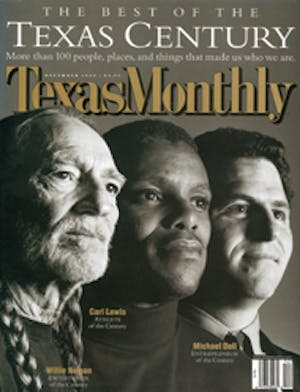

IN THE LENGTH OF TIME IT’S GOING TO TAKE YOU TO READ THIS SENTENCE, which should be just under ten seconds, Carl Lewis was able to bust out of the starting blocks at a track meet and run 100 meters at full speed, his thighs pumping like pistons, his arms slicing back and forth through the air. Think about it: He’d sprint the length of a city block in the same amount of time it would take you to pour a cup of coffee and carry it to the kitchen table. Then he’d catch his breath, head over to the long jump area, take a running start, plant his right foot on the long jump board, and propel himself at least 28 feet through the air—about the width of a two-lane highway.

Stand at your local neighborhood bar and jaw all you want about the glamorous baseball, football, and basketball stars from Texas. Shout out your precious statistics about who struck out what hitters, who scored which winning touchdowns, and who hit how many shots at the buzzer. The fact is, when it comes to individual athletic superiority, few people in the world can touch long, lean, and impossibly fast Carl Lewis, who came to Texas in 1979 to attend the University of Houston, immediately qualified for the U.S. Olympic team at age eighteen, and dominated his sport—all of sports, actually—for the next sixteen years.

In world-class track and field, where a single slightly strained ligament can mean the end of a career, sixteen years is an eternity. Yet staying healthy was the least of Lewis’ feats: He mastered both running and jumping events, which no one else has been able to do for the past half century. Although he didn’t get a chance to compete at the 1980 Olympics because of the U.S. boycott, the next time around, in 1984, he matched Jesse Owens’s record of four gold medals with four of his own. He added two more golds in 1988, two in 1992, and in 1996, at age 35, his hair flecked with gray, he won his final gold with a victory in the long jump.

“I’m finished. There’s nothing more to prove,” Lewis, now 38, told me recently at Café Noir, the stylish restaurant he co-owns near downtown Houston. Then he raised his eyebrows and gave me a knowing look. “But I’ll be honest with you. I know without a shadow of a doubt that I can stay in good enough shape to medal again at the 2000 Games.”

Even today, he continues to be a man of unbridled confidence—and he still refuses to apologize for being different. While he talked to me, he slipped off his shirt to pose for a photographer, revealing a ring in his pierced navel that matched the pair in his ears. Today, of course, such ornaments on a famous athlete are not particularly noteworthy. But who will ever forget Lewis’ ability to startle the public with his eclectic fashion sense? He’d turn up one day in cowboy garb, then another in a Robinson Crusoe outfit, and then arrive at a major track and field meet in a warm-up suit that not only was skintight but was also dyed the color of his skin, making it seem, at first glance, that he was naked. He was always changing his hairstyle in the old days, and he had the shape of his nose changed too, if you believe some press reports. Then there was his ad for Pirelli, the Italian tire manufacturer, that showed him in the “set” position, with his rear end up, and wearing a pair of red stiletto heels.

It is precisely because of his desire to do things his own way that so few of us regard him as an American hero. Despite Lewis’ long career and the quality and quantity of his achievements, it was impossible really to know him in the way we knew, say, Roger Staubach or Nolan Ryan. Over the years we booed him for what we considered to be his imperious superstar attitude, called him a grandstander, derided him as a rebel, and even passed on rumors about his private life. Through it all, though, Lewis never wavered. He ran his life as he ran track: at his own speed and at his own rhythm. “Do you want to know what makes me most proud?” he told me. “I represented change. It was very important for me to leave a mark, whether it was through the push for better drug testing of athletes or bringing professional pay to the sport or trying to pull the image of track and field out of the Dark Ages.”

WHO KNOWS HOW FAMOUS HE WOULD BE RIGHT NOW IF he had followed a more traditional path to athletic stardom? He was born in Alabama to William and Evelyn Lewis, who had been track and field stars themselves when they attended the Tuskegee Institute. They later became schoolteachers and civil rights activists, marching with Martin Luther King, Jr., in the early sixties. In 1963 they moved Carl, his two older brothers, and his younger sister to a Philadelphia suburb, where they started a track and field club. Little Carl dreamed about becoming the next Jesse Owens or Bob Beamon. He marked off 29 feet, 2 1⁄2 inches in his front yard—the record-setting distance Beamon had jumped at the 1968 Olympics—and tried even then to match it.

By age sixteen, Lewis was jumping nearly 26 feet and running the 100-yard dash in 9.3 seconds. He came to the University of Houston because of the reputation of track and field coach Tom Tellez, who taught him a more scientific way of performing (“Every movement in every event must conform to certain biomechanical laws” was Tellez’s mantra). In early 1981 the nineteen-year-old Lewis stunned the track-and-field world with a 27-foot, 101/4-inch jump at the Southwest Conference Indoor Championships in Fort Worth—the fourth-best long jump in history. He then entered the 60-yard dash and won it in 6.06 seconds, coming within two hundredths of a second of tying the world record. Although he remained in Houston to work with Tellez, he stopped attending U of H after only two years so that he could travel on the international circuit and start accepting endorsements: Nike gave him $40,000 to $65,000 a year in base pay just for wearing its shoes.

The 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles were supposed to be Lewis’ coronation, the time when the vast majority of Americans would pay court. But they were confused by what they saw. Before the Olympics, Lewis talked about how he had been taking acting and singing lessons, and he predicted that he would be “a respected entertainer” within five years. His own manager went so far as to tell the media, “We think Carl will be bigger than Michael Jackson.” Although he did do something in 1984 that will perhaps never be done again—he won gold medals in the 100 meters, the 200 meters, the 4 by 100 relay, and the long jump—the public saw Lewis as someone who was using his athletic career as a way to land big-money endorsements and get Hollywood’s attention.

During the finals of the long jump that year, he registered an opening jump of 28 feet, 1/4 inch, good enough for first place, and then passed on his next four attempts. Although Lewis was wisely conserving his strength for the later sprinting events—he also knew the other competitors would not come close to his one attempt, and indeed, they did not—the 80,000-plus fans at the Los Angeles Coliseum jeered him for not attempting a world record. By the time the Olympics were over, he was being called an arrogant and greedy athlete, the Maria Callas of the Cinders. After the 1984 Games, David Letterman had a young African American boy on his show dressed up to look like Lewis “What’s your name?” Letterman asked. “Gimme twenty bucks and I’ll tell you,” the boy said. The skit brought down the house.

“I couldn’t do anything back then without someone saying it was calculated,” Lewis told me. “Do you remember how I grabbed that big U.S. flag after the one hundred meters and carried it around the track? People said I had planted somebody there by the track with the flag. That’s completely untrue. It was pure luck that I saw the flag.”

At least he was adored by Europeans, who’ve always had a greater appreciation of track and field. King Carl, as he was known in Europe, received commercial endorsements overseas, and one of the albums he recorded sold more than half a million copies in Sweden. But in America, he was considered too far outside the mainstream to be a major product spokesman. Mary Lou Retton and other stars from the ’84 Olympics made the cover of Wheaties boxes, but not Lewis, whose sexuality was the subject of so many rumors that he felt obligated to deny them in his autobiography, Inside Track.

Still, Lewis kept getting faster and jumping farther, establishing a benchmark of greatness. Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson was so consumed with beating Lewis that he started taking large doses of illegal steroids before the 1988 Olympics. (Johnson did win the 100-meter final, but after he tested positive for drugs, he was stripped of his gold medal and it was given to Lewis, who had finished second.) At the 1991 World Championships, Lewis, then thirty years old, ancient for a sprinter, set a world record in the 100 meters with a time of 9.86 seconds, and in the long jump he leapt 29 feet, 1 1⁄4 inches—the best jump of his life. At that meet, he lost the long jump to Mike Powell, who broke Beamon’s world record, but Powell rarely came close to that jump again. Lewis, on the other hand, had gone undefeated in the long jump for a decade, winning more than 65 straight long jump competitions.

As the years progressed, Lewis never lost his ability to be controversial. He regularly attacked track and field’s governing body over the way it promoted its athletes (poorly, he believed). He fought for above-the-table payments for the sport’s stars. He led the charge to improve drug testing. He publicly confronted people he suspected of cheating, once accusing the great American sprinter Florence Griffith Joyner of using performance-enhancing drugs. Although Lewis himself never tested positive at a track meet for drug use, his allegations about the amount of steroid use on the circuit cost him the friendship of his rivals, many of whom will not speak to him to this day. He professed not to care. “My parents taught me there was a right and a wrong,” he said, “and that you speak out for what is right no matter how much you get criticized.”

What was often lost in the stories about Lewis was that he could be a genuinely affable person. It was true that he played a little too strongly to the cameras and to the crowd, inevitably raising his arms a nanosecond after passing the finish line. (He once admitted that he advised fellow sprinter Joe DeLoach to “make sure you keep waving” when running a victory lap.) But there was another side of him. In public, for instance, he never expressed anything but concern for Ben Johnson after Johnson tested positive for steroids.

By 1996, Lewis was the grand old man of track and field—but he kept training, hoping for one more shot at the Olympics. He turned to weight lifting, fine-tuned his vegetarian diet, and went to several little-known Texas meets, far from the network television cameras, to work on his sprints. Because of cramps he fared badly in the Olympic trials, barely making the team in the long jump. But at the Atlanta Games, he uncorked another nearly 28-foot jump at the very end of the competition to win the gold. The American crowd unleashed the kind of roar for Lewis that he had not heard in many years. Sports Illustrated, which had published more than one negative story about him over the years—“They basically said I was an asshole,” Lewis recalled—called him a “gentleman.” “Things have a way of coming back around,” he noted. “Don’t they?”

THESE DAYS LEWIS HAS A HOME IN LOS Angeles, Angeles, where he says he is actively pursuing his old dream of being an actor. He has created his own line of sportswear, SMTC (the initials of the Santa Monica Track Club, where he used to train), and it’s selling in such high-end stores as Saks Fifth Avenue. “I’m hoping we’ll soon be as well-known as DKNY or Prada Sport,” he said. “This is a new life for me, and it’s very exciting.”

But his old life is exciting too. Although he downplays it, he is still working out, lifting weights, cycling, running long distances one day a week and then sprints another day. His body is still cut to a fine edge. “It wouldn’t take him long to be back at a competitive level,” his former Houston coach Tom Tellez told me. “I don’t know if he could get back his old sprinting form, but he could easily outjump most people who are on the circuit now.”

I asked Lewis how often he thought about the next Olympics, where he might win an unprecedented tenth career track and field gold medal (he and Paavo Nurmi, a distance runner from the twenties, hold the record with nine.) “I don’t think about it,” he said. “I really am moving on.”

He paused and gave me an impish smile. “But I have to say, now that I think about it, it would be a nice encore, wouldn’t it?”