This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Bob Bullock never stops trying to save Texas, even at a funeral. One day last spring he went to the state cemetery in East Austin for the burial of an old friend and there it was—another problem that all the other politicians had ignored, just like education and water and everything else. Uncut grass! Tilted headstones! Trash! Didn’t anybody care about Texas anymore?

A month later, the lieutenant governor was still talking about the experience as if he had uncovered the biggest scandal in state government. “We’re going to fix that cemetery,” he told me, rising from a chair at his conference table for the fourth time in fifteen minutes to prowl around his office, light a cigarette, pour some coffee, rearrange a stack of papers, any excuse to keep moving. “It ought to be the Arlington of Texas. Do you know who has the tallest monument out there?”

I was about to guess Stephen F. Austin, but Bullock wasn’t waiting. “E. J. Davis,” he said. His eyes narrowed, as if he were sighting in on a target. “That carpetbagger who was governor. It’s a disgrace.” He launched into the virtues of the cemetery—monk parrots in the trees, Confederate graves, monuments by famous sculptors—then switched seamlessly into his program. “Parks and Wildlife has hired somebody to do a master plan. We can get federal money to restore the Confederate part of the cemetery. Then we’ve got to get the flagpole and the trees illuminated at night.”

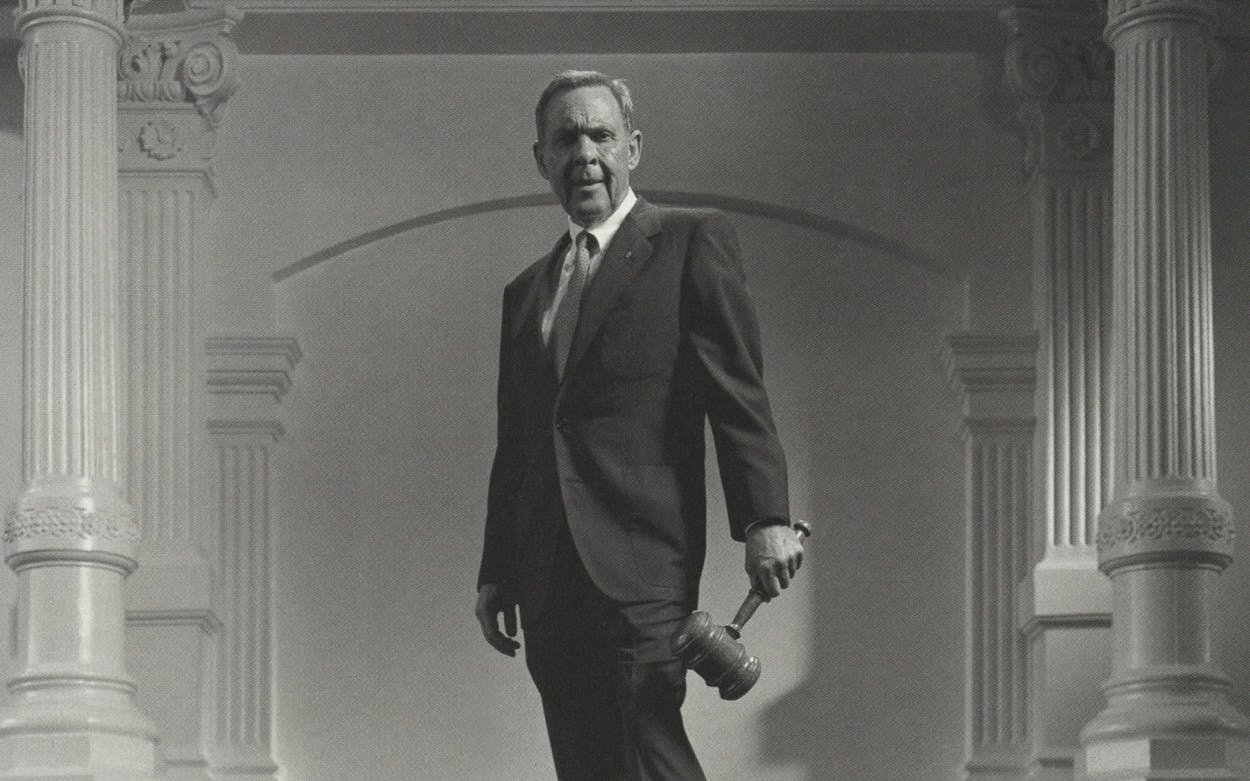

He sounded just like any legislator talking about his pet project, except for one thing: Bob Bullock presides over the Texas Senate, and he regards everything in state government as a pet project. From the biggest issues (the budget, education, crime, the business climate) right down to the tiniest details like the state cemetery, he has a position on everything, and his position is: Save Texas. Make it great, despite itself. This is a man who ends every public appearance with “God bless Texas”—and means it.

If you do not know Bob Bullock or his reputation around the Capitol, you might be thinking that he sounds a bit sentimental and idealistic. You could probably find an isolated passage or two that would lead you to conclude the same thing about Machiavelli. But that is not what either man is best known for. Bob Bullock is a master of power politics, a specialist in getting others to do his will.

He is, without question, the preeminent person of the moment in Texas politics. At a Bullock fundraiser last year, one of his aides heard a businessman say, as he wrote out his check for a campaign contribution, “Here’s my dues to do business in Texas for two more years.” The Senate is as eager as puppies to please him. Every major action of the last legislative session was a Bullock initiative: a no-new-taxes budget, more funding for long-neglected South Texas colleges, a school-finance plan based on capturing money from rich school districts, even a requirement that an income tax (which he himself had recently proposed) must be voted on by the public before it can become law. And that was just a start. At Bullock’s insistence, all sorts of ancient feuds were resolved by agreement between the protagonists: big business against plaintiff’s lawyers, truckers against shippers, farmers against downstream users of underground water. Now, forced negotiation—either you fix it, Bullock warns, or I’ll fix it—has become the standard way of handling turf fights in the Senate.

But it is not just what Bullock does that makes him such a dominant figure. It is how he does it. He wields power with astonishing effectiveness. Even the senators—Democrats and Republicans alike—seem a little amazed by their own docility. I asked John Montford, the Lubbock Democrat who is chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, whether he agreed with a lobbyist’s observation that Bullock is like a CEO and the senators have been reduced to vice presidents. Montford thought for a few seconds and said, “i’d say it’s more like an emperor.”

Power is the great mystery of politics. It is essential, but it is dangerous. How do you get it? How do you hold on to it? How far can you go in using it without abusing it? Bob Bullock understands these things instinctively. He is more than a student of power; he is the case study.

He has been a statewide elected official for twenty years—sixteen as comptroller, four as lieutenant governor—and yet Texans today know little more about him than his name. Bullock made his public reputation in his first months on the job as comptroller in 1975 by staging a series of raids on businesses that had failed to pay their state taxes. But as the years went by and the publicity occasionally turned sour (he had a penchant for flying around the country on state airplanes), Bullock became less and less visible. Today, at 65, he represents a disappearing breed of politician—the consummate inside operator.

In the media age, success in politics usually rests on charisma and ideology, the two assets that build mass constituencies. Bullock has neither. He doesn’t come across well on television, a medium that accentuates both the hollowness of his sleep-starved eyes and the twang that makes him sound like the small-town legislator he used to be. TV rewards politicians who transmit a relaxed congeniality—Ann Richards, for instance. If there is anything Bob Bullock is not, it is relaxed. A lobbyist who went hunting with him before the ethics laws changed remembers that Bullock’s khaki shirts and pants were stiff with starch, even at midnight. In Bullock’s presence, one is always aware of his intensity; he controls a conversation the way a tennis player runs an opponent back and forth across the court.

As for ideology, who knows? He has never been the sort of person to let philosophy stand in the way of getting something done. In 1991, during his first session as lieutenant governor, business-backed legal reforms died in the Senate when he chose not to rescue them. In his second session he made sure that the very same bills passed. He is a conservative who opposes new taxes and a liberal who increases state spending by $8 billion—in the same budget. His reversal on the income tax, from proponent to opponent, was ingenious. It stole the issue from Republicans, who wanted an outright constitutional ban on the tax. By proposing a referendum instead, Bullock not only protected himself politically but kept the door open for an income tax in the future.

Today he keeps his name before the public mainly through press releases. He never holds news conferences and makes few public appearances outside of an occasional speech. He is ill at ease when surrounded by strangers at parties and receptions; he has neither patience nor aptitude for small talk and almost never accepts the kind of ribbon-cutting invitations that most politicians love.

If his presence outside Austin is minimal, his presence inside the capital’s crowd of legislators, lobbyists, and bureaucrats is pervasive. They are fascinated by him. Senators, trying to figure out how little Bullock sleeps, compare notes on when he called them in the middle of the night. Lobbyists look for clues to his mood swings. Everybody wants to know who Bullock is mad at, because he is legendary for holding a grudge. (Twenty-two years after a group of senators blocked his appointment to the State Board of Insurance in 1972, Bullock chided the offenders, some by name, during an acceptance speech for an award given him by the University of Texas.) His on-again, off-again relationship with Ann Richards—it is hard to imagine two politicians more opposite in style than Mr. Inside and Ms. Outside—recently caused several lobbyists to skip a large meeting with Richards, lest their attendance be interpreted by Bullock as taking sides.

“She’s doing a bang-up job for Texas,” Bullock told me with uncharacteristic tact, but the examples he cited—lobbying General Motors to keep its Texas plant open, lobbying Congress to save the space station—took place far from his domain. Inside the Capitol, Bob Bullock, not Ann Richards, runs Texas. She is the symbolic head of state who makes public appearances and fills vacancies on agency boards, but Bullock runs the government. This is no slam at Richards: If George W. Bush defeats her in November, and Bullock wins his race for reelection as expected, Bullock will continue to run the government. The governor’s office is constitutionally weak, and Bullock’s determination to be in control is relentless.

His staff closely monitors every major agency. He knows that the state Supreme Court could have resolved the political battle over excessive punitive damages in a recent opinion but chickened out (“I’ve got three of them coming over this afternoon, and I’m going to jump ’em,” he told me). He knows that the Railroad Commission is waffling on trucking deregulation (“We passed a fine bill last time, and they didn’t implement it right, and we’re going to have another bill this session”). He knows every move that education commissioner Lionel “Skip” Meno makes (“We extended the school year five days so kids would have more time to learn, and you know what Meno did?—I ain’t high on his case—he gave it right back by giving in-service days for teachers”).

Bullock had run the comptroller’s office with the same total immersion, but the consensus among the inside crowd was that he would not enjoy the same success as lieutenant governor. As comptroller, he had dealt with bureaucrats whom he could (and did) fire at will; as lieutenant governor, he would have to deal with elected senators and partisan politics. “He’d better not treat the Senate like thirty-one department heads in the comptroller’s office,” was the standard line. I thought of that prediction recently when John Whitmire, the Houston Democrat who is chairman of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee, showed up at the July meeting of the board that oversees state prisons to criticize delays in the jail construction program. Whitmire left no doubt whom he was speaking for: “I’m here as a messenger for Mr. Bullock. . . . I’ll be judged on how well I’m doing my job in delivering this message. . . . My boss doesn’t like surprises.” He sounded very much like the department head for crime.

In politics, knowledge is power, and Bullock wants to be sure that he knows more than anybody else. He spends his days in meetings and reading briefing papers to prepare for the next meeting. He remembers a fact almost as long as he remembers an insult. My notes from our conversation are filled with Bullock’s references to what California and Massachusetts are doing to collect child support, what Tennessee is doing about Medicaid, and so on. He takes briefing papers home with him at night or to his two-hundred-acre ranch near Llano for the weekend. When he runs out of briefing papers, he reads news clippings, reports, and journals late into the night. His idea of a break is to pick up the phone and call a senator or a staffer. Everything in Bullock’s office is delegated, from responsibility for issues to making sure that his cigarette lighter is filled, and the rule is, If you know something, he’d better know it, no matter how insignificant. During a meeting with advocates for a job-training program, Bullock was surprised to learn that education was also on their agenda. “Did you know about this?” he demanded of the staffer who was responsible for briefing him. Yes, was the unfortunate answer. “Doesn’t anybody around here tell Bob Bullock anything?” he growled.

Nothing rankles him more than the failure to tell him what’s going on. I wasn’t surprised by the brouhaha over prison construction, because Bullock had said in our interview, “I’ve been a wee bit disappointed in the Criminal Justice Board. They haven’t kept me informed.” This was a recurring theme. “I had a real set-to with him,” Bullock said of his successor as comptroller, John Sharp. “I told him, ‘Look here, you’ve got to tell us what you’re doing.’” Of Austin State Senator Gonzalo Barrientos, Bullock said, “He won’t work with me, he won’t work with the governor, he has a chip on his shoulder, he won’t keep me informed. ”

Bullock wants to know everything. He reads small-town papers, and if he doesn’t like what senators are saying back home, he tells them so. His staff attends committee hearings that take place when the Legislature is out of session, and any senator who takes a position that Bullock disapproves of will hear about it. One lobbyist was recently summoned to the woodshed because he had told a reporter that he had communicated frequently with Bullock about an issue. Bullock held up a folder with the lobbyist’s name on it, and out floated a single letter. Once is not frequently.

This appetite for detail extends to gossip. His staffers report everything they see and hear, including who is seen with whom on the legislative party circuit. Bullock uses this information to disarm people face to face and to sustain his all-knowing image. One applicant for a job in Bullock’s office came for an interview after a breakfast meeting about another job outside the Capitol. Bullock let it drop that he knew about the earlier meeting—and what the applicant had ordered for breakfast. His favorite expression after dropping such tidbits is, “I just didn’t want you to think I’m asleep up here.” One does not have to undergo too many of these experiences before staying on the good side of Bob Bullock becomes a priority. He is proof of Machiavelli’s maxim that in politics it is safer to be feared than loved. Bullock is loved by some, but feared by all.

Yet, I know of no instance in which he has misused his power by killing a bill or adversely affecting public policy just to harm someone he didn’t like, nor has anyone else been able to cite one. (“No, I’ve never done that,” Bullock said.) Instead, he vents his wrath one-on-one, and a mighty wrath it is. (“I’ve done that,” he said.) He can explode with invective of the most personal sort. Ann Richards has been a victim. So have several senators—including his closest allies. So has, at one time or another, just about everybody on his staff.

“He has a sharply defined notion of how you’re supposed to behave,” said Bruce Gibson, who was Bullock’s executive assistant during the 1993 legislative session. “Some of it’s ethical, some of it’s practical, some is vision, some is loyalty to your beliefs, or loyalty to your state, some of it is hard work. He knows where the line is. When you fail to meet that standard, he gets right in your face and tells you where you’ve gone wrong. And there is always truth to it. ”

David Sibley of Waco, the unofficial leader of Senate Republicans and a Bullock admirer, told me during the last legislative session, “He’s the doctor, and he’ll tell you you’ve got cancer. ” Fear of a tongue-lashing is why all those issues that have eluded solution for so many years are suddenly being negotiated. People who get an assignment from Bullock are afraid to fail. No lobbyist dares even to miss a meeting called by Bullock, because he will get a public rebuke next time, and the news will race through the Capitol that ol’ Joe is on the outs with the lieutenant governor. When I asked Bullock how he had gotten the plaintiffs’ lawyers and business to work out their differences, he said, “I don’t think either side had been given the opportunity to be reasonable. I went to every meeting and no one raised their voice and no one got up and left.” On his face was a mirthless grin.

Of the elements that make up Bullock’s power, the most important is his sense of public purpose. If Bullock were aiming to run for higher office or to enrich himself and his pals or just to feed his ego on the banquet circuit, all his knowledge and all his threats could not hold the Senate together. He has been successful because he says corny things like “It’s a privilege to work for Texas,” and he believes them—and he expects the rest of the Senate to act as if they believe them too.

When Bullock says he’s for something because it is “good for Texas,” or because “I love my state,” no one snickers. No other politician could get away with that kind of talk. There was a time when he wanted to run for governor—he announced for the 1986 race in 1982 but abandoned the effort four months later with a public acknowledgement that he had seen no evidence of support—but those days are well behind him. He is eligible for social security, five times married and four times divorced, a self-condemning parent, a self-confessed former drunk, and a heavy smoker who has lost part of one lung. He suffers from frequent headaches and recently fought off pneumonia. At one time or another during his four decades in politics—as state representative from Hillsboro, as a lobbyist for automobile dealers, as an operative for Governor Preston Smith, and as comptroller—he has done most of the things he gets mad at his senators for doing.

He plays rough, no doubt about it. Any business leaders who think that Bullock’s current support for their agenda means that he has forgiven them for not supporting his income-tax proposal in 1991 are very foolish indeed. “Do you remember,” he asked me, “that the business community said Texas will never have major tax changes until we pass tort reform and trucking deregulation? Some day those folks are going to be held accountable for that statement.” He is out to clear the agenda for Texas, and woe to those who stand in his way.

Bullock raises the oldest of political questions: How much power is too much? His authority has all but eliminated the checks and balances of having 31 independent senators. He is the balance, and as for the checks, forget it: He has been known to get angry if a witness testifies against his program or a senator votes against it. This is not politics as it was envisioned by Plato or Thomas Jefferson, but is there any other way, amid all the obstacles to making government work—partisanship, ambition, envy, greed, inertia, intransigence—to save Texas? Is it enough to do the right thing for the right reason, if one does it the wrong way? These are troubling questions for many—but not for Bob Bullock.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Bob Bullock

- Austin