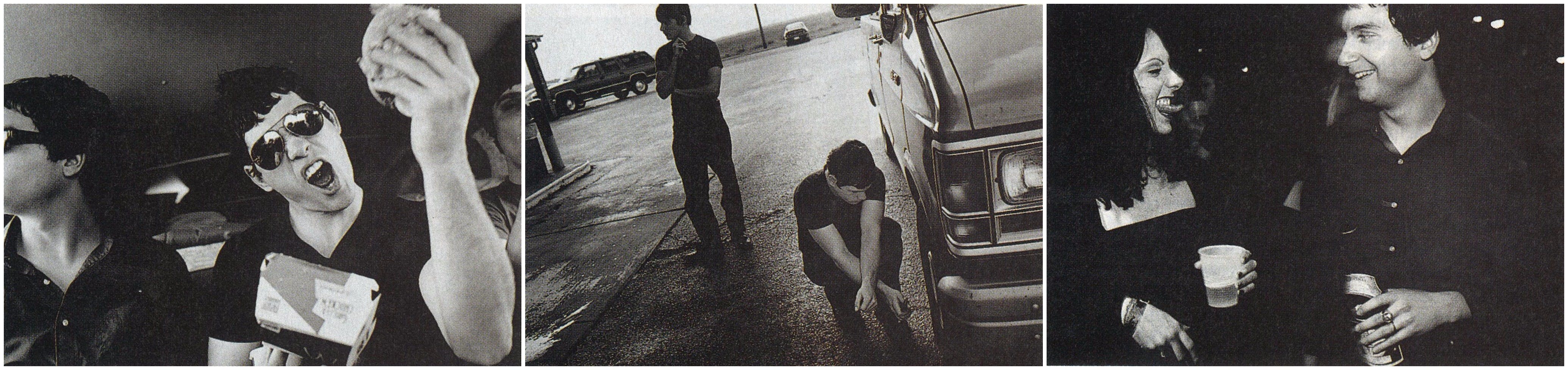

The van’s engine reeked of burning oil when the Trail of Dead stopped outside Winnie on the warm spring afternoon this year that inaugurated the band’s first world tour—a journey that would eventually take the Austin foursome as far as Oslo, Norway, but which seemed in danger, at that very moment, of ending in the switchgrass of East Texas. The group was already running late for its first show in New Orleans, so after a few perfunctory glances under the hood and against better judgment, Neil Busch, Conrad Keely, Jason Reece, and Kevin Allen piled back into the van and hit the road. But about an hour later, as darkness was settling over Southern Louisiana, the engine gave out at a run-down gas station along the poorest fringes of Lake Charles. The prospects were grim: The only passersby were a homeless man selling stolen watches and a gold-toothed thug in a lowrider Cadillac who stared at the four musicians, all wearing jet-black mod haircuts and thrift-store clothes, as if he had spotted an extraterrestrial life form. Jason leaned against the van and surveyed the dismal scene. “This,” he said with a sardonic grin, “is the rock and roll lifestyle.”

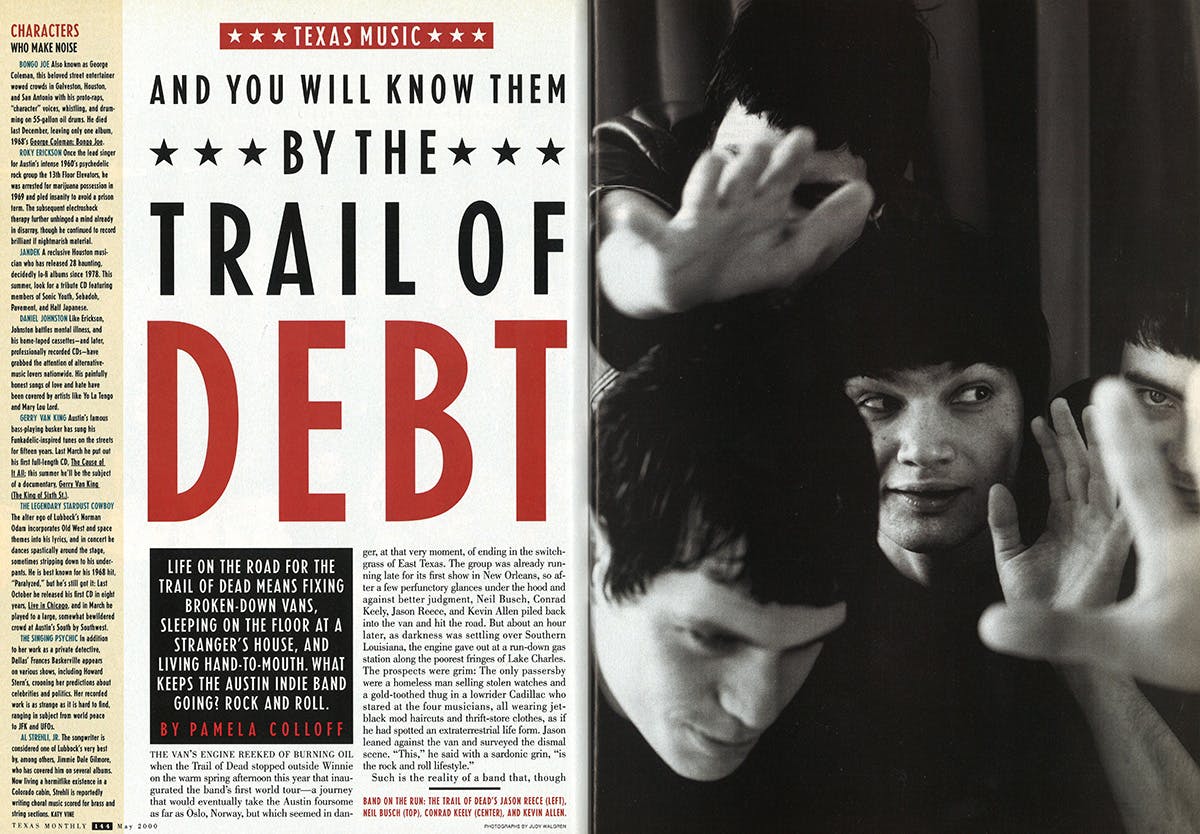

Such is the reality of a band that, though hugely popular in both the Texas underground music scene and abroad, will most likely never meet with commercial success. The Trail of Dead—whose unwieldy full name is . . . And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead—instead has a more obscure appeal, its music largely relegated to the world of college radio stations and punk rock clubs and purveyors of vinyl. The lack of mainstream recognition is not for lack of talent, though, since few other struggling Texas bands have received such critical acclaim: The Trail of Dead has already been dubbed the “mutant progeny” of such Texas music mavericks as Roky Erickson and the Butthole Surfers, and Spin and Rolling Stone have written rave, albeit brief, reviews. The group’s second album, Madonna, was named one of the best records of 1999 by England’s premier music magazine, New Musical Express. “We hear from fans in places like Greece, Turkey, Russia, Germany, and Norway,” said Conrad. “We get lots of enthusiastic e-mails from them saying things like ‘You make big youth noise.’” Several of the band’s smashed guitars have even appeared on the online auction house eBay.

But because the Trail of Dead does not write the sort of catchy pop songs that get mainstream radio play, it lacks the backing of a major record company. Instead, the band is signed to a small independent label, Merge, and must finance nearly every aspect of its work—from recording to going on tour—with borrowed money from the label, slim profits from shows, and whatever spare change day jobs might provide. “We should really be called ‘ . . . And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Debt,’” Conrad quipped in March. “We barely have enough money to get to England.” This, in spite of the fact that the band was scheduled to play a festival in Sussex, En-gland, in only two weeks in front of a crowd of thousands, opening for perhaps the most revered band in the indie rock world, Sonic Youth. Merge would provide their plane tickets out of New York, Conrad explained, and the band would make the rest of the cash it needed playing shows as it drove up the East Coast. But at that moment, the band members were still stranded in Lake Charles—with only a list of friends’ phone numbers, less than a hundred dollars to their name, and a broken-down van that wouldn’t budge.

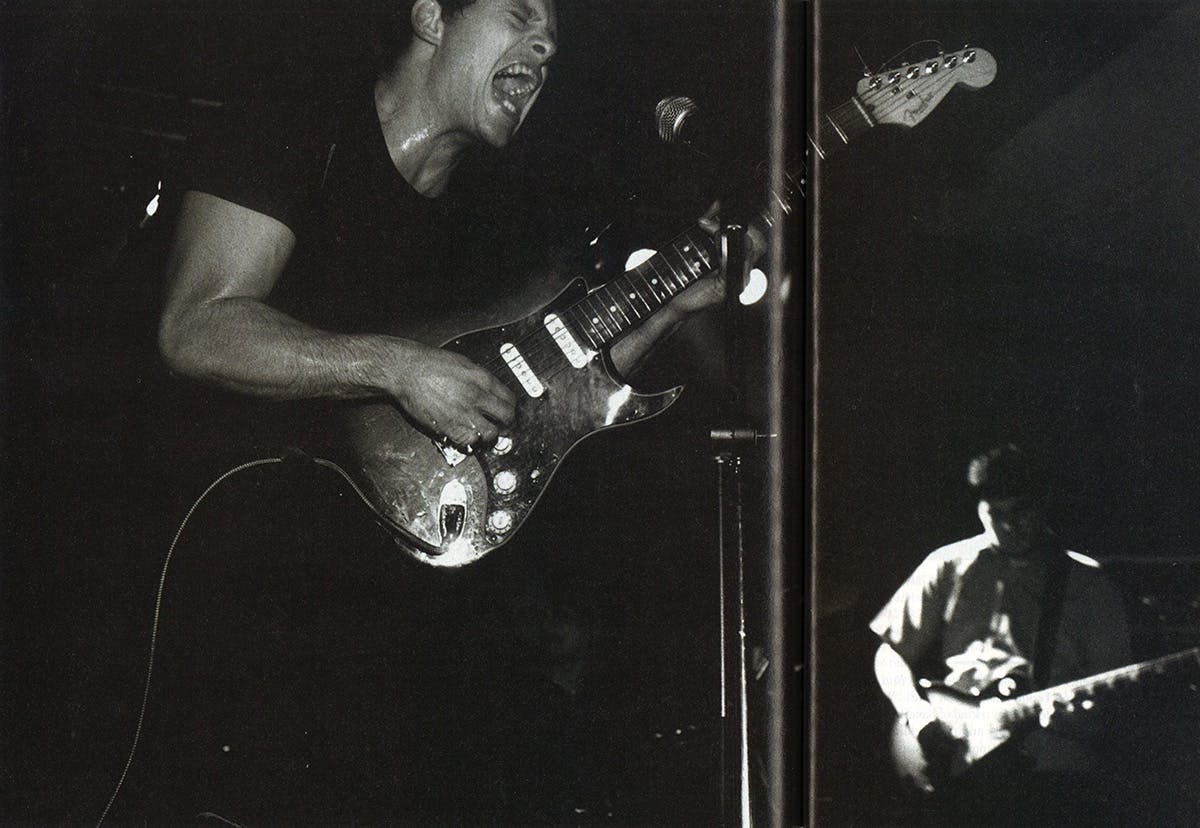

I decided to spend a few days on tour with the Trail of Dead after seeing its knockout performance at this year’s South by Southwest Music Festival in Austin—the only band, out of 987, whose show ended with a train wreck. The group is known for its spectacularly chaotic, crash-and-burn theatrics, which have earned comparisons to the Who and the Stooges and even inspired one critic to recall Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. The South by Southwest show was similarly enthralling, ending in a squall of feedback and distorted guitars, the stage strewn with beer bottles and fallen mike stands and broken drumsticks, the scene so riotous that the club’s management eventually cut first the sound and then the lights. As if on cue, as the crowd fumbled around in the dark, a train passing behind the club frantically sounded its horn—someone had abandoned a pickup on the tracks—and then applied its brakes. It was too late: There was a prolonged, hideous sound of metal impacting metal. “Man, they really know how to put on a show,” the guy standing behind me marveled.

Less than a week later, the Trail of Dead, along with me and photographer Judy Walgren, squeezed into a battered 1994 Dodge Ram and hit the road. It was a tight fit since the band members had packed the van with everything they might possibly need for a seven-week tour, a stockpile that included a can of air freshener, an issue of Penthouse, a bottle of sake, a shrine to the rap group Public Enemy, copies of Paradise Lost and Siddhartha, a sketchbook, a toolbox, one Texas flag, two pea coats, four sleeping bags, four suitcases, eight guitars, two amplifiers, a bass cabinet, a drum set, an effects rack, a spare tire, and an I Love Jesus tag that hung from the rearview mirror. (“To ward off the cops,” Conrad explained.) He and Neil slouched in the back seat, while Jason reclined above them in a makeshift loft. Kevin, the most fresh-faced of the four musicians, who are all in their mid-twenties, took the wheel.

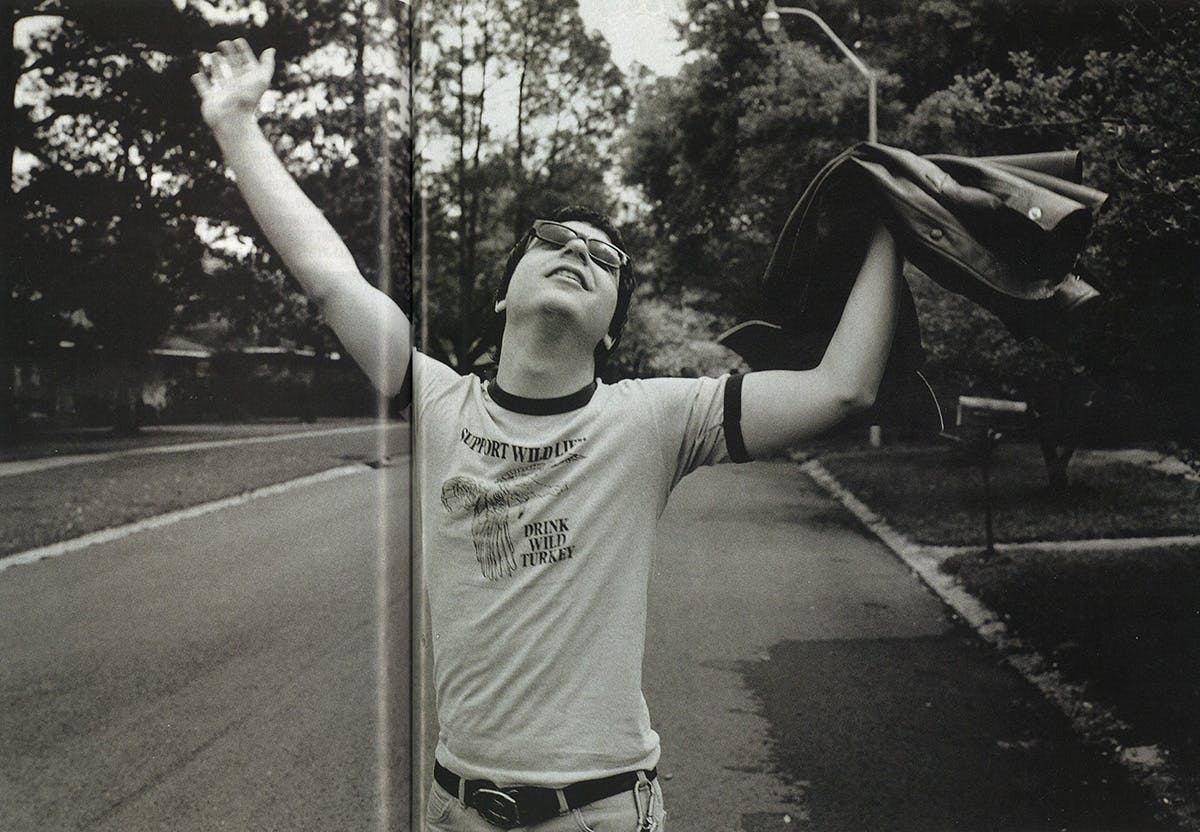

Though the group was formed just five years ago, this trip marked the Trail of Dead’s seventh tour. Conrad and Jason, childhood friends who grew up together in Hawaii, moved to Austin in 1995 to start a band. They settled on the name “. . . And They Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead” because it seemed fittingly epic. “It sounded like a spaghetti western, like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, and we’re big Sergio Leone fans,” Jason said. “We used to spell out the name in saloon letters, for a kind of bandito look.” The band’s early music was unpredictable and maniacally fast, often lacking any discernible melody, with Conrad and Jason each flailing their instruments and their limbs around in hopes of provoking a response from the audience—a “theater of spectacle,” as Jason remembered it. “We had a crappy guitar, a crappy amp, a mismatched drum kit. Whoever was drumming sat on a milk crate.” The duo was later joined by Kevin Allen, a guitarist from College Station, and bassist Neil Busch, who hailed from Houston.

To make a name for themselves in the saturated Austin music scene, the Trail of Dead put on shows that were notoriously rowdy: Cheap guitars were routinely smashed to pieces, stages were left ravaged and sometimes destroyed. “People often mistake our enthusiasm for aggression,” Conrad said with a smile. The group was banned, at one time or another, from every punk rock club in Austin—no small feat in a town accustomed to musical extravagances—and wore its exiled status as a badge of honor. The band was equally unruly on the road: In Minneapolis it was kicked out of a club for lighting fireworks during a show, and in Columbus, Ohio, the group was paid $100 to leave a club after brawling onstage. In San Antonio, after repeatedly violating a sound ordinance, the band was escorted to the city limits by the police. “The cops said, ‘You boys get out of town and don’t come back,’” Neil proudly recalled. “It was like when Ozzy pissed on the Alamo.”

Underneath the frenetic misbehavior, however, was a band that was producing some surprisingly good music. King Coffey, the drummer for the Butthole Surfers, signed the group to his Austin-based label Trance Syndicate Records in 1997 and put out its self-titled album the following year. That effort turned heads: David Fricke praised the Trail of Dead’s “glorious display of shattered-glass guitar tonalities and migraine-beat precision” in Rolling Stone in 1998, and Detour magazine invited the band to New York for a photo shoot. All was going well until that fall, when the Trail of Dead tried to launch a tour that was supposed to take it to 29 cities around the country. The band had met with disaster on the road before, arriving at an El Paso show pulled by a tow truck, losing several guitars in a New York City heist, and putting out a fire that started in its old Ford Econoline outside Waco. But all of that paled in comparison to the calamity that struck, only one day into the band’s first major tour, in 1998, when its van was stolen in New Orleans.

“It had everything in it that we had collected since we were teenagers,” said Neil with a sigh. “A customized Les Paul, a Flying V, a bass cabinet that had gone on tour with AC/DC . . .”

“We were completely devastated,” Kevin said.

Everyone nodded and then muttered in unison, “Devastated.”

The band members scrapped the tour, though not before they borrowed guitars and a girlfriend’s car, drove 36 hours straight to New York, and played the College Music Journal festival several days later. Trance Syndicate folded soon afterward, and the group—faced with breaking up or persevering—decided to stick it out and headed back to the studio. A tape of its rough mixes caused indie rock stars Superchunk to take notice, and the band, which owns Merge Records, asked the Trail of Dead to join its roster last year. Still, as the relationship with Trance Syndicate demonstrated, a record deal doesn’t solve all of a band’s problems. “People have this misconception that things are easy because we’re signed to a label,” Jason said. “We’re doing well for a punk rock band: We go out on the road, we tour, we play. This is the dream, but we’re still at the very bottom of the deal.”

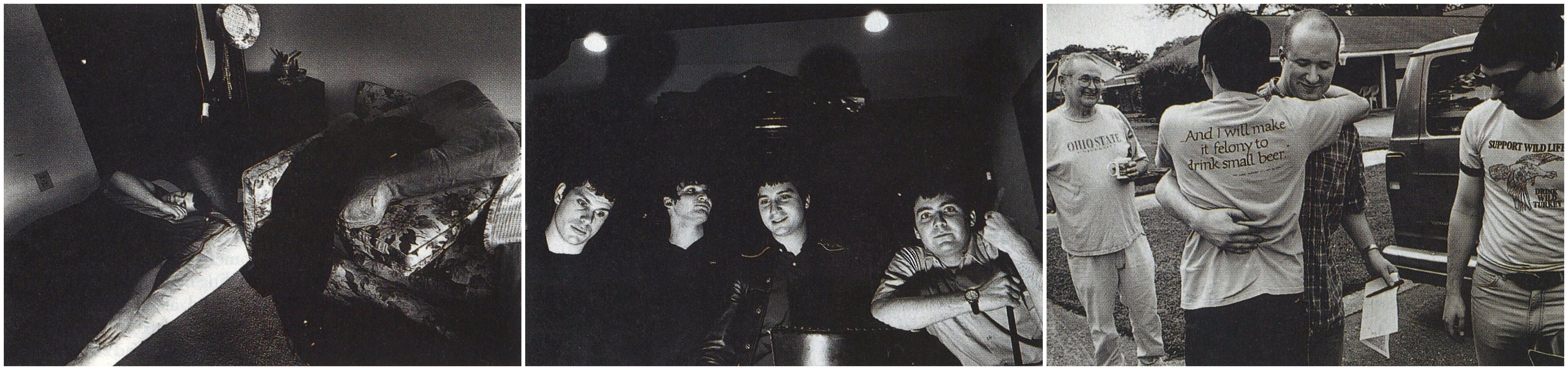

“This is not a luxurious life,” added Neil. “You can’t work a decent job, your girlfriends are angry, your friendships fall apart. You’re stuck in a van with three sweaty guys all the time. But we’re best friends; we’re like brothers. We’ve all lost jobs and broken up relationships for this band, and we’re in it for the long haul.”

The long haul found us five hours outside Austin with a van that refused to start. Neil tinkered with the engine until dusk, finally getting it to run long enough for Kevin to steer us to an auto parts store, where the two set to work. Touring is as much about waiting around—for a sound check to end, for a club owner to pay up—as it is about the few cathartic moments onstage, and the band seemed resigned to being stuck in Lake Charles for quite a while. Conrad sat on the curb sipping sake and watching Neil check the spark plugs, every once in a while dryly singing a few lines of Bruce Springsteen: “You can’t start a fire / You can’t start a fire without a spark . . .” The group has become proficient in fixing such problems—once, in New Mexico, they looped guitar strings around a wobbly muffler to anchor it to the van—and by eight o’clock, the engine was running again. “Let’s haul ass!” Kevin cried as he fired it up, and we all took our places back in the van, now strewn with fast-food wrappers and empty Lone Star cans. We drove hurriedly past towns called Evangeline and Iota and Mire, over the Atchafalaya River and the Mississippi, until we reached New Orleans, only a few minutes before they were scheduled to play.

The club was dark and only half full, and the band put on a lackluster show having missed the sound check. The headliners, a local metal act called Blackula, had already filled the stage with its equipment, and the Trail of Dead were left with little room to play, perching themselves awkwardly on the edge of the stage. But their loyal fans, mostly girls, didn’t seem to care: They clustered around them, riveted, and swayed to the sound of Jason’s voice. At the end of the show, a pretty girl who had seen the band play in Tampa Bay last fall and who now stars on MTV’s The Real World: New Orleans, approached Kevin, her camera crew in tow. “I love your band,” she gushed.

That night, like most nights on the road, Neil, Conrad, Jason, and Kevin relied upon the kindness of strangers, staying with a drummer named Natalia they had met the last time they passed through New Orleans. They rarely stay at hotels—even a single room at the Motel 6 is deemed lavish—since every penny spent further distances them from making a profit. They will not earn royalties until they have settled the overhead costs of touring, recording, and merchandising with Merge. “The label is like a bank you borrow from,” Jason explained. “They give you name recognition and publicity and distribution for your records, but everything else you have to pay back.” Since Madonna’s release in October, fewer than 10,000 copies have sold, of which the band receives only 30 percent of the profits; its shows, which usually command $250 guarantees, are hardly money-makers once the cost of gas, food, van repairs, equipment, and the booking agent’s 15 percent cut are factored in. Unless the band gains a wider audience, the chances of its members quitting their day jobs—serving coffee and working as temps—aren’t good. The best they can hope for, Jason explained, is to become self-sustaining while on the road. And long term? “To have a number one hit single,” he laughed.

Natalia threw a party for the band that night that ended near dawn, when everyone collapsed onto her floor and tried to catch a few hours’ sleep. Conrad and Jason wedged themselves between the furniture in Natalia’s tiny living room, Neil crashed in the van, and Judy and I lay down in the kitchen. Around noon, everyone awoke bleary-eyed among the remains of the festivities—spoiled sushi, empty beer cans, overflowing ashtrays—and joked about the night before; Conrad strummed his guitar as afternoon sunlight crept through the blinds. Kevin had caught a ride to Baton Rouge the night before, and after bidding Natalia good-bye, we headed his way, the van’s radio humming. The conversation soon turned to the number of Austin groups that had fallen by the wayside in recent years, never able to translate hometown popularity into a broader appeal. As if to prove us wrong, the hit song “The Way,” by the Austin band Fastball, came on the radio, then another, by Sixpence None the Richer, from nearby New Braunfels. “It’s Austin hoot night in Baton Rouge,” Conrad joked of the unlikely song pairing. “Someday we’ll be rock stars too,” Jason said with a grin.

It takes a certain audacity to slog it out in a largely unknown punk rock band, but shows like the one the Trail of Dead played that night in Baton Rouge perhaps make it all worthwhile. The venue, a bar called Spanish Moon that had been a black social club during segregation, was packed when the Trail of Dead took the stage that Saturday night. The band was in fine form, exploding with energy as it tore through its songs, the crowd dancing and reeling and waving its fists. As the show wound to a close, Neil, bass in hand, fell to his knees; Jason launched into a Pete Townsend windmill routine and then tumbled into the crowd. Conrad kicked the drum kit across the stage, toppling a stack of amps, and Kevin tried to coax a melody out of his now mostly broken guitar strings. The band was sweaty and ebullient, the audience transported. They pulled first Jason and then Neil into the crowd and held them aloft—Jason still singing, Neil strumming the bass—while feedback reverberated against the club’s brick walls.

As the set came to an end, Jason regained his footing onstage and stared out into the crowd, grinning in the spotlight. In seven weeks he would be back in Austin serving coffee, but for now, this was his moment. “There’s not much left to play with,” he shouted to the crowd, motioning toward the fallen amps and disassembled drum kit. “I guess we should just pack up and head home . . .” But the audience screamed for more, and the band gave it to them, launching into a blistering encore. The stage was slick with spilled beer and broken glass, the crowd both drunk and exultant. “Rock and roll!” the girl next to me screamed. “Rock and roll!”

Essential Listening

Madonna (Merge)