Nashville, Christmas Eve, 1975. Empty whiskey bottles and half-finished cups of wine glint in the warm glow of kerosene lanterns. A ring of songwriters are gathered around this forest of glass and lamplight, each with an instrument in his hand. Presiding over the circle is Guy Clark, the evening’s host. He tamps the end of his cigarette on the table as he chats with fellow troubadour Steve Young, who is dressed in all black from his boots to his wide-brimmed hat. Across the table from Clark, Steve Earle takes a pull of liquor straight from the bottle. In two weeks, he’ll turn twenty-one years old. Seated catty-corner to Earle is another youngster with pale, skinny limbs and a mop of curly hair à la Greg Brady. This is Rodney Crowell. He’s twenty-five and has been living in Music City for the past three years. His debut album is still another three years away. His marriage to Roseanne Cash (and their later split), his five Number One hits, and two Grammys all are even further down his timeline. On this night Crowell is just a kid with a guitar, a clear tenor, and a head full of songs. He closes his eyes and starts to sing, leading the group in a boozy but beautifully harmonized rendition of “Silent Night.”

So goes the final scene of the 1976 cult documentary Heartworn Highways, a film that chronicled the nascent, so-called “outlaw” music scene as it began to coalesce in Texas and Tennessee. Besides having a couple of his songs recorded by other artists, Crowell was virtually unknown at the time, a newcomer hanging around the peripheries of songwriting titans like Clark and Townes Van Zandt. But when Crowell performs his self-penned “Bluebird Wine” for the filmmaker’s camera, it’s easy to detect a self-assured swagger to the finger-picking, the lyrics and melody melding together as memorably as any other song in the film. It’s clear even then that this young gun from Houston had talent, not to mention the kind of wide-grin charm that helps sell records.

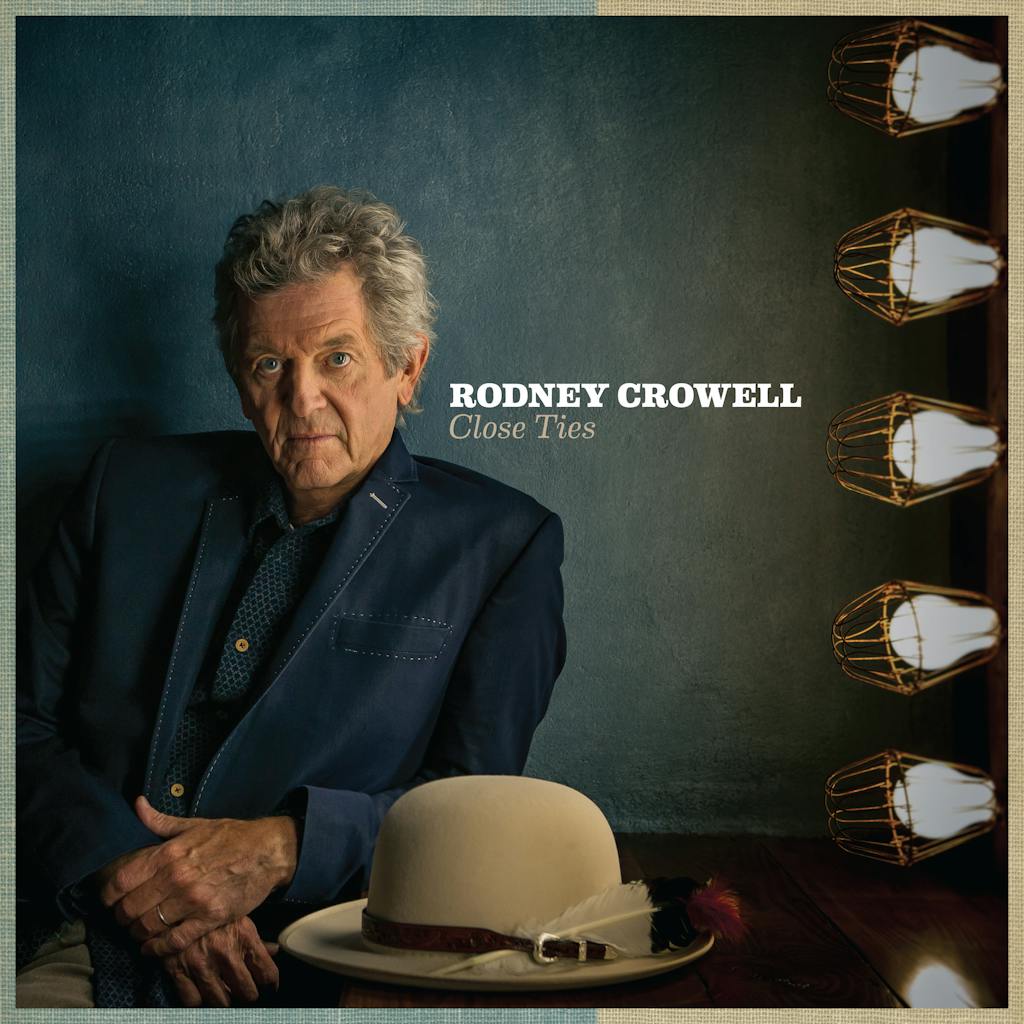

In the four decades that have followed that Christmas Eve jam session, Crowell has transitioned from the new kid at the table to one of the most masterful songwriters in country music. Like his early mentors Clark and Van Zandt, Crowell has carved his name deep into the mantle of country music history for his honest, intelligent songwriting. His latest album, Close Ties, released on March 31, mines his personal history—both his childhood roots in Houston and his rise in Nashville. By bringing his own biography to the forefront, Crowell provides a wider context to those brief glimpses of early promise in Heartworn Highways.

At 66, Crowell is now one of the elder statesmen of a generation that continues to thin with time. Just last year, he lost Guy Clark. Though his longtime friend and collaborator is no longer a short drive away, Crowell says he continues to feel a certain magic about Nashville—one he hasn’t been able to shake after all these years. But as Close Ties underscores, Crowell has never forgotten his Texas roots. The Houston kid is back in his home state for a string of dates starting with a two-night residency that began on June 28 at the Saxon Pub in Austin. From there he ventures to Houston for a Friday night gig at The Heights Theater, and ends his Texas run on Saturday at The Kessler Theater in Dallas. That’s four consecutive nights to witness this Texas truism: that the light burning at Clark’s dinner table in 1975 will continue to shine as long as Crowell is still pickin’.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Christian Wallace: One of your songs on this album, “East Houston Blues,” was inspired by your upbringing in Houston. Could you talk about what it was like growing up on the East Side?

Rodney Crowell: Well, the history of that—they had struck oil over on the border at Spindletop. Gushers were coming in, so they dredged a shipping channel fifteen miles inland. The whole east side of Houston along the ship channel became chemical plants, refineries, paper mills—the equivalent of Detroit. Actually my mother and father went to Detroit first from western Kentucky.

CW: What was their trade?

RC: No trade. My parents were sharecrop farm kids with no education—seventh, eighth grade. Looking for work. Detroit was too cold for them, so they eventually migrated to Houston where they heard there was work. My mother and father wound up in the Third Ward when they first came in. There was cheap housing for the refineries’ workforce there. Over on the west side was where those who came into money lived. But that ship channel bedroom community culture on the east side was very musical. There were a lot of icehouses—you know, two-garage-icehouses with sliding garage doors and a jukebox inside ’em, maybe a pool table. Music was always going.

CW: What kind of music would you hear?

RC: We were the first stop from New Orleans, so there was rhythm-and-blues. Frogman Henry and stuff coming out of New Orleans getting shipped west. But for me and my parents’ social circle, it was Hank Williams. Honky-tonk music. Ernest Tubb. Hank Snow. This was post-World War II, so one of the things about that culture was: Friday and Saturday night singing, and Sunday morning redemption. It was Protestant.

CW: What denomination?

RC: My mother was full-blown Pentecostal. But still, there was a culture there and music was a big part of it. The sexier, edgier stuff—even Ray Price when he started out with “Invitation to the Blues” and “I’ll Be There (If You Ever Want Me)”—I remember that music. There was a certain amount of rock’n’roll. To me Hank Williams is the first rock-and-roll star. Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, he’s like that: skinny, dangerous.

CW: All edges.

RC: Yeah. Angular, hunched over. Hank Williams brought that, and it was the end of the war so the world was coming back to its senses after having been knocked out. Music was sexy and fun. People were like, “We can live again. We don’t have any money, but this music is happening and we can drink beer and we can dance.” I was born in 1950, so that’s when I came in. Pretty soon, I’m two, three years old, and I started to feel that… freedom. Because music always meant freedom from the tediousness of working menial labor. My father played and sang, but he never graduated beyond playing local.

CW: He’d play in the icehouses?

RC: Yeah, he had a band—a really eclectic hillbilly band. He was good. He really was. A better singer than me. But he was a product of the Great Depression without education, so a steady job, even if it was a $1.80 an hour, was more important.

CW: Do you remember when you first wanted to be a writer?

RC: I had a high school band, but even before that I would drop the needle on records and lift the words. I kept a notebook full of words. This probably started in ’62. I really got into it when the British came over and the Beatles exploded or when Bob Dylan came on. I’d drop needles and fill my songbook. I did that for the longest time. Then I went to college at Stephen F. Austin in Nacogdoches. My roommate’s brother was a truck driver, but he was also a poet and a big Dylan fan. He’d come through with his truck and start playing us songs he’d written and reading poetry. I was like, “Wow, here’s this truck driver. He writes poems and takes speed and chain-smokes and talks about Bob Dylan.” I told my roommate, “C’mon, let’s do it. Let’s start writing songs.” The songs we wrote weren’t any good, but eventually it got us to Nashville. Luckily, that was August 1972, and by October I met Guy [Clark].

CW: You chronicle your early escapades in Music City on the song, “Nashville 1972.” Can you tell me about meeting Guy and what it was like back then?

RC: As I say in the song, I had a house on Acklen Avenue that I shared with [poet] Richard Dobson and [bassist] Skinny Dennis Sanchez. Somehow Guy and Susanna had heard this new guy was in town, so they came around. The first time I met Guy, he was passed out, face down on this little bed I had in the room I shared with Skinny Dennis. After that we just hit it off. Back then nobody had enough money to buy anything more exotic than some cheap dirt weed and cheap wine, but it was good fuel to stay up all night to play songs and trade songs and dream songs. It was all about songs. It was the perfect training ground, if you’d pay attention. I remember guys being around who’d try to hold court with limp songs and a lot of panache. But if you tried to jump to the head of the class too quickly, you’d get knocked down in a hurry. You get around Guy and that crew—Mickey Newbury and Townes [Van Zandt]—well, I was smart enough to be quiet and pay attention. I knew a lot of songs, but I hadn’t written any good ones. And I knew strange songs—quirky, weird murder ballads, like Appalachian “dead baby” songs that I learned from my father. So I could keep Guy interested, because I’d stay quiet and wait until he asked, “Well, what do you got?” And I’d play something I learned from my dad.

CW: Do you still feel some sort of magic in Nashville?

RC: Here’s the thing about Nashville, there is this big corporate machine that produces commercials for commercial radio. They’re not in the business of music; they’re in the business of selling commercial time. The creative community [in Austin] could take a really hard look at that. Because under that, there’s a fantastic, creative community in Nashville—Béla Fleck, John Jorgenson, Jedd Hughes, and I could go on and on about real, highly-developed artists and musicians. The possibility of collaboration is stunning and rich. And another thing, now and again the corporate side spits out checks to these brilliant artists. In a way, it’s almost like the government subsidizing artists. That allows them to say, “Yeah, I can deliver this commercial lick for you in my sleep, but in my heart I’m doing this.” That’s why you go to Nashville. If you can get there as a young artist and not get drawn into making money by creating disposable art, the water system’s full of artists who are working toward timelessness. That’s why I’ve stayed there.

CW: Do you think of yourself as a Nashville or Texas songwriter or do you make the distinction?

RC: I’ve always said that Guy Clark is a regional songwriter without being regional. He’s global. His craft is like, well, Larry McMurtry would be an example. I kind of see Guy Clark and Larry McMurtry in the same wave. McMurtry writes about West Texas, but he also wrote beautifully about Houston. With McMurtry’s writing, he would capture humanity with Terms of Endearment, that Houston and Post Oak scene, and in another novel he would capture the flatlands and the lights in West Texas. It’s regional sense of place but on a level with [John] Cheever and writers of that caliber.

CW: There’s universality in the specific.

RC: There you go. I aspire to that, whether I’m there or not I’m not entitled to claim. That’s up to the audience.

CW: Do you ever return to Houston or other parts of Texas outside of playing shows?

RC: My brother-in-law lives in the west side of Houston near Rice University in a sweet little spot of town. My in-laws live in Dallas. I’ve had occasion to go to Beaumont. My feeling about Texas—well, what you said summed it up: “The universality of the specific.” I guess I’m a Texas writer. I wrote a memoir [Chinaberry Sidewalks] about growing up in Houston. When I was writing that memoir, I came back. My mother used to drag me to church, so when I started writing, I said, “It’s forty blocks she drug me to church on Sunday.” I went back to Ave P in Houston, and I walked it. It was twenty-four blocks. That was fun—to go and walk those same sidewalks as a fifty-five year old man, fifty years later. I really like Texas in that way. It’s not nostalgia so much as it is place. There’s poetry inside place. “How does this change? And how does it not change?” And I really like the people.

CW: On the song, “I Don’t Care Anymore,” you say “It’s a hard knock situation when the accolades bestowed/On your every last creation cries out middle of the road.” Do you really feel that way about your work?

RC: No. I’m taking the piss out of myself from the get-go.

CW: You take the piss out of yourself a lot on this album. It’s very self deprecating.

RC: It’s not false. I really think about that. Think about Richard Pryor’s humor. It was very self-deprecating. Man, he would lacerate himself, but at the same time there was real swagger. “Yeah, I’m self-lacerating, but this self-laceration is contained inside a self-awareness as an artist.” I’ve created some middle of the road shit, but not everything. Since Houston Kid, I’ve got a pretty good track record. Before that I wrote some hit songs, but I didn’t come into my own until I was about fifty. Before that I had bursts of talent. Diamonds & Dirt was five number-ones on one record. When I hear it now, I realize that I was fusing my Buck Owens and Hank Williams upbringing with the harmonies and overtones of the Beatles. That came from an honest place. But while I was writing songs for Close Ties, I pulled out Diamonds & Dirt while I was looking for another record. I looked at the cover, and I said, “F—k. Look at this guy.” I told my wife, “I look like a poseur.” I gave myself a little shudder. I thought, “Man, I really was insecure at that time.” So I started working on [“I Don’t Care Anymore”]. I was taking the piss out of that insecure guy on the album cover, not really taking the piss out of the music.

CW: Since you talk so candidly about your past on this album, I have to ask, do you regret any of the decisions you’ve made in your career?

RC: No, I don’t. Well, I do regret a couple of things I’ve said about other artists. Some things I wish I could take back that served no purpose other than—I think I was propping myself up, you know. It’s easy to criticize somebody, rather than to train that criticism on yourself. I’ve made some stupid, insecure missteps. There are blank spaces in some of the albums I’ve made where I thought I was making this intellectual statement. Self-consciousness is the enemy of art. Some of those self-conscious roads you go down, you say, “I’m going to make this record; it’s going to be this.” Then a year and a half later, you hear it, and you go, “Oh shit. I wasn’t following my heart there.” I don’t really regret that, because that’s part of the learning process. There are moments in my recorded history pre-2000 that I go, “Ugh.” But who wouldn’t? I’m sure you can look at sentences you’ve written, and you think, “What was I thinking?”

CW: Like last week.

RC: That’s it exactly. You were overthinking. Insecurity gets in there and makes you make poor choices. But I don’t regret that.

CW: In Jason Cohen’s recent profile of Terry Allen, Allen mentioned that you and Guy were working on a song about a crow’s nest that Guy had seen in a windmill made out of bailing wire. Did y’all end up finishing it?

RC: It was the last thing that Guy and I collaborated on. The last few months Guy didn’t have any energy for anything, but he called me and said, “I’ve got this thing, and I need your help.” So, yeah, we finished it. I’ll record it. That’s probably the next thing I’ll do.