his thirteen-year-old cousin had derailed his rock and roll career. When Rucker crossed over, Hootie and the Blowfish’s heyday was a distant memory. Beyoncé, by contrast, has made more of her first chance than just about anyone in the history of popular music. (Think about where Paul McCartney or Bob Dylan were 27 years into their careers!) She doesn’t need country to embrace her.

The country music establishment has long been ambivalent about whether to embrace an artist such as Beyoncé—a Black artist whose music is enjoyed largely (though hardly exclusively) by Black fans. To be sure, Nashville has made progress in recent years in opening up to artists of color. Black artists including Jimmie Allen, Kane Brown, Arlington native Mickey Guyton, and Rucker have achieved some measure of success there. “Black artists have always been there,” said country music historian Amanda Marie Martinez, author of the forthcoming book Gone Country: How Nashville Transformed a Music Genre Into a Lifestyle Brand and a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina. “There’s now just more attention on the fact that they exist.” But that attention doesn’t necessarily translate to support from the industry’s powers that be. Martinez notes that Guyton rarely gets played on country radio. (She hasn’t had a song land on Billboard’s country airplay chart since 2016). “Radio continues to be the most important factor in becoming successful in country music, and if it’s not a white guy, their chances go down drastically,” Martinez says. “If they’re not white and a woman, it goes way, way down.”

Some country stations initially rejected fan requests to play “Texas Hold ’Em,” and Bey’s team didn’t seem particularly interested in courting them, either; the song wasn’t even released to country radio at first. Even though the song has dominated the broader country chart, which includes streaming music, it has peaked at number 33 on the genre’s radio airplay ranking as of late March. It’s notable that, despite all of the obvious country elements in the song—it’s built around a banjo riff, a thumping drumbeat, and the most prominent card game metaphor in music since Kenny Rogers sang about knowing when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em—neither country radio nor Beyoncé has claimed the song as an example of the genre. “Country music has a very centralized industry that really dictates and controls how the music is defined,” Martinez said, “and other artists have to go through those gatekeepers.”

Beyoncé’s declaration that “this ain’t a country album, this is a ‘Beyoncé’ album” draws a line that the Nashville establishment has usually been the one to demarcate. It also reinforces what’s true of Beyoncé and few other artists: She’s a genre unto herself. That fact was demonstrated through the various diversions she indulged in on Lemonade, where she first dipped her toe into country instrumentation; tapped Jack White for a rock song; and worked with Ezra Koenig of Vampire Weekend on an indie-style pop tune. Those songs spanned styles in the service of creating a cohesive whole that was purely her own. Whatever precisely she has in store with Cowboy Carter, if the bosses of country music do want it, they’ll have to get it on her terms.

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music

- Beyoncé