As he has done hundreds of times in his 33 years, Ho Ngoc Thanh bows his head to hear the words of the Holy Mass. There is a reading from the Book of Isaiah:

Thus says the Lord:

Remember not the things of the past, the things of long ago consider not;

See, I am doing something new!

Now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?

In the desert I make a way, in the wasteland rivers. . .

Your sins I remember no more.

Port Arthur, Texas, is neither desert nor wasteland, but alone among the twelve Vietnamese men sitting together in a middle pew at St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church, Thanh grasps the appropriateness of the text to their situation. The rest cannot understand it. All of them are refugees who have been in the United States less than a year, much of that among their displaced countrymen at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas; English is still as alien to them as the modern glass and brick lines of the church. Only the ritual of the Mass is familiar. Like most of the more than 1200 Vietnamese (the figure rises weekly) who have been resettled in this unlikeliest of places, the self-designated “Golden Triangle” of Southeast Texas, the men are Catholics.

Thanh himself has special reasons for contemplating the words of Isaiah. He arrived in Port Arthur only the evening before, and after nearly a year of confusion and wandering he hopes to make a home there. For Thanh and his friend Hoang are typical of a growing number of Vietnamese refugees whom the United States government has not so much resettled as simply scattered across the countryside. With no jobs, no sponsor, and no permanent place to live, Thanh and Hoang have chosen Port Arthur because five members of the helicopter crew that Thanh commanded and flew to refuge with the U.S. Seventh Fleet in the South China Sea are there and doing well.

Ironically, it was Thanh’s adequate English and his relative preparedness for American life which set him adrift to begin with. Eager to escape Fort Chaffee and already familiar with what he would find outside its fences (he had been flight trained at San Antonio’s Kelly Air Force Base), Thanh had accepted an early sponsorship offer from a policeman in a small town outside Springfield, Missouri. There he and Hoang had found themselves offered food and shelter on an isolated dairy farm in the Ozarks, but no pay for their work. Faced with what was to them a bitterly cold winter that repeatedly made their children sick and a sponsorship very nearly resembling slavery, they invested the last of what little they had brought from Viet Nam in bus tickets to San Antonio. Unable to find jobs there, Thanh and Hoang decided to join their friends in Port Arthur.

It is all too familiar a story. Hundreds, even thousands, of Thanhs and Hoangs are already in the Beaumont- Port Arthur area or are on their way. The Vietexans resettlement program sponsored by the United States Catholic Conference through the diocese of Beaumont is one of the largest and certainly one of the most successful in the country—yet its very success may prove its undoing. Precisely because it has worked so well, the resettlement program here is in danger of being overwhelmed by large numbers of refugees who have twice been victimized by this country’s uncertain Viet Nam policy— once in Asia, once in America. The government that brought them here doesn’t quite know what to do with them. It never had a cohesive resettlement program, only a vague hope that the refugees would disappear from sight and mind into the vast maw of America. To the extent that there is now an official policy, it is to discourage large concentrations of Vietnamese that will inevitably burden communities like Beaumont-Port Arthur with enduring difficulties residents never foresaw when they set out to help the homeless; yet that is exactly what’s happening. Having discovered that they can expect little from the government that brought them here, more and more refugees are gathering together with their countrymen. This movement has gained the support of many Vietnamese intellectuals and religious leaders, who regarded the original resettlement policy, with its attempts to minimize the impact of refugees on individual communities, as a cultural death warrant. Now as before they are indisposed to taking American advice about what is good for them.

Americans are adding to the influx by sending their problem cases to Beaumont-Port Arthur. One group of 30 refugees from Sacramento was put on a bus by an apartment manager who had sponsored them only so long as he could draw from their resettlement allowances to pay their rents. The local Catholic Conference was informed by telephone that the refugees would be arriving in 36 hours, but two days later there was still no sign of them. A local priest began making long distance calls to bus stations along the Greyhound route, until finally he located them in El Paso. They were in the parking lot of the bus station, having waited patiently for about 24 hours to be driven somewhere. A driver had gone off duty and no one had replaced him, and since none of the Vietnamese spoke a word of English or had any idea where they were, the refugees simply stayed put. They were accustomed to being hauled around the country for no ostensible reason; it was just one more thing that didn’t make sense.

How the refugees came to settle in Beaumont-Port Arthur is more the story of a small group of intensely motivated individuals than of a grass-roots community response; the truth is that as a community the citizens of Southeast Texas responded to the initial calls for sponsorship about like the rest of us—with general indifference, forgetfulness, or simply the feeling that it was the government’s problem to solve. The three persons most responsible for the success and the size of the local settlement of Vietnamese—there are more refugees in Jefferson County than in entire states like North Carolina, New Jersey, or Massachusetts—are Dow Wynn, port director of the city of Port Arthur and lay chairman of the Vietexans resettlement program. Father William Manger, a Beaumont parish priest, and Father Tran Van Khoat (pronounced Kwat), who first envisioned a large-scale Vietnamese community on the upper Gulf Coast. They have received little help from either the federal government or traditional relief organizations like the Red Cross, and next to nothing from the state of Texas. From the first it has been a freelance, ad hoc effort, made all the more difficult by the type of refugees they were dealing with.

For the most part the Vietnamese in Southeast Texas are part of the so-called “third wave.” No one expected or planned for their arrival; they were neither politicians nor officers nor influential civilians. Most of the men were fishermen, farmers, small tradesmen, retail clerks, policemen, or ordinary soldiers who were bewildered by the sudden and spectacular collapse of the Saigon regime. Many never intended to leave Viet Nam permanently; few of them speak English and many of the rest are making no effort to learn. It was this third wave which prompted John Eisenhower’s gloomy prediction, after a tour of the resettlement camps in April 1975, that many would have to remain in camps for the rest of their lives. A similar group of refugees which entered France after that country’s disaster at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 are still occupying refugee camps there.

Ideally, the State Department had planned to evacuate only American “clients,” who would have been primarily English-speaking Vietnamese with a chance of making it in this country. Individual sponsors would ease their assimilation into American society. Instead, in the words of a Senate report, “. . . the whole process of defining categories, ceilings, and the like was little more than a charade . . . half the Vietnamese we intended to get out did not get out, and half who did get out, should not have.” Their arrival in this country was greeted by large-scale indifference; most Americans wanted nothing so much as to forget the war and everything connected with it. The special task force managing the resettlement ran into a shortage of willing and qualified sponsors. Nevertheless, the four camps at Fort Chaffee, Camp Pendleton, California, Elgin Air Force Base, Florida, and Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, were closed in seven months. By comparison, back in 1956 when political lines were clearer, it took the same length of time to resettle only 32,000 Hungarians (less than one-fourth the number of Vietnamese refugees) from Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. Although the 300,000 Cubans who left that country after Castro’s victory arrived over a period of several years, the Senate report notes that at the rate they were handled, it would take fourteen years to account for all of the Vietnamese. And those were Westerners, all of them willing and highly motivated political refugees, many familiar with our language and culture.

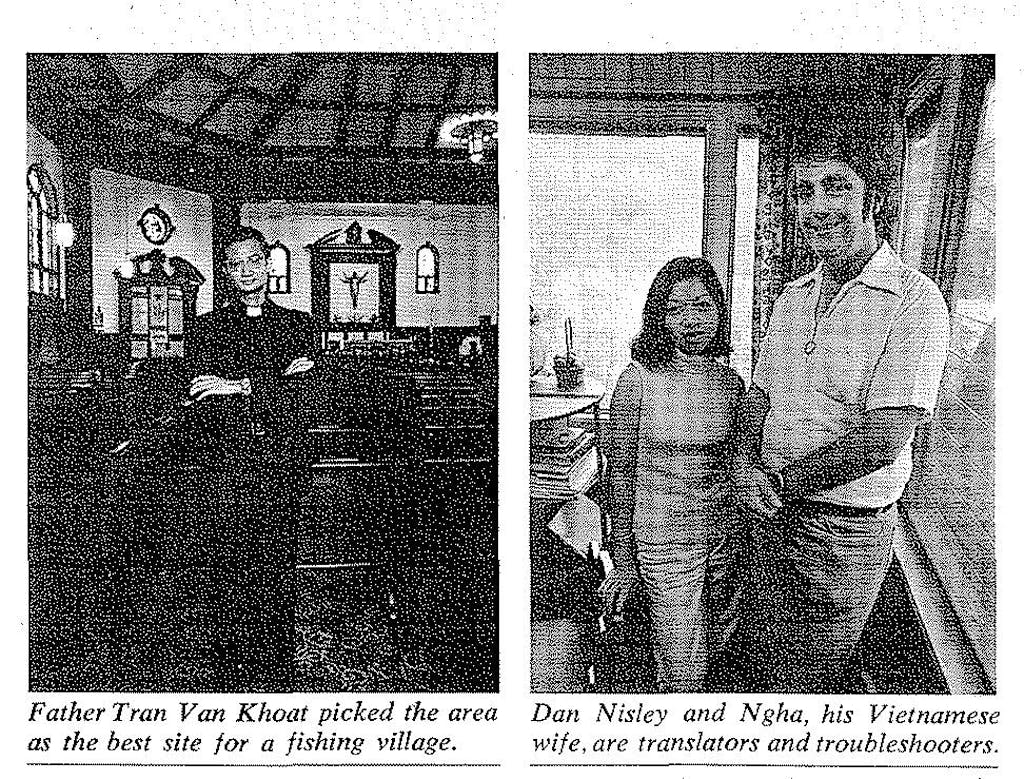

But why Beaumont? Why Port Arthur? The surprising answer is that the greatest concentration of refugees in the country (as a percentage of the local population) is no accident. While he was still at Fort Chaffee, Father Khoat envisioned a self-supporting Vietnamese farming, fishing, and manufacturing community with its own schools, hospitals, and governmental structure. His first choice for a site was Florida, where the climate and geography are similar to coastal South Viet Nam, but land on or near the water is far too expensive for what he had in mind. Meanwhile, Father Manger had been asked by his Bishop to direct the local efforts of the Catholic Conference, by far the busiest of the nine voluntary agencies that contracted with the U.S. government to handle the resettlement program. When he got involved, Manger had no idea how large the project would grow—but he didn’t know Khoat then. The two met at Fort Chaffee, and the idea of a Vietnamese fishing village appealed not only to Father Manger, but also to lay leader Dow Wynn, who saw a perfect marriage of the hard-working, industrious Vietnamese with local capital and entrepreneurial skill.

Somehow, Khoat, formerly of Da Lat, had managed to install himself as the spokesman for a group of over 150 families, many of them fishermen from the area around Vung Tau, a coastal resort not far from Saigon. How Khoat, an almost frail and boyish-looking man of 37, came to lead the group, many of whom he says are distant relatives, is not exactly clear, although he is said to be an orator of some skill. A story which he may have initiated himself, and which in any case he has done little to deny, casts him in the role of a parish priest who led his entire village to safety by sea—a dramatic vignette which, appealing as it is, has the disadvantage of never having happened. In fact Da Lat, where Khoat came from, is nowhere near either Vung Tau or the sea. Many of the refugees upon whose behalf he led noisy demonstrations at Fort Chaffee had never met him before they got to Arkansas. But that he is their leader has not been questioned.

It was the idea of the village which led Manger and Wynn to commit themselves to sponsor refugees in numbers far exceeding the willing sponsors they had on hand and the failure of which put them, as Manger puts it, “in the halfway house business.” Despite Father Manger’s observation that “if every Catholic parish in the United States had sponsored just one family there would be no problem,” it was quickly evident that nothing so visionary as that was going to happen either here or anywhere else. When they first began, Wynn and Manger sent a letter to every church (Catholic and otherwise), every city and county government, and every service organization in the diocese, which covers a large chunk of East Texas. “Not a damn thing happened,” Wynn says. “The church as an institution—all the churches—have done a lousy job. It was us, Father Manger and three or four couples who made it happen. There was no rhyme or reason, we didn’t have the time and none of us have much money. We just flat did it.”

To the extent that resettlement has been successful in Beaumont-Port Arthur, the credit belongs to individuals. Most churches and the better-known private charities did little at first to live up to their stated goals. The local Red Cross, faced at one point with several hundred homeless and generally destitute persons, offered to lend the Catholic Conference 30 blankets. Because they were afraid of losing them and having to dip into their meager funds, resettlement workers refused the offer. By contrast Dan Nisley, the Port Arthur director of Goodwill Industries, and a Viet Nam veteran married to a Vietnamese woman, sponsored her two brothers and spent countless hours serving as a translator, interpreter, and general intermediary. Wynn’s view of the failure of the organized churches in the area is shared by most of those who are active in the movement. One woman (not a Catholic) repeatedly failed to interest her church, one of the largest and wealthiest in Port Arthur, in sponsoring refugees; the experience left her embittered about attending services with “such a band of hypocrites.”

Although the initial village proposal gotten together by Dow Wynn and Father Khoat reached the detailed planning and accounting stage, it was probably doomed from the start. Not only did the village arouse a good deal of hostility and a certain amount of fear in the Gulf Coast community of Sabine Pass near the proposed location, but also the very idea ran afoul of government policy to avoid such clustering. “Experience has shown,” says Donald MacDonald, the State Department man in charge of Fort Chaffee, “that it is possible to deliver foreign refugees directly into American society, and that neither ghettoization nor the Indian reservation approach has worked very well in the past.” The first person to propose the village concept publicly was former Vice President Ky, which gave it a bad image from the start and caused many observers to dismiss it as a pretext for gathering coolie labor. Early experience had also shown the rate of sponsorship “breakdown” to be highest among commercial sponsorships, not a few of which turned out to be naked exploitation of the kind encountered by Thanh and Hoang, but on a larger scale. Whatever, a hoped-for government loan guarantee in the vicinity of $1 million was not approved.

Rather than reneging upon commitments already-made to refugees, Father Manger and his assistant Ron Rivenbark decided to set up temporary barracks-style housing in St. Anthony’s school, a decaying three-story brick building adjacent to the grounds of St. Anthony’s Cathedral in downtown Beaumont. Never intended for a dwelling, St. Anthony’s had been unused for ten years and was, to be blunt about it, in frightful condition. At its peak of operation in November, when 280 persons were housed there, conditions were far worse than they had been at Fort Chaffee. Bunk beds were jammed so close together in the dormitory rooms that passage was difficult. Had fire and health inspectors not tacitly looked the other way, it is doubtful whether St. Anthony’s would have been allowed to house anyone at all. A flu epidemic might have been disastrous.

Still, morale was reasonably high. The Vietnamese were by this time accustomed to being displaced; and as a generally gregarious, disciplined, and very patient people to begin with, they were able to adapt to the total lack of privacy and organized diversions far better than one imagines a group of Americans doing under parallel circumstances. Then too, visible progress was being made as day after day families found sponsors, jobs, and housing and moved out. By mid-March, St. Anthony’s was closed up for good.

Persons who are active in the operations of charitable and relief organizations generally find that the most help comes from people who can least afford it. Perhaps one has to know what real trouble is, to take it seriously.

Persons who are active in the operations of charitable and relief organizations generally find that the most help comes from people who can least afford it. Perhaps one has to know what real trouble is, to take it seriously. Repeated demonstrations of the principle are nevertheless often hard to swallow. While televised and newspaper appeals brought numerous small donations and telephone calls offering assistance to St. Anthony’s (along with a number of obscene and crank calls), the response from Beaumont’s more fortunate classes was less than hearty. Although several nurses volunteered their time to staff a small clinic set up to deal with minor health problems, it was not possible to find a single physician, intern, or resident who would so much as enter the building. When several children came down with what looked to Ron Rivenbark like chickenpox and pinkeye, both diseases that could have spread rapidly in the cramped conditions at the school, he took them to the only place he could think of in town, a city-run VD clinic. (The nearest care available to patients who cannot pay is in Galveston, over an hour’s drive away.) The physician on duty refused on procedural grounds even to look at the children, although Rivenbark had a promise from the nuns at St. Elizabeth Hospital for free medicine if only he could produce a prescription. Rivenbark went so far as to volunteer to sign an official form affirming that the children, six and eight years old, had the clap, but to no avail. He drove to Galveston, where his amateur’s diagnosis was confirmed.

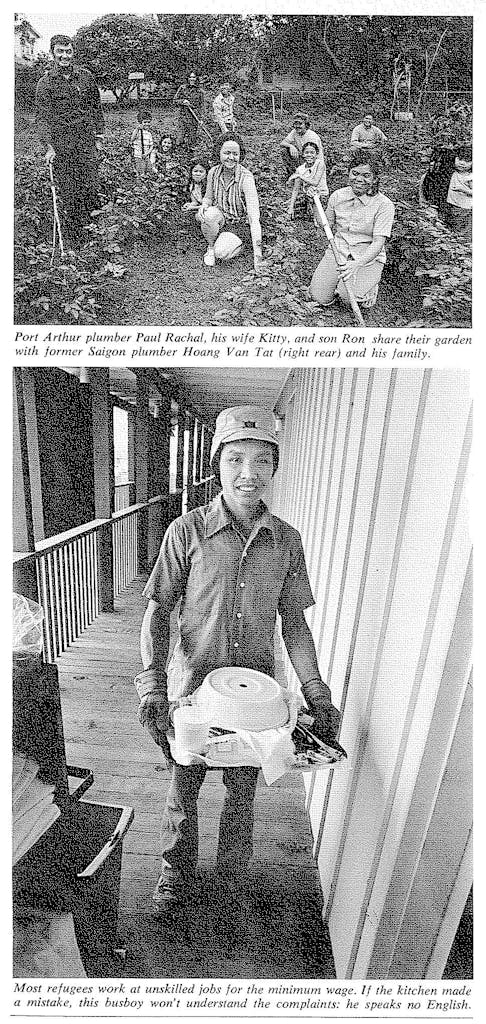

Perhaps no one incident tells more about the public indifference and the individual decency and generosity that have characterized the effort here so much as that of Paul and Kitty Rachal and the nine-member family of Mr. Hoang Van Tat. When an unseasonal cold wave pushed into Beaumont last November it found St. Anthony’s without heat of any kind. After a televised appeal for help from Father Manger (the local media have been very helpful all along), the First Baptist Church donated a scrapped but still workable gas space heater big enough to heat the entire first floor and warm the upstairs to a bearable level. But proper installation required special help, and ENTEX, the local gas utility, just couldn’t find a way to fit the work in. An ENTEX representative told Rivenbark he didn’t give a damn what happened to the people in the school building and his supervisor agreed. So Father Manger called upon Rachal, a plumber who he says has done $4000 to $5000 worth of work for refugees while submitting one bill for $45 to him. Rachal got the heater going in short order, but because of the gas company’s uncooperativeness he had to use somewhat unorthodox methods, venting it to draw air from inside the building for combustion, which is strictly against regulations. “It was safe enough,” he says. “There were so many holes and broken windows in that place there was no way it was going to run out of fresh air.” As they worked, Rachal and his son Ron, a former Seabee with Viet Nam experience, found themselves shadowed by a Mr. Tat. At first Tat said nothing and simply watched. However, when he saw Ron preparing to run a gas line through a wall in a manner that he considered less than professional, Tat interrupted, pointing and using his very limited English to convey his objections. Tat had been a plumber in Saigon and his opinions were well grounded. After telling his wife about the conditions inside the building that night, Rachal brought her to St. Anthony’s to see them firsthand and to meet the Tat family, which had just found itself a sponsor.

The Tats are now installed in a small rent house Rachal owns next to his home in Beaumont. Tat and his eldest son are working for Rachal and studying to earn Texas master plumber certificates, which would enable them to make a good living on their own. The families are jointly cultivating a large vegetable garden in the yards behind the houses. Above all, Rachal wants to prevent the Tat family from accepting public aid, which he thinks makes economic invalids of its recipients. “When things get slow I tell them to hang in there, we’ll survive. If it gets so bad we have to go on welfare or food stamps then we’ll all go on stamps together.” Among the motives of persons who have been willing to turn their lives inside out for the Vietnamese, political considerations are notable for their absence. Dow and Audrey Wynn are a case in point. Like most Americans, the Wynns agonized over Viet Nam, and while they are reluctant to discuss the exact shading of their opinions then, one gets the impression that like so many others they began by supporting the war effort out of patriotic and religious conviction and became progressively more confused. Asked what the majority of the sponsors thought about the war, Audrey seems genuinely surprised. “I can’t say. We haven’t discussed it. Isn’t that strange,” she says, half to herself, “that we never discussed it?” Their decision to become involved in the resettlement program came rather as a direct result of their participation in the Charismatic movement of the Catholic Church, and more specifically the “Love and Peace Community” at St. Peter’s. “Without it,” Audrey says, “a few years ago, we would not have involved ourselves. We believed it would be an effective way to make a Christian witness.”

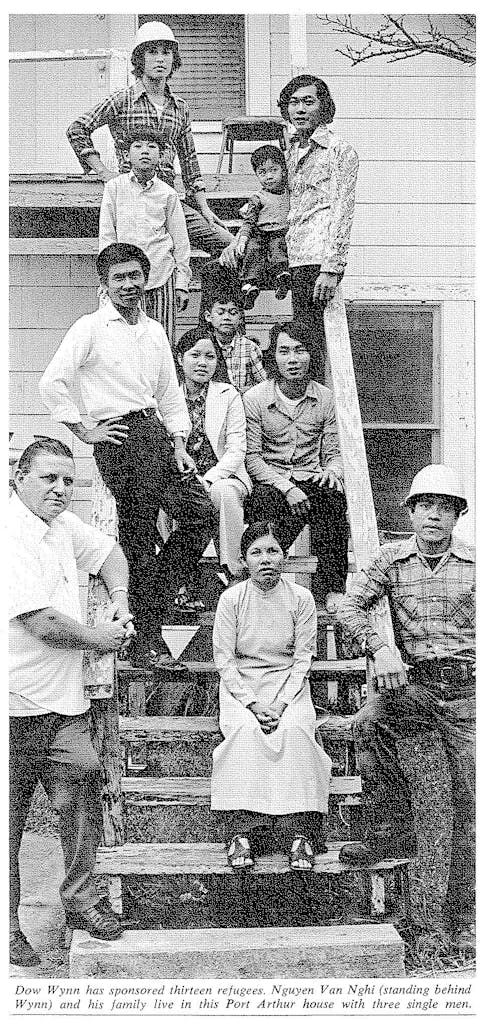

Besides countless hours of time, energy, and know-how (Wynn is said to know every employer of consequence in the region), the Wynns have sponsored thirteen refugees. Eight are in the family of Nguyen Van Nghi, a 40-year-old former fishnet mender from Vung Tau who now works for a moving and storage company. Mr. Nghi, who lost one eye in a childhood accident, has a cataract in the other and is slowly losing his vision, an affliction which concerns him less at the moment than the seasonal nature of his employment and his limitation to 40 hours a week in the busy times. Even with Nghi and eldest son Hy, 17, working fulltime at the minimum wage ($2.30 per hour) there is not much money for a family of eight, and, since they speak very little English, not much to do in their spare time. So they and three Vietnamese men, who share the second floor of the modest and sparsely furnished frame house in a pleasant, racially mixed lower-middle-income neighborhood, have begun a large vegetable garden on a vacant lot next to their house. They hope to grow most of their food there, since, like most Vietnamese, they eat little meat. Dow has persuaded a Houston eye surgeon to operate on Nghi’s eye in Galveston later this year. If the operation, to be paid under Medicaid, is successful, the family’s future would be relatively assured.

A language teacher’s eyes would roll back in his head to hear Dow addressing the Nghis in the kind of pidgin English used by TV Indians, but when he says, “You get check. Sign name. Give me. Me put in bank. Bank keep for you, no steal,” the checks are produced, endorsed, and handed over with affectionate smiles all around.

Not all the refugees are so fortunate as the Nghis. Many are still war-scarred and fearful of strangers, particularly Americans. Some are reluctant to trust their sponsors or anyone else with personal or financial matters and conceal what little English they may know from persons trying to help them. Since they don’t speak English, most refugees have no telephone, cannot get a driver’s license, and have few sources of entertainment. Many of the older Vietnamese are living lives of extreme isolation; they rarely venture out-of-doors. For some the nearly ubiquitous black-and-white used TV sets their sponsors have given them are their most regular link with the outside world—and even then they understand little more than the pictures. One man in Port Arthur, reluctant to confess that he was hungry, took to trapping and eating rats, a practice not unheard of in Viet Nam, where cats and dogs are sometimes eaten as well. It was not until a worm infestation gave him severe gastric problems that anyone discovered what he had been up to. But at least here the refugees can help each other in their adjustment to new lives. The Catholic Conference sees that each family is visited regularly and has arranged numerous social gatherings on religious holidays. Cultural and physical isolation on a chicken farm in Center, 32 miles east of Nacogdoches near the Louisiana border, caused two Vietnamese families to move back to Beaumont with relatives; 32 persons now share a small two-story frame house.

“They are a blessing. These people are going to weave a whole new thread of gold through America.”

The Wynns’ five “sons,” Tu, Hieu, Dang, Kinh, and Gia, who range in age from 21 to 28, live together in a small apartment and share expenses, like most of the other Vietnamese single men here. Living as frugally as they can, most of them are able to bank over half of their take-home pay of less than $3 per hour. Still, time weighs even more heavily on their hands. Single men were among the group considered at Fort Chaffee to be the most difficult to resettle. With no family to help cushion the emotional blows, they are more susceptible to the feelings of anomie and cultural deprivation that affect all of the refugees; at the same time that their situation virtually demands that they adjust even more fully to American life than the others. Unlike some of the adults with families (particularly the older ones) who refuse to learn English, they must. It is a matter not only of physical but also of psychic survival. Until then the Wynns, whom the men call “Ma and Pa,” are trying to fill a very large gap in their lives. “They’re just our children,” Dow says. “All they have known is war,” Audrey adds, “and yet they are unwarlike. They have a very peaceful nature, almost no aggressiveness. They should be bitter and sour and aren’t, compared to our American children.” Later on, Dow adds, “They are a blessing. These people are going to weave a whole new thread of gold through America. I just wish we could have this kind of relationship with our four kids.”

Not all of the sponsors feel so paternal about it. Father Robert J. Mulligan, a Bronx Irishman who is pastor of St. Therese’s parish in Orange, a Sabine River community about 30 miles east of Beaumont, is blunt-spoken on the subject. “Our attitude here,” he says, “was get them a job, get them a home, and cut the strings. I tell them, ‘The Great White Father died. You better learn to take care of yourself.’ You can’t protect them from life. They’re going to get robbed and cheated just like you and me.” Mulligan, who was stricken three years ago by Hodgkin’s disease and told he had only months to live, found his commitment to help the unfortunate strengthened when the disease went into remission. “If God could do that much for me,” he says, “this was the least I could do.” Still, he does not think that sponsors who smother the refugees with attention, once they have jobs and housing, are doing them a favor in the long run.

What Mulligan and his parishioners have done is doubly interesting in view of the fact that he is a member of the Josephite Fathers, an order dedicated to work among black Americans, and St. Therese’s congregation is mostly black. Although it has sponsored far more refugees (144) than any other church in the area (and perhaps in the United States), it is, as one would expect of a small black parish in East Texas, not a wealthy one. In as many cases as he could, Mulligan used the $300-per-person resettlement allowance that was credited to each refugee by Congress to make down payments on houses. As an official sponsor of one twelve-member family, Mulligan got $3600 from the government and with that and a $600 bank note, he put them in a modest home in a predominantly black neighborhood in Orange—a home they will own by February. He has done the same for nine other families, averaging ten members each, and tries to convince others to follow their example. Home ownership, he believes, will insure permanence and stability. Every one of the families St. Therese’s has sponsored has at least one member working full-time and some have as many as three. Father Mulligan has nothing against welfare and food stamps where needed and says that officials in both programs have gone out of their way to be helpful in Orange, but the persons he is responsible for are very nearly self-sufficient. Each person employed in Orange makes $5000 to $7000 a year and several families have two employed members. If the program were doing anywhere near that well nationwide, a large part of the refugee problem would be solved.

Despite Father Mulligan’s involvement, relations between blacks and Vietnamese show occasional signs of strain—and they are not helped by white attitudes one would expect to find in an area which politically is more like southern Louisiana than most of Texas. Many of the whites involved in the resettlement speak favorably of such Vietnamese cultural attitudes as thrift, industriousness, and strong family ties; they often make implicit and sometimes explicit comparisons between the refugees and local blacks. At least one Vietnamese in Beaumont has lost a job because of hostile attitudes of black workers, and some blacks see the refugees as possible competition for unskilled jobs. Whites tell stories of garbage bags thrown on the porch at St. Anthony’s (which has the misfortune to be located near a bawdy house in a black neighborhood), of racial insults, and harassment on the streets. Father Mulligan, however, doubts that blacks as a group are responding to the Vietnamese very differently from anyone else in America, and any feelings of economic rivalry that exist are more than counterbalanced by a shared knowledge of what it is like to be on the outside looking in. To the half-dozen of his parishioners who wrote complaining that their church was spending much more than wealthier churches. Father Mulligan answered with a rhetorical question: “I just asked them,” he says, “should we do less because they do nothing?” In any case the Vietnamese are not at the moment an economic threat to anybody, white or black. Despite high unemployment statistics, jobs at or near the minimum wage are plentiful here, as they are in most of the country. Few Americans will do dull or messy work for no more money than they can get on welfare.

Although Father Mulligan in Orange County has received help from state agencies, his experience seems to be the exception. Texas is second only to California in the number of refugees resettled here (27,000 to 10,000), but no one here can recall a single particle of practical help from the special committee appointed by Governor Dolph Briscoe to deal with refugee problems. Ron Rivenbark goes so far as to say that, although this committee was supposed to facilitate the delivery of available state services on an emergency basis, “If that’s how they treat emergencies, the Vietnamese would all be dead and buried before they got around to responding.” In Beaumont the most bothersome difficulties have been with the Department of Public Welfare (DPW), many of whose caseworkers, Rivenbark says, are openly hostile. It has not been uncommon for the refugee, his sponsor, and an interpreter to show up at the DPW office for a scheduled appointment, to wait for hours, and to be told then that the person they had come to see was not in, or worse, to be met with an impenetrable web of red tape administered with an inflexibility that under the circumstances seems downright malicious. “We’ve had college-educated sponsors throw up their hands and come out of there crying,” Rivenbark says. “They are getting a real education. After you’ve spent the day down there, you feel like you’ve not only earned any money that you get—you’re underpaid.”

DPW officials, of course, deny all this and maintain that refugees were given inaccurate information at the resettlement camps that they would be eligible for aid for which they do not qualify under the Texas Aid to Families with Dependent Children Act. They further blame language problems and complicated paperwork, particularly in regard to the federal Medicaid program, for which large numbers of refugees seem to qualify everywhere but Texas. HEW statistics, for example, show that Pennsylvania, which has only two-thirds as many refugees as Texas, has processed 2270 persons for Medicaid, while the DPW has managed only 243. California has processed Medicaid applications at nine times—and financial assistance payments at double—the Texas rate. HEW officials in Dallas are reluctant to criticize the DPW directly, but do point out that the other states in Region Six have been willing to make adjustments that Texas has not.

No one knows any longer how many refugees are in the Beaumont-Port Arthur area. By mid-April an average of 20 to 30 new arrivals was registering each week with the Catholic Conference. Undetermined numbers have apparently decided to go it alone and are seen on the streets. Although he has managed to cope so far, Father Manger now fears that the community resources of manpower and good will are strained to their limits. “We lucked out at first with a good first-class image,” Father Manger says. “There was no doubt that they were deserving people that needed help. But we’ve reached the limit of sponsorships here. It is headed towards a ghetto.”

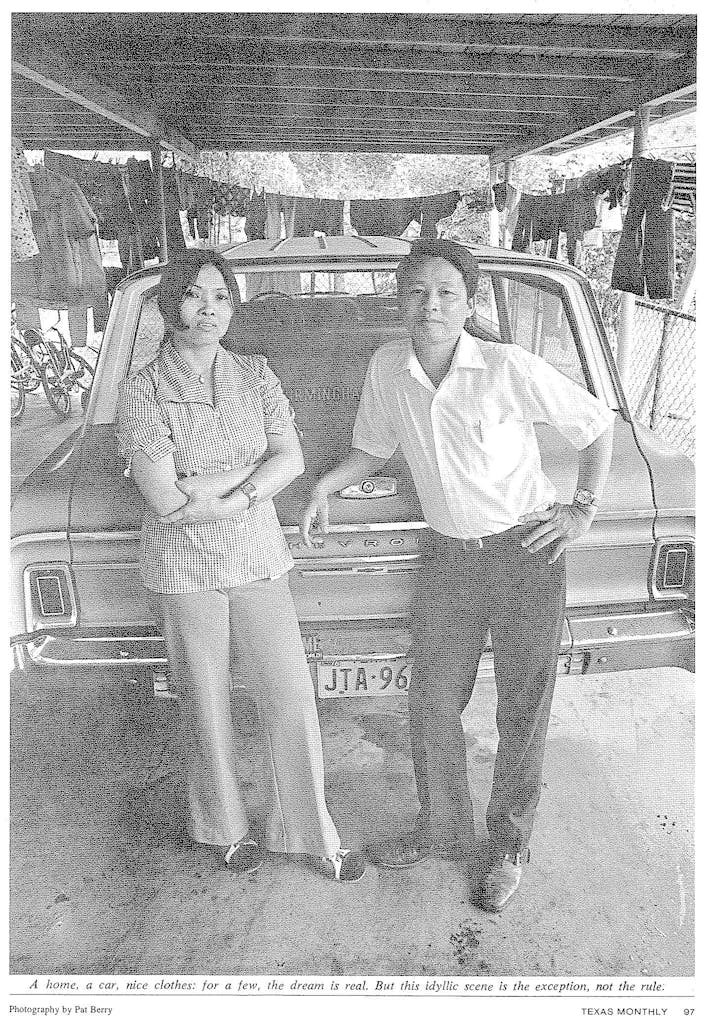

The word ghetto is one that is used often by those who are concerned with the future of the Vietnamese refugees here. Nobody thinks it is a good idea. Many think Father Khoat’s persistent efforts to reunite all the people he led at Fort Chaffee are partly to blame. Khoat has kept in touch with his people by mail, telephone, and a Vietnamese-language newsletter he edits—and, it is said, writes, signing the more innocuous pieces and employing pseudonyms for the strident ones. The newsletter is financed by donations solicited from the refugees and is devoted primarily to strong anticommunism and propagandizing for the “Vung Tau Village,” which Khoat still proposes to begin at a yet undisclosed spot near Beaumont. Khoat believes that it is the only chance most of his adult followers have to lead productive and happy lives in the United States. The children, he thinks, will be easily assimilated into American life within a generation, although he is clearly a cultural nationalist who one suspects is less happy at that prospect than he will say to American visitors. For their parents he sees only sadness unless he is able to have his way, drawing distinctions between American and Vietnamese society that are sharpened by his shaky English: “Americans are happy when they are comfortable. They prefer to live alone as long as they have a big house, a car, television, washing machine, and so on. My people need a community to live with and enjoy one another, to share happiness, sadness, and joy in our own way. When they live alone, they are unhappy.” In a recent newsletter Father Khoat claims to have about 1000 acres of farmland in a vaguely described location somewhere between Beaumont and Orange on the Sabine River, although when I spoke to him just before the announcement he could not remember where the tract under consideration was. He said he had also raised the capital and would soon be buying his first fishing boat and preparing to set up a factory to manufacture fish sauce. His investors, whom he would not name, are said to be businessmen from New York, Washington, and California. Because it is a violation of Canon Law for a priest to involve himself in secular business affairs, Khoat’s name cannot appear on deeds or incorporation documents without his incurring very serious ecclesiastical difficulties. More than one observer in the area thinks that Khoat’s statements are simply untrue and are intended to serve only as a means of encouraging Vietnamese families to come to the Beaumont area, presenting to those who would discourage the influx a simple fait accompli. Others hold even less charitable interpretations of his actions. Whatever may be the truth, Khoat has in the past urged refugees to give up seemingly satisfactory sponsorships from as far away as California and Florida to come here on the pretext of jobs and housing that did not exist.

Persons who resist Khoat’s schemes for a village tend to do so quite strenuously. One of those is Goodwill Industries’ Dan Nisley, who believes that what Father Mulligan has done in Orange is a model of what should have been done everywhere. “Khoat held up dreams,” he says of the earlier discussions of the village idea, “and we held up reality. We tried our best to tell them dreams are fine, but tomorrow you have to have food.” He fears that the village, if it could be established, would become a magnet for refugees in difficulty: “a good place to throw a bunch of people we didn’t have anything good to do with.” Nevertheless, Nisley, who knows a good deal more about Vietnamese society and culture than any of the other Americans in the area, foresees serious difficulties that he believes are only beginning to surface. Despite his admiration for the selflessness of many of the American sponsors here, he emphasizes that “you can’t keep on an emotional high forever.” Many sponsors, he fears, have tended to sentimentalize the refugees’ situation and are riding for a fall to the extent that they expect the Vietnamese to respond to their kindness better than anyone else would. For one thing there is the inevitable clash of cultural values. “Like everybody else,” Nisley says, “the Vietnamese can be terribly racist. They don’t especially like us. By and large they consider themselves smarter than Americans. They believe that they have a superior culture, which is why many of the older ones will not change their ways. And as a group an awful lot of them are not grateful. Many sponsors have opened their lives to them and expected a gratitude that is not coming through. A lot of the refugees think we owe it to them. We told them we did. We told them that our actions made it necessary for them to leave their country and come here.” Whatever the reason, Nisley’s fears are beginning to come true. Dr. Nguyen Van Chau, a refugee with a doctorate in English literature from the University of Paris who works for the Catholic Conference in Port Arthur, says many of the sponsors have grown “morally tired and sometimes bitter” over personal difficulties with refugees and are relying more and more on his office for help. Like the other voluntary agencies, the Catholic Conference long ago spent its share of the funds allocated by Congress, and there is no more money in the government pipeline. But, while the lead item carried by most of the news media following HEW’s March 15 report to Congress was that almost eight of ten refugees who headed families had jobs, by simply turning that figure around one comes up with a more than 20 per cent unemployment rate, hardly sparkling. The fine print makes things even clearer: 18 per cent of refugee households are earning less than $2400 annually, another 15 per cent between $2400 and $4799, and 21 per cent more between $4800 and $7100. Given the large size of Vietnamese families it is likely that close to half of them are existing well below the poverty level.

Given their lack of job and language skills, one could hardly expect the bulk of the refugees to be doing much better after only a little more than a year in this country. But the point is that the government, which bears direct moral (and physical) responsibility for the refugees being here to begin with, is pretending that the problem is largely solved. In the words of Dale DeHaan, the staff director of the Senate Subcommittee on Refugees and Escapees, a man who has been closely involved with resettlement work for twelve years: “The President in effect evacuated these people and once they got here the federal responsibility was diluted. There should have been more follow-up but there wasn’t. The Administration’s refugee policy is like its social policy. It assumes that they can make it in America on their own because everyone else does.”

But even a casual drive around the Beaumont-Port Arthur area shows that quite a few persons there are not “making it” in the style to which most Americans would like to be accustomed. Large sections of both cities appear unchanged from the last time it was considered polite to mention widespread deprivation in American society. Perhaps that is why Dr. Chau, who says he resisted it at first, has come around to the idea of some kind of a village or community where his displaced countrymen can, as he wrote in a paper he submitted to Task Force officials late last year, “be productive and thus regain self-confidence and self-respect.” It may also be why, almost alone among the persons closely involved with the resettlement effort here who will talk about it, he understands and sympathizes with Father Khoat and believes him altogether sincere in his motivations. And when he speaks hopefully of establishing an Indo-Chinese Studies Center at Lamar University in Beaumont, one senses that Chau has in mind a larger and more coherent Vietnamese community than currently seems likely to exist here unless there is a change in the way things are being done. As a former official at the South Vietnamese government’s Revolutionary Development National Training Center at Vung Tau (which he left in 1968 when the Thieu government began to jail its leaders because it feared a “third force” developing there), Dr. Chau has not yet lost his belief that “we can motivate these people. The more ignorant they are to start with, the better . . . if you choose a good doctrine and inculcate them with that, they will be leaders.”

To that kind of thinking Dan Nisley has a simple answer: “Dr. Chau sees a ‘strategic hamlet,’ a rural village. I see the slums of Saigon.” But Nisley’s own scenario of the next few years is little better. He believes that after the sponsors tire and the churches quit, the refugees will simply begin showing up where the indigenous poor do, in welfare lines, at the Red Cross, Goodwill, the Salvation Army. Eventually, he believes, the Vietnamese refugee “problem” will disappear—not because it no longer exists, but because we have ceased to pay attention. In that, he and Dr. Chau agree. “If nothing is done,” he says, “they will completely disappear into the mass of poor Americans in five years.” Sitting in his spare office in Port Arthur’s grandiosely titled World Trade Building just down the hall from Dow Wynn’s office, Chau looks at the bulletin board with up-to-date listings of all of the refugees registered with the Catholic Conference. Included are entries like “family of twelve, breakdown from Amarillo” (a breakdown is a severance of relations between refugee and sponsor), “three young men from Michigan,” “family of seven, breakdown from California.” Then he looks down at his neatly folded hands. “I don’t know,” he says quietly, “sometimes I think we ought to let all the Vietnamese who want to come flood in here. When it becomes an issue, we will get some action.” He pauses a moment and adds, “But that would be foolish.”

But the way things are going here, it may happen anyway. At least it will if Father Tran Van Khoat has anything to do with it. We never have known how to make the Vietnamese do what we wanted them to do or known with any clarity what we wanted to do for them. And in spite of many Americans’ decency and generosity—which in Beaumont-Port Arthur has transcended all reasonable limits—it is clear that we still don’t know.

- More About:

- Beaumont