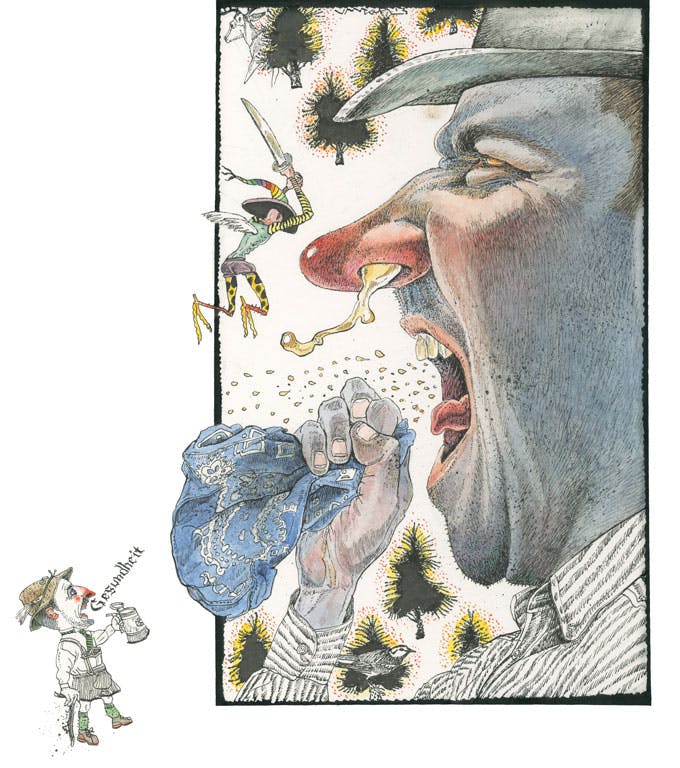

Q: I was born in Austin and have lived here almost my whole life. My wife was born and raised in New Orleans. After we got married, I convinced her to move to Austin. She loves it here, but she suffers so severely from cedar fever every year that she’s begun to talk about relocating to New Orleans. Can you recommend a cure for that pesky pollen?

Via email, Austin

Name Withheld, Austin

A: Nowhere is it written that a restaurateur need be shackled to the cuisine on which his ancestors were raised, nor that a particular grub must be prepared solely by a native of that food’s land of origin. The Texanist has enjoyed delicious all-American cheeseburgers grilled and plated by a surly man from Greece (sided with french fries not fried by Frenchmen), spaghetti bolognese prepared by an Englishman, spicy jambalaya ladled by a sweet Thai lady, delicious doughnuts made by a flour-covered Pakistani man, and peppy taco salad assembled by his own father, a man of Irish lineage. As well as so many complimentary saltine crackers with butter and salsa followed by so many Number Threes (with queso) at the very joint, he suspects, of which you speak—El Patio, on Guadalupe, north of UT, where the policy since 1954 has been “merely to serve the best”—that he dare not even venture a guess at the total number of cracker sleeves and Number Threes (with queso). Oh, so delicioso. Is it okay for a Tex-Mex joint to be owned and operated by a family of Lebanese descent? Yes, it is. Try the Number Three (with queso).

Q: I want to impress a newish gentleman caller of mine by baking him a pie, but I can’t decide between buttermilk, apple, and good ol’ pecan. Which one do you think will have more of an impact? The choice is yours, Texanist.

Carol Bustamante, El Paso

A: The answer to your pastry predicament depends on the type of impact you wish to elicit with this gift. Each variety, you see, can arouse a unique response. The silky buttermilk pie says to its eater, “Hello, I’m sweet and simple. I go down easy, but I’m a little unsophisticated.” The apple pie evokes an all-American wholesomeness reminiscent of one’s beloved and recently deceased granny. The Texanist assumes that neither of these impressions is what you’re after. Which brings us to the pecan pie. With its rich, dark, and gooey nuttiness, this sweet treat whispers gently to its recipient a mouthwatering love sonnet, a beautiful poem written with corn syrup and sugar upon flaky crust. If you think this suitor worthy, a fresh-baked pecan pie is the pie you’re after. Good luck.

Q: My family attended the Heart o’ Texas Fair and Rodeo, in Waco, this past October, and I signed my six-year-old son up for the mutton-busting competition, where the kids get to ride the sheep. He didn’t win, but he did pretty good, and he had an absolute blast. My sister was there too, but she didn’t let her son participate. He’s also six, and she thought it was dangerous. We’re still fighting about it, and we need you to settle it. Is mutton busting too dangerous for a six-year-old Texas boy?

Louise P., Hillsboro

A: The Texanist is no stranger to the adorably hilarious thrills and spills of the wild and woolly rodeo event known as mutton busting, in which little cowpokes, usually restricted to an age range of four to seven years old or thereabouts, are released into the arena on the back of a speeding sheep like a steely-eyed cowboy atop a rank and extra-puffy bronco. With two tiny fistfuls of fleece, the young rider hangs on for dear life as the sheep darts out of the chute. The action lasts for only a few seconds, but it’s always a big thrill for participant and audience alike. Typically, the mutton busters are outfitted with a helmet and sometimes a protective vest, and the event’s sponsors do often require the signing of a waiver, but the reality is that this is more about the litigiousness of the times in which we find ourselves than the actual dangerousness of sheep riding, which the Texanist finds to be comparable to the dangerousness of tricycle riding, somersaulting, or walking. The children come away a little dirty but otherwise completely unscathed—most of the time.

Q: I have lived in Texas all my life. In my early years I had the privilege of helping my parents raise and harvest sweet potatoes. Recently, when I was browsing through the produce department of our local grocery store, I was surprised to see a pile of perfectly good-looking sweet potatoes with a price sign calling them “yams.” What the heck is that?

Steve Goertz, Spring

A: Thank you, Mr. Goertz, for bringing to light an all-too-common mistake perpetuated by the United States government. Despite what the vegetable-shopping public reads in the produce section, yams are no more sweet potatoes than sweet potatoes are yams. The two are not even related—yams belong to the Dioscoreaceae family and sweet potatoes the Convolvulaceae clan. The USDA, though, stipulates that foods labeled “yams” must also include the words “sweet potatoes.” A more sensible rule would be for foods labeled “yams” to actually have to be yams, but that’s the government for you. Don’t ask the Texanist.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: If you send a love letter, addressed and stamped and slipped into a slightly larger envelope labeled “Valentine Remailing,” to Postmaster Leslie E. Williams at the “Love Station” in Valentine, Texas, 79854, she’ll hand-cancel it—with the annual Valentine stamp specially designed every year by students in Valentine ISD—and forward it along to your sweetie.