This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Most weekday mornings, a security guard comes to the front door of a one-story North Dallas home, where an elderly woman waits to be taken to work. With her perfectly curled blond wig and her cottony white skin, 77-year-old Mary Kay Ash is one of the most recognizable women in the United States. Her name, according to a market study, is almost as well known as Coca-Cola. Her most recent motivational book, Mary Kay—You Can Have It All, made every major best-seller list within days of its publication in August. Mary Kay is treated with such adoration by the 400,000 women who sell her cosmetics—and the millions who buy them—that she has eleven secretaries to help her handle the daily flood of gifts and fan mail. But America’s grande dame of cosmetics is not satisfied. She takes the arm of the security guard and steps carefully into her pink Cadillac for the twenty-minute drive to her office. “When you have someone lapping at your heels all the time, you kind of speed up,” she says.

Only five miles from Mary Kay’s home, another woman struts out the door of one of the most lavish homes in Dallas, a $12 million, 18,000-square-foot mansion built to resemble a seventeenth-century French château. Wearing a short designer skirt that shows off her cocktail party legs, her skin so soft it looks airbrushed, 42-year-old Jinger Heath hops behind the wheel of her four-door white Mercedes and races to her company, BeautiControl, a cosmetics firm modeled almost exactly on Mary Kay Cosmetics. “We like to move fast around here, really fast,” Jinger, her glamour-puss face topped by swirls of blond hair. “When you’re the smaller company and you have the huge pink cloud hanging over you, you have to move fast.”

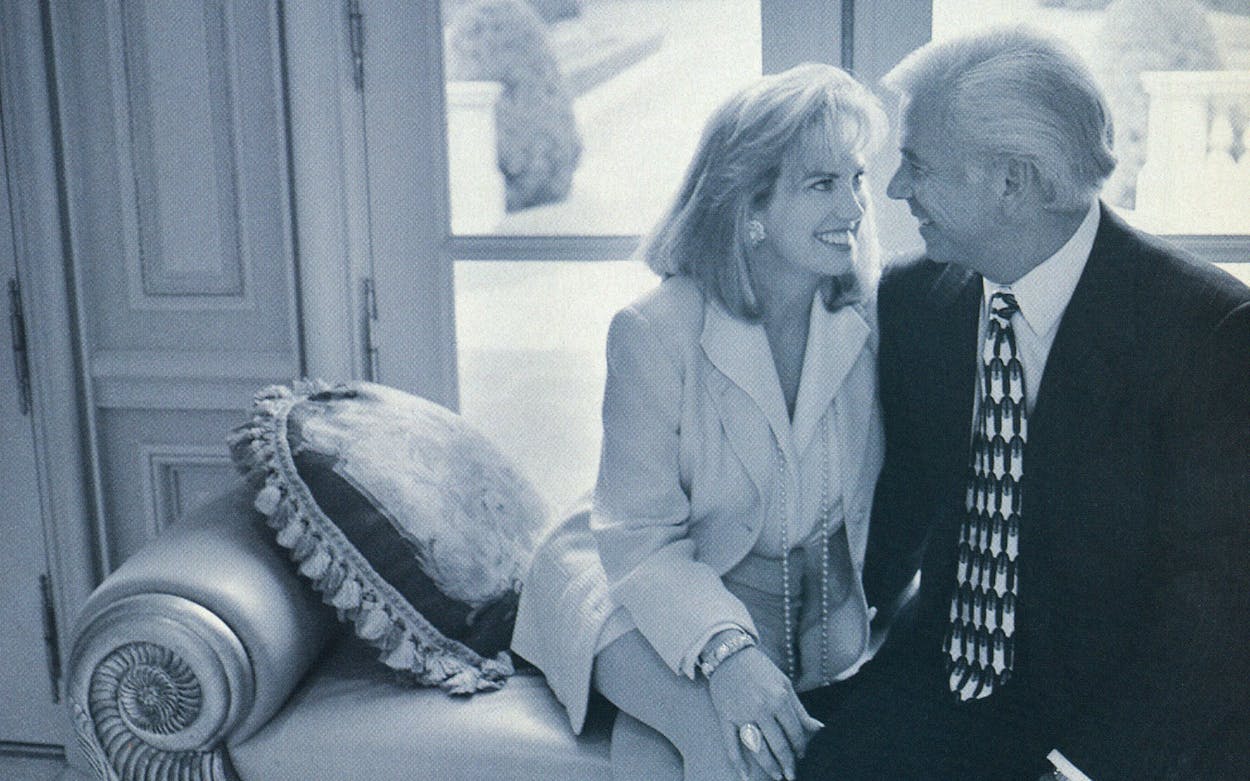

It is one of the most colorful battles in American business, waged between two wealthy Dallas cosmetics queens from two vastly different generations. Compared with Mary Kay’s mammoth company, which sells $866 million (in wholesale dollars) worth of cosmetics to 20 million women a year, BeautiControl is, as Mary Kay herself puts it, “a gnat”—less than a tenth of Mary Kay’s size. But in the past twelve years, under the leadership of Jinger, who is the chairman of the company, and her silver-haired husband, Dick, who is the president and chief executive officer, BeautiControl has grown dramatically, from $1,870,000 in sales in 1983 to an estimated $80 million this year. And now BeautiControl is preparing for an all-out assault on the Mary Kay empire. On the inevitable day when Mary Kay Ash finally steps down from the company she created, Jinger will have her best opportunity to capture the hearts, and faces, of a new generation of American women.

While traditional cosmetics companies such as Lancôme and Estée Lauder promote their products through multimillion-dollar advertising campaigns built around a supermodel or a photograph of a jar of facial cream, Mary Kay Cosmetics and BeautiControl are direct-sales companies, which bypass advertising altogether. Instead of selling their cosmetics in department stores, the two companies sell them directly to their saleswomen, known as “consultants,” who operate as independent contractors. The consultants then sell the cosmetics to consumers at twice what they paid for them. A largely misunderstood and often lampooned enterprise—”A lot of magazine beauty editors think of us as nothing but crazed doorbell-ringing women,” says Jinger—direct-sales cosmetics companies account for nearly 20 percent of this country. For the past thirty years Mary Kay has built her kingdom with a mesmerizing sales pitch that offers supremely normal, middle-class women the chance to make more money and win more prizes (including the world-famous pink Cadillac) than they ever dreamed—in other words, to become just like Mary Kay. The incorrigibly convivial Jinger Heath pushes a similar dream, only she rewards her top salespeople with a Mercedes or a Cadillac of any color they choose.

Although the feud between BeautiControl and Mary Kay Cosmetics goes back thirty years, to when the two companies were just getting started in Dallas, Jinger Heath gives the conflict the dimensions of a modern-day fairy tale. Depending on whose side you’re on, either Jinger is the fair-skinned Snow White, viciously hounded by an aging, jealous queen, or in a convoluted version of the Cinderella story, Jinger is the evil stepdaughter trying to sneak her foot into Mary Kay’s slipper. For her part, Mary Kay cannot restrain herself when it comes to her ultrafashionable young rival. “Anyone who gets fired at our company takes a taxi over there,” Mary Kay tells me. “She [Jinger] gets all she can get from them, wrings them out, and fires them.” The empress peers at me, her blue eyes sitting in her perfectly powdered face like two cold lakes. “She’s the Leona Helmsley of the cosmetics business.”

“I know some people are going to think about me, ‘That witch, who does she think she is, trying to beat up on a sweet little old lady,'” Jinger says, snacking one afternoon in her office on a non-fat brownie and using a straw to drink from her glass of water (to avoid ruining her lipstick). “I think Mary Kay is very kind and she is very genuine. But I definitely have some resentment toward her company because I think every new product of ours is copied by Mary Kay Cosmetics six months later. And then they tell the world that we are copying them.”

Although it seems almost impossible that BeautiControl, with its 42,000 consultants, could ever overtake Mary Kay Cosmetics, this is an industry in which the right image literally can determine who succeeds and who fails. “Mary Kay might scoff at the idea of someone toppling her,” says Gary Jones, BeautiControl’s director of product development. “But soon, every town in this country is going to have a woman who works for Mary Kay and another one who works for Jinger. It’s going to be a catfight among the women in the field like you’ve never before seen.”

By far, the nation’s largest direct-sales beauty products company is Avon Products, which has $4.3 billion in annual sales. Mary Kay Cosmetics is the second biggest, with BeautiControl a distant third. But the famed “Avon calling” ladies, who focus on lower- and middle-income consumers, do most of their business by dropping off a catalog at someone’s home. Mary Kay and Jinger, however, try to lure America’s more affluent consumers by sending their armies of consultants to neighborhoods and office buildings across the nation, offering everything from free facials and skin-care classes to “image update workshops” in the hope that the women will buy their cosmetics. To keep the consultants motivated, they have to be almost superhumanly inspired. And as Mary Kay Ash has taught corporate America, the best way to inspire salespeople is not simply to give them fat commission checks. It’s to make them feel like they are celebrities.

Every summer Wall Street analysts, chief executive officers of other companies, and even professors from the Harvard Business School come to Dallas to watch one of the most amazing business conventions in the world. Known as Seminar, it’s the annual gathering of nearly 40,000 of Mary Kay’s consultants at the Dallas Convention Center, all of whom pay a $125 registration fee and their own travel expenses for the chance to spend three days cheering their founder and the top salespeople in the company. During Awards Night, Mary Kay, wearing a long sparkly gown, presides over her conception of the promised feminine land, a world that is part sorority and part The Price Is Right. “Are you ready for the most exciting moment of your life?” she asks, holding out her hands exactly the way the pope does when he blesses his flock—and the roar is deafening. Each year at Seminar, the company gives away $6 million in prizes to its top salespeople, from mink coats to diamond rings. On a stage lit up like a Las Vegas floor show, the top-selling women walk down a curving set of stairs, escorted by fawning males (jokingly called “the token men” by Seminar attendees) who work at the Mary Kay headquarters. As cymbals clash and timpani drums roll, Mary Kay turns her salespeople into princesses, putting crowns on their heads and seating them on a throne onstage.

To an outsider, the ceremony might look ostentatious, but Mary Kay is a genius at tapping into these women’s emotions. At Mary Kay Cosmetics women have found a world of their own, a cloister almost entirely devoid of the other sex. (The husbands who come to Seminar are shuttled off to “husbands’ seminars” to learn how to support their wives and accept the reality that their wives make more money than they do.) Mary Kay has her top saleswomen give personal testimonies in which they describe how they were once lost, drifting through life as underpaid schoolteachers or secretaries, making little money, feeling underappreciated by their husbands and children. Then, through the act of selling Mary Kay cosmetics—and recruiting other women to do the same—they found true liberation and were able to buy dream houses and put their kids through college.

Mary Kay loves to paint a somber portrait of the women who work in corporate America, which she calls “the other world.” They lead tired lives, slaves to their nine-to-five jobs, unable to crack the glass ceiling. In the other world, says Mary Kay, women make only 76 cents for every dollar men make. They also lose their femininity in their climb up the corporate ladder, changing the way they dress and talk to fit in with men. With Mary Kay Cosmetics, however, a woman can be a milk-and-cookie mom and have a career too, able to set her own work hours so she can take her children to school, be there when they get home, and be there for her husband.

To become a consultant at Mary Kay Cosmetics, a woman spends $100 for a day of training and a beauty case filled with cosmetics. She tries not only to get women to buy cosmetics but also to persuade them to sell Mary Kay’s cosmetics. It’s in the recruitment that the real money can be made. If a consultant signs up another salesperson, the consultant makes a commission from the company on everything her recruit sells. If the recruit recruits a saleswoman, the original consultant makes a smaller commission on everything that saleswoman sells. If a consultant brings in thirty recruits and they total $16,000 in sales over a four-month period, the consultant becomes a “director.” (The company’s seven thousand directors make anywhere from $35,000 to $60,000 a year.) If a consultant’s sales and recruiting continue to increase, she can receive a pink Cadillac, the trademark of the Mary Kay lifestyle, and if she reaches the top of the pyramid, she attains the prized possession of national sales director. Last year Mary Kay’s 97 national sales directors earned an average salary of $279,000 a year—which is why Mary Kay claims to have produced more wealthy women than any other company in the world.

It is difficult to overstate how Mary Kay is revered among her consultants. At Seminar, when the organist launches into Mary Kay’s theme song, “I’ve Got the Mary Kay Enthusiasm Down in My Heart,” many of the women dissolve into tears. When Mary Kay steps onto the stage, consultants rush forward with their cameras to get her picture. A consultant once came to the stage and presented her with a painting that showed Mary Kay and Christ standing together, with Christ looking at Mary Kay approvingly. At this past summer’s Seminar, a young woman stood before a teary-eyed audience telling the story of her husband, who had cancer and had been given six months to live. But Mary Kay had him flown to Dallas. The man went to see a cancer doctor whose research is funded by Mary Kay. Within weeks, her husband had gone into remission. “Without you, Mary Kay, my husband would not be here with me,” the woman said. She then added that while waiting for him to recover in the hospital, she had spread out an array of Mary Kay cosmetics on his bed and sold them to the nurses.

In most respects, BeautiControl’s annual Celebration is identical to Mary Kay’s Seminar, with consultants marching across the stage and receiving awards and the directors delivering their feminized Horatio Alger stories. (BeautiControl’s salespeople earn money under the same type of pyramid structure used at Mary Kay.) Held in a football field–size ballroom in Nashville’s Opryland Hotel (60 percent of BeautiControl’s sales force is within five hundred miles of Nashville), Celebration is much smaller than Seminar, with only four thousand women attending. But there is one major difference. As rap music blares, Jinger Heath comes scissoring across the stage in a tight outfit that is as colorful as a Rose Bowl float. Her mostly younger consultants kick off their shoes, stand on their chairs, and let out a high-pitched scream that sounds like a circular saw cutting into a log. They stare at Jinger the way little girls stare at their Barbies. When she grabs the hand of her husband, Dick Heath, the kind of good-looking guy one normally sees posing in a tuxedo ad, the women give a lusty, feminine rebel yell, “Woo-oo-oo-oo.”

Mary Kay is sometimes called “the grandmotherly version of Dolly Parton,” and she lectures her flock on the importance of the Golden Rule and other weighty matters; Jinger likes it to be known that she is a marathon runner and a kickboxer and tells her troops that she marks her menstrual cycle on her daytimer so she’ll be prepared for her “naturally down days.” Each year at Seminar, accompanied by the ubiquitous organ music, Mary Kay gently reads the lyrics to a sentimental song (“I believe for every drop of rain that falls, a flower grows”). At Celebration, Jinger gives a fast-paced speech that sounds like a compilation from popular self-help books. She talks about the power of the unconscious, the need for creative visualization, and the importance of programming negative thoughts out of your brain. “Repeat after me,” she tells her consultants. “I believe in me!” The consultants roar back, “I believe in me!” Jinger always tries to give her consultants a little jolt. At this past summer’s Celebration, she stepped out in black Anne Klein knee-high boots, black Chanel shorts, and a black Ralph Lauren tuxedo jacket to present her annual “fashion forecast.” Her consultants applauded vigorously, their bracelets clanging, scents of a hundred perfumes rising into the air. Then they dropped their heads and took notes as Jinger told them that leopard-spotted clothes and bomber jackets were back and that Hollywood sunglasses were “way cool!” “But ladies,” Jinger cautioned, “the perfect coif is out. Don’t make yourself look like you’ve spent too much time in the beauty salon—and remember, no helmet hair!” Jimmy Sue Coburn, who had been a director for Mary Kay Cosmetics in the sixties before switching to BeautiControl in the eighties, says, “I admit, there’s no one who can float across a stage like Mary Kay. But Jinger is the new woman—gorgeous, high fashion, the type who acts like one of the girls.”

Jinger’s persona, however, makes Mary Kay people seethe. In various conversations with Mary Kay executives, I heard Jinger described as a “society bimbo” and a “copycat.” “Her company is a rip-off of everything we’ve done,” one executive told me. They are furious when they hear Jinger trying to position BeautiControl as the company for young professional women. “Mary Kay’s message appeals more than ever to the younger generation looking for a great business opportunity,” says Curran Dandurand, Mary Kay’s executive vice president of global marketing, who adds that half of the Mary Kay consultants are under 35. Jinger replies, “When Wall Street analysts come down to look at our convention and then Mary Kay’s convention, I think it’s fair to say they’re overwhelmed by our women. Women who come to BeautiControl are looking for more out of life than rah-rah songs and a pink Cadillac.”

Not surprisingly, there are constant rumors of corporate spying and double-agent consultants. Female staffers at BeautiControl’s headquarters supposedly work as Mary Kay consultants, and vice versa. BeautiControl officials, who keep paper shredders in their offices, are convinced that Mary Kay has spies at BeautiControl headquarters. “I know for a fact if I come out with a new product today,” says Clifton Sanders, the senior vice president of BeautiControl’s research and development, “the first ones to see it will be Dick and Jinger Heath, and the second ones will be the people across town at Mary Kay.” Dandurand snorts at the accusation. BeautiControl, she says, “is a non-issue. Our competition does not come from BeautiControl, it comes from companies like Estée Lauder.”

Observers of this curious rivalry—and there are plenty of them in Dallas—all agree that if the two women ever sat down and talked to each other, they would realize how much they have in common. Both are great storytellers. Both are born-again Christians who sprinkle references to God throughout their conversations. Both like to poke fun at men’s sense of superiority. Perhaps in another context, Mary Kay, who lost her own daughter to pneumonia in 1991, would look upon Jinger as a surrogate daughter.

Despite her tenderhearted image and her fame for aphorisms—her well-known assertion, for example, that the “P&L” in her company budget means not “profit and loss” but “people and love”—Mary Kay is a proud woman who has devoted her adult life to building her company. She is clearly appalled that a woman nearly half her age—one who never had to make the sacrifices that she did—could zero in on her empire. “If you want to understand why Mary Kay is one of the most successful business figures in this country,” says Anna Kendall, her secretary in the early sixties, “then you have to understand her obsession with work. She has the ability to stay focused, no matter what comes her way.”

Born in Houston on May 12, 1918, Mary Kay was taking care of herself before she entered elementary school. Her father, an invalid afflicted with tuberculosis, spent most of Mary Kay’s early childhood in a sanatorium. To pay the family’s bills, her mother managed a restaurant, leaving the house at five in the morning and returning home after nine at night. At the age of seven, little Mary Kay was taking a streetcar to downtown Houston, where she bought her own clothes with money her mother had given her. If she had any spare change, she would treat herself to a pimento-cheese sandwich at the Kress department store.

When Mary Kay tells this story in public, she makes it sound so charming that her audiences burst into laughter; but the truth is that Mary Kay grew up practically an orphan. At the age of seventeen she married a handsome young man who played in a Houston band called the Hawaiian Strummers. They had three children. In her autobiography, Mary Kay writes only that the marriage broke up after he husband was drafted into the Army. During one of our interviews, she added an extra detail. “I found out that he had been living with this other woman for three years while he was gone,” she said, her diamond rings clinking lightly together as she folded her hands.

Suddenly, Mary Kay was a young single mother at a time—the late thirties—when a divorcée was expected to find another husband. Instead, she moved to Dallas to work for a direct-sales company called Stanley Home Products, selling household products at “parties” hosted by a housewife and attended by neighborhood women. She was, by all accounts, an absolutely amazing saleswoman. She would wrap a red bow around a broom and tell a roomful of ladies, “This would be a great gift for your mother-in-law.” The women would line up to buy her products.

Today, as part of her pitch to inspire her consultants, Mary Kay talks about how she set up Stanley Home Products parties three times a day, lugging a heavy suitcase from one house to another. The story she does not often tell is the one about her neighbors in Dallas thinking she was a neglectful mother. Just before leaving for her evening Stanley party, Mary Kay always made sure to tuck her youngest son, Richard, into bed. But after she left, he often climbed out a window and down a tree and sat on the curb under a streetlight. “Hey, boy, what are you doing out here?” the neighbors would ask. Richard would reply, “I’m waiting for my mother to come home from a party.”

Mary Kay was too good a saleswoman to quit. In her second year at Stanley Home Products, she was named “queen” of sales at the company’s convention. Eleven years later she was hired as the national sales director for World Gifts, another direct-sales company in Dallas. She was an oddity: a single woman making her way in a world full of rough-and-tumble Willie Lomans. She was on the road three weeks a month, recruiting salesmen during the day, training them at night, collapsing into her hotel-room bed after midnight. Unable to look after her son Richard (her two other children were already grown), she enrolled him in a military boarding school.

When I asked her if she ever got lonely during those days, she said with a slight shrug, “I didn’t have time to be lonely.”

“Well, spending all that time on the road, how did men treat you?”

Mary Kay paused, and her eyes moved toward her lap. “They said, ‘You’re too busy for me.’ That’s how men treated me.” For a moment, I thought she might lose her composure. But she took a small breath and looked up at me, her imperial stare back in place.

Despite the romantic gloss Mary Kay likes to put on her history, her life had more than its share of losses. Relationships came and went. She went through a couple of more brief marriages. But according to Mary Kay, the most traumatic blow of that era involved her work. In early 1963, after she asked her male boss at World Gifts for money to develop an audio-visual training program, he decided to hire a young man to be her assistant. Mary Kay taught her assistant the principles of selling and how to train others. Less than a year later, he was promoted above Mary Kay at twice her salary. Devastated, she quit.

When I was following Mary Kay around one day last summer, I heard her tell this story three times—once to a television interviewer, once in an afternoon speech to an audience of her salespeople at Seminar, and finally to me as we were sitting in a small room just off the Dallas Convention Center stage during Awards Night. In the distance came a massive roar from thousands of women as another top sales consultant was introduced on the stage. Mary Kay leaned closer so that I could hear her, and for the first time I heard the anger that still burned from that thirty-year-old betrayal. “Those men didn’t believe a woman had brain matter at all. I learned back then that as long as men didn’t believe women could do anything, women were never going to have a chance.”

Mary Kay decided to form a new company—this one for women. Few people would recognize the irony: a cosmetics company, appealing to a woman’s frilly femininity, built on the then-revolutionary principle that women could do business just fine without men around. She designed a company where a woman could make as much money as she wanted based upon what she sold, not whether the male boss liked her. Knowing that the last time many women had been applauded was when they walked across the stage at high school graduation, she also created a system in which her consultants received a series of prizes, from ribbons and pins to small black and white television sets.

Several years earlier Mary Kay had met a woman, Ova Heath Spoonemore, who was selling homemade skin-care products out of her home. They were made from formulas that the woman’s father, an Arkansas tanner named J. W. Heath (no relation to Dick or Jinger), had created back in the early thirties. He had noticed, after tanning deer hides all day with his special cream, that his hands looked younger. When he put a modified solution on his face, he soon had the skin tone of a younger man. He called his product BeautiControl. When Mary Kay was ready to start her own company, she sensed that the tanner’s story could be a magical marketing tool. She offered the granddaughter of the tanner (Ova Heath Spoonemore had died) a reported $500 for a copy of some of the formulas, then proclaimed in her promotional literature that Mary Kay Cosmetics owned J. W. Heath’s famed “original BeautiControl formulas.”

Mary Kay put up $5,000 to get the business started in a five-hundred-square-foot Dallas storefront. She depended on only two men: Her twenty-year-old son, Richard, ran the administrative and manufacturing parts of the business, and her eldest son, Ben, ran the warehouse. By the end of 1964 sales had reached $198,000. For her first Seminar, Mary Kay cooked a chicken dinner for two hundred women, who wore long dresses and white gloves.

But two years later, one of her first directors, Jackie Brown, who could barely drive a car before joining Mary Kay, alleged that Mary Kay had gone back on a promise to make her the first national sales director. In retaliation, Brown and Marjie Slaten, another Mary Kay director, made a deal with the Arkansas tanner’s granddaughter to buy into the tiny BeautiControl company. Using what they had learned from Mary Kay, Brown and Slaten reorganized BeautiControl into a larger direct-sales outfit, lured away at least fifteen Mary Kay consultants, and set up in an office just down the freeway from Mary Kay’s headquarters. Wearing her bouffantlike brunette wig—Mary Kay was already wearing her blond wig—Brown bought time on television stations around the country to extol the benefits of BeautiControl, making sure to add that she had the original formulas of the Arkansas tanner.

According to Dalene White, one of Mary Kay’s first recruits, the defection by Brown and Slaten “broke Mary Kay’s heart. She had loved those women and felt totally betrayed. But I’ll never forget her marching down the hallways with her shoes off, determined not to let this new company do us in.” In 1966 Mary Kay Cosmetics sued Brown, Slaten, and others who were a part of BeautiControl, arguing that they were trying to destroy Mary Kay Cosmetics by stealing away her consultants and customers. Brown countersued, saying a vindictive Mary Kay was trying to drive them out of business. For three years allegations flew back and forth in court. Finally, in a settlement reached in 1969, Mary Kay was allowed to say that her formulas came from a tanner, but only BeautiControl could use the actual names and pictures of the Arkansas tanner and his family. As lame as the agreement appeared, the damage was done. Some BeautiControl sales directors and consultants, afraid of being sued by Mary Kay, had dropped out of BeautiControl altogether. “We were then in twenty states and just trying to get off the ground,” says Slaten, “and all of a sudden we had to spend most of our money defending ourselves in court.” A few years later Brown and Slaten sold BeautiControl to a New Jersey direct-sales company called Tri-Chem, which made a few halfhearted attempts to build back the company before letting it languish. “I think it’s fair to say that no one was a match for Mary Kay’s charisma,” says Slaten, who is now a high school counselor in New Mexico. (Jackie Brown is running a small cosmetics company in Tyler that sells nail-care products on the QVC television network.)

In the seventies, under Mary Kay’s guidance and her son Richard’s administrative skills (Ben had left the company to return to Houston), Mary Kay Cosmetics exploded. With 50,000 consultants and directors, the company broke $100 million in annual sales in 1979. On 60 Minutes, Morley Safer introduced Mary Kay to America, calling her “a pink panther . . . whose instinct for doing business and making money is as finely tuned as a jungle cat going for the kill.” Her personal life had settled down. In 1966 she had married a Dallas sales representative named Mel Ash, a kindly man who didn’t mind living in Mary Kay’s shadow. Every Thursday night, he gave Mary Kay a present (usually jewelry) accompanied by flowers and a Hallmark card. Still, Mary Kay was a workaholic: She says she got fidgety spending an evening watching television with Mel. A few days after Mel died of cancer in 1980, Mary Kay flew to St. Louis to speak to 7,500 directors and consultants. She told me that her trip was what Mel would have wanted. “Even though I was grief-stricken,” she said on another occasion about that trip, “I made certain that I generated a positive attitude for everyone present.” But her positive attitude was about to be tested again. That year the news broke that Mary Kay’s old nemesis, BeautiControl, had been purchased by a good-looking couple named Dick and Jinger Heath.

Richard “Dick” Heath grew up in Illinois and began working during high school after his father died of alcoholism. After marrying at age nineteen, he quickly became the father of two sons. In college he sold pots and pans door-to-door to support himself and his family. He moved into an executive position at a Florida-based direct-sales cosmetics company, then went to work for Tri-Chem, where he rose to senior vice president. When he was fired from Tri-Chem after a series of disputes with another senior executive, Dick decided to run a direct-sales company on his own. He made a $60,000 down payment (his life savings), took out a $484,000 ten-year loan, and bought BeautiControl. It seemed like a foolish endeavor to try to build a cosmetics company in Mary Kay’s back yard. With only 650 consultants and eight sales directors, BeautiControl’s sales were a paltry $761,000 a year.

But Dick was convinced that Mary Kay was vulnerable. He wanted to recruit a sales force from the large market of educated younger women entering the work force—a market that Mary Kay at the time was neglecting. Heath wanted women who would feel that BeautiControl was as legitimate a profession as banking. He also knew that the company needed a figurehead, someone who could inspire modern women and keep them with the company.

Dick had met Jinger in 1971, after his divorce from his first wife, on a ski trip in Aspen, Colorado. They danced to five songs in a row by a band called Johnny Trash, and they knew they were in love. Jinger was 19 years old, ten years younger than Dick. She had been raised in Dumas. Her father, a wholesale car dealer, was a heavy drinker who drifted in and out of her family’s life. When Jinger was a teenager, he moved the family to Michigan. “I was the classic child of the alcoholic,” Jinger says. “I had to achieve things to feel good about myself.” She became editor of her high school yearbook, and she won the school’s best-dressed award because she never wore the same outfit twice. “I was obsessed with taking care of myself,” she remembers. “I used Jergens lotion on every inch of my body four times a day.”

A year after she met Dick, the two were married. Jinger lived the quiet life of a suburban baby-boomer wife—raising babies (two), redoing houses, and going to company dinners with Dick, whom she teasingly called Daddy Beauty Bucks. But in 1980 he asked her to be his partner at BeautiControl. Though she couldn’t give a tearjerker of a speech like Mary Kay and she didn’t have any Mary Kay–like stories about life in direct sales, she looked great, and she could talk a mile a minute. “I more or less said I would run the company and asked her to be the pretty face,” recalls Dick. Jinger had replied, “Drop dead.” She said she wanted to own half the company and be involved in overhauling the outdated line of BeautiControl cosmetics. She also made one more demand: She wasn’t to be known by her full name, Jinger Lee Heath. That sounded too much like Mary Kay Ash.

Dick agreed, but before long the two were arguing daily. As opposed to the Mary Kay philosophy, in which the consultants focused only on a woman’s face, Jinger said BeautiControl’s consultants should become head-to-toe image consultants. She suggested that the consultants offer free “color analyses,” in which variously colored cloths are draped under a woman’s face to determine which color best flatters her skin tone. That way, a woman would know exactly what shades of cosmetics would make her look better.

Dick nixed most of Jinger’s ideas. But by the end of 1982 he was broke and unable to make his $35,000 loan payment for that year. He went back to Tri-Chem and made a deal in which the company canceled the $35,000 debt in return for 50 percent of the company. He figured he had one year to prove himself and agreed to promote Jinger’s Color Analysis program. In one year, 1983 to 1984, the number of consultants tripled and sales leapt from $1,870,000 to $7,950,000. “Jinger had known what she was doing all along,” Dick says. Indeed, while Mary Kay had made a breakthrough as a single woman in a male business world, Jinger had made a breakthrough as a wife in her husband’s world. She updated BeautiControl’s line of cosmetics and attracted the kind of customers who one New York cosmetics industry analyst said were “a little bit more upscale” than the customers of BeautiControl’s competitors.

The Heaths, with the financial assistance of three prominent Dallas investors, bought back the other half of the company from Tri-Chem, and on March 6, 1986, they took BeautiControl public. Within days the price of the stock had rocketed from $16 to $24.75. Dick and Jinger quickly cashed in 25 percent of their holdings (they kept 46 percent of the stock) and made $25 million. Just like that, the Heaths had become Dallas’ ultimate nouveaux riches. They began paying themselves a joint salary of more than $1 million a year and built such an impressive mansion—complete with a wine cellar and a Versailles-like gardens—that Dallas tour buses began including it on their sightseeing tours. If the Heaths were hoping to be seen as the Napoleon and Josephine of cosmetics, the glorious couple out to conquer the industry, they couldn’t have come up with a better setting. Those BeautiControl consultants who met the sales and recruitment goals to become directors were rewarded with a trip to Dallas and dinner at the Heaths’ house. The women would start swooning the moment the Heaths’ English butler opened the front door and led them into a foyer with a 42-foot domed ceiling and ornate gold trimming around the cupola. Nearly trembling with excitement, they went upstairs to see the mansion’s pièce de résistance, Jinger’s three-story closet, twenty feet by twenty feet, with a circular staircase connecting one level to the next. Suspended from the ceiling were her evening gowns, each of which could be lowered at the touch of a button. In one clothes drawer were twenty red purses; in another were twenty gold purses. There were enough shoes stacked in one closet to make Imelda Marcos breathe orgasmically. The night I was at the home, a new director from Nashville, a former country music backup singer named Donna Faye Moffat, said, “I’m dying. Not even Reba McEntire’s house compares to this.”

Nationally, Jinger was getting great press, named by Glamour as one of the top ten outstanding working women and listed by Mirabella as one of America’s one thousand most influential women. But in Dallas some people tsk-tsked over her, calling her a flashy trophy wife of Dallas’ version of Georgette Mosbacher or Ivana Trump, a society dame who had let her ambition go to her head. It was odd to some that Jinger had built her French château in the very neighborhood where Mary Kay had built her own glamorous dream home, a 19,000-square-foot mansion that she painted pink. (Mary Kay’s pièce de résistance was a gigantic pink marble bathtub, which her consultants loved to stand in when they were given tours of the home.) Jinger and Dick began making significant donations to cancer research—which Mary Kay had been doing for years. Jinger and Dick even began attending the same North Dallas church that Mary Kay attended, the 13,000-member Prestonwood Baptist Church. The few times they saw each other in the hallways, they would nod politely but never stop and talk.

Jinger swears she was not trying to turn herself into another Mary Kay. “It’s ridiculous to set me up as a queen like her, because I’m just not that type of person,” she told me. “I publicly admit I have real problems. I cry. I have PMS. I go on and off diets like every other woman on the planet. I don’t do everything perfectly, and I don’t pretend to.” But to thousands of Middle American women who wanted something better for themselves, Jinger’s life seemed perfect. She was the woman who truly had it all—a beautiful family, a prosperous business, a castle to live in, a husband who stood by her side, and a closetful of great clothes. In a strange twist, Jinger Heath had become the embodiment of the message Mary Kay had been preaching for years.

Not only that, but just as BeautiControl’s fortunes took off, Mary Kay’s own sales took a dive. Between 1983 and 1985, sales at Mary Kay Cosmetics dropped from $323 million to $249 million, and the stock price of the company (which had gone on the New York Stock Exchange in the mid-seventies) plummeted from $40 a share to $9. In fairness, the crisis was not entirely the company’s fault. When the nation’s economy improves, as it was doing in the eighties, women who work part-time in direct sales tend to quit their jobs or find steadier employment in the conventional marketplace. Still, the performance of BeautiControl during that period indicated that something was wrong at Mary Kay Cosmetics. Industry analysts informed the press that while underdog BeautiControl was growing at a 20 percent rate, topping $50 million in sales by 1990, the pink Goliath’s growth was stagnant. “Is BeautiControl the next Mary Kay Cosmetics?” asked a Forbes article in 1989. “The next Avon Products?”

What few analysts or business reporters understood, however, was that Mary Kay Ash was prepared to give up her entire net worth to stay on top. In a major $450 million leveraged buyout in 1985, Mary Kay and her family purchased all the company’s publicly issued stock and took Mary Kay Cosmetics private. A new group of younger executives, brought in to handle the day-to-day operations, quickly updated the company’s image. The rather bland line of cosmetics was revamped and pretty young models were pictured in the product catalogs. The executives also boosted the commissions paid out to consultants to persuade younger women to leave their high-rise offices and join Mary Kay.

One of the company’s boldest moves was to introduce a version of BeautiControl’s Color Analysis Program, which it called the ColorLogic Glamour System. Suddenly, Dick and Jinger were crying that Mary Kay was copying them. Claiming they had the exclusive right to the “Logics” name—at the time, BeautiControl was marketing a line of skin-care products called SkinLogics and SunLogics—their lawyers sent Mary Kay Cosmetics a cease and desist letter for trademark violation. Mary Kay responded with a federal antitrust lawsuit, contending that the Heaths were “attempting to monopolize” the direct-sales cosmetics business.

The decades-old bitterness between the two companies came flooding back. Mary Kay’s attorneys insisted that BeautiControl was engaged in conspiratorial activity. BeautiControl’s attorneys said Mary Kay’s only purpose was harassment. In May 1991, when it became obvious that Mary Kay Cosmetics was unable to prove how BeautiControl, a company one tenth of its size, could monopolize the direct-sales cosmetics business, Mary Kay officials conceded defeat, abandoning the ColorLogic name (they changed it to ColorSelect). “The sole reason they went after us in the lawsuit was that we were doing too well and they were treading water,” Dick says. “Jinger would never have thought about such a vindictive move as a way to beat up on a little guy.”

But Mary Kay Ash was convinced that BeautiControl was the underhanded company, especially in its attempts to hire away Mary Kay staffers. “I don’t think that’s necessary,” Mary Kay told me. “It doesn’t show ingenuity.” Dick and Jinger can’t deny that they recruit talent from Mary Kay Cosmetics. In one of their splashiest coups, they hired Clifton Sanders, a former top chemist for Mary Kay, to run BeautiControl’s research and development division. Just before walking out of his office for the last time at Mary Kay, the expressive Sanders told his former bosses, “You can circle this day on your calendar, because your days of dominance are over.”

On and on the controversy goes, two companies that can’t ever escape one another. When Sanders heard that Mary Kay’s marketing chief, Curran Dandurand, had pooh-poohed BeautiControl’s new thigh cream that is supposed to help reduce cellulite, he bellowed, “I don’t give a rat’s ass what they say at Mary Kay” and tossed me an issue of Cosmetic Dermatology with a positive review of BeautiControl’s product. Earlier this year, when Mary Kay’s researchers trumpeted a new cosmetic called Triple-Action Eye Enhancer that supposedly causes a 23 percent reduction in the appearance of fine lines around the eyes, Jinger snorted that it was merely a copy of a BeautiControl product. It was BeautiControl, Jinger said, that received a rare patent this year on an anti-aging alpha hydroxy skin cream called Regeneration. “Oh, I doubt that patent has any value,” sneered Myra Barker, the chief scientific researcher for Mary Kay.

In Texas, where there are more than 36,000 Mary Kay salespeople and 8,432 salespeople for BeautiControl, the barbs between consultants are becoming especially pointed. One Mary Kay woman told me that BeautiControl is “a company of froufrous.” A BeautiControl woman snipped that Mary Kay consultants love big hair and heavy lipstick. The feud is gaining such notoriety that at the predominantly gay Halloween parade on Cedar Springs Avenue in Dallas, two men in drag always march together—one dressed as Mary Kay in a pink gown and a blond wig, and the other as Jinger in a Chanel suit with high heels and a BeautiControl banner draped across his chest. Throughout the parade, they call one another “bitch.”

Today Mary Kay Cosmetics is growing as it did in its early years. Its executives hope to triple the company’s size in ten years by pushing Mary Kay’s message to all corners of the earth, opening markets in less-developed countries such as China, where women are eager to find high-paying jobs. After operating for only two years in Russia, Mary Kay has seven thousand consultants and directors there who are doing an astonishing $10 million in annual wholesale sales. The top director in Russia, a 28-year-old former schoolteacher, will earn more than $300,000 this year, which could arguably make her the highest-paid woman in that country.

Though BeautiControl is also making an international move—this year the Heaths bought the assets of a privately held direct-sales company in the United Kingdom, which they will use as a base to start a European operation—it cannot begin to keep up with Mary Kay’s international growth. But Dick Heath says, “Remember we’ve got enormous opportunity left in the United States because only one out of twenty people in the country has ever heard of us. Everyone has been approached by a Mary Kay consultant. It’s going to be easier to sell cosmetics if you’re working for BeautiControl, because you’re going to be new.” Mary Kay, however, is not about to give up the U.S. market. This past year, the company purchased full-page advertisements in a variety of women’s magazines, such as Vogue and Glamour. “We’re letting the public know where it can find the world’s top cosmetics,” Dandarand says.

What is clear is that if BeautiControl is going to make a serious attempt to grab market share from Mary Kay Cosmetics, the best time to do it is when Mary Kay Ash steps down. Though Dick and Jinger won’t be specific about BeautiControl’s future expansion, they do admit they are considering a national campaign promoting Jinger. “Come on, what are they going to do?” says Tom Whatley, Mary Kay’s senior vice president of U.S. sales. “Run an advertisement of Mary Kay’s tombstone and say, ‘She’s dead, so come with Jinger’? It’s like saying the church and its teachings are invalid because Jesus died. Mary Kay’s teachings are enduring.”

To make certain Mary Kay’s teachings endure, hundreds of hours of videotape have been shot of her giving speeches at Seminar and other places, which can be replayed for years. There is also the Mary Kay Museum at the new corporate headquarters, where consultants can see a mannequin of Mary Kay, a short film of her life story, and even an exhibit of the ball gowns that she has worn to past Seminars.

But for now, Mary Kay Ash isn’t going anywhere. Although she is worth at least $325 million, she rarely socializes and does not like going on vacations. Her life is devoted entirely to her cosmetics kingdom. “What is it,” I asked her one afternoon, “that you want to do with the next ten years of your life?” “Just keep working,” she said with a shrug. She fell silent, as if she could hear the sound of Jinger Heath’s Mercedes a few miles away rushing toward BeautiControl’s office. “When someobody is out there waiting for you to fall over, it keeps you on your toes.”

Jinger says, diplomatically, that she is not waiting for Mary Kay to fall over. “I’m simply trying to run a good business, not take over the world,” she says. “I’ll be honest: I don’t want to spend all my waking hours on BeautiControl. I want to spend time with my daughter, who is eleven. My gosh, I want to enjoy other things.” She pauses and then cannot help herself from taking a last shot: “I hope Mary Kay is getting to enjoy something.”

After spending time with Mary Kay, I have wondered if the reason she is so intent on telling her consultants to keep their priorities straight—her motto for the company is “God first, family second, career third”—is because she has learned the price of commitment to work. Today she is essentially alone, just as she was years ago when she was starting out. She has moved from the famous pink mansion she built in the seventies and returned to her older six-thousand-square-foot house that she owned since the sixties. Except for the security guard who stays in an apartment out back, she lives by herself. She rarely gets out except to go to work or to go shopping at her neighborhood Tom Thumb. Immaculately dressed, her diamond rings on her fingers, she slowly pushes a metal cart up and down the aisles, the security guard trailing a few steps behind her, grabbing any food that she has forgotten. Last summer she told me that her 53-year-old son, Richard, who has been playing a less active role in the company for the past few years and enjoying his money, had invited her to take a friend to the new beach home he had just finished building in Baja California. Mary Kay thought for a moment and then confessed that she couldn’t think of anyone she wanted to take.

Perhaps Mary Kay keeps working to make sure Jinger Heath will never take her throne. Yet it is also obvious that her cosmetics kingdom is a refuge, a place where she has found a life without disappointment—where men are at a distance, where women make the money, where cosmetics can hide anyone’s blemishes, and where she is queen. “I feel that God has led me into this position, as someone to help women to know how great they really are,” she told me. When I asked if she would ever quit, she shook her head almost wistfully and said, “They’ll have to carry me out of the building.” Then, lifting her chin, she gave me one of her famous glares. It was the triumphant stare of a woman who had beaten back her enemies—who was still beating back time, and youth.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas