Early in the third quarter, the Patriots fans at NRG Stadium sat with their hands on their heads, elbows out, while the Falcons fans in the room chanted “rise up” and sang Migos songs. Atlanta had just gone up 28-3, and Tom Brady—the greatest quarterback of all time—looked like his legacy could be tarnished. The biggest question in the stadium, and in living rooms across the country, was whether Matt Ryan, who was in the middle of delivering the best Super Bowl performance any quarterback ever had, deserved to be the game’s MVP, or if it should be defensive tackle Brady Jarrett, who was closing in on his third sack of Brady.

Of course, then things turned on a dime. The Patriots clawed their way back into the game, hitting a touchdown—but missing the extra point, bringing a wave of giggles to a stadium that saw a 28-9 lead no less indestructible than being up by 25—and then another field goal. Even then, a two-possession game with six minutes to play didn’t send NRG Stadium into “how is this happening” mode. The fans in red and black would have loved to see their team put more points on the board, but the celebratory mood from the first half was hard to puncture.

Live football is different from football on TV in that way: they say that the game is built for television, and they’re right in a few ways, but chief among them is that watching on TV transforms this three-plus hour game full of stops and starts into a narrative. The story is told to TV audiences in that time by announcers, experts, and sideline reporters. It’s told through shots of the tears on the eyes of the Patriots fan who had thought his team left for dead, who thought, “I paid $1,700 for a ticket to watch this” before realizing that there’s life left in Tom Brady’s battered bones yet. True students of the game may have realized by observing the Falcons’ defense that they stopped pressuring Brady and let him pick the team apart, but for many people the turnaround looked like magic.

And in a way, it was. The fifty previous Super Bowls had been settled in regulation, but this one required overtime. Once it got there, and the Patriots won the coin toss, anybody who hadn’t retired from making predictions with six minutes left to play in the fourth quarter had to have felt confident that this would be—yet again—Tom Brady and Bill Belichick’s night.

The emotional arc was familiar to a certain segment of the audience. In the weeks leading up to the game, a meta-narrative was applied to it: Atlanta, the city represented by civil rights legend John Lewis in Congress, up against New England—the team quarterbacked by “Make America Great Again” hat-sporting Tom Brady and coached by Bill Belichick, who wrote the president a fan letter during the campaign—turned the Super Bowl into a metaphor for the 2016 presidential election. The metaphor was flawed, obviously, but when Atlanta rose up in the first half, some of the audience that wasn’t in the 46.1 percent of the electorate that voted for Trump felt like they were getting some sort of metaphorical victory. Twitter was ablaze with people celebrating the Falcons’ win prematurely, embracing the team’s success like it was the easiest bandwagon to jump in sports history.

My TL looks like what November 9th shoulda looked like

— you (@MissZindzi) February 6, 2017

It was a familiar moment, a sort of déjà vu.

Sports and politics are tied in ways that go beyond the parallels that cast Atlanta as the avatar for frustrated liberals and the Patriots as Team Trump, in other words, and that was on display on screen (a lot of those commercials sure had a message) and off the field in Houston. The rumored political protest from halftime entertainer Lady Gaga didn’t really happen—unless you count singing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and her own hit “Born This Way” as a protest—but driving to the stadium, anybody attending the game was made aware that they were watching football in a polarized environment. Hundreds of protesters marched from Hermann Park to the stadium, just reminding people that the hours they’d spend watching Ryan and Brady were hours during which many had other concerns.

Protests that coincided with the Super Bowl were on the small side—20,000 people may have attended the women’s march in Houston two weeks earlier, but only about 500 of them made it out to Hermann Park—but they weren’t there to demonstrate against the Super Bowl, but rather the climate in which the game was taking place.

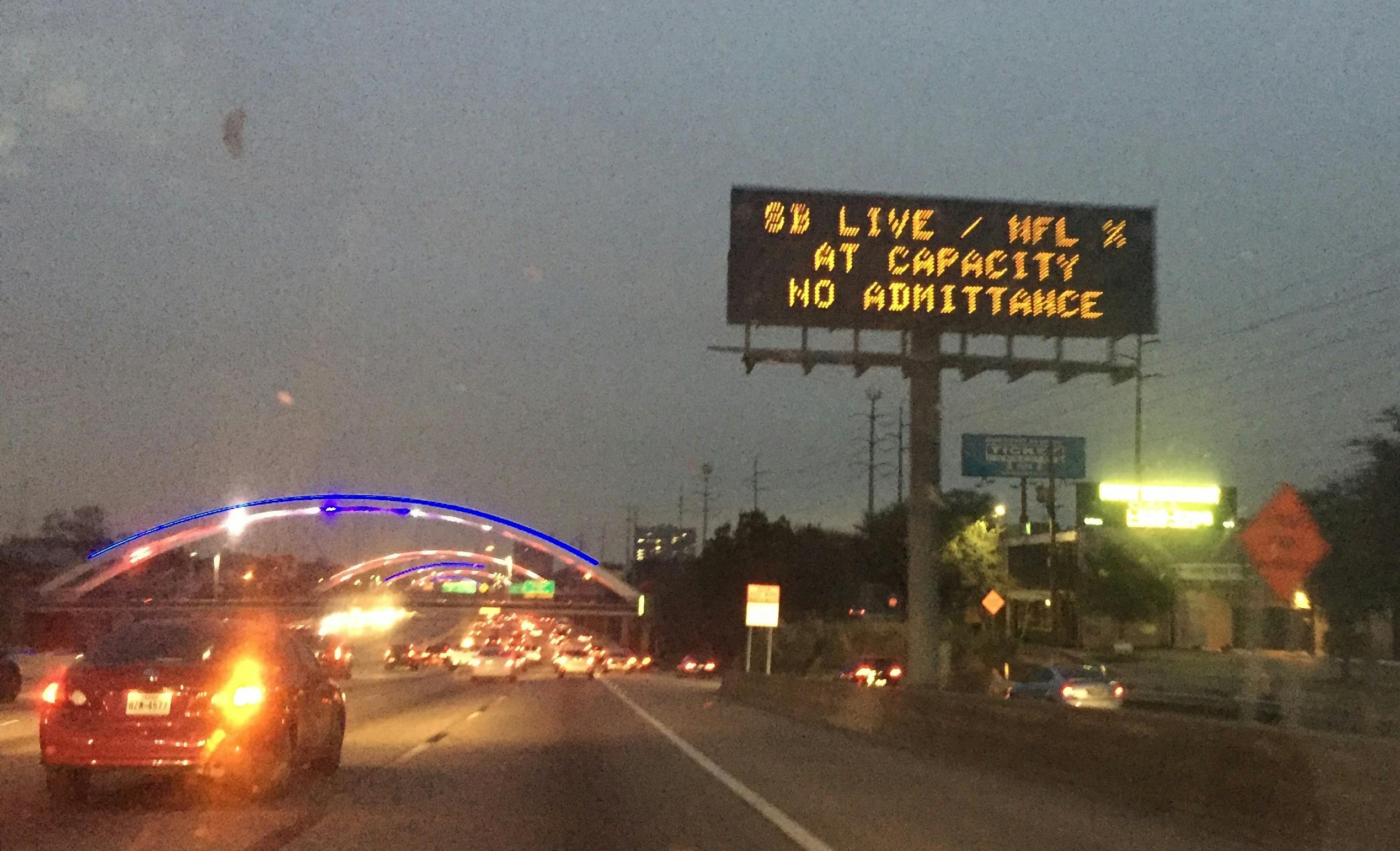

That atmosphere is relevant in a Super Bowl host city, if only because the message of populism that buoyed candidacies like Trump’s and Bernie Sanders’s resonates in unique ways when you’ve got a city dominated for a weekend by high-profile events with ticket prices roughly equal to that of a new Toyota Yaris. Stubhub’s average Super Bowl ticket cost $4,000, and that’s just to get into the stadium during the game. There was a lot of other things going on, of course. There was the NFL On Location package, where the NRG Center next to the stadium spent the hours before kickoff with live performances by OAR and Lady Antebellum, plus high-end cuisine ($5,949-$12,749 per ticket). There were the private concerts over the weekend, where fans could see superstars such as Bruno Mars, Taylor Swift, Sting, Travis Scott, and Nas play intimate venues. The Super Bowl brought a lot of luxury vehicles and high-end European sports cars to Houston streets, and whenever people are stuck in traffic trying to get to work because DJ Khaled is at a VIP event down the street, the gap between the haves and have-nots feels a little more pronounced. The city and the league put on public events that opened up the experience to the people of Houston who weren’t going to see Taylor Swift or to watch the game in person—Discovery Green featured superstar performances from Texas greats like Robert Glasper, Solange, and Leon Bridges. So certainly there were a lot of ways to experience the Super Bowl weekend in Houston.

Super Bowl LI might have been the greatest Super Bowl ever played (and given the down year in ratings the NFL experienced—and a lackluster playoffs that had only one game worth watching all the way through—the league sure needed that). Houston provided a backdrop for that game, and a home for an unprecedented comeback, a finish as dramatic as anything you might script, and the march of Brady and Belichick into a realm of greatness that went from “asterisk” to “unquestionable.” The city rose to the occasion of the event, and the event rose to the hype. So long as you’re not a Falcons fan, what more, ultimately, could you want?