In the lobby of a small, exclusive hotel on Manhattan’s East Side, a limo driver and a bellman quietly discuss the whereabouts of Lyle Lovett. “Have you seen him?” asks the driver.

The bellman nods. “Came through just a few minutes ago.”

“Was he with his friend?” asks the driver with a slight, coded smile.

The other’s smile is smug with fresh knowledge. “No. Another friend.”

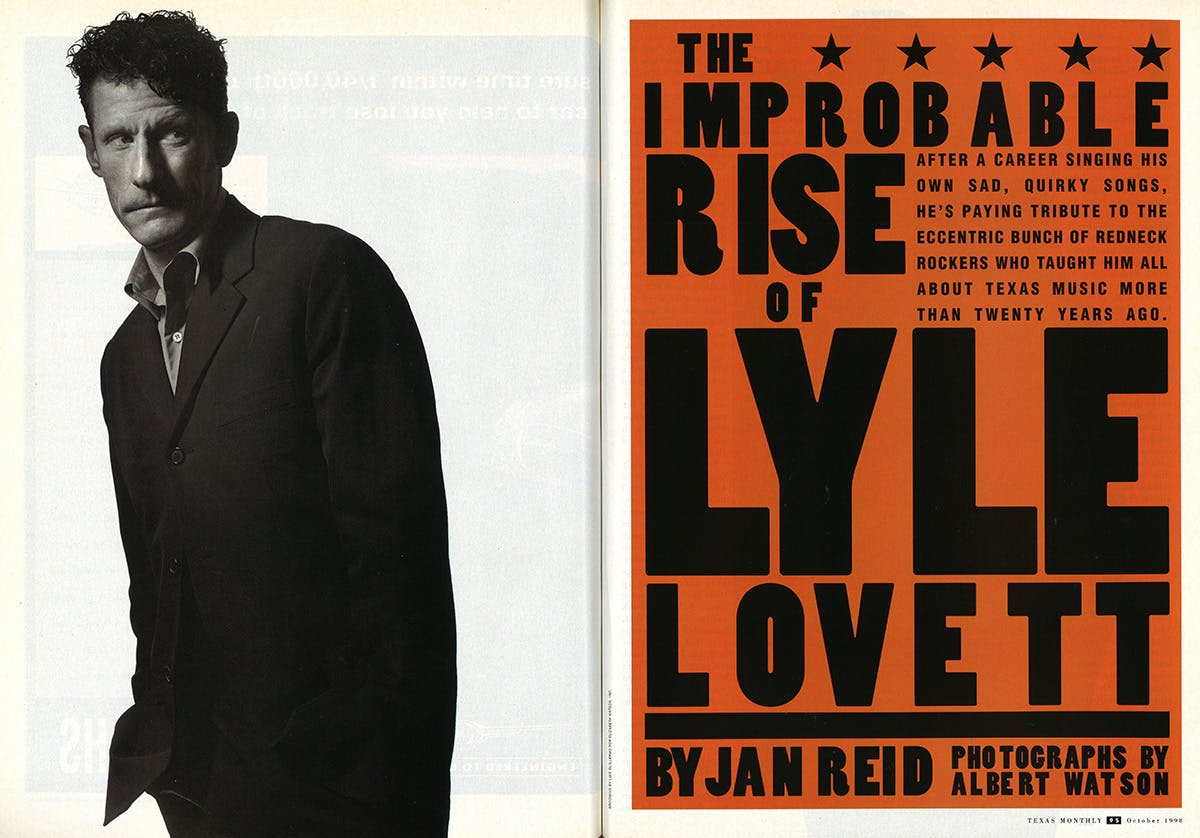

I find him upstairs, in his suite. He comes forward in a black shirt and trousers with a handshake offered and his long mouth parted in a grin. The man who married movie star Julia Roberts—and became an inspiration for every guy who ever thought himself homely—is slender with a large craggy head. His distinctive broomcorn shock of hair is lightly oiled, and at forty, he shows a little gray in the sideburns. Many women have told me they find Lyle Lovett very attractive. He is vain enough about his curious looks to tell photographers he favors the left side of his face. The left cheek is deeply furrowed, and he cocks the eyebrow with sly effect.

Lovett and I have communicated and made overtures in the past but never met. The occasion this August day is the release of his seventh album, Step Inside This House (Curb/MCA). The two-disc, 21-song set contains none of Lovett’s own material but is a tribute to the Texas songwriters who shaped his style—among them, Guy Clark, Michael Martin Murphey, Walter Hyatt, Steven Fromholz, Townes Van Zandt, and Willis Alan Ramsey. It’s an indication of Lovett’s stature in the music business that he can release a double album of songs written by relatively unknown songwriters. But he has often done the strange and seemingly impossible in his career, defying every category and format yet still selling millions of albums and packing concert halls—despite rarely getting on the radio. Almost in spite of himself, Lyle Lovett is a star. For me, the songs on Step Inside This House bring a rush of nostalgia for a magic time in Austin 25 years ago, long before Lovett’s hairdo became a national topic of conversation. “The first time I encountered these songwriters was reading about them in your book,” Lovett tells me. “I learned to play the guitar listening to some of these songs. For me, this record is going back to the beginning. It’s kind of like taking stock and starting over.” lovett rests his arms on a conference table and watches me take materials out of a briefcase. “It’s interesting to be introduced to people by reading about them,” he remarks, “and then learn about them by listening to their work. No matter how well you get to know them later, there’s something about that quality they never lose.”

My book, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, grew out of an article published in this magazine in 1973, the first year of its existence. My publisher was David Lindsey, a genteel man who would later go on to write best-selling crime novels. We thought that we were onto the hottest cultural uprising since Haight-Ashbury. As I chased between night spots in Austin, Dallas, and Houston and wrote about musicians with their records blaring on my stereo, Lindsey pestered me for a title. I could roughly define this new Texas music—a fusion of rock and roll, country and western, folk, blues, and gospel—but I couldn’t name it. An Austin radio station that aired the music called it “progressive country.” To me that sounded like some political naïf’s wishful thinking. One day in Lindsey’s office I announced a breakthrough. I waved my hand like a band director, indicating the rough spots that could be filled in later: “Da duh da duh da duh . . . of Redneck Rock.”

It may be the only original idea I have ever had, and I still don’t know what it means, exactly. But the live music scene centered in Austin seemed to have a strange quality that brought adverse elements together. Hippies and cedar choppers were kicking up their heels in the same dance halls. My book captured some of that, particularly in the chapters that profiled the singer-songwriters. I thought afterward that I should have learned more about their musicianship and printed fewer of their lyrics, but with the benefit of even further hindsight, I was right to do it the way I did. It really was more about language than guitar licks. The songwriters who grabbed young Lyle Lovett’s attention crafted some exceptional poetry. Unfortunately, the handful of radio stations that aired this crossbred Texas music soon moved on to other formats. Commercially abandoned, the musicians who had been celebrities in Austin were unable to do with their careers what Lovett has accomplished with his. Many of them left Texas—Clark, Murphey, Van Zandt, Hyatt, Ramsey, Gary P. Nunn. Jerry Jeff Walker eventually salvaged his livelihood by sobering up and becoming a cult figure on college campuses. First B. W. Stevenson, then Hyatt and Van Zandt died before their time. Kinky Friedman can still bring down a house with his outrageous tunes, but he prospers because he writes best-selling mystery novels featuring a wise-guy detective named Kinky. Willie Nelson was the only one of the redneck rockers who truly became a national figure, and he had laid the floor for that with his Nashville songwriting in the fifties and sixties. Austin was permanently established as a live music mecca and proving ground for performers on their way up, but the scene I wrote about withered just as quickly as it had flowered.

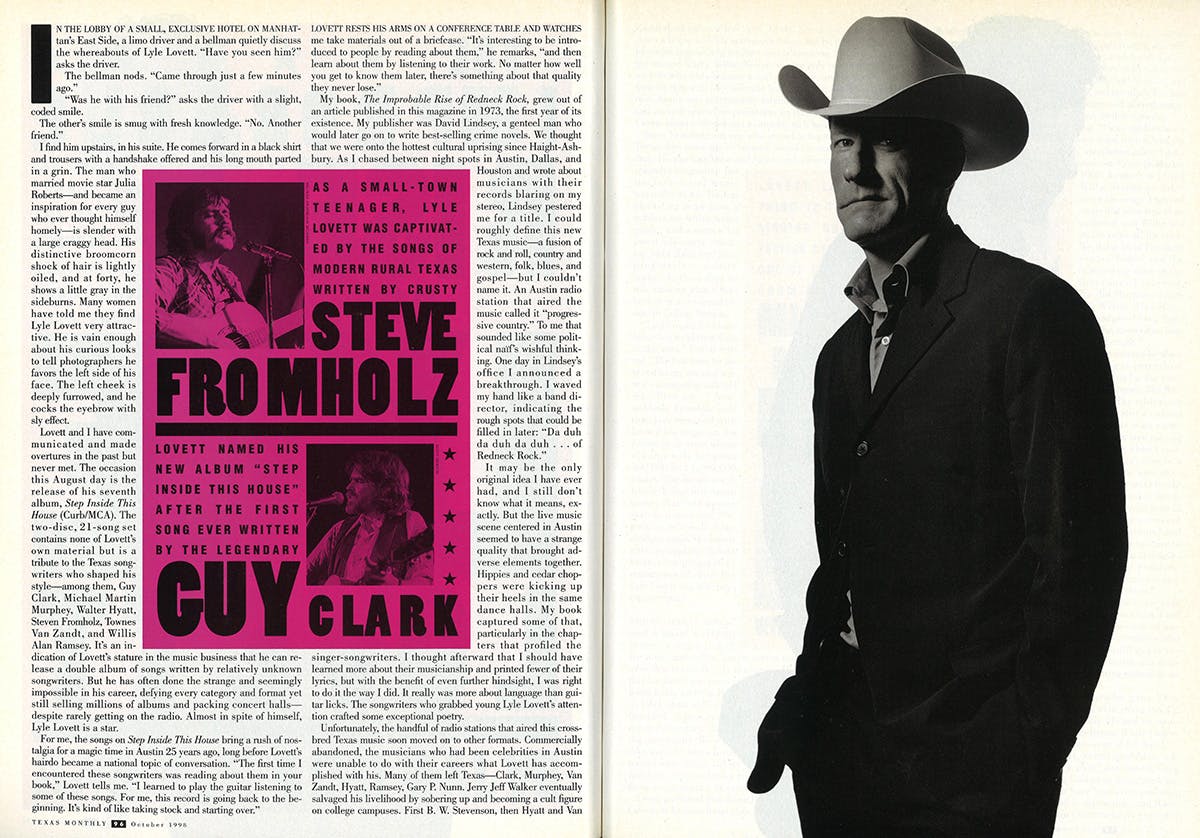

Steve Fromholz was one who stayed in town and kept playing. Twenty-five years ago he seemed poised for some measure of stardom. He was handsome and funny, had a fine baritone, and was a splendid songwriter. But the fashions of music passed him by. He has carried on as an actor, a wilderness white-water guide, and a somewhat jaded folksinger, cracking jokes about the “great progressive-country scare.” In those days he was unaware what a hero he was to a novice musician in College Station.

“I got to open for Fromholz when he played clubs in the area,” Lovett tells me. “The first time, he listened to my set and was real encouraging and told me, ‘Nice job.’” Now, suddenly, Fromholz finds the favor returned with four of his songs on the record of an artist whose albums sell between 500,000 and 1,000,000 copies. The royalties will likely bring him more money than he has ever seen as a musician. “I’m going to be a multi-thousandaire again,” Fromholz tells me, laughing. “I don’t know what progressive country was all about. But Lyle Lovett was sure paying attention.”

THE DOORBELL RINGS, and a hotel bellhop comes in with a tray of ice water and coffee. Lovett serves the coffee with a mannerliness that seems deeply ingrained. He often mentions proudly that his family has been in Texas since the 1840’s. He makes his home today north of Houston, in a house his grandparents built in 1911 in an enclave of kinfolks living on parcels of divided farmland. “I grew up around Spring when it was still very much out in the country,” he says. “It was just an unincorporated farming community. We were watching the city come out to us and take over. So when I read about Steve Fromholz and found the record with ‘Texas Trilogy’ [a trio of songs featuring hard-luck ranchers, boyhood train rides, and the tiny burg of Kopperl] those songs meant a lot to me. They spoke to my upbringing.”

Lovett graduated from Klein High School and went to Texas A&M University because it was close to home. He lived in a dorm and fell in with others who spent the evenings trying to learn to play a guitar all the way through a song. He befriended an English major who also had a bright future in Texas music—Robert Earl Keen. Lovett served on a student union committee that booked performers into the campus coffeehouse. “The first time I saw Michael Murphey was in 1975,” he says. “He came out by himself, and the whole first half of the show, just stood there and told stories and played songs. I thought, ‘Man, I want to get to where I can do that someday.’”

His chance to learn wasn’t long in coming. “I was eighteen when I first started performing,” he says. “I came home from school the summer of 1976, and along with a buddy who played guitar, I got a job in the bar of a restaurant close to home, on Farm-to-Market 1960. As much as I liked Willie Nelson, we didn’t cover his songs. I wanted songs that were new to an audience, and Willie was on the radio all the time. We did a lot of Fromholz songs. ‘Bears’ and the trilogy were some of the first songs I learned. We did Murphey songs and Willis Alan Ramsey songs—I sang ‘Spider John’ more times than I could count.”

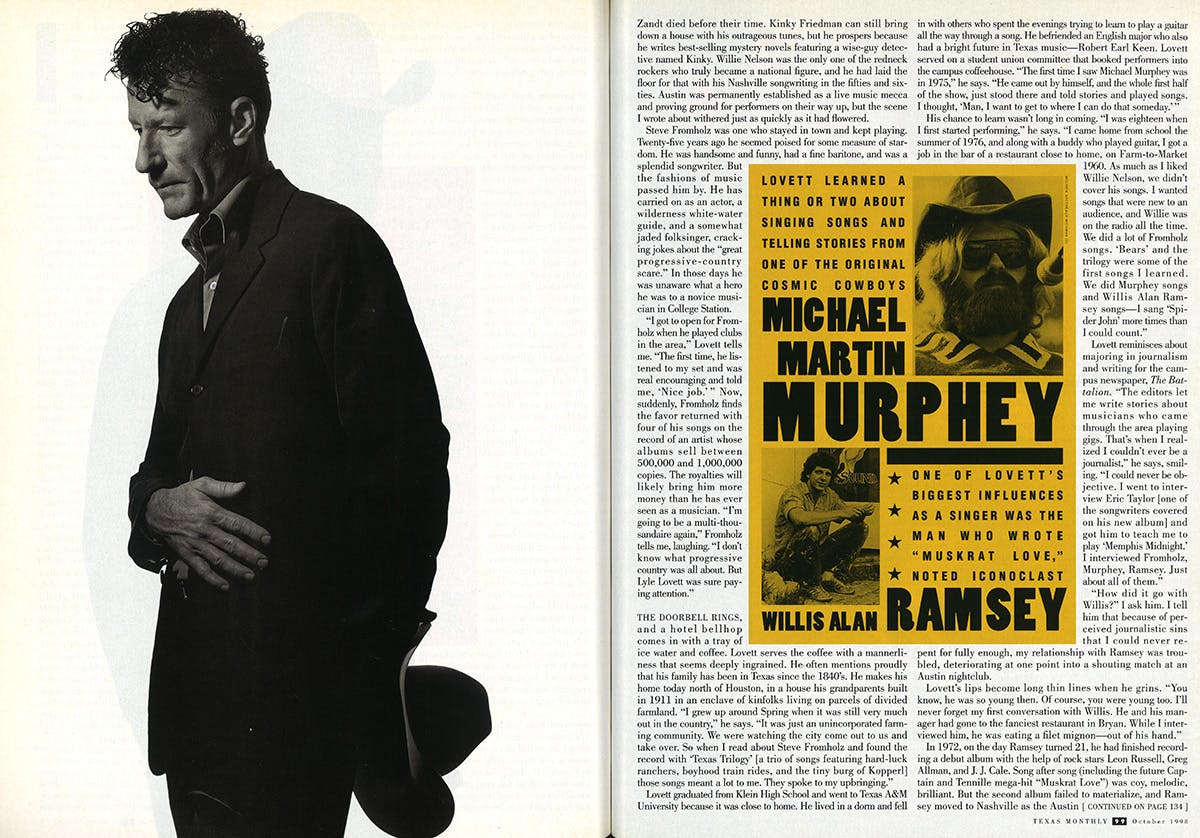

Lovett reminisces about majoring in journalism and writing for the campus newspaper, The Battalion. “The editors let me write stories about musicians who came through the area playing gigs. That’s when I realized I couldn’t ever be a journalist,” he says, smiling. “I could never be objective. I went to interview Eric Taylor [one of the songwriters covered on his new album] and got him to teach me to play ‘Memphis Midnight.’ I interviewed Fromholz, Murphey, Ramsey. Just about all of them.”

“How did it go with Willis?” I ask him. I tell him that because of perceived journalistic sins that I could never repent for fully enough, my relationship with Ramsey was troubled, deteriorating at one point into a shouting match at an Austin nightclub.

Lovett’s lips become long thin lines when he grins. “You know, he was so young then. Of course, you were young too. I’ll never forget my first conversation with Willis. He and his manager had gone to the fanciest restaurant in Bryan. While I interviewed him, he was eating a filet mignon—out of his hand.”

In 1972, on the day Ramsey turned 21, he had finished recording a debut album with the help of rock stars Leon Russell, Greg Allman, and J. J. Cale. Song after song (including the future Captain and Tennille mega-hit “Muskrat Love”) was coy, melodic, brilliant. But the second album failed to materialize, and Ramsey moved to Nashville as the Austin scene began to fade. He eventually wound up in Scotland, where he spent several years living in a lighthouse. “Willis taught me so much,” Lovett tells me. “Listening to his record showed me that you don’t have to play straight-ahead blues to have blues be a part of your music. He’s so soulful.”

“What do you mean? How did he teach you?”

“Well, just with his vocal style. He’s not playing the shuffle kind of stuff you hear in a bar on Sixth Street in Austin. He does it with narrative that’s not restricted to the sixteen-bar blues form.

“Willis and I have gotten really close,” Lovett continues. “I talk to him all the time now. But I didn’t really know him until he came back to Nashville from Scotland. I’d see him at Walter Hyatt’s house. I played ‘Sleepwalking’ a couple of years ago when I was touring. The crowds always loved it, laughed at the right spots. He’s got a bunch of good new songs.”

“So there’s going to be a second album?”

Lovett grins again and delicately pours more coffee. “Willis is a perfectionist. Everything’s got to be just right.”

BY 1983 LOVETT HAD TWO DEGREES from A&M—journalism and German. He has said he stayed in school for six years because it was easier to tell people he was a student than a little-known musician. “I was playing the same half-dozen clubs in Texas,” he says. “I’d come to realize I didn’t know anything about the business of music. I was in Luxembourg that September, playing an American-music tent at a fair, and met some musicians, Billy Williams and his band, from Phoenix. I’d never recorded with a band before and was curious what that would sound like. When I got back, they helped me make a demo tape, and in ’84 I went to Nashville.”

Lovett was not lacking in confidence. He went straight to the offices of the American Society of Composers and Publishers, a performing rights organization that represents songwriters, and left a tape. A membership representative was soon making calls and setting up appointments for him with publishers. Lovett left another copy of the tape with a brief note at the publishing company of Guy Clark, who had made a deep imprint on the Texas scene of the seventies with “L.A. Freeway” and other songs.

“I finally got around to listening to it, and it flipped me smooth out,” Clark says. “I was making everybody listen to it. I was just obsessed. Then one day I was walking through a restaurant and saw a friend, an Irish guitar player. He introduced me to this guy he was sitting with. I took one look at him and pegged him for a French blues singer. I went on and sat down and then finally lights and bells went off. That was the guy who left me all those incredible songs.”

Within a year, Lovett had publishing and recording deals. His first album, Lyle Lovett (1986), was the demo tape he had recorded in Arizona, dressed up with overdubbed vocals by Vince Gill and Rosanne Cash. Willie Nelson eventually covered two memorable songs from the record, “Farther Down the Line” and “If I Were the Man You Wanted.” In New York several years later, at a songwriters forum at the Bottom Line, Lovett once again jolted Guy Clark. “I was up there with John Hiatt, Joe Ely, and Lyle,” Clark says. “The moderator asked us all to play a song we wished we’d written. Lyle was two verses into his before the shock came to me what he was singing. ‘Step Inside This House’ was literally the first song I ever wrote. I’d put it on a couple of rough demos, but how did that ever get to him?”

Through the osmosis by which popular music moves and thrives: Lovett had learned it from songwriter Eric Taylor.

LOVETT’S DEBUT WAS A MOSTLY COUNTRY album, though he showed his willingness to stretch the form with “An Acceptable Level of Ecstacy (The Wedding Song),” an edgy glide through a big-band bash at Houston’s Warwick Hotel. Ever since, he has broadcast his eclectic songwriter’s schooling and put distance between himself and Nashville—with quirky humor, surreal story lines, and exotic arrangements. Even when his music sounded vaguely country, he couldn’t resist poking fun at the genre, composing songs such as “Creeps Like Me.” What country deejay was going to put that on the playlist?

In 1989 Lovett invoked shades of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw with Lyle Lovett and His Large Band, a supremely confident, deadpan smash. Behind all the tuxedos and brass, he showcased some of the best he had heard in Texas. Lovett used to open for Walter Hyatt, David Ball, and Champ Hood when they came together in the inventive, jazzy acoustic trio Uncle Walt’s Band—an act first championed by Willis Alan Ramsey. Now Lovett brought them back for a one-time reunion (they had broken up in 1983) in the record’s harmonic, doo-wah closer, “Once Is Enough.”

Lovett’s album sales reached a high mark with the 1992 release of Joshua Judges Ruth. Again he extended the lessons of his teachers. Michael Murphey and other songwriters of the seventies lifted lyrics and strains from hymnals; Lovett added to his band a black gospel group that sounded as if it came wailing out of Houston’s Fifth Ward. The ties that bound Joshua Judges Ruth were going to church and funerals. “Now my second cousin / His name was Callaway / He died when he’d barely turned two / It was peanut butter and jelly that did it / The help she didn’t know what to do / She just stood there and she watched him turn blue.”

Half a million to a million albums sold is paltry commerce in some quarters of the music industry, but the revenue Lovett generates is sufficient that his record company lets him do whatever he wants. He has a loyal base of fans who have a high opinion of their intelligence and believe they hear it echoed in his music. When did Lovett stop being merely a singer and songwriter and become an icon of the cool? Probably when the movies, the ultimate in American celebrity, came to him.

Director Robert Altman saw Lovett play a concert, called him, and asked if he was interested in acting. He was. Lovett fared well in small parts as a detective in Altman’s The Player (1992) and a baker in his Short Cuts (1993). Like Willie Nelson before him, Lovett was put onscreen essentially to play himself. During that period, he recorded “Creeps Like Me,” and while that is not exactly how Altman has typecast him, the director clearly sees in Lovett’s face and mannerisms an intriguing oddball. (Another Altman movie featuring Lovett, titled Cookie’s Fortune, is set for release next year.) Reaction to Lovett’s recent performance in a larger role as a straight-arrow sheriff in director Don Roos’s The Opposite of Sex has been mixed, to put it mildly, but he’s not in the market for a career change. Music is still his meat and potatoes; acting is just gravy.

Sometime during his early romance with Hollywood, Lovett began his romance with Julia Roberts, forever solidifying his reputation as a ladies man—however shy and awkward. He played this role with his usual sly charm on a 1992 Austin City Limits. Stammering and cutting his eyes, he regaled the crowd with a lead-in routine: “I’d like to make a special dedication to anyone in the audience this evening who’s ever been involved in a romantic relationship of any kind.”

He clung to his guitar and squinted as the crowd tittered.

“And, and . . . who may have had that relationship not work out quite the way you’d hoped it would.”

More hoots as he ducked his head and squirmed.

“And, and . . . who may have tried to console himself or herself by rationalizing that the person who maybe initiated the breakup of the relationship would one day live to regret it.”

The song was called “She’s Leaving Me Because She Really Wants To.”

IT WAS DUSK WHEN WE STARTED TALKING, and now the sky outside the New York hotel is the hue of eggplant. I pick up the tape recorder to see if it’s still rolling and can’t tell. I can barely see the legal pad I’m writing on. The room is dark when Lovett jerks his chin, rises slowly from his chair, and turns on the lights.

We had been talking about the craft of songwriting. “There was a folk music scene in Houston in the late sixties,” he continues. “Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, and Jerry Jeff Walker were all living there. I never got to see any of that, but when I came along, I’d be playing clubs there and hear the stories. Those guys had an artistic approach to songwriting. They didn’t talk about what buttons you had to punch to get a song on the radio. They talked about the merits of the song.”

Lovett’s close friend Walter Hyatt, one of the best-liked Austin musicians of the seventies, died in the ValueJet crash in the Florida Everglades two years ago. Then last year Townes Van Zandt succumbed to his demons and vices. “I’d been thinking,” he says, “about making this record for a while, and that helped me decide not to wait any longer. I had to set parameters for myself because there were so many possibilities. It was not my intention to represent Texas singer-songwriters—the whole scope of Texas music—in an academic way. That’s impossible. I decided to stick to songs that were really a part of my life. Starting with the ones I played in that restaurant on Farm-to-Market 1960 when I was eighteen years old.”

That said, it’s almost as if Lovett went out of his way on Step Inside This House to help the heirs of Hyatt and Van Zandt; each songwriter has four songs on the album. At first, the cuts I found myself playing over and over were Ramsey’s “Sleepwalking” and Fromholz’s droll “Bears.” But the one that grew on each hearing is a moody and complex love song called “Ballad of the Snow Leopard and the Tanqueray Cowboy,” written by musician and former practicing Austin lawyer David Rodriguez, a man who now lives in Holland. Rodriguez’s lyrics and melody carry Lovett about as far as he’s gone as a singer. Michael Murphey’s “West Texas Highway” stirs memories of his cosmic cowboy heyday in Austin. “Rollin’ By,” by Robert Earl Keen—Lovett’s friend from those days in what was then, musically, an Aggie backwater—explores the same theme with more drama and power. Most of the honky-tonking is old-fashioned and muted; the tracks seldom add more than a clean blending of mandolin, Dobro, cello, and guitar. Lovett wants you to hear the writers’ lines and what his lolling tenor voice brings to them.

“Not all of these songwriters got the recognition they deserve,” Lovett muses, “but in a way their work translated into an enduring part of mainstream music. Austin music in the seventies was about freedom and rebellion, and that wasn’t just happening in Texas. It was closely related to Southern rock. Now Southern rock comes packaged as mainstream country.”

“That’s right,” I say with a smile, thinking of all the loud, overproduced pap blaring forth now from kicker stations. “Nashville country is the genuine redneck rock.”

WE’VE FINISHED THE COFFEE AND talked until I’m no longer taking notes. “I can’t separate my reaction to your record from my affection for that time in my life,” I tell him. “What about people in your audience who’ve never heard of this material or these guys?”

“I can’t believe that people who like my music aren’t going to love these songs. For one thing, I’ve been performing them all along. At a party somebody hands me a guitar. I don’t want to sing one of my songs, so I sing one of these. They listen to it. They respond.”

“Was it hard to decide on the list?”

“Not really. I didn’t have to learn one new song. But it did force me to look twice as hard at myself as a singer.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, it’s really different from recording your own stuff. It’s a different responsibility. You want to respect the original version and the songwriter’s intent, and at the same time not do a straight cover. Recording your own song, you can chalk off a lot to personal interpretation—kind of make it up as you go along. But when you’re doing something that already exists, lots of people know how it goes, and you’ve got to get it right.”

Lovett rides down the elevator with me and says good-bye in the lobby. He has other appointments that will no doubt carry him deep into the pleasures of the New York night. As I watch him walk off, I think how success has changed him—it’s made him about as cosmopolitan as they come. But I also think how some things never change, like knowing a good song when you hear it. And knowing how to sing it.