The most interesting—and far-reaching—issue of this legislative session is one that few foresaw: What is the balance of power between the governor and the Legislature? The emergence of this question came as a complete surprise to the politicians, lobbyists, bureaucrats, staffers, and reporters who ply their various trades at the Capitol, because all of us thought we knew the answer: Texas has a constitutionally weak governor and vests the power to create and oversee public policy in the Legislature through its ability to write laws and appropriate funds. As it happens, one person has a different view.

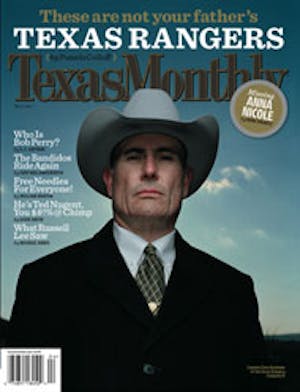

Rick Perry believes that, as governor, he has broad power to influence and even create, unilaterally, public policy in Texas. He has been bent on expanding executive power since his party gained total control over state government in 2003, a year in which the Legislature rushed through a bill giving sweeping new powers to the Texas Department of Transportation, including the ability to privatize highways; passed a reorganization of health and human services agencies that centralized power in a single bureaucrat appointed by the governor; gave the governor a $295 million fund to dole out to companies for economic development; and allowed him to participate fully in the process that crafted the state budget. In August 2005 Perry instructed the commissioner of education, by executive order, to institute education reforms that the Legislature had considered but declined to pass. He followed up that order with another one—since voided by an Austin judge—for expedited hearings on TXU’s request to build new coal-fired power plants.

But it was not until February 2 of this year that lawmakers woke up and finally said, “Enough!” That was the day Perry issued his executive order to Albert Hawkins, the executive commissioner of Health and Human Services, to institute a program requiring young girls, prior to the sixth grade, to be vaccinated against human papillomavirus, the cause of most cervical cancers. The order was hailed in some quarters and reviled in others. Women’s health advocates praised it. Parental-rights advocates—particularly those in the Legislature—strenuously objected, complaining that the vaccination was made mandatory rather than elective (although parents could opt out by signing an affidavit) and that adolescent girls were being immunized against a disease that is sexually transmitted. Longtime Perry critics rolled their eyes at the unsurprising revelation that the governor’s office had been lobbied by his former chief of staff Mike Toomey, now a lobbyist for Merck, the first drug company to market an HPV vaccine. But beyond the politics-as-usual reactions lay the larger issue of the extent of gubernatorial power. If a governor can do what Perry is attempting—establish a program that costs $71 million, including $29 million in state funds—the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches will be forever altered.

This is not an easy dispute to resolve. The Texas constitution does not directly address the subject of executive power. No clause says, “Texas shall have a weak governor” or “The legislative branch shall be supreme.” These relationships have to be inferred from our knowledge of history, the text of the constitution, and the presumed intention of the authors of the document in 1876: to undo the Reconstruction constitution that had been adopted seven years earlier. That instrument had created a chief executive with a four-year term and broad powers that included the appointment of all top state officials, including justices of the state courts. Edmund J. Davis, the first governor elected under the 1869 constitution, remains infamous to this day. The Reconstruction legislature gave him the power to appoint local officials, such as mayors, aldermen, and district attorneys. It created what was, in effect, a state press whose notices newspapers were required to print. It authorized a state police force that could take lawbreakers to another county for trial. Out of this debacle arose the present constitution, with an executive deliberately weakened by short terms of office (two years), fragmented responsibilities doled out to other elected officials, and a lack of express powers. The Legislature, too, was handcuffed, by being allowed to meet for only twenty weeks every two years.

By the time I came to work in the Capitol in the late sixties, the conventional wisdom (to which I subscribed) was that a major industrial state needed a full-time, professional legislature that met annually and a constitution that didn’t require amending before lawmakers could do something as simple as authorize the sale of liquor by the drink. In time, however, I came to appreciate its view that power should be diffused among the people’s representatives rather than centralized. I have seen no indication over the years that the public yearns for a stronger executive, which would amount to a government run by powerful bureaucrats, like the federal model. Whatever our problems are in Texas—and we have plenty—they can’t be blamed on our oft-amended constitution or on the governor’s lack of power. Blame them on ourselves.

What does the 1876 constitution tell us about executive power? Not much. The governor is the commander in chief of the military forces of the state. He can summon the Legislature into special session for purposes that he designates, grant pardons and commutations of punishments, make appointments to fill vacancies in state and district offices, sign bills into law or veto them, recommend measures to the Legislature for passage, and require information from other executive officers concerning their duties. And that’s all, except for one provision. In listing the executive officers, the constitution says, without elaboration, “[A] Governor, who shall be the Chief Executive Officer of the State . . .”

This is the language the governor’s office cites in defending the legality of creating policy through executive orders. “The chief executive officer has to have the ability to transmit information to state agencies,” Brian Newby, the governor’s general counsel, told me when I visited him at the Capitol. “He can pick up the phone or write a letter or use an executive order. It has the exact same effect as a letter or a phone call but shows the importance to the general public.”

But I think this answer begs a question: Does the constitution empower the governor to “run” the executive branch? Is he entitled to issue orders that create programs and policies? This subject came up in the 1998 gubernatorial debate between George W. Bush and Garry Mauro. The moderator asked whether the candidates would order their appointees to block a proposed hazardous waste site in a nearby county. Mauro answered that the governor should instruct his appointees on public policy (but, he now adds, he should not tell them how to vote). Bush said that Mauro’s view amounted to an “ex parte communication”—yes, he really said that—and that governors aren’t supposed to tell state agencies what to do. This is the traditional view, one that Perry clearly does not feel bound by.

“People expect the governor to act as the CEO of the state,” Newby told me. A staffer chimed in, “This is about the governor’s responsibility to be the leader of the state. This governor does not feel that he was elected to make appointments and go fishing for the next four years. He was elected to govern in a general direction.”

The contrary view comes courtesy of Scott McCown, a former state district judge in Travis County who is now the executive director of the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank. In a letter to Attorney General Greg Abbott concerning the governor’s constitutional authority to mandate the HPV vaccine program, McCown argued that Perry has no authority to tell Hawkins “how to exercise the authority assigned him by the Legislature.” I have no doubt that McCown is right. Ironically, the governor’s office agrees with him. “The agency can consider or disregard an executive order,” Newby acknowledged.

In practice, however, Hawkins will implement the HPV order unless the rulemaking process produces information that raises medical issues about the vaccine or public (or legislative) protests force Perry to back down. In other words, Perry may lack the power to compel appointees and high-ranking bureaucrats to carry out his wishes, but no one is going to tell him no—especially since Perry has been in office so long that he has made every appointment and has facilitated the hiring of loyalists throughout the executive branch.

The legislative branch can try to fight back. It can pass a law overturning an executive order. It can cut appropriations for the governor or for his pet projects. It can investigate whether he should have acted sooner in the scandal concerning sexual abuse of offenders in Texas Youth Commission facilities. The Senate can refuse to confirm gubernatorial appointments, starting with Hawkins. But the bottom line is that the Legislature can take action for 20 weeks every two years, and the governor can take action for 52 weeks every year. The governor has the advantage if he wants it, and Perry clearly wants it. It is ironic that a governor who has always struggled to achieve respect, both inside and outside the Capitol, and who was recently reelected with one of the smallest pluralities of any Texas chief executive, should be the one to mount a successful expansion of the powers of his office. But in politics, relentlessness pays off, and Perry is relentless in pursuit of his objectives. Keep an eye on the items in his legislative wish list that fail to pass: They could well reappear as the subject of executive orders.

Initially I thought Perry would lose this battle, and, indeed, he may well lose the HPV fight because of widespread opposition. But I think he’ll end up the winner on the larger who-has-more-power question. I hate to see this happen—not because of Rick Perry, but because I believe the current balance of power works. The legislative process is cumbersome and frustrating, but almost everything happens in the light of day, all interest groups get to participate, and there are few secrets. The governor’s office operates out of public view, people do get shut out, and secrecy is demanded. Greater gubernatorial power is the wrong course for state government, but—unless the Legislature fights back now—it’s the course we’re going to take.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry