The honor of “most important band to ever come from Texas” will always be held by Buddy Holly & The Crickets, but allow me to make a case for At The Drive-In at second place. ZZ Top and Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble sold infinitely more records, but their work was largely reinterpreting Albert King, John Lee Hooker, BB King for a mass audience. Willie Nelson, Selena, Roy Orbison, George Strait, and Beyoncé all have greater achievements as solo artists, not in as the Highwaymen or Destiny’s Child. Janis Joplin and Sly Stone may be native Texans, but their respective backing bands were largely formed in San Francisco. Yes, you could make a case for Pantera, Asleep at the Wheel, or UGK, maybe, but anybody who lived on the border in the late nineties and had an interest in indie rock knows the truth: At The Drive-In mattered more than anybody else.

At The Drive-In’s story is a circuitous rock-and-roll triumph. The El Paso band released their first record in 1996 on a tiny punk imprint, then followed it up two years later with an album on a slightly larger label. By 2000, the group was poised for a breakthrough, releasing the seminal Relationship of Command on Grand Royal Records, a label owned by the Beastie Boys. That album catapulted the band to radio play, appearances on late-night TV, and had them booked as the opener for a tour co-headlined by the Beasties and Rage Against the Machine, which ultimately never materialized. The influence and legacy of Relationship of Command casts a long tail, but the band broke up the following year.

I lived in McAllen when Relationship of Command came out, and was involved in the punk rock scene in the Rio Grande Valley at the time. The album inspired all of my friends who weren’t already in bands to start one, and changed not just the sound of what sold (pop-punk was out; melodic, aggressive hardcore was in) but also what bands believed was possible. Before At The Drive-In, the most you could hope for was playing a quinceañera hall or the VFW to a couple hundred kids who turned out because touring bands almost never came down to the Valley. After At The Drive-In, touring, making records, and having dreams that your music could matter was suddenly a thing.

The Valley and El Paso are far apart, but they’re both remote places where kids—especially English-speaking Latino misfits with creative ambitions—don’t have many role models to look to as examples of success. There’s a message you get from a young age there: The things you dream about, they don’t happen to people who come from these places. If you grow up in New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles (or even Austin, Houston, or Dallas), you get a different message about possibilities.

So At The Drive-In mattered to a lot of creative kids in border communities more than any other band ever could. But they also impacted the world at large. When the BBC wrote in 2010 that they “would send shockwaves through the forthcoming decade, influencing innumerable acts and topping critical lists the world over,” they were speaking to what At The Drive-In meant to people who couldn’t find El Paso on a map. (The band’s t-shirts helpfully pointed it out to them.)

The band broke up in 2001 for personal reasons, essentially splitting into two: lead guitar player Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala formed The Mars Volta, and rhythm guitar player Jim Ward, bassist Paul Hinojos, and drummer Tony Hajjar started a band called Sparta. The latter sprinted out to a certain kind of early aughts indie rock stardom—they toured medium-sized clubs and had songs that placed in the middle of the modern rock charts over a five-year period. The Mars Volta took another year to release its first album, but it catapulted the band to a higher level of rock stars. It headlined festivals and toured arenas. When it served as an opening act, it was in stadiums with bands like the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The Mars Volta was a great band—but it didn’t scratch the same itch as its predecessor.

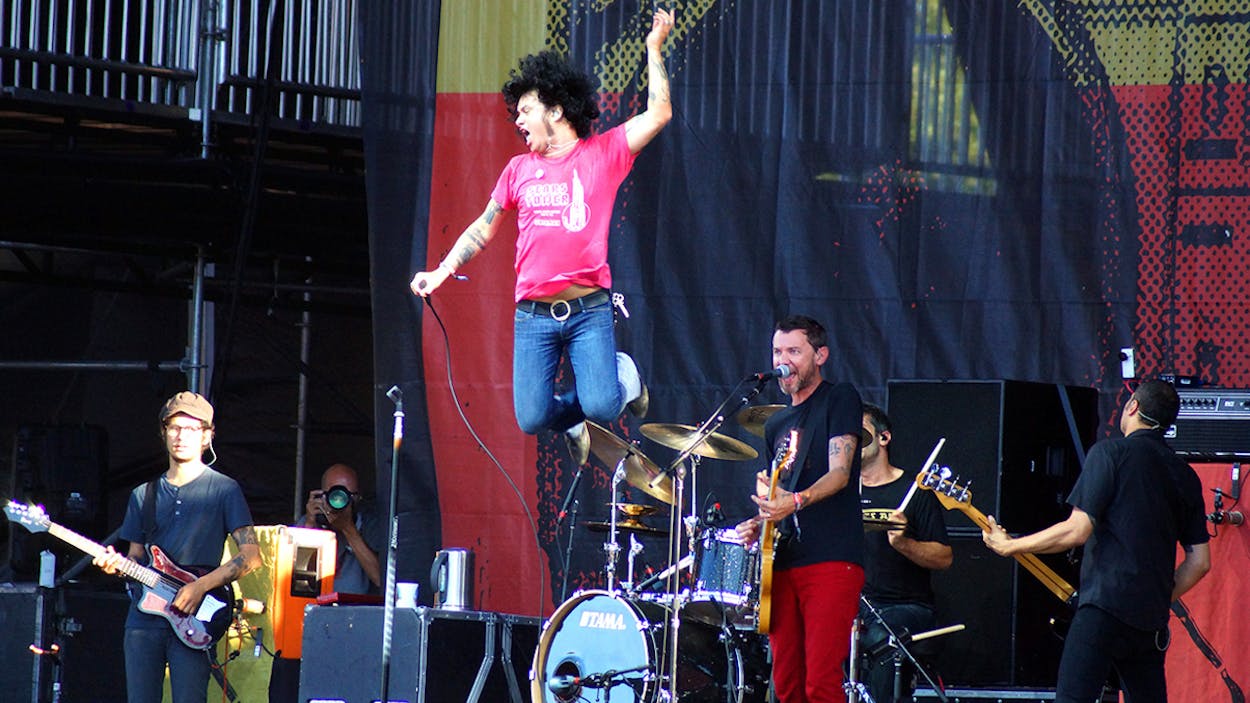

So when At The Drive-In announced a brief reunion tour in 2012, it was exciting news. The band never took a proper victory lap around the U.S. when Relationship of Command came out, which meant that people who never heard “Arcarsenal” or “One-Armed Scissor” live would finally get the chance.

That tour ended up being weird, though. The band played a series of warm-up dates in Texas—four club shows in Austin, Dallas, Marfa, and El Paso—before a handful of festivals: Coachella and Lollapalooza in the U.S., Reading and Leeds in the UK, Fuji in Japan, Splendour in the Grass in Australia, and FIB Benicàssim in Spain. But that was it. Bixler-Zavala told Spin the year after the reunion that it “wasn’t really the raddest reunion we could have had,” and made a reference to the stage performance including “some people not looking like they wanted to be there.” That was a frequent point of criticism of the performances, in fact—Rodriguez-Lopez’s body language didn’t belong to someone who was excited to be playing those songs on stage. In interviews after the reunion was finished, he later said as much:

At the Drive-In as it was is of no interest to me. I am interested in the five people in the group, because the chemistry between the people…that’s the music. What ends up on a record or on a stage is a result of that chemistry. That’s the thing. I’m interested in being around those guys. I have absolutely no interest or emotional connection to playing songs that I wrote when I was 18 to 23 or whatever. The only emotional connection I have is that I see that it makes people happy when I look out there, people who were way too young to have seen us live when we were actually around. That’s an amazing thing in and of itself, and I don’t want to sound ungrateful for the amazing situation I’m in that people care about something we did 11 years later, but I have no emotional connection to it, because the person I was then has died about three or four times since then.

That’s an honest answer to a tough question—but it also explains why the At The Drive-In reunion that was announced on Thursday morning is exciting even to people the people who witnessed a reunion that “wasn’t really the raddest” four years ago.

At The Drive-In announced Thursday that, in addition to a world tour, they’d be releasing new music in 2016. That’s a big deal. Certainly other bands have reunited to release new music with both terrific and uninspired results, but the circumstances of At The Drive-In are fairly unique. While they haven’t recorded music together since Relationship of Command, the band’s members have had a creative life together over the years—whether it be Sparta or the Mars Volta—and more importantly, there’s power in bringing people whose shared life experiences stretch back as far as the members of At The Drive-In do. Omar Rodriguez-Lopez has made plenty of music over the last fifteen years, but the chemistry that comes with being in a room full of people who’ve known you since you were a teenager, and who are making music under a name that belongs to everyone, is something that opens creative possibilities that didn’t exist for the other projects.

After the 2012 tour, Rodriguez-Lopez made headlines for saying that there wouldn’t be a new At The Drive-In album, and that it was “more of a nostalgia thing,” speaking frankly about the money involved. But its impending reality shows possibilities for the forthcoming tour (which, while it has yet to announce any Texas dates, is probably going to include some time in the band’s home state at some point—perhaps including a SXSW warmup?).

At The Drive-In matters in part because their rise meant so much to so many people—especially on the border, but also to people who saw and heard themselves reflected in the opening rumble of “Arcarsenal” or the slow burn of “Napoleon Solo”—but also because they left so much unfinished when they split. The fact that even their last reunion was so short, strange, and honest that it flew in the face of the usual reunion cash-in tour just added to the myth. At the very least, At The Drive-In is something that matters too much to these guys to fake it, which is also how their fans always felt.