One humid day last summer, when most teenagers were on vacation or at camp or slaving away at tedious jobs, a burly, flirtatious nineteen-year-old named Raymond was locked inside a small, frigid metal building with five other boys to whom he could relate. Two years earlier, Raymond had smashed a friend’s face in with a lead pipe, and now he was confined at the Giddings State School, a juvenile detention facility one hour east of Austin. Leaning back in his chair, Raymond told the group about his upbringing. He talked about competing with his cousins for his mother’s attention. His father, a sharp dresser known for violent outbursts, had never been around; Raymond saw his namesake for the first time in a grocery store when he was about five years old. No one flinched as Raymond told his unhappy story. They had already heard Chuong, a capital murderer, tell how his mother condemned his stealing only when a television he’d looted wasn’t big enough, and Kenneth, an expert carjacker, describe being made to fight as a child in backyard matches while relatives placed bets on the outcome.

As the other members of the group encouraged him, Raymond recalled a rare instance when his father had joined an elementary school field trip and helped him plant a mustard seed. It came as no surprise to him or his audience that even this cheerful story had a violent conclusion. As Raymond told it, when his mother heard from another school parent that his father had dropped in on the class trip, she became furious. “She grabbed my leg and started hitting it with a belt,” he said. “It was black, with beads on it.” Soon she was beating his chest as well. Shortly thereafter, Raymond’s father showed up at the house, only to be attacked on the front lawn by Raymond’s uncle. “His nose was bleeding, and I wanted to help but I was stuck,” Raymond told the group. “I stayed on the couch and I was scared. My grandma asked why I was holding my chest, and I showed her and told her why. She asked my mom, ‘What the f—’s wrong with you?’ and my mom said, ‘I’ll do whatever the f— I want with my kids,’ and then I heard a punch. I was scared. My mom had a little vase, and my grandma hit my mom over the head with it—boom!”

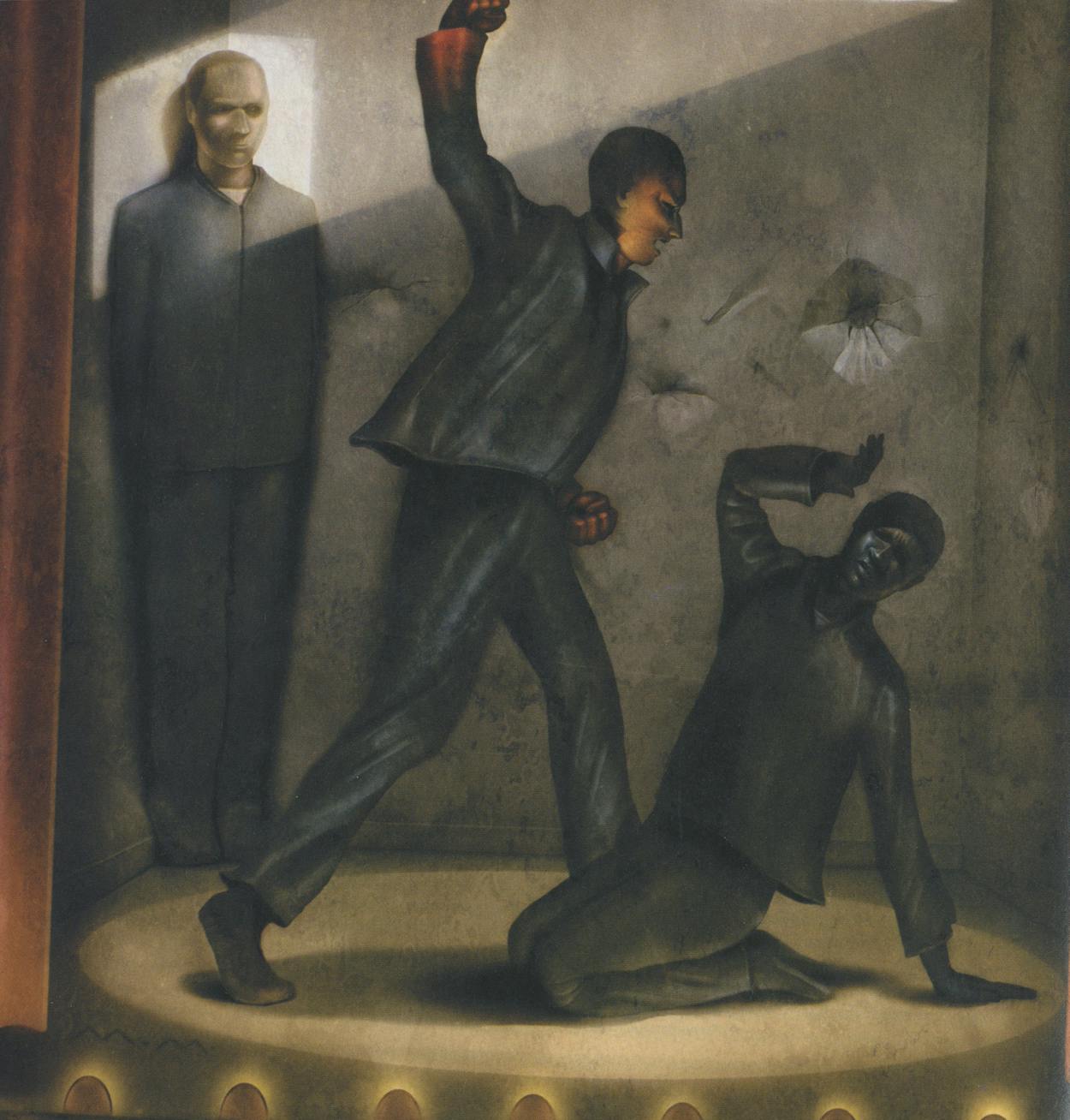

Raymond and the other boys were members of one of the most unusual rehabilitation programs on the juvenile detention landscape. They had all been arrested as minors and sent to Giddings, where their good behavior and a desire to reform had earned them admission to the Capital and Serious Violent Offenders Treatment Program. The CSVOTP is a form of group therapy that attempts to rehabilitate young offenders with a kind of improvisational theater. Twice a week for about six months, participants in the program attend hours-long sessions during which they examine and then dramatically reenact the defining moments of their lives—including the crimes that brought them to Giddings. These sessions are often unbearably intense, leaving the boys emotionally and physically drained, covered in sweat and tears. But a positive evaluation from program therapists Margie Soto and Thomas Talbott can mean the difference between early parole and hard time in adult prison. In the case of boys like Raymond, serving four years for assault with a deadly weapon, the program attempts to create healthy members of society by transforming violent, even homicidal tendencies into a capacity for empathy.

This preposterous-sounding ambition may not find taxpayers celebrating in concert. Why, you might ask, am I paying tax dollars to fund a drama camp for murderers? According to the Texas Youth Commission, you can’t afford not to. After all, depending on a court’s decision, these boys may soon be your neighbors. While the graduates’ long-term success is never guaranteed, the three-year marker used to evaluate a program’s strength shows a startling reduction in recidivism rates: Graduates are 49 percent less likely to be reincarcerated for a felony than peers who have not been through the treatment—a significant enough finding to prompt the Department of Justice to cite the CSVOTP as a model program.

For Soto and Talbott, however, success is measured on a smaller scale. Having found their way to a particularly difficult memory of Raymond’s, the therapists prepared for the second half of his session, in which Raymond would be made to reexperience the pain. Recalling the fight between his mother and grandmother had visibly upset him, and tears were now streaming down his face. Talbott, a forty-year-old with a goatee, dimmed the lights, the cue that it was time to begin a dramatic scene. Most of the boys filed out to assume their roles, leaving Raymond in the room with Chuong, who had shown himself to be one of the group’s most intelligent members (at the request of Giddings officials, the juveniles’ names and minor details of their crimes have been changed).

Chuong pushed his chair close to Raymond’s and wrapped an arm around his large, muscular shoulders. For about ten minutes, he whispered in Raymond’s ear, keeping him focused until the others returned. Out in the hall, Soto, a petite, no-nonsense 46-year-old, had cast Kenneth in the role of Raymond’s father.

“I came to see you today,” Kenneth said, establishing the theatrical episode. “You have a field trip. I want to see you.” Raymond stared at the floor. “Let’s have fun,” Kenneth said, rubbing Raymond’s close-shaved head with an open palm. “Do family things like father and son.”

Suddenly, Raymond’s mother, played by a middle-class math whiz named Justin who was in for hog-tying and pistol-whipping a man while robbing his house, butted into the scene, demanding to know if Raymond had seen his father. Talbott took care of the sound effects, snapping his belt against a chair.

“You ain’t got no daddy!” Justin yelled. “He nobody. I done everything for you!”

Playing the grandmother, Mauricio, a seemingly polite kid from the border who had beaten his uncle to death with his bare hands, wandered by and asked, in a hoarse, sweet voice, “What you doin’ with my boy?” Raymond’s face took on a pleading expression as the two teenage boys began to re-create the fight between his mother and grandmother, whose name—Bea—Raymond had tattooed on his arm. He seemed to be losing himself in the scene. When Justin and Mauricio tumbled to the floor, the other boys, Soto, and Talbott had to leap in to restrain him.

“Get off my granny!” Raymond shouted. “I hate you! You ain’t never let him be there! You pried him away from me!”

The boys were strong, but in this state Raymond was more powerful than all of them combined, and as the fight intensified he appeared to get angrier, tossing them off his back as if they were half his weight. The six of them began sweeping around the room as one unit, knocking into the walls, legs and arms flying out in all directions. At some point the boys managed to push Raymond back and hold him tight against the wall. He struggled to catch his breath. They braced for an eruption that never came. Raymond’s sweat-soaked body went limp, and he collapsed on the floor.

The boys huddled around him, and Kenneth tenderly brushed the top of his head. Tears dripped onto his light-gray T-shirt. Chuong grabbed some tissues and laid them on Raymond’s lap, and when Raymond didn’t react, Chuong wiped his face for him. Still, there was no reaction, so Chuong placed his arm around Raymond’s neck. As Raymond’s head fell against Kenneth’s shoulder, the group sat in silence.

“Thank you, guys,” Soto said.

“You were all very good today,” Talbott said.

EVERY YEAR THE TEXAS JUVENILE justice system receives referrals for about 75,000 kids, the vast majority of whom have committed minor offenses such as shoplifting, vandalizing property, or selling their own Ritalin. These kids are usually released and made to meet with a parole officer, but those who have been convicted of more-serious crimes (about 3 percent of the total number of juveniles arrested) are committed to one of several facilities the Texas Youth Commission runs around the state. The most dangerous kids are sent to Giddings.

In 1988 the TYC asked then-director of psychology at Giddings, Linda Selness Reyes, to help design a curriculum for juvenile murderers incarcerated there. Like many of the school’s charges, Reyes had grown up in a poor neighborhood, and in the graduate program of the psychology department at the University of Texas at Austin, she was studying the powerful influence of environmental conditions on human behavior, including criminal behavior. Juvenile crime had escalated in the eighties, and the TYC was driven by a sense of urgency. At that time, no juvenile offender could be transferred to adult prison; all were released by age 21. (More sentencing options are now available.)

“We didn’t have a lot of resources,” she told me. “I was the only therapist out there. We had to figure out a way to get to them. Fast.”

Reyes, a commanding and maternal woman who is now the deputy executive director of the TYC, found that the majority of the kids convicted of homicide were deemed mentally competent by the courts, yet few facilities had developed solid approaches to behavioral treatment. She knew that to truly reform the youth offenders in her care, she needed them to recognize the enormous tolls that their actions had taken, but she also knew the perils of focusing entirely on these acts of transgression. She believed that successful rehabilitation hinged on a youth’s ability to acknowledge the pain inflicted on him by others, without using those emotions as excuses for the havoc he had wrought.

Borrowing from various therapeutical methods, including psychodrama, which uses role play to explore emotions, Gestalt, and other cognitive behavioral approaches that stress personal responsibility, Reyes designed a program that would work within the context of the school’s resocialization curriculum of academics, behavior modification, and correctional treatment. In a group setting, each offender would discuss events from childhood and early adolescence that led to his or her misbehavior. Following this narrative session would be a role-playing session, in which the group would act out key events the student had described. All this would be known as the “life story.” Then, after each student had taken a turn, a cycle of “crime stories” would begin, employing the same pattern of narration and reenactment in order to bring each student face-to-face with his crime—once from his own perspective and once from his victim’s.

Starting with a group of eight boys, Reyes progressed tentatively; almost immediately, she saw encouraging signs from her students. According to her observations during the first years of the program, 84 percent of the juveniles were able to reconnect with some basic level of empathetic concern for their victims. Over time, the positive effects the program seemed to have on recidivism rates won supporters throughout the state’s criminal justice system. And not only did the CSVOTP produce results, but it cost very little to implement.

Today, the CSVOTP is an exemplary program for the TYC, and juvenile justice experts from all over the world frequently tour the Giddings facility for a chance to witness the unique treatment. Earlier this year, an advocacy group in Colorado petitioned legislators to redesign the state’s juvenile rehabilitation programs in the image of the Texas system, making particular mention of the CSVOTP. If the Colorado group prevails, it would mark the first time that Reyes’s program has been implemented outside the state of Texas. Despite nearly twenty years of success, no other juvenile detention facility in the country hosts a program quite like the CSVOTP. Most states either confine their youth offenders to adult prisons or send them to juvenile halls, where they receive far less rigorous forms of therapy. Those familiar with the Giddings system have been known to suggest, without judgment, that perhaps some juvenile counseling professionals are simply happier to meet with a client one-on-one in an office than endure hours of intense psychodramatic role play while locked in a room with a group of crying and screaming murderers.

AS THE SUMMER WORE ON, young swallows chirped eagerly around the lush, tree-dotted campus, which looked more like a private school than a prison, causing a racket audible through the two sets of doors leading to the group room where the boys met. Every Tuesday and Thursday they assembled outside their sparse, white-walled dorm, where they slept side by side in an open bay. They marched through the baking morning sun past old stone buildings with copper roofs weathered mint green and descended into the group room with its walls marred slightly by fists and elbows. There they formed a circle of gray plastic chairs and sat in silence, waiting for Soto and Talbott, putting on silky black snap-on jackets as they adjusted to the blasts from the air-conditioning vent above.

Since May, I had been watching the boys, with their consent, from behind a one-way mirror. I had heard them tell about the trauma they had endured—the brutal beatings, the abandonment, the parenting that trained children to fight like pit bulls. But I had yet to learn the details of their crimes. When I asked Talbott, he said he usually postponed learning the specifics himself, explaining that during the life story sessions, he needed to be sympathetic, and knowing each boy’s violent history often made that difficult.

Soto, for her part, was confident about the upcoming crime story sequences. “They’re getting to that point where they can be heartbroken and still love,” she told me. Raymond, in particular, had been struggling admirably with his feelings toward his mother. “I still love her,” he told the group one day. “But I hate her for the things she did.” Soto reassured him that his feelings were normal. “I want to understand why,” Raymond said.

“We may never find out why,” Chuong said.

Before the sequences began, Soto gave the boys an opportunity to ask me questions. They were curious to know what I had been writing in my notebooks, and in my reactions to their stories they seemed to look for hints as to what the reactions of future neighbors and girlfriends and employers might be. Raymond put it plainly. “What do you think of us?” he asked me. “Will that change once you hear what we done?”

I told him I didn’t know. He stared at the floor, unsure of how to put his next question.

“Does that mean, like, if we saw you out in the free world, you would still say hi?”

Chuong told his crime story first, since his was the case under most urgent review. Before his upcoming twenty-first birthday, Chuong would go before a judge who would decide whether he’d serve anywhere from ten to forty years in adult prison or get released on parole. Based on the outcome of Chuong’s sessions, Talbott and Soto would advise a review board, which would in turn make recommendations to the judge. Chuong was smart, and he’d done well in the academic areas of the Giddings curriculum, where he’d earned a GED, but the therapists felt that until recently he hadn’t been putting much effort into his rehabilitation.

Normally, a student finishes his crime story within a session or two, but Chuong’s criminal history was so lengthy, and his memory so colorful, that it was four sessions before he finally staged the crime for which he’d been committed. He recalled practice-shooting at trees in the woods, learning about sex from porn movies on TV, and as a fourth-grader, transporting cocaine in his backpack for his uncle. Later, in high school, he sold the drugs himself. Sometimes, if a drug payment was late, Chuong would shoot delinquent customers in the legs so they’d remember him whenever they tried to walk.

This reckless idyll came to an end one night when a friend said he needed money to pay some outstanding debts. Chuong suggested they rob a bakery; in fact, he already had one in mind. He took a gun and told his friend to ask for the cash, and the two headed out. At the door of the bakery, they paused.

“I said, ‘Ready?’” Chuong told the group. “I opened the door, ran into the store, and had the gun up already. I didn’t see anyone at first; I thought it was closed. I went to the cash register, and that’s when my victim came out. I got excited. I said, ‘Give me the money, motherf—er!’” As soon as his friend had gathered the large bills, Chuong pulled the trigger and shot the woman dead.

It didn’t take much, after such a buildup, to get Chuong into his role. Perspiration beaded on his face as the group filed out and the lights were dimmed. Alone, he gulped and sniffled for several minutes until the boys returned. Carlos, a bashful new immigrant who’d unloaded nine rounds at a rival gang member (and missed), had been cast in the role of Chuong’s friend. He walked up and said he needed money.

“I got a gun at my house,” Chuong said, his body beginning to shake.

The two began to march back and forth across the room in lockstep, pretending to walk to the bakery. As he marched, Chuong sank into the scene, and the polite, intelligent expression I was used to seeing on his face gave way to cold intention. Kenneth, as the doomed baker, stood alone, pretending to wipe a counter.

Suddenly Chuong walked up to him and screamed, “Give me the money, motherf—er! All of it!” Kenneth held up his hands, but Chuong pretended to shoot him, shouting, “Boom!” As Kenneth fell to the ground, groaning and clutching his stomach, his assailants darted to the other side of the room, where Chuong began to twitch uncontrollably, like a cat doused with water.

“I didn’t do anything,” Kenneth whimpered, rolling around on the floor. “I didn’t even look.”

Talbott placed a photograph of the crime scene in Chuong’s hands and made him look at it while the other boys gathered around. “That lady has kids,” Raymond said. It was difficult to tell whether Chuong truly recognized the horror of his actions. Returning to the scene of his crime had only seemed to make him angry. He gritted his teeth and struggled to push out the words “I’m sorry.”

Soto took a mental note of Chuong’s response. Though the psychodramatic sessions have strong rehabilitative value, they also give therapists a chance to diagnose a student’s progress. In the heat of the moment, will he show an ability to empathize with his victim? This question was foremost in Soto’s mind as the boys rearranged themselves for the second part of Chuong’s crime story reenactment, in which he would play the victim.

For the role reversal, Kenneth took the part of Chuong. He demanded the money, Chuong pretended to give it to him, and Kenneth yelled, “Boom!” Instead of falling to the ground, however, Chuong walked away toward the wall. He seemed startled, unsure of himself. Soto was able to coax him down to the floor, where he made a halfhearted show of dying.

“You hurting now!” Kenneth yelled at him. “Look at your bitch ass!”

Chuong stared up at his attacker. Without much emotion, he asked, “What happens to my family?”

The scene was over. Talbott turned the lights up, and Soto motioned for the boys to sit in a circle, but Chuong stayed on the floor for a long time, staring at the white foam ceiling tiles. While he lay there, the group discussed his session. Kenneth offered that Chuong’s apology to him had felt so meaningless it was as if he’d been shot twice. “He still has that rage,” Kenneth said. “He’s still angry.” Chuong ripped open the snaps on his jacket but didn’t respond.

“Chuong,” Soto said, “you didn’t successfully pass this session.”

A VIOLENT JUVENILE in the midst of a rehabilitation that connects him with new, empathetic emotions is at a severe disadvantage should he wind up serving hard time in the less hospitable surroundings of adult prison. He may have let down his guard, spilled his guts, and done everything asked of him only to have his recommendation for parole be denied by a judge. “We’re asking the kids to change,” Soto told me, “and if a kid goes to prison, that change is going to hurt him. Sometimes we ask ourselves, ‘What the hell are we doing? Are we opening him to danger?’ We tell those who are transferred to prison to modify—they may have to put these tools aside for a while. But we ask them not to forget.” After ten years of experience with the program, her refrain to all the kids has become “Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.”

The motto pertains equally well to those who get out. Release is addressed constantly at Giddings, where students are instructed to provide a “success plan” that details where they will live, how they will make money, and how they will avoid bad associates and habits. But the numbers provided by the TYC’s research director, Chuck Jeffords, show that even flying colors from the CSVOTP and a foolproof success plan are no match for the pressures in the neighborhoods to which graduates return. While the three-year recidivism and rearrest rates for the program have always been impressive, it turns out that after ten years, the graduates’ improvements practically wash out. I had been told by others in the juvenile justice field not to expect the CSVOTP to be a magic bullet, but the long-term findings were still worrisome. Forty percent of the program’s graduates are reincarcerated within a decade of release. This is only 5 percent less than the numbers for a control group of juvenile offenders who have not undergone the treatment. And most of the offenders at Giddings would be mingling with the public for much longer than a decade: Even teenage capital murderers facing forty years in prison (the maximum sentence under current law) would be back on the street by the time they turned sixty.

When I brought these apparent failings to Reyes’s attention, she was unfazed. She offered an analogy, suggesting that if a gunshot victim receives surgery at a hospital only to return to his neighborhood and get shot again, no one blames the doctor. “Is the original surgery responsible for the second wound?” she asked.

It is a difficult point to dismiss. The recently released begin an awkward dance with a reluctant public when they land back in their neighborhoods, and the TYC can do only so much to make it smoother. “There is no way TYC can stay in these kids’ lives for five to ten years after the fact,” Reyes told me. “They will be beyond the age where we are responsible for them. Communities have to change while kids are changing. They have to be able to go back to a place where there have been community-wide efforts to suppress the gang activity, where schools are inviting them back in, where there are local people willing to accept responsibility for continuing to provide guidance and opportunity to kids who have made changes while they were in an institution.”

Of course, many would argue that violent criminals should simply be locked away for as long as possible. The idea of rehabilitating young capital offenders as an alternative to incarcerating them for long sentences has been known to stir up strong emotions. Ten years ago, when a support group for victims’ families heard about the CSVOTP, they were livid. They drove down to the school as a group and confronted the staff. A tense meeting ensued, with the therapists on one side of the table and the enraged families on the other. Judy Nesbit and her husband, Ric, sat with the families; their daughter had been killed by two teenagers a year earlier. Judy recalled the families’ position as, essentially, “We can’t stand for this.” But after several conversations, many of them began to change their perspectives, and some began making annual presentations to the boys about the terrible chain reactions that result from a violent crime. Their feelings, however, remain conflicted. This year, when Judy spoke to the group, she admitted that while she supports the philosophy of rehabilitation, she was still thankful that the two boys who killed her daughter went to “big-boy prison.”

“I don’t have much feeling for those two except I want them in prison,” she told her audience. “No conscience, no remorse. They don’t have to do that where they are. They just make it through the day. From what I hear, the prison doesn’t have a rehab program.”

As tough as adult prison is compared with a place like Giddings, the strange truth is that for some of the youths, it offers the promise of a family reunion. Above Talbott’s desk a bumper sticker reads “My Child Is an Honor Student at the State Correctional Facility,” a reference to the staff joke that for some households, Giddings is high school and prison is college. Like a Yale legacy, a juvenile with a parent imprisoned at Huntsville may find it easy to follow suit. The state school’s acting superintendent, Stan DeGerolami, who’s spent more than twenty years working at the school, has begun to encounter this disheartening generational pattern. I’d heard that he had recently been approached on campus by a young female offender whose father, now in prison, had attended Giddings in the late eighties.

“That had an impact,” he told me, when I brought it up. “Here we are working with the children of students we worked with in the eighties? It’s hard not to feel like you’ve failed. I wonder if there’s something else we could have done. But apparently this young man didn’t take advantage of what he learned here.” He sighed and mumbled that he knew there were a thousand other factors involved in the man’s troubles, but his mood had grown sour. “Thanks for bringing up one of our failures,” he said.

A job with the TYC provides no shortage of disappointments. Resources are undeniably short, and the stress has, at times, led to troubling incidents. This spring, after a number of million-dollar lawsuits that accused guards of abusive behavior, the TYC’s executive director, Dwight Harris, explained that the low-paying agency had encountered challenges finding, training, and retaining staff in rural areas. Compounding the matter, the displacement of hundreds of youths confined to facilities affected by Hurricane Rita increased the demands on staff at the remaining schools.

The problems have hit hard at Giddings, where Soto and Talbott frequently work overtime to accommodate additional students. Last year eight psychologists populated the department. By midsummer that number had dwindled to four, and two new employees training for the CSVOTP weren’t sure they wanted to make the same commitment Soto and Talbott had made. The absurdly challenging proposition of the program doesn’t appeal to most child-loving social workers, especially when the pay hovers around $35,000 a year. After watching a particularly disturbing session, one troubled trainee told me, “It isn’t the kids; it’s reading what they have done.” Shortly thereafter, she quit. A few weeks later, Talbott announced that he would soon be moving out of state, far from the program’s heavy responsibilities.

Unfortunately, the strategic plan for 2006—2007 doesn’t contain much that would persuade employees like Talbott to hang around. Cuts in state and federal funds are forcing many facilities to eliminate programs. Without the resources to give every offender the specialized treatment he or she requires, schools like Giddings are being compelled to prioritize rehabilitation based on severity of crime and risk to reoffend. Reform advocates and TYC proponents alike support a decrease in the number of kids in the system, but for the time being, counselors make due with limited means.

They do have one thing for which to be grateful. In recent years, the number of juvenile arrests for violent crime in Texas is down significantly from the spike of the nineties, hovering just under four thousand annually (although the numbers are beginning to trend back up). Each of the past few years, the number of young homicide offenders has been around fifty, back to the same number as twenty years ago, a great enough reduction that the CSVOTP can now include other offenders just as dangerous as those who succeed in killing their victims, such as armed robbers and carjackers.

In the end, therapists look to reduce the number of future violent offenders by way of the students in their care. Two of the boys in last summer’s class already had children of their own, children who would feel the ripple effect of their fathers’ abilities to absorb the program’s lessons. The boys often wondered aloud about their kids’ futures and what role they might play in them. But since both had come from fatherless homes themselves, these thoughts required them to take a mental leap toward an unreal world. The rehabilitation program at Giddings could help prepare them, but they would have to make the jump themselves. Chuong summed up the nature of the struggle one day when he asked, “How can I become something I never knew?”

RAYMOND HAD OPTED to wait until everyone else had gone before he presented his own crime story. Summer had passed, and fall brought with it a high school football season in which he was now too old to participate. As the day of judgment approached, his thoughts swung back and forth between the lessons he was learning at Giddings and the hostile world outside in which he’d have to make them stick. Reflecting on Chuong’s failure, Raymond wrote, for his required “journal assignment”: “When Chuong was role-playing he did his part of the crime very good. He liked the part of being the bad guy but when it came to him to show feelings for a woman that’s no longer living because of the hands of him he had none . . . I wish things would have been different for Chuong. He needs to find his self and his feelings.” Raymond had become one of the group’s most supportive members, but some things still remained outside his control. One day, following a session in which he’d said nothing, he explained to me: “This is the anniversary of my granny’s death, and two friends just died. One got shot in a drug deal two weeks ago, and one got shot two months ago walking down the street.” His expression of deep sadness acknowledged a hostile reality no state-funded program could transform. For Raymond’s nineteenth birthday, his second one in confinement, Soto had tried to lighten the mood with some mini Twix bars. The boys savored every bite. “It’s all downhill from here,” she told Raymond, teasingly.

Raymond basked in the attention, turning it back on Soto with a flirtatious smile as he asked, “And how are you doing today?”

“Well,” she said flatly, “yesterday I got a call from a kid who thanked me for not transferring him to prison. He thought about what we’d talked about when he was locked up. He has five kids now; he’s married to the same girl. Twenty-eight years old. He called me before that, after the first baby. Yesterday would have been his first day out if he had been transferred to prison instead of paroled. He thanked me for whipping him into shape.”

Although Raymond had expected his crime story to take the usual two sessions—“I don’t have much to say,” he explained, “just the same type of fight over and over”—three sessions filled quickly with recollections of smashing people’s faces into basketball poles, water fountains, and pavement. The stories revealed a tendency on Raymond’s part to pummel his adversaries until they were immobile, and Soto explained to him that he clearly needed to work on his low self-esteem so that a perceived slight wouldn’t trigger these explosions of uncontrollable rage. She drilled him on this point until he began to recognize how dangerous he really was.

“I know I could kill someone if I couldn’t stop,” he said. “It’s scary, Miss.”

Raymond had been selling drugs to assist his mother with $500 of rent every other month and to buy himself stylish clothes for school, but he told the group that his bad behavior had often been overlooked because of the social status he enjoyed as a football player. One day, when he was seventeen, he was walking from a drug deal when he saw a For Sale sign on an old Lincoln. Raymond already owned a 1993 Honda Accord, but it was in the shop getting extravagant rims installed, and the idea of a backup car appealed to his sense of importance. After counting the $1,600 he had in his pocket from his recent transaction, Raymond handed $600 over to the man in possession of the Lincoln, an acquaintance named La-La, and drove away.

Two weeks later, Raymond was driving the upgraded Accord when he stopped at the house of a friend named Terrell to pick up some drugs. During the visit it came out that Terrell was the Lincoln’s original owner. He’d sold it to La-La the previous month but had yet to receive any cash; now that Raymond had the car, Terrell perceived this outstanding debt as Raymond’s responsibility.

“He came up and said, ‘Pay me what you owe me,’” Raymond told the group. “And I say, ‘What you talking about? You know I paid.’ And he got mad and started cussing.” The pivotal moment came when Raymond’s cell phone rang. It was his mother, asking him to pick up a cake on the way home. Terrell made a disrespectful comment, and tempers escalated until Raymond found himself vowing to return with a gun and “shoot the house up.”

“You never wanted to shoot anybody before,” Soto pointed out. “Why now?”

“He said ‘Go get that bitch her cake’ about my mom!” Raymond said.

Soto probed a little deeper and found another motive. Raymond admitted that, in part, he was afraid. Terrell had told him, “I’m gonna get you wherever you are,” which Raymond interpreted as a death sentence. Never one to react to fear by hiding, he stormed home, intending to retrieve an AK-47 he kept in his brother’s room. The door was locked. Undeterred, he hugged his mom, telling her, “I’m gonna be gone a long time.” Then he drove back to Terrell’s house, where he planned to fight him. Raymond’s brothers, having been alerted to the situation, pulled up behind him and dragged him into their car. As Terrell approached, Raymond saw a lead pipe near the seat and grabbed it.

“I came out of the car with it,” Raymond said. “He stopped and said, ‘Damn.’ I said, ‘You f—ed up,’ and chased him. I threw the pipe and it hit him and he fell and I got on top of him and started punching him.”

“Did his head hit the concrete?” Justin asked.

Raymond nodded.

“How many times did you punch him?”

“About thirty,” Raymond said.

“Was he moving?” Kenneth asked.

“His skull was crushed,” Talbott said.

“Where did you hit him?” Carlos asked.

“In the face,” Raymond said.

“Why did you keep fighting him?” Soto asked. “You usually quit when they’re down. He wasn’t saying anything or moving. Were you saying anything to yourself?”

“Nothing,” Raymond said. “I didn’t even see nothing. I didn’t say anything to myself until I got up. Everything was blank when I was punching.” Raymond seemed shaken by the memory, but the therapists didn’t let up, confronting him coldly with the facts of the medical report.

“They had to pick the bone out of his brain,” Soto said.

“Cut away the dead brain material,” Talbott said.

“You broke his nose,” Soto continued. “And his nasal cavity caved in. There was no way he could do anything after that first blow. And you kept punching. There’s things he won’t ever be able to do again. Things he had to relearn, like how to walk. Did you ever think of that?”

Raymond was crying now. Talbott motioned for the boys to stack their chairs in the corner. As they exited the room, he dimmed the lights. Raymond sat motionless in his chair, holding his head in his hands like a stone statue.

When they filed back in, ten minutes later, Chuong opened the scene. “Check out this car of Raymond’s, man,” he said.

“It’s cool,” Justin said. Kenneth walked up and threw his arms around Chuong in a bear hug.

“You see that car?” Chuong said. “Look at those rims!”

“Whose car is that?” Kenneth asked. He was playing Terrell.

“Raymond’s car,” Chuong said.

“That guy owes me money,” Kenneth muttered. “Bitch-ass n—er. Where he at?” He walked over to the spot where Raymond was still sitting in the chair. “You got money to pay for two cars?” he yelled. Raymond didn’t budge. “Come on, man. You pay me for this car.”

“That’s La-La’s car,” Raymond said quietly.

“What?” Kenneth asked. Chuong put a foot-long cylindrical piece of foam in Raymond’s hand, and Raymond began breathing harder. As Kenneth continued yelling, Chuong elbowed Raymond and said, “He’s trying to get you.”

“F— that bitch,” Raymond said, finally rousing to the scene. “I’m gonna get him ’fore he get me.” He dived at Kenneth, throwing the foam at his head and knocking him down. He hit Kenneth once in the face before he caught himself and pulled his punches, slapping his hands above Kenneth’s face until the boys tackled him from behind. Though he was clearly strong enough to drag them around, as he had before, Raymond allowed himself to be shoved over to the opposite side of the room.

“He take me for a ho!” Raymond said.

“He’s unconscious, man!” Justin said, crouching over Kenneth’s face.

“Someone get an ambulance!” Chuong shouted.

“He wouldn’t listen,” Raymond said. “I felt weak.”

“Look at your hands,” Soto said, touching Raymond’s knuckles. “Look. You’re all cut up. You beat his face in!”

“I’m scared,” Raymond whispered in Soto’s ear. “I’m scared.”

Soto was satisfied with his reaction, but the real test of empathy comes when the protagonist assumes the role of his victim. To start this scene, Kenneth, playing Raymond, tossed the foam at Raymond’s head before leaping on top of him and throwing him to the ground, where he pretended to punch him in the face repeatedly. Instinctively, Raymond flexed for a second, then released his tension and let Kenneth continue. He closed his eyes and lay still as Kenneth shouted in his face, “I told you! F— you, n—er! I don’t pay you for shit! F— that shit.”

“You can’t move,” Soto whispered in his ear. “You’re paralyzed. Nobody can stop him and nobody is going for help. You’re having trouble breathing now.” She asked him to respond to his attacker.

“You crazy,” Raymond said, his eyes still closed. “You don’t listen.”

If Raymond showed pity for himself, as Chuong had done, she was prepared to cut him off, but with Kenneth sitting on top of him, staring him in the face, Raymond began to evaluate his younger self.

“Why you do this?” he asked Kenneth. “You don’t care about nobody. It don’t make sense.”

“I’m sorry,” Kenneth said, almost mockingly. “I know I got to change, but it keeps coming back.”

Talbott turned the lights down even lower so that the room was almost completely dark.

“You got to change,” Raymond said to the figure pinning him down. “You can’t do that to people. You better change the way you think. The way you see. You get mad, and it didn’t have to go like that. It wasn’t right. You gotta think before you get mad.”

The scene was over. Raymond stayed on the floor, looking at the ceiling. Tears ran down his cheeks.

“How do you feel?” Soto asked him.

“Dizzy,” he said.

“What else?”

“I hurt someone. I didn’t want to see that in myself again, but I didn’t listen.”

Talbott asked him if he could still hurt people.

“I can,” Raymond said. “I need to work on not hating myself, and when I have a situation, think.”

BACK IN HER OFFICE, Soto made her assessment. “Honestly, I didn’t know what to expect,” she said. “But I think he has a good understanding.” On her walls, pictures of kittens in precarious positions were posted next to group photos of past classes. “Going through the role play, Raymond realized how dangerous he is. He scared himself. He saw it. He kept saying he’s scared, he doesn’t want to hurt the kids. To me, that’s the difference between passing and not passing. He wasn’t resistant to recognizing how dangerous he can be.” Within the next month, he would be going before a committee to discuss his overall improvements, and she was optimistic that he’d be praised for his progress. But it was hard to know how long the lessons of Giddings would stay with Raymond. All Soto could be sure of was that for now, he was headed in the right direction. Someday, she hoped, in five or ten years, he’d remember her on his release anniversary and call.