There are those who want the cowboy boot to go away. After all, Texas is a booming industrial and banking center, and its inhabitants should be expected to assume a certain amount of urban decorum and style. Kickers and goat ropers wear cowboy boots; bank presidents do not. Yet there is the old boot at the top of the fashion scene, and not just in Dallas but in New York and San Francisco. The cowboy boot is about to do for Texas taste what Jimmy Carter has done for Southern Democrats: make it universally respectable.

What is it about cowboy boots that has pushed them up the fashion ladder? After all, they have been around for over a hundred years and will probably be around for at least another hundred. People who are wearing them now wouldn’t have worn them to their own funerals five years ago; today men and women both are standing in line to buy a pair. The biggest reason behind the boot’s new respectability is the rise of Texas chic, that plus the fact that cowboy boots are recognized worldwide as a Texas symbol. Wear cowboy boots in Europe, Asia, or South America and you’re not from the USA, you’re from Texas. Perhaps even more than the cowboy hat and shirt, a pair of boots is quintessential Texan and, by extension, quintessentially American. Until recently, this was something that a lot of native sons tried to sweep under the rug, but now, thanks to Willie, Jerry Jeff, progressive country, and—yes, even to Lyndon—it’s become a source of pride rather than acute embarrassment. Texas chic, our homegrown variety of redneck chic, is just the natural outgrowth of the cowman and the hippie being friends.

In another sense, though, the Texas cowboy has always been America’s national hero. Big city Texans may have been a little uneasy about acknowledging this uncouth character, but the rest of the country quickly made him a legend. The process, which began with penny dreadful western novels and Wild West shows, culminated in the fifties with the Age of the Western. In those days every other feature at the movies and on the tube was a horse opera, people knew Doc and Miss Kitty better than their own neighbors, and every kid in America knew how to die, western style: clutch hand to chest, gasp and utter a profound cliché, buckle knees, hit ground sideways, play dead, come back to life and fire again. Today those mass-media children are adults with money in their pockets, and it just could be that they’re trying to revive one of two things: their lost childhood or their lost heroes. Gene Autry and Champion; Roy Rogers and the era’s most famous piece of horseflesh, the late Trigger; Paladin and his well-mannered hired gun; The Rifleman; Matt Dillon—they’re extinct and practically forgotten now, but for half a decade they were all but canonized, as multitudes of small boys assiduously copied their every gesture, habit of speech, and piece of clothing. Now that those kids are grown up, it’s not too surprising to find them wearing cowboy boots on the streets of New York as well as the streets of Laredo.

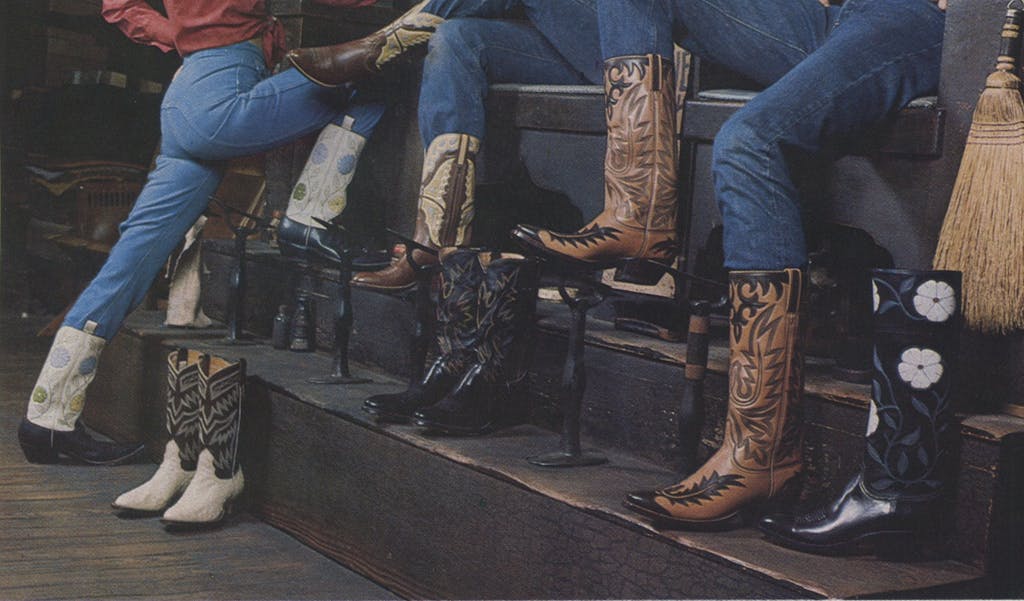

Boots have changed, though. They still have the high arch—the indispensable feature that makes them cowboy boots—but almost everything else is in a state of flux. It used to be that you could tell by his boots if a guy was a cowboy, but with everybody wearing them these days, it’s not so simple. There are a few clues, though, that will help you tell the real true-grit cowboy and the rodeo star from the cheap imitation cosmic variety. For an old-time range rider (scarce though he is) boots are not a sometime thing. He has them on sixteen hours a day, seven days a week. They’re long and tall, and the only difference between the ones he wears to punch cows and the ones he wears to the Saturday night dance is the color—brown for work, black for dress. For the most part his boots are plain calfskin, rough side out for work, and maybe a little alligator to spruce up the dressy ones. Unless he’s an oilman, he doesn’t go in for exotic leathers like anteater, though he will opt for several rows of decorative stitching at the top, claiming that it makes the boot hold up better. He’d be hard pressed to admit that he just liked the way it looked.

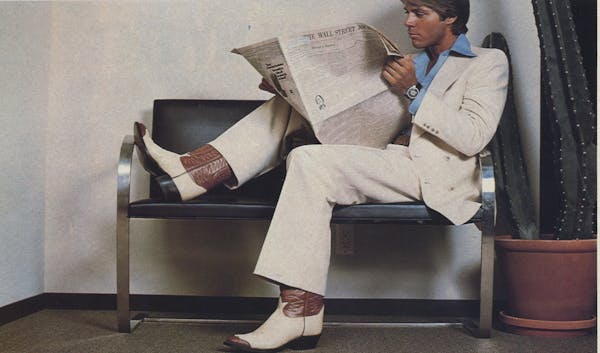

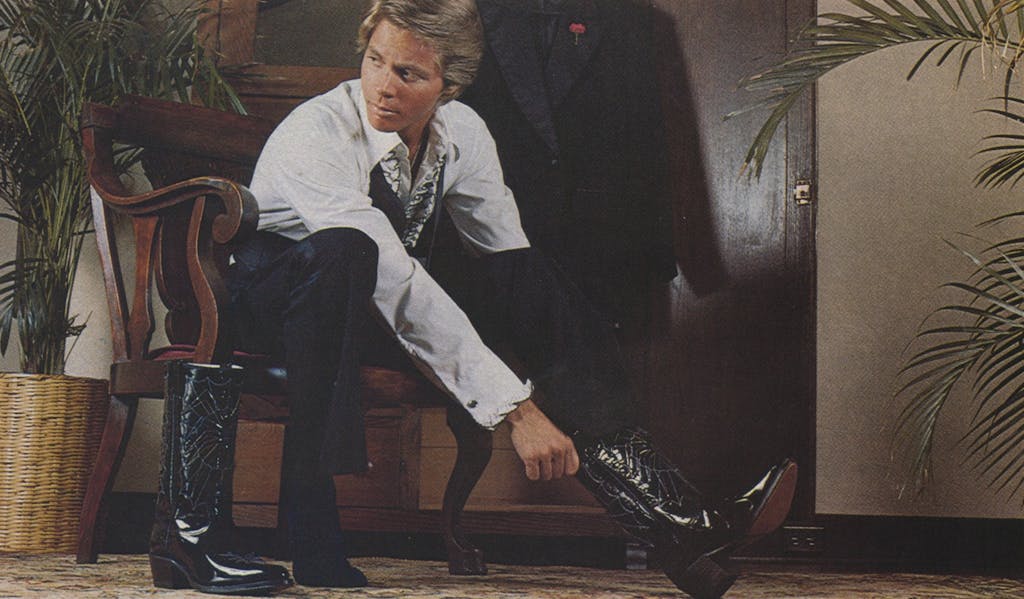

The rodeo rider, a cowboy of sorts, wants footgear that he can dig into the dirt or snare a stirrup with, so like the genuine range rider, he prefers a needle toe and tall riding heel. But he’s also a showman and needs to stand out in a crowd, so he goes for wild colors and ostentatious designs that would make an old-timer blush. The cosmic cowboy is still another story. Since he’s beating the pavement selling insurance or dealing dope all day, he needs a walking heel and a round toe so his feet won’t end up in an inert pulp by 5 p.m. He’s attuned to fashion—that’s why he’s wearing boots in the first place—and if wing-tip boots were big with all his buddies this year, he’ll have a pair in the closet. The only real problem in telling the cowboys (real and rodeo) from the cosmics is that there’s been some cross-pollination between them lately. The cowboys are easing into lower heels and rounder toes while the cosmics are tottering around in high-heeled boots just like the real McCoy.

Not only is the shape of the cowboy boot changing; the leather is different, too. Back in the old days the cowboy just wore the hide of one of the animals he’d driven to market, and calfskin still accounts for the vast majority of boot sales. But the profits are higher, and demand is growing, for the exotics: anteater, ostrich, shark, alligator, iguana, and South American lizard, not to mention elephant, cobra, and (until it was banned) kangaroo. If it walks, crawls, swims, or gallops, you’ll probably find its hide tanned and on somebody’s foot. Despite their high price ($300 and up) the exotics are becoming increasingly popular; but they have their critics, because inevitably, endangered species of animals are threatened. One of the most modish, sea turtle, is brought in from Mexico where the killing of the animals is regulated by the government. However, there is some doubt as to the effectiveness of this regulation, which has led several states (including Texas) to ban the sale of certain types of sea turtle skins. Ironically, the appeal of the exotic leathers is based solely on fashion, not function. “The price doesn’t have anything to do with the quality of the boot,” says Bill Powers, sales manager for Justin. “A calfskin boot selling for $75 to $80 will be as good as you can get for $300 in anteater. The exotic leather doesn’t make it a better boot.”

The question of why the boot, rather than the string tie or rattlesnake hatband, should be making it big in fashion these days opens up yet another dimension of boot stylishness. There are any number of typical cowboy duds, but only boots are “in.” Why? In a word, because they’re macho. Without getting too clinical, it’s easy to see that a long-toed, high-heeled, form-fitting boot has a lot more going for it than a pair of loafers. According to William A. Rossi, author of The Sex Life of the Foot and Shoe (Saturday Review Press/Dutton), boots are more than just sexy, they’re a little psycho, and anybody who’s wearing a pair of them might consider seeing a shrink. Rossi outlines five categories of men’s shoes: the sensuous shoe (usually European, lightweight, made of soft supple leathers with thin, close-edged soles); the peacock shoe (platforms, high heels, bump toes, and “a touch of rococo”); the masculine shoe (wingtips, loafers, and (!) the white shoe); the eunuch shoe (almost always black, plain toe, usually laced, a “sterile, desexed” shoe); and the machismo shoe (including cowboy boots). Rossi blew his chances of ever being enshrined in the Cowboy Hall of Fame with his description of the boot: It “lacks the subtle eroticism of the sensuous shoe, the colorful imagination of the peacock shoe, the feigned boldness of the masculine shoe, or the recessive character of the eunuch shoe. Instead the machismo shoe is one of the most savagely sex ridden of all male footwear styles—chauvinistic, aggressive, sadistic. For macho shoe wearers it isn’t enough merely to be or appear masculine. They must stomp this impression into the minds of others, especially females. . . The cowboy boot . . . has its own machismo character, the cowboy and his boots representing an image of aggressive male thrust, or hardy toughness.” Then the clincher: “The gladiator character of the boot itself feeds the undernourished sexual ego of the wearers.” Try repeating this academic nonsense out in San Angelo, or even in River Oaks, if you want to test its essential truth.

It’s not just the boot’s style and sex appeal, though, that has kept this seemingly archaic piece of leather around for over a hundred years. Long before Fifth Avenue heard of them, long before television was even invented, boots were being ballyhooed because they were practical and good for your feet. According to this popular myth, the tops are high and leather thick to protect against cow paddies, mesquite thorns, and snakebites while the wearer is taking a little relief in the brush. The toes are pointed to angle easily into and out of his stirrup, while the slanted heel hooks securely onto it for better riding. But considering that there are probably more Future Farmers and truck jockeys in boots these days than there are cowboys, the so-called practicality dissolves into just so much hype. After all, more work is done in Texas on top of a John Deere or in a semi than on top of a cow pony. The one exception that does make the boot genuinely practical for ranch, farm, or truck is the four-and-a-half-inch shank running down the arch of each foot. This makes it perfect for double-clutching a big rig down the interstate and keeps your foot from bending like a noodle around the blade of a shovel when you’re breaking ground for the new hen house.

The other half of the practicality legend is that boots are comfortable. Boot addicts swear by them, but first-timers will tell you that the shank under the arch makes it feel like you’re standing on a pole and the fit is so very snug that for sheer discomfort it favorably compares to Chinese foot-binding. Ray Villarreal, owner of the Footfit Shoe Store in El Paso, is one of thirteen shoemakers certified in pedorthics in Texas, which makes him kind of a medical cobbler. He doesn’t have many kind words for boots. According to him, “Boots are fine for fashion, but when it comes to a foot problem, to me personally they’re a no-no. My brother and I see a lot of patients every year and I’ll tell you, if they’re wearing boots, I’m going to take them right off and put on shoes.”

He’ll never convert a boot junkie. Even after the comfort myth has been debunked and the fad has faded, he’ll still wear them for the reason that people have always worn cowboy boots—mystique. Part of that appeal is the new Texas chic, of course, but more than that it has to do with the boot’s honorable place in Texas’ heritage and the history of the state’s famous bootmaking families. The evolution of the boot was a gradual process, starting with the first cowboys (the Mexican vaqueros) and culminating in the cattle drive era of the 1860s and ’70s with the high-heeled, steel-reinforced boot that we know today. Refinements such as pointed toes, grips, decorative stitching, and exotic leathers came later.

Because of the demand by cattle drovers for good-fitting, custom boots, bootmakers began to locate along the cattle trails. Most of these one-man shops died with the coming of the railroad and the end of the big cattle drives, but others changed with the times and are still alive and kicking today. There are several distinct levels of bootmaking in Texas, from the historic one-man one-boot operation to the assembly line. The single craftsman avoids machines, while the large manufacturer prefers them.

One assumes that machines can’t do it right, the other that machines can do it better. The best is somewhere in between, because the standard of comparison is not only financial but also philosophical. After all, a Rolls-Royce and a Ford will both get you where you’re going. The difference is a matter of money and taste.

It’s not surprising to find that Texas has a lion’s share of the $200-million-a-year boot market in the United States. What is surprising is that Texas shares that market with, of all places, Tennessee. That state has the big-volume bootmakers, including Acme, Durango, Wrangler, and (sacrilege!) the Texas Boot Company. It is ominous that Acme (the country’s largest boot manufacturer, cranking out an estimated 38,000 pairs a day) has purchased a plant location in El Paso. When it comes to quality, though, all the brand names are rooted in Texas. Tony Lama (El Paso), Justin (Fort Worth and El Paso), and Nocona (Nocona, 40 miles east of Wichita Falls) are the big three in Texas, turning out a total of 8300 pairs a day. El Paso also hosts, among others, Cowtown, Sanders, and the Larry Mahan boot companies. Other notable bootmakers are scattered: Sam Lucchese in San Antonio, M. K. Leddy in San Angelo, J. K. Norfleet (formerly Dixon) in Wichita Falls, and in the Valley, Rios of Mercedes. The major Texas makers started as family operations and they still retain a personal interest in quality of the product they turn out. Although the big companies all employ some machines in the manufacture of their handcrafted (as opposed to totally handmade) boots, they haven’t yet been seduced by the profits to be had by mass marketing through self-service chain stores, as has Acme of Tennessee. Upping sales would call for going to more machine processes, and this they’re not willing to do. For the most part they are satisfied with selling their products strictly through western-wear outlets.

Even before Charlie Dunn retired, there weren’t many craftsmen who could singlehandedly make a boot from scratch. Tex Robin of Coleman is one of that vanishing breed. He can make three to five pairs a week and gets about $125 for basic calfskin boots. A quiet man who is a little hesitant with strangers, Robin started working in his father’s bootmaking shop when he was ten years old. He’s now 36 and, despite his skill, he’s usually four or five months behind. To order a Tex Robin boot you have to go to Coleman, about 50 miles south of Abilene, to be sketched and measured. This cuts his list of customers down to those living within a 100-mile radius, mostly ranchers and salesmen. Although Robin has plenty of business, he does appear to be the last of his family in the profession. His two daughters have shown no interest in making cowboy boots.

James Leddy of Abilene is another bootmaker who works from scratch, though he has a somewhat larger operation than Robin. Leddy and his wife Paula, together with Raymond and Colleen Blasingame, turn out about twelve pairs a week. The Leddy brand has been around a long time, even though James is only 38. Nine brothers put together the M. L. Leddy Boot Company in Brady in 1921. Since that time the Leddy name has been associated with shops in San Angelo, Fort Stockton, Menard, Tulsa, Fort Worth, and Grand Prairie. Like Robin, James Leddy started out in his father’s shop, at age twelve. Seventy-five per cent of his customers are ranchers and oil men within a 200-mile radius of Abilene, while the other 25 per cent are from out of state. He has no desire to expand the business. Having once spent some time developing a high-quality line for Cowtown Boots in El Paso, he left when the company decided they could turn a better profit by making more boots of lower quality. “You have to enjoy your work,” says Leddy reflectively.

It takes six months to get a pair of James Leddy boots. But a lot of people, including Buck Owens and Jimmy Dean, are willing to wait. Each pair of his boots reflects about $50 in labor and a minimum of $40 in material. They cost $125 to $350. “We make a living, though not a good living,” he says. “I work probably a minimum of a 60-hour week. It’s not a get-rich-quick thing.” Leddy’s customers usually go to Abilene for the ritual of foot tracing and measuring. Then they wait. It takes Leddy hours to do what the larger manufacturers can do in fifteen minutes with the help of machines but, as Leddy says, “A man can sew the inseam on a boot better than a machine if he’s doing one or two pairs a day.”

One step away from the one-man one-boot shop is the Lucchese Boot Company of San Antonio, which since 1970 has been affiliated with Wrangler Boots and Jeans. There, in a two-story brick building six blocks from the Alamo, Sam Lucchese (grandson of one of the six brothers who founded the company in 1883) and 300 workers manufacture 40 pairs of boots a day. Half of the boots are custom-made, while the other half are sent as stock items to western-wear stores. Lucchese has always specialized in custom bootmaking and even now makes the shelf stocking line only when it suits him. His custom calfskin boot starts at $300 a pair, the ready-made calf at $150. Lucchese is famous for style and quality, and for his leather. “But we’re not talking about hamburger leather. McDonald’s dictates what a lot of boots are made of; the more hamburgers they sell the more hamburger leather on the market. We make ours of imported French or Italian calf. It’s like the difference between a baby’s skin and that of a 40-year-old man.” Lucchese finds himself somewhere between the wholly handmade and the mostly machine-made boot. He doesn’t put in as much handmade time as the small shops, but he still has fewer machine processes than Justin and Tony Lama. “The day of the single person putting together a whole boot is all but gone. My grandfather found, back in the 1890s, that some craftsmen are very good at making tops and others are very good at making bottoms. It just makes more sense to put them together on the same boot.” There have been a lot of famous feet in Lucchese boots (LBJ, John Wayne, Will Rogers, Teddy Roosevelt, and Baron Guy de Rothschild); also some who wanted to be but aren’t. Cher Bono Allman once saw a pair of $1200 anteater and hornback lizard boots made by Lucchese and tried to order some. “I had to disappoint her,” Lucchese said. “Women’s feet expand and contract like an accordion, and since my grandfather’s death we have preferred not to make boots for them.” Relenting a bit, he explains that he could have custom-made the boots for Cher, but she would have had to come to San Antonio for measurements. The company’s early business records and outline books, including Very Important Feet fitted between 1897 and 1940, are now in the Barker Texas History Collection in Austin. Not surprisingly, Lucchese is also known for producing the most overstated, ostentatious, gaudy boots in the state. The Tom Mix Movie Star Line features inlaid leathers with multi-colored butterflies or purple and green flowers, depending on the buyer’s taste, or lack of it. First made in the forties, a pair of Tom Mix boots now starts at $400.

Once past the distinctive Lucchese boot, one enters the realm of the big three—Tony Lama, Justin, and Nocona. Here the philosophy of bootmaking changes, for these bootmakers put more faith in machines than do the small operators, without, in their judgment, significantly sacrificing quality. Tony Lama opened a boot repair shop in El Paso in 1911. Since that time his boots have become the state’s best-selling label, and he has booted such eminent feet as Evel Knievel’s, Marty Robbins’, and the Shah of Iran’s. A native of Syracuse, New York, Lama learned much of his trade as a cobbler with the U.S. Army; he was with General John Pershing when the Cavalry stormed into Mexico looking for Pancho Villa. When he died in 1974, Lama left the company in the hands of sons Joe, Louis, and Tony, Jr. Last year the business had net sales of $24.2 million. They currently turn out 3200 pairs a day—which retail at $70 to $120—and their target markets are expanding beyond the farmers and ranchers who were their first customers (and who are still the backbone of the business). Horseback riding is becoming increasingly popular, which means a lucrative market among pleasure riders. Lama is also adding a night shift to step up production on a relatively new line of children’s boots, which retail at about $30 a pair. Up until now the Tennessee bootmakers have controlled the children’s trade, with boots priced at $7 to $12 and up. Lama’s product is thus pretty expensive for a pair of kid’s shoes, yet orders are so backed up that if they weren’t in by this May there was no chance for delivery by Christmas.

In 1879 H. J. Justin started making boots in Spanish Fort, a Chisholm Trail town on the Oklahoma border. Around 1890, when the railroad bypassed the little community, he moved the works to Nocona, not too many miles away. The business grew, attracting a variety of customers—including Jack Benny, Bob Lilly, and Rusty Wier. One favorite family story is that Justin liked to brag that three cattle rustlers once hanged in Wichita Falls “died with their boots on, and all of them had on my boots.” In 1918, the year “Daddy Joe” Justin died, sales hit $100,000. Not long after this, his sons voted to move Justin Boots to Fort Worth for better banking and transportation facilities. In the 51 years since the brothers left for Cowtown (in 1925) the Justin Boot Company has grown and become part of a conglomerate. In 1925 sales were $200,000. Last year the figure was $23 million, a growth in the last ten years alone of 267 per cent. According to the company’s management, Justin’s Fort Worth and El Paso operations produce 3000 pairs a day.

But that’s not all the Justins produce. Realizing that there was limited expansion potential in the quality cowboy boot field and refusing to go after the cheap mod boot market, Justin Boots expanded in other directions. Now under the hand of Daddy Joe’s grandson, John Justin, Jr., the company is into brick, concrete, a book-printing press, and ceramic cooling towers. Thus the descendant of the one-man boot shop in Spanish Fort earned $69.4 million in sales for Justin Industries in 1975.

The Justin family tradition of business know-how and spunk extends to the female members as well. In 1925 when the brothers moved the boot business to Fort Worth, their sister Enid simply refused to go. Sustained by her personal credo—“Daddy Joe would have wanted it that way”—Miss Enid borrowed $5000 and personally started the Nocona Boot Company. “At first cowboys scoffed at the idea of buying boots from a woman,” she says. “I kept the company going by turning my home into a rooming house, selling coal, and serving as shipping clerk, stenographer, and credit manager combined.” The company flourished when oil was discovered near Nocona. Skeptical cowboys heard roughnecks and oilmen talking about Nocona boots and soon began to patronize the business. Today the indefatigable Miss Enid is up each morning at 5, eats breakfast in her brightly painted pink house (with the cowboy boot weather vane), and drives her white Fleetwood Cadillac (custom plates EJ BOOT) to the office. By 7 a.m. she’s started opening her mail. Shalimar perfume, double dabs, is a personal trademark of Miss Enid, a spry woman with blue hair and tinted glasses who is quite aware that she is the only female near the top in the macho world of cowboy boots. She likes to mention that Nocona’s clientele has included Harry Truman, Sweden’s King Gustav VI, John Connally, Henry Ford II, George Burns and Grade Allen, and Glen Campbell. People spent over $8 million last year on Nocona boots.

Where will the boot go from here? Now that it’s hit the big time, the logical direction is down. Will boots be as déclassé next year as bolo ties and western-tailored tuxes? Yes and no. Naturally they can’t stay at the top of the fashion heap indefinitely; a year from now those fancy New York boots will be sharing space in the back of the closet with three-inch platforms. But while New York may forget, Texas won’t. Texans will wear boots, just as they always have, because boots are part of Texas. Like the King Ranch, oil wells, and the Astrodome, boots we will have always with us. And just give them time. In 1986 they’ll be on Fifth Avenue again as part of the Great American Cowboy Boot Revival.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Fashion

- Cowboy Boots