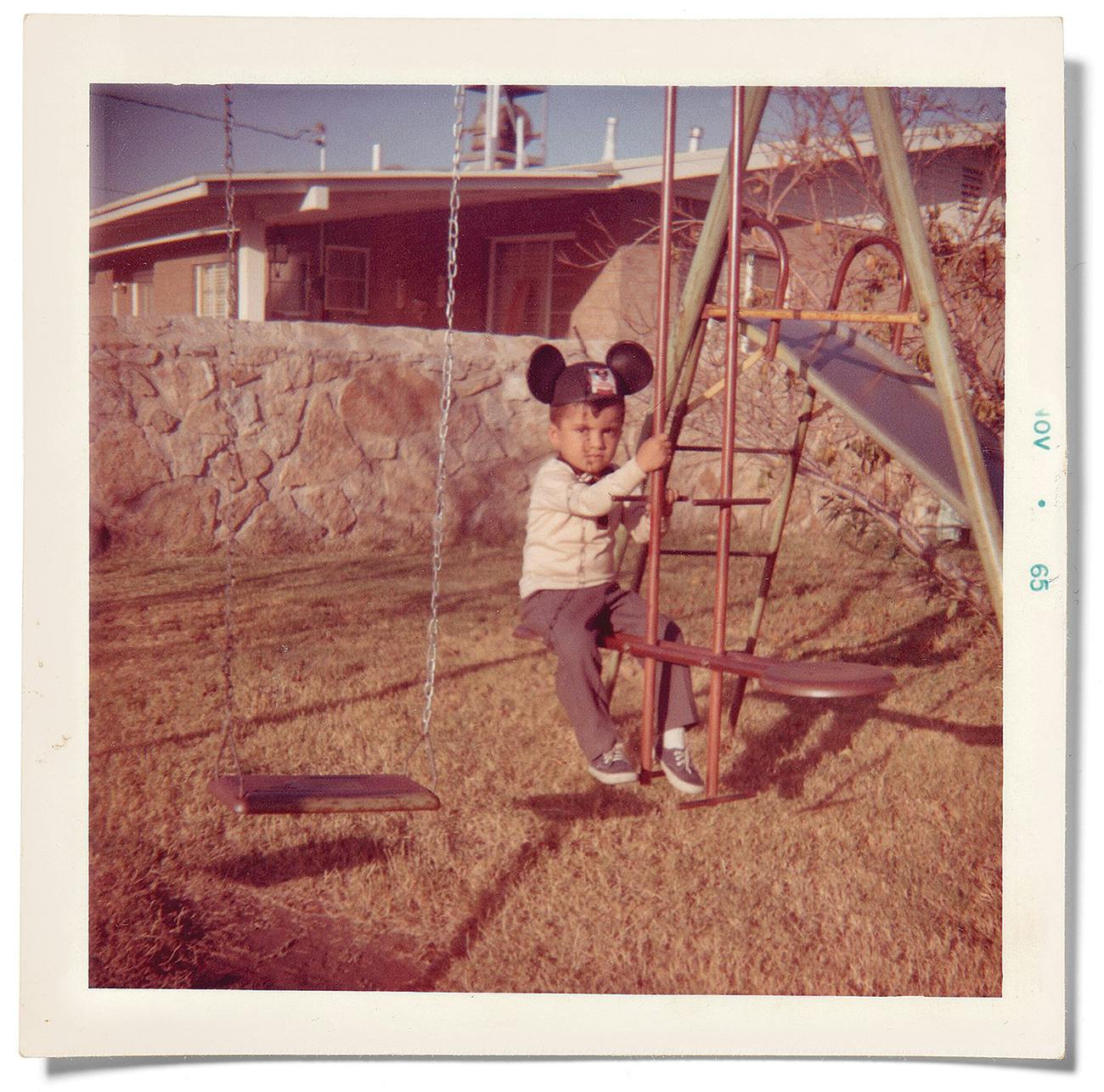

Growing up I had no idea of the multiple layers of meaning connected to the places I passed through every day. The layers opened up slowly. One such place was the Santa Fe Street international bridge, which links El Paso to Juárez. In many ways this binational thoroughfare best captures the essence of the fragmented city I’m from, a city originally called El Paso del Norte (the Pass of the North) that was later split in two along the Rio Grande. As a kid, going back and forth across the river was no big deal. We did it several times a week—to visit friends and relatives, eat at restaurants, and buy groceries in Juárez. For me the bridge was just a way to get to the other side of a muddy river. But as I look back, I realize that even then I could already sense that this narrow strip of concrete had deeper layers. My earliest memory of crossing the Santa Fe Street bridge from Mexico into the United States took place when I was about five years old. I was in the backseat of my father’s Mustang. When we reached the checkpoint, my parents took out their U.S. residency passports and showed them to the customs agent. The stern-looking man stuck his head inside the car window, pointed his finger at me, and asked: “Citizenship?” I wasn’t sure what he was asking, so I took off my Mickey Mouse hat and waved it in front of his face.

As an adult I still have trouble answering questions at border checkpoints. For some reason interrogations always make me feel guilty. Plus I find it difficult to answer the profound existential questions the customs agents pose at these crossings: Who are you? Where are you from? Where are you going? Why? They’re the sort of queries I’ve never been able to answer truthfully in five hundred words or less. I always simply answer “American” to the citizenship question. But what I really want to say is that I’m a fronterizo. I’m from both sides.

I come from a long line of paseños who went back and forth across the border most of their lives and who, like me, ultimately established deep roots in El Paso without losing their connection to Juárez. My maternal grandmother’s family immigrated to El Paso nearly a century ago during the Mexican Revolution. My great-aunt Adela Dorado, who was kidnapped by a Mexican federal soldier and later managed to escape, found refuge in the Segundo Barrio, a south El Paso neighborhood where much of the plotting and propagandizing for the revolution took place. Her family followed her, but as soon as the violence across the river subsided, many of them went back to Mexico. Others stayed in El Paso for the rest of their lives, while a few moved to California and South Texas. My tía Adela took my mother to work in the tomato and peach canneries in San Jose, California, in the late fifties. That’s where my mother met my father and where I was born. Before my first birthday, we drove back to the border on a truck that my father bought with money he had earned as a garbage collector in San Jose. He sold the truck to make a down payment on a butcher shop in Juárez. In 1965 he sold his butcher shop to buy a Chevron gas station in El Paso.

The first time my father entered the United States it was not through the Santa Fe Street bridge. He crossed into this country illegally in 1953 near the Tijuana border—just before Operation Wetback, which the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service claimed to have resulted in the removal of more than 1.3 million undocumented Mexican workers from the borderlands, either through actual apprehensions or by departures under the threat of deportation. A Border Patrol agent caught him and handcuffed him to a telephone pole while the agent chased after another unauthorized border crosser. Before handcuffing my father to the pole, the migra, who was pissed off at my father for running, threw my father’s sack lunch at his face. There was a bottle inside the sack that broke and gashed my father’s forehead. That was when he was fourteen years old. Many years later, not long after I graduated from Stanford—the same university where my father used to collect garbage as a young man—he took a pilgrimage of sorts. He returned to the exact spot where he had been handcuffed to the pole. There was a fancy restaurant near that spot, where my father and my mother sat down to eat the most expensive meal they could order. That was all the revenge he needed.

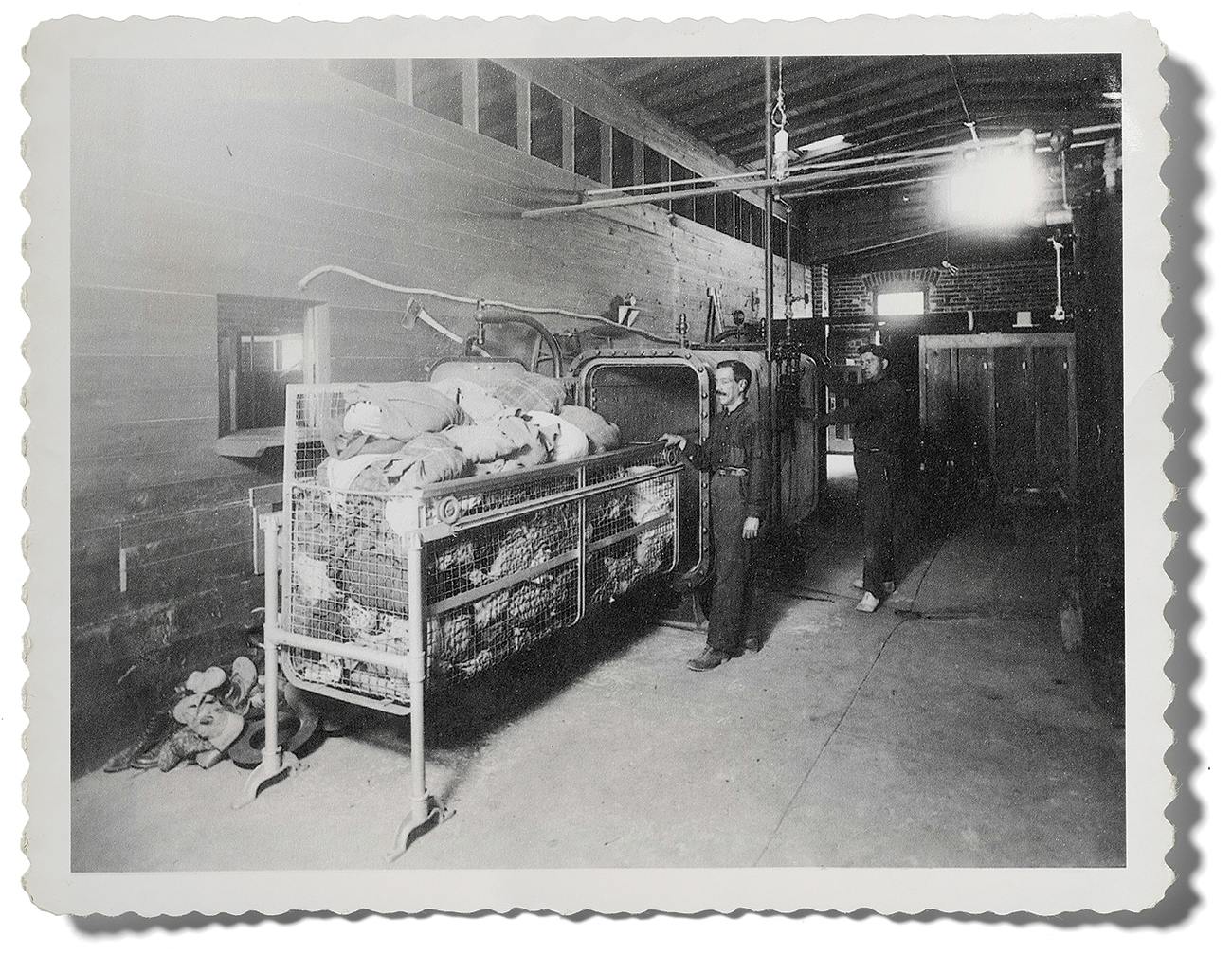

For decades my great-aunt Adela kept many of her own memories of crossing the border checkpoint to herself. It wasn’t until I was in high school that she first told our family about the fumigations at the Santa Fe Street bridge. We were all sitting around the Thanksgiving dinner table. She described humiliating experiences as a young woman in which she’d had to strip naked and be examined by public health inspectors when she crossed from Juárez to El Paso. Beginning in 1917, Mexican border crossers like her had to take a bath with a mixture of soap and kerosene and have their clothes sprayed with pesticides whenever they entered into the United States. My aunt, who always took great care to look her best, said she felt very embarrassed because the customs officials didn’t order everyone to bathe, only those they thought were dirty. Once, she had to put her shoes in what she called a huge secadora, and when she got them back, they had melted.

I had trouble believing this story. It certainly wasn’t anything I had been taught in school. I doubted whether the secadoras, or drying machines, she described had even been invented back then. Surely my great-aunt’s memory was failing her. At the time, I didn’t know what to do with her painful and inconvenient recollections. So I put them behind me.

When I entered the eleventh grade, we moved north of the freeway to what was then a predominantly Anglo neighborhood near Eastwood High School. My new home, on Alta Loma Drive, was far from my tía Adela’s neighborhood in south El Paso. Strip malls and residential developments were constantly cropping up on the East Side. The newly constructed Cielo Vista Mall, which was not too far from our home, was the only place in the city with a Waldenbooks, where I could buy books on literature and psychoanalysis. I wanted to be either a shrink or a writer when I grew up, so I bought everything I could find by Freud and Hemingway.

It was a big leap for me to move from my old neighborhood to the East Side. My first barrio had been located between an oil refinery and the sewage treatment plant, about half a mile from the borderline. I’d attended Jefferson High School—or “La Jeff,” as we called it—where there were only three Anglo students out of a total student population of about 1,500. Their names were Russell, Larry, and Sal. They were fully assimilated into Mexican American culture and spoke perfect Spanish, so I never really thought of them as white.

The kids at Eastwood High School, on the other hand, were very white. Many of them were Army brats from Fort Bliss. Some chewed tobacco, wore cowboy boots, and spoke with a thick Texas twang. I befriended a couple of blond-haired Mormon girls whom I found exotic. Even more strange were the many Hispanic students at Eastwood who didn’t speak a word of Spanish. This didn’t make sense to me. Speaking only one language on the border was like having only one eye.

Every Saturday we crossed into Juárez to visit El Rancho de Pío, the ranch owned by Pío Sandoval, my father’s closest friend. It was a magical place: wild turkeys, pigs, cows, horses, a swimming pool, a volleyball court, and dozens of acres of cornfields to play in. There I learned how to swim, how to milk a cow, and how to kiss a girl (not necessarily in that order). Dozens of families from both sides of the border made it a weekend ritual to gather there. While the adults made fresh corn tamales, played poker, or watched the Dallas Cowboys on television, we kids played fútbol soccer during the day and spin the bottle after sunset and told off-color “Pepito” jokes to one another. Pepito el pelado, the main protagonist of our jokes, was a sexually curious but naive boy who was always getting in trouble by asking adults uncomfortable questions at the wrong time and place.

As a writer and historian whose job it is to retrieve the past, I realize now that El Paso was a good place to grow up. I didn’t always feel this way. I spent most of my life trying to get out of “the Pass.” As soon as I graduated from high school I split. I studied in Palo Alto for four years, lived two years in Jerusalem, and five in Florence. About a decade ago, I finally exhausted my wanderlust and came back to where I’m from. I came back because I have history here, or should I say, layers and layers of history that I’m still learning how to uncover.

When I was in elementary school, I used to visit my tía Adela almost every weekend at her red-brick apartment building on South Oregon Street. I became a historian to a large extent because of my great-aunt and her old Segundo Barrio apartment. I remember the smell of mothballs in her room and photographs of her as an attractive young woman during the twenties. Her street ran from downtown El Paso to the Rio Grande. It’s in an area of town that used to be part of Mexico until the river shifted in the 1860s and it became U.S. territory.

Of course, as a kid I didn’t know any of this. All I saw when I looked out from Tía Adela’s apartment terrace were other century-old buildings like her own. I didn’t know that her neighborhood had helped spark the first major revolution of the twentieth century. Didn’t know that Mariano Azuela had written and published the preeminent novel of the Mexican Revolution, Los de abajo (The Underdogs), in 1915 in a building standing kitty-corner from her apartment. Didn’t know about the multitude of ghosts who had left their mark on her block. It was not until many years later, when I was doing research for my book, Ringside Seat to a Revolution, that I learned that Pancho Villa and radical newspaper editor Ricardo Flores Magón had plotted the overthrow of the Mexican government from rooming houses and newspaper offices on this street. So had Teresita Urrea, a young healer from Sonora whose name helped start uprisings from El Paso against the hated Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz in 1896. Urrea had lived a few yards down from my great-aunt’s apartment.

During the turn of the century, El Paso was the perfect launching pad for a revolution in Mexico. Having the largest ethnic-Mexican population in the United States and a location at the crossroads of major binational railroad lines made it the most strategic site along the 1,900-mile border from which to carry out gun smuggling, espionage, and recruitment and to publish newspapers denouncing the dictatorial Díaz regime. When New York journalist John Reed arrived in El Paso in 1913 in search of Pancho Villa, he wrote that “in every hotel and lodging-house a junta is in session at all hours of the day and night—revolutionary juntas, counter-revolutionary juntas and counter-counter revolutionary juntas.” Thanks to the Mexican Revolution, El Paso’s economy boomed. Local merchants made a fortune selling weapons, ammunition, and supplies to combatants on both sides. The director of First National Bank managed to double his profits by selling barbed wire to the federal troops and barbed-wire cutters to the revolutionaries. The business of revolution caused the city’s bank deposits to increase 88 percent between 1914 and 1920. During that same period, El Paso’s population nearly doubled in size. Most of the Mexican exiles who sought refuge in El Paso lived in my great-aunt’s neighborhood.

Before 1917, when freedom of movement was still a basic tenet of laissez-faire American capitalism, Mexican border crossers were not considered “illegal” in this country. El Paso and Juárez citizens could freely cross back and forth between the two countries without need of a passport. But the upheaval in Mexico that my great-aunt and her family fled from profoundly changed all that. Mostly because of the Mexican Revolution and World War I, that freedom was severely curtailed in 1917. That was the year the U.S. Public Health Service began bathing and fumigating with pesticides all “second-class” citizens of Mexico who crossed into the United States through the El Paso-Juárez international bridge. That was also the year that El Paso and Juárez effectively became two separate communities. For those of us with deep roots on both sides of the bridge, nothing has ever been the same.

Sometimes you have to go halfway across the globe to understand your own part of the world. I was sixteen years old the first time I visited Israel. I went on a Holy Land tour organized by my Uncle Rubén, a Pentecostal pastor from Laredo. We did all the required religious tourist stops: the Mount of Olives, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the Tomb of David, the Wailing Wall, the Temple Mount, et cetera. But what struck me the most during my visit was how much the partition between the Arab and Jewish sections of Jerusalem reminded me of home. After that first tour, I knew I had to revisit the Middle East.

When my sophomore year at Stanford ended, I enrolled at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I rented an apartment in lower Abu Tor, an East Jerusalem neighborhood that lies a few hundred yards away from the Green Line, which divides Israel from the Palestinian territories. Although I arrived at the start of the 1982 Lebanon war—long before the current border wall between Israel and Palestine was constructed—crossing the military checkpoints between the two zones was very much a déjà vu experience for me. The Israeli soldiers at the checkpoints asked those of us deemed suspicious the same kinds of questions the customs agents do at the El Paso-Juárez bridge—except in Hebrew. Mi eifoh atah? (“Where are you from?”) Lama atah kan? (“Why are you here?”) Lean atah noseah? (“Where are you going?”)

When you live in a war zone, the tension seeps into your body almost unconsciously. People get shot and blown up. You read about it in the newspaper; you hear about it from your friends; and sometimes it happens to people you know. But no matter how close it hits, it always seems distant. You function under the illusion that you’re living a normal life and that it—the endless violence—is on the other side of some imaginary line. Only occasionally does the tension in your gut remind you that war is all around.

In 1984 I came back to El Paso from Israel, but the tension did not go away. I brought the war home with me. Or maybe there had always been a war here and I just hadn’t seen it before. The concrete barricades at the Santa Fe Street bridge. The barbed wire. The Border Patrol checkpoints. The surveillance cameras and sensors along the river levee. The hovering helicopters. The floating bodies in the Rio Grande. Before, it had all seemed so normal to me that I hardly noticed. But I had come back with new eyes and now understood how abnormal everything was.

My great-aunt Adela no longer lived in south El Paso by then. She had moved to an assisted-living facility near the freeway. I visited her often in her new residence, and she would tell me astounding stories about her life in Mexico. She told me that Mexican soldiers had stolen her when she was twelve years old. The soldiers, under orders of a federal officer who wanted Adela for himself, forcefully abducted her from her village near Torreón and placed her in a burlap sack. During the revolution, she followed the man who ordered her abduction, often tied behind his horse with a lasso. He violated and brutally abused her for years. During one of his drunken rages, he threw a hot iron at her stomach. My great-aunt told me this was the reason she was never able to have children of her own. I was the grandson she never had.

When she began losing her memory, she had to move once more, from her assisted-living facility to an old folks home. She would often forget to turn off the stove, and it had become dangerous for her to live alone. When I went to visit her there, she didn’t recognize me at first. She looked at my face for a long time and asked, “Are you David?”

I nodded. Her eyes lit up and she smiled. “Remember when you were a little pip-squeak—una mirruña?” she asked. “You and your best friend, Fernie, were playing in the backyard and you got in a fight. He had you by the ankles over a hole both of you had dug, and you were slinging mud at his face. I came out and pulled you both by the ears and brought you inside the house. When I asked why the two of you were fighting, you looked at your little friend and asked, ‘Fernie, why were we fighting?’ And he shrugged and said, ‘Who knows?’ And right away—luego, luego—you went back out and started playing again.”

My great-aunt took obvious delight in recalling this story of childhood innocence. I, on the other hand, had completely forgotten it. Every time I went to visit she would tell the same story. But little by little, even these last vestiges of the past were erased from her mind.

Several years after her death, in 1997, I was doing research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., when I came across a photograph of a large steam dryer at the Santa Fe Street international bridge. Another photograph showed a pile of shoes belonging to Mexican border crossers undergoing the delousing process at the El Paso quarantine plant in 1917.

My great-aunt’s memory, it turned out, had not failed her at all.