I remember feeling a little nervous when the heavy door leading to Death Row clanged shut behind me. I didn’t really know what I would see. Having never walked the concrete corridors of a Texas prison, or any other for that matter, I didn’t know at the time that it was very much the same as any other cell block. Inmates stepped aside as we passed, eyes down, in their place behind a yellow line painted along the edge of the floor. I assumed it was prison protocol for any “suits” on the unit—outsiders important enough to be escorted through the cell block by an assistant warden. But I never asked.

It was the fall of 1990. Barely two years after graduating from law school I fell into a position as criminal law advisor and counsel to Governor William Clements as he neared the end of his last term in the office. Even though I never met the governor during the six months of my employment, I thought the position would fit nicely into my plan to return to my North Texas hometown in Montague County to run for district attorney. I was 31—and ambitious. I had been sent to Huntsville as the governor’s representative to witness a scheduled execution, but it was delayed. As we waited, the warden was more than pleased to show me around. I was “with the governor’s office.” Technically, almost his boss. Or close enough to make him very accommodating. The red carpet treatment was a bit heady. The respect was more for the office than me, but it had its perks. Visiting the country’s—maybe the world’s—most active death chamber was one. It should have been a solemn occasion, but to be honest I recall very little of it. Except the part where I visited Death Row.

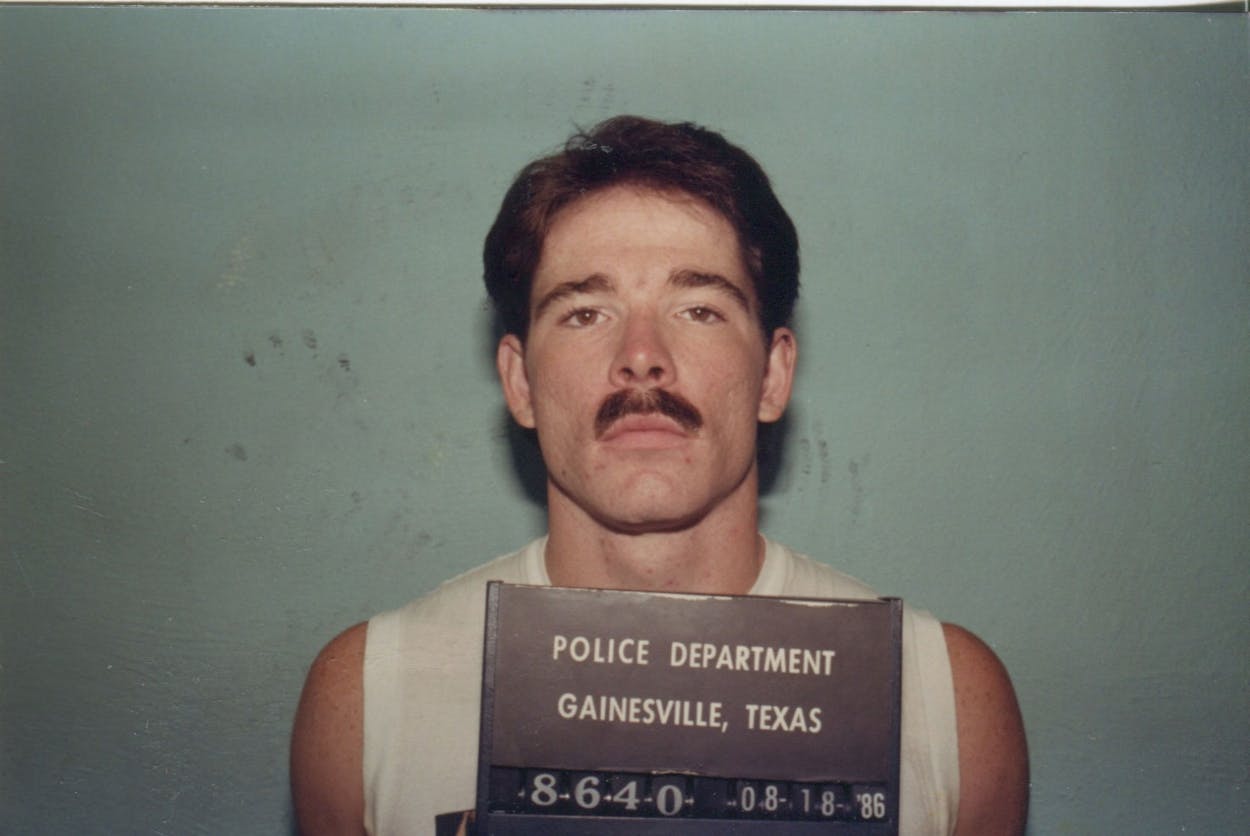

Near the end of the tour I mentioned to the warden that I actually knew someone on the Row: Clifford Holt Boggess, who was condemned to death for the murder of Frank Collier in July, 1986. I grew up in Saint Jo, a small North Texas town close to the Oklahoma border where Collier ran an old-fashioned family grocery store. It’s one of those places where everyone knows each other, and though I was a few years older than Boggess, I knew him. I knew his family. He knew mine. I probably had been in his home at some point as a child. At one point Boggess had worked a part-time high school job at the local newspaper owned and operated by my family. I never thought much about him after that. Until he murdered Collier and another man in nearby Grayson County in a three-week span of violence and became the only person in the modern era of the state’s death penalty from Montague County to be sentenced to die.

I still don’t understand why I did this, but I asked to see him. The cell was on the upper tier. Condemned prisoners on both sides of the cell block stood to look or stopped doing whatever condemned prisoners do to pass the time as I climbed the bare metal steps. The warden pointed out the cell and said something to the prisoner. “You have a visitor,” or “Someone is here to see you,” or something equally forgettable.

I quickly realized I had nothing to say to Boggess. He looked pretty much the same as I remembered. Short red hair. Glasses. I explained to him that I was working for the governor’s office and that’s how I wound up at Death Row. Unable to think of anything better, I simply asked how he was doing. “I’m okay,” Boggess said. “For someone on death row.” And that was all. Uncomfortable and with nothing more to say, I turned and left.

Eight years later, after I became the district attorney of Montague County, I received a letter from Death Row. Boggess wanted to choose the date upon which he would be executed. And I honored his request—he died June 11, 1998, his thirty-third birthday.

I guess little towns are pretty much the same everywhere. Saint Jo was no exception. There was one public school campus. The high school and junior high were both housed in a three-story dark brick structure built sometime in the 1800s. One year the beginning of the spring semester was delayed after the basement boiler that delivered heat to all the cast iron radiators in the building blew up. The “air conditioning” came from the breeze blowing through the open classroom windows.

Downtown was called “the square.” At its center stood an ominous looking wishing well covered by a metal grate, and a few park benches where old men whittled on sticks of wood. Some of them would retire to the domino hall every afternoon to gamble and drink whiskey, or so said the rumor mill. Over the years various businesses on the square came and went, but the cornerstones were the locally owned and operated bank and the little newspaper and printing shop run by my mom and dad. The bank, now a branch of a much larger institution, and the newspaper are still there. My parents, now 83, continue to turn out the same little newspaper every week. Technology and the Internet have found their way to Saint Jo, I suppose. You just can’t tell by looking at it.

Collier’s Grocery Store sat a half block north of the square, across the street from city hall and the tiny police station. Frank Collier was one of those perennially old men. At least he always looked old to us kids. But, then, most adults did. Neither he nor the grocery store changed much over the years. All the kids in town knew we could go there with a couple of soda bottles to trade for a few cents or some candy. The store had two aisles of wood shelves with rows of dusty canned goods. There was a small counter in the back where Collier cut steaks from big slabs of meat, and sliced cold cuts he wrapped in white butcher paper.

The checkout counter was one long metal table where, more often than not, Collier himself totaled up the purchases and made change, sometimes from his own pocket. Debit cards were a thing of the future. Checks were accepted. No ID required. Frank freely extended credit to those who needed “an account” until payday. He always carried a thick roll of cash bound with a rubber band in his front pocket. Everyone knew it. I never knew how much money he had stuffed in that roll. But it looked like a lot.

I have only a few childhood memories of Clifford Boggess. Nothing really stands out. He had a sister the same age as my sister. I vaguely recall seeing him at his house near the elementary school playground. I was six years older than him, so we didn’t run in the same circle. Plus I was too busy trying to be a king of the school, as Kenny Chesney sings, to notice the younger crowd. And he didn’t stand out much. It wasn’t until 1980, when he started working at my family’s business that I kind of got to know him. Even then, I recall little except that he was a studious looking red-headed teenager with glasses.

The job prospects in Saint Jo were meager for teens without a car but my dad took a liking to the stocky kid so he hired Boggess to help out in the print shop after school. His time there was uneventful except for an incident involving fifty dollars in cash that turned up missing from an unlocked cash box. Dad always suspected that Boggess came back in one night and took the money. Years later, as Boggess sat on Death Row awaiting his execution, that suspicion was confirmed by a letter from Boggess containing an apology—and fifty dollars.

College and law school took me away from Montague County for most of the eighties. At a young age I became fascinated by the law and politics. Although I was only four when JFK was shot in Dallas, I distinctly remember watching, in black and white, the flag-draped coffin atop the President’s caisson roll slowly down Pennsylvania Avenue. I’m still not sure if the memory is of the actual event or a film of it I watched later. But the picture in my mind seems very real. That early fascination would eventually lead me back to my hometown to seek political office.

I had just completed my first year of law school in Austin when I learned of Frank Collier’s murder. Dad was at the local hangout, the Dairy Queen, when he heard the news. The story quickly spread and gripped the town in shock and fear, followed by outrage. Saint Jo had its share of drug murders and passion killings by abusive spouses and boyfriends but nothing like this. There was always a running joke with Frank and his customers and friends that the big roll of cash in his front pocket would someday get him robbed and killed. No one ever really expected it to happen.

The crime scene revealed a brutal attack on the old man. His throat was slashed, his face bloodied and broken. The killer stomped so hard on Collier’s face that he left a shoe imprint. The shock was magnified four weeks later when Boggess, the kid everyone knew growing up, was arrested and charged with the crime. His guilt was never really in doubt. In the days before the murder Boggess talked openly about his plan to rob an old man who ran a grocery store and carried a lot of cash, and witnesses who knew him spotted him near the store shortly before the murder. Investigators spoke to the man who gave Boggess a ride and dropped him off near Saint Jo (the man was unaware of the crime Boggess was about to commit). A local resident who knew Boggess said he was the only customer in the store when she left about 7 p.m., just before the murder. Boggess, who was unemployed, bought a car with a cash down payment the day after the murder. Three weeks later, he walked into a second small grocery store in Whitesboro, 36 miles east of Saint Jo in Grayson County. There he used a shotgun to murder the store owner, Roy Vance Hazelwood, in a remarkably similar crime. If there was any doubt about his fate, it was now sealed.

The crime scene revealed a brutal attack on the old man. His throat was slashed, his face bloodied and broken. The killer stomped so hard on Collier’s face that he left a shoe imprint. The shock was magnified four weeks later when Boggess, the kid everyone knew growing up, was arrested and charged with the crime. His guilt was never really in doubt. In the days before the murder Boggess talked openly about his plan to rob an old man who ran a grocery store and carried a lot of cash, and witnesses who knew him spotted him near the store shortly before the murder. Investigators spoke to the man who gave Boggess a ride and dropped him off near Saint Jo (the man was unaware of the crime Boggess was about to commit). A local resident who knew Boggess said he was the only customer in the store when she left about 7 p.m., just before the murder. Boggess, who was unemployed, bought a car with a cash down payment the day after the murder. Three weeks later, he walked into a second small grocery store in Whitesboro, 36 miles east of Saint Jo in Grayson County. There he used a shotgun to murder the store owner, Roy Vance Hazelwood, in a remarkably similar crime. If there was any doubt about his fate, it was now sealed.

The 97th Judicial District, like most rural districts in Texas, included a multi-county area—Montague, Clay and Archer counties. With local sentiment solidly stacked against Boggess the trial was moved to Henrietta, in Clay County, about forty miles from Saint Jo. Then-district attorney Jack McGaughey requested the death penalty and got it. On October 21, 1987, after a brief deliberation, the jury sentenced Boggess to die. Though the case was locally sensational there was scant attention from the media beyond the North Texas area. I read about the trial and verdict on the front pages of the Saint Jo Tribune. In those days, instantaneous reporting from the Internet and 24-hour news networks were still a dream.

My political ambitions jelled as I worked in Austin for the statewide professional association for prosecutors, the Texas District and County Attorneys Association, as its general counsel. There I met most of the state’s elected prosecutors and quickly realized that the combination of high stakes trials with life and liberty on the line and the power of sitting in arguably the top law enforcement position in the county or district perfectly fit my aspirations. As did my brief stop as counsel to the Governor.

With little experience under my belt I went back to Montague County and challenged McGaughey, by then a seasoned three-term veteran, and won my first political race. I was 33, one of the youngest elected district attorneys in Texas—green, inexperienced, scared, and, at first, overwhelmed. I took the oath of office on January 1, 1993. By then Clifford Boggess had spent almost six years on Death Row.

When I became DA little remained to be done on the Boggess case. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction in 1991, and the last appeal to the United States Supreme Court was rejected on April 6, 1998. Boggess did not claim innocence. Over the years he stopped denying his crimes. There was no clamor to halt the execution. No claims of mental retardation or incompetency. To the contrary, Boggess possessed above average intelligence and had been by all accounts a good student. His appointed trial counsel, Robert Estrada from Wichita Falls, was experienced and highly regarded. There just wasn’t much he could do for his client. The execution was imminent.

I had little time to think about Boggess as his appeals process wound down. In October of 1996 the body of a sixteen year-old blonde cheerleader from Waurika, Oklahoma, just north of Montague County across the Red River bordering the two states, was found floating in a muddy creek bed near the river. Her name was Heather Rich. She was a pretty, popular girl—raped, kidnapped and brutally murdered on a remote bridge by nine shotgun blasts to her head and back. Her killers were two seventeen-year-old schoolmates and a nineteen-year-old ne’er-do-well who had been incarcerated in the Oklahoma juvenile justice system for most of his teenage years. The case quickly caught the attention of the national media including a feature piece by ABC’s Prime Time Live program. I would spend the next four years after Heather Rich’s murder focused on the trials of her three killers. But in early December 1997, a letter arrived from the Ellis Unit in Huntsville, Texas—then the home of Death Row.

I was curious when I picked the letter up to read it. District attorneys routinely receive all manner of writs, requests, letters and such from prison inmates. They usually want something—a new trial, more credit for time served, a different attorney, complete freedom—you name it. But this one was different.

“Dear Tim,” it began. I wasn’t completely surprised by the use of my first name. We had grown up together after all. It continued: “This is not a legal motion but a simple ‘request.’ When it comes time to set my execution date, I would like to ask that the trial court set my date for June 11, 1998, if you have no objection. This is just a personal request from me to you.” Perhaps remembering the visit I made to him on Death Row years earlier, Boggess was reaching out to the only person he knew personally with any control over the decision to select the date of his execution. But why this date? A quick look at his file confirmed what I already suspected—Boggess wanted to die on his birthday. When a reporter later asked him why Boggess responded that he found a nice symmetry in leaving this world on the same day he arrived.

My initial reaction was predictable. Screw you. Why should you get to pick the date of your death? You didn’t give Frank Collier or Roy Hazelwood that choice. But as I thought more about Boggess and his victims and the death penalty in general, the why gradually turned into why not? The victims left behind will still have their closure, or whatever relief a loved one of a murder victim gets from an execution. He will still be dead. The State of Texas will get its chosen punishment. Why would it be any less justice to execute a man on the date he requests? Why does it really matter? And my answer was, it doesn’t—to anyone except Clifford Boggess. So, why not?

Boggess appeared in court one last time. On May 1, 1998, in a crowded but subdued courtroom in Henrietta, Texas, I watched 97th District Judge Roger Towery sign and file the order requiring the Director of the Institutional Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to carry out the sentence of death by lethal injection after 6 p.m. on Thursday, June 11, 1998. In addition to running the little newspaper, my father was also a Church of Christ preacher so I sat through a lot of funerals as I grew up. That’s as close as I can get to describing how that day felt. It felt like a funeral. I never saw Clifford Boggess again.

It may seem strange to say but I never really thought much about my feelings regarding the death penalty before I became district attorney. I was raised in a Southern conservative place with small town values by parents who believed in and practiced their Christian faith in every way. I guess support for the death penalty was simply a given.

During my years as DA I have prosecuted more than thirty murder cases. In seventeen of those cases I was faced with the decision—seek death or offer life. Three times I chose death. It was always difficult, but as I got older and more experienced, I felt the weight of the decision grow. I held the life of another human being in my hands. Of course a twelve-person jury plays a large part in giving the death penalty, but I could stop it. All I had to do was say life, and the prisoner lived.

I have heard all the arguments in favor of the death penalty. In fact, I’ve made them all—it saves lives of future potential victims; it gives the loved ones of the victim closure; it’s society’s ultimate response to the most heinous of criminal acts. But, in the end, it simply remains that the state has responded to the taking of a life by taking another.

The decision to seek death is the district attorney’s call. No one controls his or her decision. But there also is no question, at least in my mind, that there are factors that shouldn’t sway the decision yet do. As one simple example, I give you peer pressure. A death penalty case is akin to the Super Bowl or World Series for prosecutors. The stakes can never be higher than this. No district attorney wants to be known as the weakling who was afraid to take on the biggest case of his or her career. Some will say I’m oversimplifying it. But I’ve been there. I have faced the pain and anger of victim’s families as they talk of their expectations. In all those cases, I wondered how my decision would be judged. By those families, by the public who elected me, by my fellow district attorneys, and most of all, by the person I see in the mirror.

There are those who believe it inevitable that one day an innocent man will be executed. There are those who believe it has already happened. I just don’t know. What I do know is that as hard as we try to make it so, we are not perfect. Mistakes are made. Even the strongest death penalty supporters among district attorneys must acknowledge that mistakes happen. The safeguards built into the criminal justice system make it very unlikely that an innocent person will be convicted. But the intense media focus on recent DNA exonerations can make false convictions appear to be the rule rather than the exception. The truth is those cases are the exception, not the rule. Of course, try telling that to Michael Morton, a man who lost 25 years of freedom to the mistakes of the system and its reluctance to acknowledge those problems and correct them. And when it comes to the death penalty can we accept anything less than perfection? Can we, really? When the state seeks to take a life, there is no acceptable margin of error.

Death sentences are rapidly declining, both in Texas and the rest of the nation. In Texas alone, the number of death sentences dropped 75 percent since 2002. Several states currently are considering legislation to abolish the death penalty, and Maryland lawmakers just sent legislation to their governor’s desk that would ban it altogether. Capital punishment in the United States appears to be slowly fading away.

Over the years I have come to believe that the time for the death penalty has passed. As more and more states abolish the sentence, or declare moratoriums on carrying it forward, the death penalty will be given less and less until the day comes when the state no longer needs to take a life to make a point.

On June 11, 1998, I sat in my office at the stately old courthouse in Montague as 6 p.m. approached. I felt a vague emptiness while I waited alone for the time when I knew that Clifford Boggess would be dead. I felt that someone, somewhere had failed.

I stayed in my office until I was pretty sure that the execution had been carried out. Then I turned out the lights and went home.

I learned of the details of the execution the next morning from the brief description on the news. It was reported that he died with a strange smile on his face. All I knew was that at 6:21 p.m. on Thursday, the eleventh day of June, 1998, for me, the death penalty had a face. And red hair. And glasses.

Tim Cole has been a prosecutor for almost twenty years. He was elected to four terms as 97th District Attorney (1993 to 2006). Since then he has been assistant district attorney in the 271st District. He also served as Counsel to Governor Clements in 1990 and General Counsel for the Texas District and County Attorneys Association from 1988 to 1990. He has tried more than 150 jury trials, and his cases have been featured in Texas Monthly, and on various television programs including ABC’s Prime Time Live, American Justice, and Investigation Discovery.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Death Row

- Death Penalty

- Michael Morton