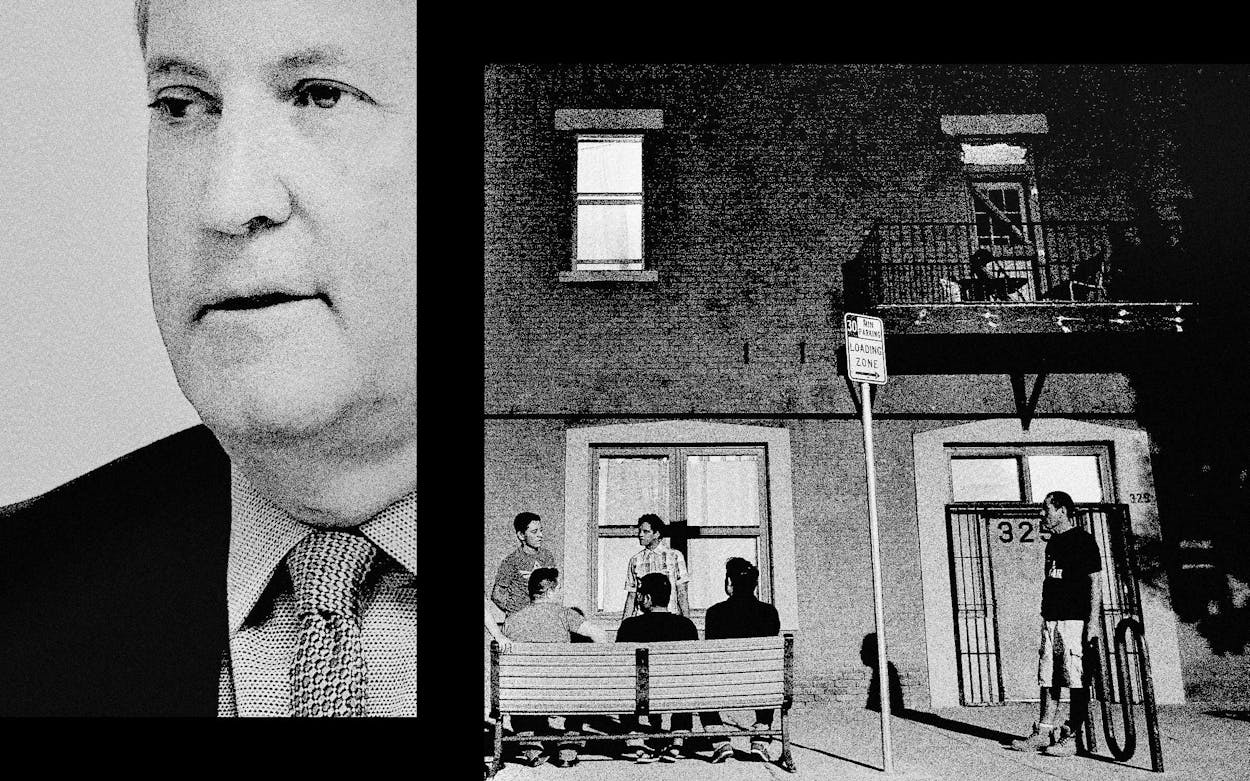

The borders of Ken Paxton’s vision of religious freedom became a little clearer this week when the attorney general sued Annunciation House, an independent Catholic immigrant ministry in El Paso. Claiming suspicions of “alien harboring, human smuggling, and operating a stash house,” on February 7 Paxton demanded the respite center’s documents regarding the identities and services rendered to the immigrants. Annunciation House asked for more time to seek counsel on whether any of the documents could legally be withheld. Paxton refused, so the migrant-aid group sued Paxton; now Paxton is suing Annunciation House to revoke its state license.

In describing Annunciation House, Paxton’s press releases use the term “nongovernmental organization” (NGO), the term used most commonly to describe international relief agencies such as those that partner with federal governments and the United Nations. This is a specific word choice. There’s no technical difference between an NGO and a nonprofit organization in the United States, but on the far right, where Paxton generates votes and campaign funds, there’s a big difference in connotation. NGOs are big, liberal, global actors. Nonprofits are the do-gooders next door, and they are often religious. The irony, of course, is that it doesn’t get much more next-door or religious than Annunciation House. Its website reads like a testimony at a Wednesday night prayer service: “the Gospel calls us all to the poor and . . . the life and presence of Jesus in the Gospels is so completely in relation to the poor.”

“From my perspective, it’s incredibly frustrating to see politicians who regularly justify their actions based on their faith to then persecute those who use the same rationale to do things they don’t like,” said Stephen Reeves, executive director of Fellowship Southwest, a missions and advocacy group affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.

Reeves spent years as a lawyer with the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, working to preserve the special place of religion in the United States. Paxton’s intentions are explicit, Reeves said, and instructive as to the kind of hostility religious organizations in Texas can expect if their expressions of religion aren’t in favor with the attorney general’s office. “It’s really trying to scare religious nonprofits into not following the dictates of their faith.”

And if Paxton will go after a Catholic organization, there’s no reason to think he won’t also target one of the many Protestant border missions, many of which Fellowship Southwest supports, that have responded to a need in a way that they felt their faith demanded. “They feel very called by their faith—by what they understand Jesus telling them to do in the world—which is to serve migrants,” Reeves said. (Paxton’s office did not respond to an interview request by the time of publication.)

Annunciation House, which operates five facilities in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, is not an official ministry of the Catholic Church, but Sister Marie Lucey, a nun with the Order of Saint Francis and associate director of the Franciscan Action Network, affirmed that the work is recognized and sanctioned by the church. A number of sisters in her order have volunteered there. “The work of charity and justice is very much in accord with Catholic social teaching and the gospel of Jesus we proclaim,” Lucey said.

Diocese of El Paso bishop Mark Seitz released a statement in support of Annunciation House, making it clear how the institutional church views the stakes of the conflict with Paxton. “We will vigorously defend the freedom of people of faith and goodwill to put deeply held religious convictions into practice. We will not be intimidated in our work to serve Jesus Christ in our sisters and brothers fleeing danger and seeking to keep their families together,” Seitz wrote.

Those religious convictions also lead Catholic laypeople to act. Donna Mehle moved to Corpus Christi in 2018, as migrant families were being separated under the Trump administration, and felt compelled to make immigration the primary area in which she would express her commitment to not only the gospel, but also the Catholic Church’s social teachings.

Catholic social teachings, which guide followers’ lives and work in society, are found in various church documents, but the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has distilled them into seven key themes. Four of the seven apply specifically to the people crossing the Texas-Mexico border, Mehle says: the life and dignity of the human person; the call to family, community, and participation; the option for the poor and vulnerable; and solidarity. The bishops, in their summary, describe solidarity in a deliberately global sense. “We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. We are our brothers and sisters keepers, wherever they may be. Loving our neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world.”

As a lay associate of the Sisters of Saint Joseph, Mehle said, she also partakes of the charism—the unique spiritual gift—of the sisterhood, which is “to be one with God, among ourselves, and all others.” Living so close to the border, she didn’t see how she could be one with her neighbor if she was not actively giving those in need the kind of assistance and advocacy she herself would want in their situation. Mehle started a border ministry at her Corpus Christi church that sends volunteers to respite centers, raises money and supplies for them, and hosts educational forums for the community to increase awareness about the complexities of the immigration system. “We have a duty as Catholics to participate in society and to seek the common good of everyone, especially the poor and the vulnerable,” Mehle said. For the state to close migrant respite centers “would be stripping me of that expression of my faith.”

It’s not that Catholics don’t value national security or the right of the United States to control its borders, Lucey said. “But it must do so in a way that is humane and orderly and compassionate.”

Respite centers such as Annunciation House are a vital part of both the humaneness and the orderliness of the border, and they exist in every major city along the Rio Grande. It is true that respite centers will serve people who cannot show legal documentation. But many, if not most, of the migrants served there are dropped off by federal agents—either Customs and Border Protection or Immigration and Customs Enforcement—meaning they’ve been vetted and processed and are now moving on to another destination. They either have a credible claim of asylum or cannot be deported because they are coming from a country with which the United States does not have a diplomatic relationship.

“Many of the agencies in charge of public safety have leaned on Annunciation House,” said Sami DiPasquale, executive director of Abara, a migrant aid and border education nonprofit in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. But he also sees cooperation with federal agencies as catnip for Paxton while Governor Greg Abbott quarrels with the Biden administration over Texas’s immigration deterrence program, Operation Lone Star. Courts have sided with the federal government over requests to cut razor wire at the border and remove Abbott’s floating border barrier. Abbott has pushed back, saying that the Biden administration is running an “open border.” “It’s all linked to SB 4 [a Texas law criminalizing border crossings between ports of entry] and efforts to push a state and federal showdown,” DiPasquale said.

He wasn’t making a leap. Paxton said as much in his press release upon filing suit.

“The chaos at the southern border has created an environment where NGOs, funded with taxpayer money from the Biden Administration, facilitate astonishing horrors including human smuggling,” said Paxton in the release. “While the federal government perpetuates the lawlessness destroying this country, my office works day in and day out to hold these organizations responsible for worsening illegal immigration.”

But standing outside his office and looking directly at border walls, enforcement personnel, and razor wire, DiPasquale doesn’t see anything close to chaos, lawlessness, or an open border. The only people broadcasting to the world that the United States is letting anyone and everyone come in, he said, are Republicans. Paxton’s request for documents alluded to a more administrative chaos, one created by organizations that don’t require legal documents to render services. By offering shelter to migrants in the country illegally, Annunciation House is contributing to lawlessness, Paxton claims. But, DiPasquale said, plenty of community services don’t require a person to prove their immigration status before they are served. “I don’t think you could be levying accusations against Annunciation House without levying them against hospitals and other institutions that don’t require documentation.”

Even police departments in Texas have resisted efforts by the state government to enlist them in immigration enforcement. When Texas passed the “show me your papers” law in 2017, allowing police to ask about an individual’s immigration status during routine stops, police departments around the state expressed concern about the safety of their officers and their ability to keep communities safe.

The idea that the respite centers, with their clean water and cots, provide an enticement for immigrants—one of the arguments border ministries have been hearing for years—is absurd, said nearly everyone interviewed for this article. “Serving desperate folks in their time of need somehow entices them? I would say ‘no way,’ ” Reeves said. Talking about respite centers as some sort of “pull factor” reveals the fact that, globally, the “push factors”—the conditions migrants are fleeing—are beyond what many, probably most, Americans can imagine. Asylum seekers often arrive at the border ill, abused, and with little more than a backpack of possessions—all evidence of how desperate they are to be here. According to Reeves, “How people of faith respond is not going to change that equation.”

- More About:

- Ken Paxton

- Greg Abbott

- El Paso