Shortly after being sworn into office in the early morning of January 1, Houston mayor John Whitmire went on a ride-along with police chief Troy Finner. After making public safety the central issue of his election campaign, the 74-year-old politician appeared eager to get to work. But as Finner turned onto Houston Avenue, a busy thoroughfare northwest of downtown, the police chief seemed more interested in discussing street design. He pointed out a series of concrete medians that had been installed the previous month as part of a so-called “road diet” that reduced the number of lanes from six to four. Finner told the mayor that the changes, intended to slow down traffic and give pedestrians a place to pause while crossing the street, were impeding first responders. “That’s dangerous, and it needs to be corrected,” Whitmire later recalled Finner saying.

That, apparently, was all Whitmire needed to hear. A few weeks later, city workers began tearing out the medians and returning the road to its previous condition. Typically, the city council member who represents the district where the medians were located would be consulted before their removal. But that member, Mario Castillo, told me that he found out about the mayor’s actions from a constituent. The project snarled traffic for two months and cost nearly $1 million—ten times the expense of installing the medians in the first place. Questioned by city council members about the expenditure, Whitmire declared that there was “no price tag on safety related to this project.”

In a comical turn, the city is now trying to block journalists from obtaining public records about the project by invoking the Texas Homeland Security Act, which allows governments to withhold documents that “identify the technical details of particular vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure to an act of terrorism.” (Whitmire and Finner declined to be interviewed for this story.)

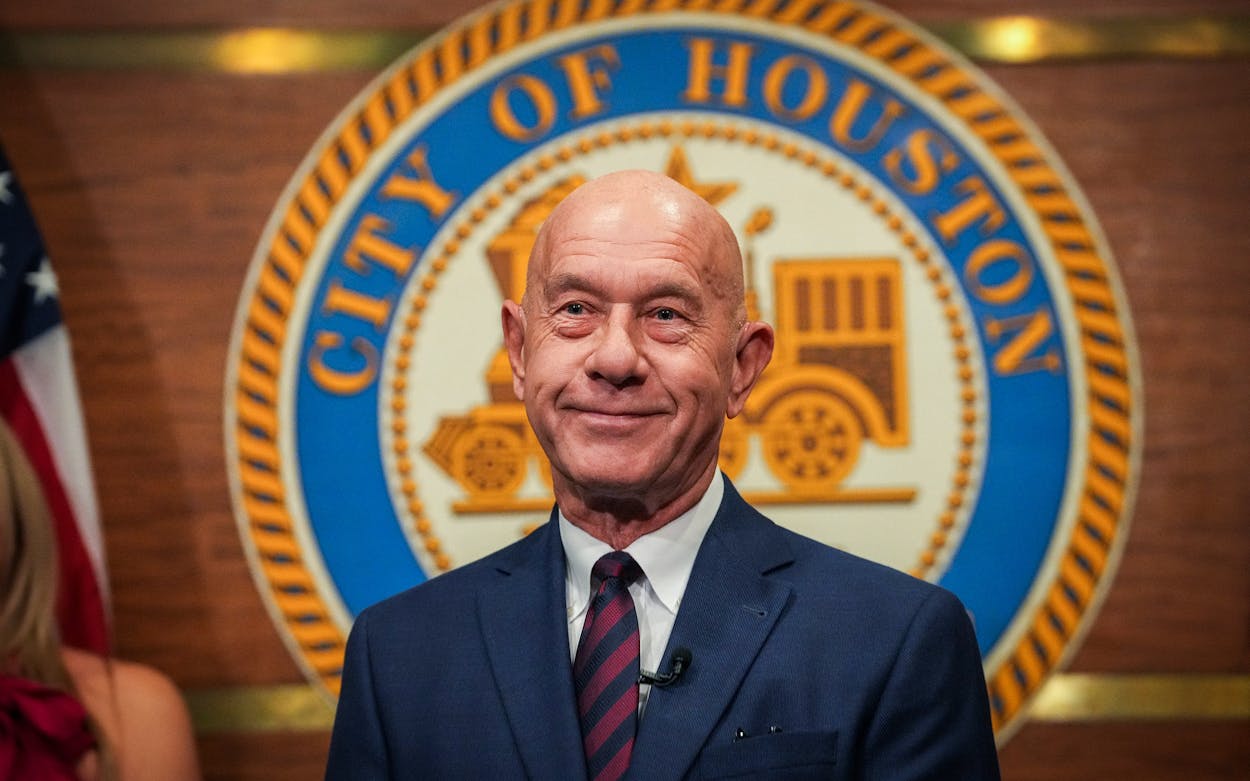

Whitmire, with a mischievous grin and a personality crustier than a day-old baguette, has only been in city hall for three months but he is already taking a jackhammer to the legacy of his predecessor, Sylvester Turner. During his eight years as mayor, Turner made road safety a priority. His administration redesigned dozens of streets, added protected bike routes, expanded MetroRail, and pledged to eliminate all traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2030—a goal known as Vision Zero. (In 2022, the last year for which complete statistics are available, 115 pedestrians and 11 cyclists were killed on Houston roadways. According to a 2023 study based on data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Houston is only the twelfth most dangerous city in Texas; Galveston has the most pedestrian fatalities per capita.)

Under Whitmire, the city has done a rapid about-face. Shortly after the new mayor took office, the city’s director of transportation and its chief transportation planner—well-respected professionals who had spearheaded Turner’s safe streets initiatives—resigned. In March, as Whitmire’s median removal was underway, the city put a temporary hold on all projects intended to narrow streets or add bike lanes. Later that month, after two pedestrians were fatally struck by cars within 24 hours, Whitmire called for better enforcement of traffic laws and urged bicyclists to stay off the roads. “I think the bikers need to be protected from the traffic, and they need to do that on bike paths that are recreational and not try to compete with people going to work and school,” he told a local TV station. He has blamed “anti-car activists” for the backlash to his decisions.

Several of Whitmire’s critics told me that the mayor’s view of Houston seems stuck in the 1990s, when cars ruled the road and everyone else got out of the way. “This is a mayor who sees bicycles as toys, not vehicles,” said Joe Cutrufo, the executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group BikeHouston. Rice University political science professor Bob Stein, who has known Whitmire for decades, described the mayor as “an old white guy who is comfortable with cars moving quickly.” Whitmire has also promised to expand the police force, crack down on homelessness, and work more closely with the Republican-controlled state government.

That approach seems just fine with the right-wing power brokers who banded together to elect Whitmire. A centrist Democrat who served in the Texas Legislature for more than fifty years, the mayor is on good terms with top state Republicans such as Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, who—in a notable break from his general hostility toward Democrats—allowed Whitmire to chair the state Senate’s Criminal Justice Committee. Whitmire campaigned for mayor as a pragmatist and problem-solver, painting his main opponent—longtime congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee—as a liberal ideologue. It worked: After the general election narrowed the field to two candidates, Whitmire easily beat Jackson Lee, 65 percent to 35 percent in the December runoff.

Can Whitmire solve Houston’s twenty-first-century problems with a twentieth-century approach? The signs so far are not encouraging. The new mayor’s first significant act was reaching a costly legal settlement with the firefighters’ union, which has been battling the city in court for years over a new contract. In exchange for dropping their lawsuit against the city, the firefighters will receive $650 million in back pay, plus up to a 34 percent raise over five years, which will cost the city an additional $400 million over the life of the contract. Whitmire argues that the deal is preferable to the possibility of losing in court, which could expose the city to even higher costs.

But given Whitmire’s longstanding ties to the firefighters’ union, for which he once worked as a lobbyist and which endorsed his mayoral campaign, many see the settlement as a quid pro quo. Whitmire has yet to explain how he intends to pay for the billion-dollar deal. For perspective, the fire department’s entire 2024 budget is $593 million. “This wasn’t a negotiation,” said one former city hall employee who requested anonymity. “This was a complete f—ing surrender. He basically gave them a blank check.”

Houston’s ability to raise money is limited by a property-tax revenue cap adopted by local voters in 2004. To comply with the ordinance, the city has had to reduce its property-tax rates nine times in the last ten years. Whitmire may have to ask voters this November to approve an exemption to the cap in order to fund the firefighter settlement. Other proposals include levying a garbage collection fee—Houston is the rare large city that doesn’t collect one—or cutting all city department budgets, except for fire and police departments, by 5 percent.

Even if Whitmire can come up with the money to pay the firefighters, there may be little left in the coffers to pay police and municipal workers, both of whose contracts will soon be up for renewal. The Houston Police Officers’ Union, which also enjoys close ties to Whitmire and endorsed him in the mayoral campaign, was less than thrilled with the deal he made with the firefighters. “If [the mayor] wants to make that agreement and put the city in thirty years’ worth of debt, that’s his prerogative,” HPOU president Douglas Griffith told me. “We just want to make sure we’re not going to bankrupt our city.”

The police department is currently mired in a self-inflicted crisis. In February, Finner revealed that since 2016 the department has failed to investigate more than 264,000 criminal complaints, around 10 percent of all complaints made during the period, including more than 4,000 sexual assault and child abuse cases. Detectives closed each of the cases using the code SL, which stands for “Suspended—Lack of Personnel.” Finner said he never authorized the code and was unaware of its widespread use, calling the situation “unacceptable.” The department has pledged to reach out to victims in each of the cases in hopes of reopening the investigations, and Whitmire has appointed an independent task force to determine who approved closing so many cases.

In fairness, the department does suffer from a dearth of personnel. Houston employs just 5,200 officers—around 350 fewer than 25 years ago, when the city was much smaller—to cover 2.3 million residents spread across 600 square miles. (By comparison, Philadelphia deploys 6,300 officers to protect 1.6 million citizens occupying just 142 square miles.) The Houston force is supplemented by the Harris County sheriff’s department and eight constables’ offices, but their combined efforts are widely seen as insufficient to handle the city’s needs. Nor is public safety Houston’s only challenge. The city is losing billions of gallons of potable water, and hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, because of thousands of underground water-line breaks. And it’s only a matter of time until the next natural disaster. Mayor Turner faced three 500-year floods during his time in office, culminating with Hurricane Harvey.

Given that Whitmire has never before held an executive office, many Houstonians are willing to give him something of a grace period. “Being mayor is very different from being a state senator,” observed University of Houston political science professor Brandon Rottinghaus. “It feels to me like he’s taking his time and getting his footing.” Michael Skelly, a prominent advocate for multimodal transportation, said he’s dismayed by Whitmire’s early moves but cautiously optimistic that the mayor will eventually see the light.

“Even if you don’t like to ride bikes or walk, as mayor you have to realize that every other city seems to care about this stuff,” Skelly said. “You don’t have to like that stuff yourself, but if you want your city to compete globally, you have to accept it. I think the mayor will come to that realization.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston