Paraphrasing Hank Hill, just when you thought Lance Armstrong couldn’t get any scuzzier, he keeps doing sleazy things. Here is the latest, if you somehow managed to avoid it in yesterday’s news cycle:

Former pro cyclist Lance Armstrong was issued two traffic citations in January for allegedly hitting two parked vehicles in Aspen’s West End and leaving the scene — with his girlfriend apparently telling police initially that she had been behind the wheel in order to avoid national headlines.

Anna Hansen, a part-time Aspen resident who also lives in Austin, Texas, with Armstrong, also allegedly lied about whether the disgraced athlete had been drinking. She was cited for failing to report an accident and exceeding safe speed for conditions before those tickets on Jan. 12 were transferred to Armstrong, the former seven-time winner of the Tour de France who was stripped of his titles and eventually confessed to using performance-enhancing drugs.

Perhaps no Texas athlete has fallen from as high a pedestal as Armstrong, whose aura of invincibility transcended the sport he dominated for so long. There was the ubiquitous Livestrong bracelet. The days when he publicly palled around with President George W. Bush. The rumors that he considered running for governor. Even, as James Wolcott put it, “his name boasts an excelsior quality, like an American flag planted on the moon.” Now Armstrong is much better known for shame upon shame, scandal upon debacle.

Even before this latest fiasco, because his halo had once glowed with such blinding power, and perhaps because he so fantastically disappointed the public when he finally admitted to his lies, Armstrong had already become the poster boy for disgraced athletes, joining the ranks of O.J. Simpson and Michael Vick, even if Armstrong was neither an alleged murderer nor involved with the barbaric practice of dogfighting.

But he was not the first Texas athlete or the last to tumble Icarus-like from the heavens. Here’s a round-up of seven more. (Please note: this list excludes athletes like Jackie Smith who blundered in big games and didn’t live up to expectations, those whose careers were derailed by addictions, and those, like Michael Irvin, who have redeemed themselves in the public eye, post-scandal.)

Roger Clemens

With his direct, tough-guy pitching style and his stellar performances on the mound for both the national champion 1983 Texas Longhorns and for the 2005 Houston Astros, whom he helped take to their first and only World Series, Houston-bred Roger Clemens was a Lone Star State icon for decades, a fixture in H-E-B ads, and the most popular native-grown baseball player since Nolan Ryan. And whether you prefer your baseball stats advanced or traditional, Clemens was a far better pitcher than Ryan, which is no insult to Nolie, as according to the Wins Above Replacement metric, Clemens was the eighth-greatest baseball player who ever lived, second only to Walter Johnson among pitchers.

But then came the Mitchell Report, with its allegations of steroid use and accounts of the same by his one-time teammate and friend Andy Pettitte. Before it was all said and done, Clemens was accused of eight counts of lying to Congress about his steroid use. (Multiple accounts of adultery that surfaced around the same time further tarnished his image, especially the one linking him to doomed, drug-addled one-time-country-star Mindy McCready, with whom there was an unseemly age disparity.)

H-E-B dropped its ad campaign. Houston’s Memorial Hermann hospital excised his name from its former Roger Clemens Institute for Sports Medicine at Memorial Hermann.

Courtesy of his status as pitchman for sports memorabilia purveyors Tristar, Clemens’s visage also appeared on the outfield fence at Jessamine Field, the home ballpark for Bellaire’s little league. That gave rise to the following awkward, tragicomic scene in 2008:

“Wow,” commented one uniformed youngster, gazing at the image, to his teammate. “He really does look like he’s on ’roids!” A dad quickly hustled away his son, who wanted his picture taken in a sarcastically pumped-up pose in front of the Clemens ad.

And league board members were left to deftly field queries about the now-undesirable sign.

“We’re getting it down as soon as possible,” one explained. “It’s become an embarrassment.”

And even though he has since been vindicated on all eight counts of lying before Congress (thanks in no small part to Houston super-lawyer Rusty Hardin, also Adrian Peterson’s attorney), Clemens has not been cleared in the public eye, at least as far as Hall of Fame voting is concerned.

This year, the Rocket was again bypassed by most Hall voters, and today his credentials trail only those of fellow ’roid-tarnished superstar Barry Bonds (arguably the greatest hitter ever to play the game) among those not yet enshrined in Cooperstown. With both men’s vote totals hovering around 35 percent and the Hall requiring 75 percent or more, it seems likely that Clemens and Bonds won’t be getting in any time soon, barring a sea change in voters’ perception of the steroid era.

Mossy Cade

One of three first-team All-Americans on the most stifling University of Texas Longhorn defense in modern history, cornerback Mossy Cade was taken with the sixth pick in the 1984 draft by the San Diego Chargers. After Cade chose to spend a year with the Memphis Showboats of the USFL, the Chargers shipped Cade to the Green Bay Packers. In November of 1985, Cade raped his 42-year-old aunt-by-marriage and was later sentenced to two years in prison.

Cade’s case appeared among a spate of sexual assault accusations leveled against various Packers: Star wide receiver James Lofton’s trial was ongoing in the courtroom across the hall from Cade’s, and others were in varying stages of prosecution. With the team also performing abysmally on game days at Lambeau Field, Cade has gone into history as the living symbol of Titletown’s darkest era. Cade attempted a comeback with the Packers’ archrival Minnesota Vikings after his release from prison in 1989, but mass outrage among the Viking faithful caused the team to cut Cade three days into his final shot at NFL redemption. His whereabouts today are unknown.

Adrian Peterson

Even though he forsook the Horns for the Oklahoma Sooners, even the most ardent Orangeblood would have to admit that Palestine-bred Adrian Peterson was a joy to behold on the gridiron. (So long as he wasn’t lined up against the Horns.) No true connoisseur of the sport could regard his rare combination of power, speed, and agility with anything other than awe. Like Barry Sanders or Earl Campbell before him, Peterson was one of those rare players worth tuning in to watch on his own, even if you had no rooting interest in either team, or even an active dislike of the Sooners. Peterson’s domination continued in the NFL, where in 2012 he came just nine yards shy of breaking fellow Texan Eric Dickerson’s single-season rushing record and was voted league MVP.

The endorsements flowed in and Peterson’s charity work was widely renowned. To many of those who knew him, Peterson was as great a person off the field as he was at toting the rock between the lines. “He was one of the most down-to-earth superstars I ever met,” said former Vikings punter (and part-time pundit) Chris Kluwe.

Then the trouble started. First there was the report that Peterson had beaten his four-year-old boy with a switch vigorously enough to inflict slash-like welts. Then came the pictures to prove it. Montgomery County officials charged Peterson with the misdemeanor of reckless or negligent injury to a child, and Peterson was deactivated for the final fifteen games of the 2014 season.

In the aftermath of that incident, Minnesota’s Star-Tribune reported that back in 2011, a Peterson relative used a credit card from Peterson’s All Day Inc. charity for at-risk youth to pay for a seven-person orgy in a suburban Minneapolis motel room. That incident spawned a rape investigation that eventually ended with no charges filed against Peterson or any of the other other participants.

The 38-page police report details a night of drinking, arguing and sex that involved the running back, two relatives — including Peterson’s brother, a minor — and four women, in various pairs. One of those present, Chris Brown, a Peterson relative who lives with him in Eden Prairie, told police that he paid for the room using a company credit card for Peterson’s All Day, Inc.

As the night wore on, the report says, one woman who said she knew Peterson previously became upset when she saw him having sex with another woman. She started an argument that lasted at least an hour. According to the report, when she told him that she was “emotionally attached to him,” Peterson reminded her that he was engaged to another woman and had a baby.

Peterson pleaded no contest to the Montgomery County charge and was placed on probation, fined $4,000 and ordered to do 80 hours of community service. He remains suspended by the NFL until this spring, though the player’s union is fighting for his immediate reinstatement. It’s not too late for Peterson to restore his reputation to a certain degree, but time is ticking down for All Day, and it’s unlikely he’ll be inking any lucrative endorsement deals anytime soon.

Kluwe believes Peterson could be a force for change in society, that he could do for child abuse awareness and prevention what post-scandal Michael Vick has done for dog-fighting.

“Just like Michael Vick got a second chance after he was rehabilitated and serves as a spokesman for animal abuse, that would come ideally for AP if he would first figure out, ‘OK, why is this so harmful for people?’ Then he could really make a difference.”

Rangers on ‘Roids

A trio of Texas Rangers with face-value Hall of Fame credentials ranging from borderline (Jose Canseco) to rock-solid (Rafael Palmeiro) to downright platinum (Alex Rodriguez) also rank among the steroid era’s greatest villains. Canseco, the self-proclaimed Moses of steroids in baseball, outed Palmeiro (and fellow Rangers Ivan Rodriguez and Juan Gonzalez) as a ‘roid user in his 2005 tell-all / apologia for PEDs, Juiced: Wild Times, Rampant ‘Roids, Smash Hits & How Baseball Got Big. Canseco claimed to have personally injected Palmeiro with the drugs. Palmeiro was hauled before Congress a few weeks later and vigorously denied the accusations under oath: “Let me start by telling you this: I have never used steroids, period. I don’t know how to say it any more clearly than that. Never.”

And a few months after that, he tested positive for steroids and was suspended for ten days. Oops. Palmeiro then claimed that it was a mistake, that he had been slipped a performance-enhancing Mickey.

“I have never intentionally used steroids. Never. Ever. Period. Ultimately, although I never intentionally put a banned substance into my body, the independent arbitrator ruled that I had to be suspended under the terms of the program.”

In spite of his impassioned defense, or perhaps because of that very vehemence, and despite racking up more than 3,000 hits and 500 home runs in his career, Palmeiro’s Hall of Fame voting was so anemic, he was dropped from the ballot in 2014.

Long-gone as well are his days as a shill for erectile dysfunction drugs.

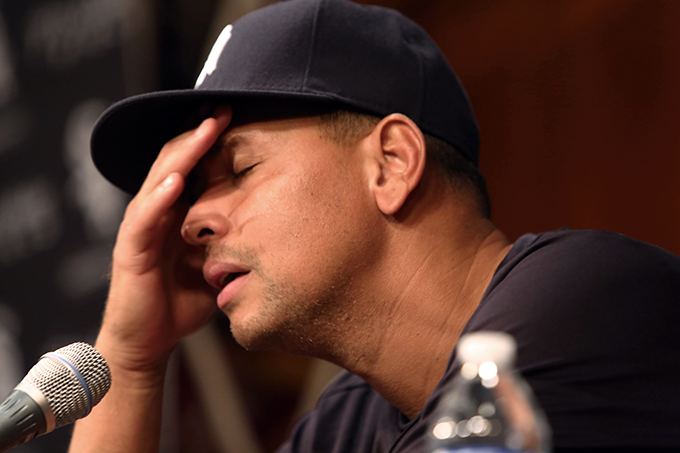

And then there’s A-Rod. Back in the nineties, if baseball had a Michael Jordan, it was the Seattle Mariners jaw-dropping, power-hitting, graceful shortstop, whose prowess out the plate only grew after his move to Arlington in 2001. In his three seasons with the Rangers, Rodriguez missed only one game and was the best player in baseball during that span. Six years later, Rodriguez admitted that he’d been juicing all through those years, but had since cleaned up his act. He’s been caught in lie after another ever since and is now one of the most reviled players in the game.

Which brings us to Lance Rentzel

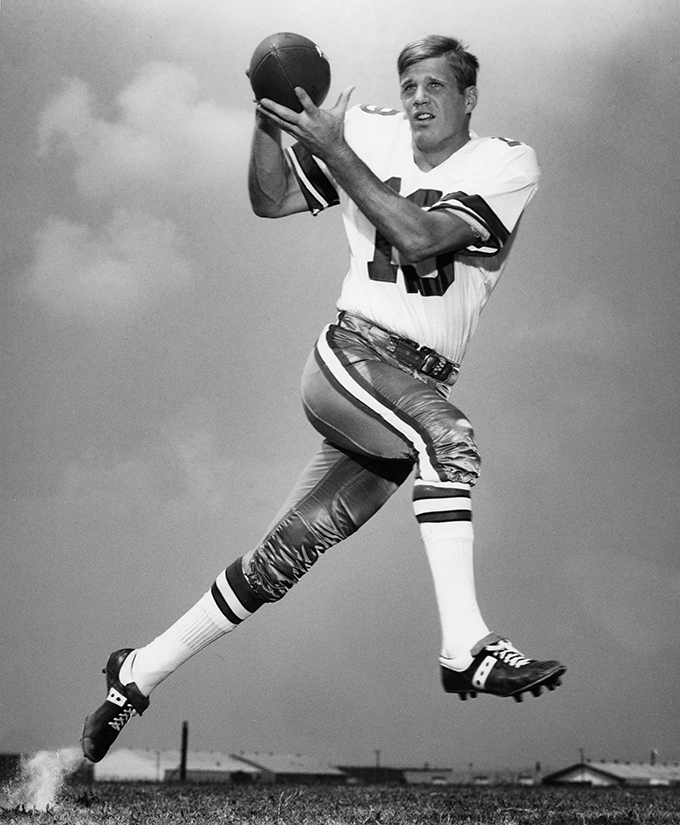

In November 1970, the world was at the Dallas Cowboy flanker’s feet. He was leading the Cowboys in receptions and was coming off a season in which he’d lead the league in touchdowns. He was also brainy, valedictorian at Oklahoma City’s exclusive Casady School, and talented enough to bang out more than a few tunes on the piano. And he was handsome enough to woo and win actress Joey Heatherton’s hand in marriage—their union was almost if not quite on the level of Tom and Gisele today. (One newspaper declared, that “the Golden boy [was] married to the most dazzling girl around.”)

And then one day Lance Rentzel threw it all away. While driving in his car on November 19, 1969, Rentzel spied a ten-year-old girl on a playground in Dallas’s University Park. He hit the brakes, beckoned the girl over, exposed himself, and drove away. The girl later recognized Rentzel on a TV commercial and the family pressed charges. That was when it came to light that Rentzel had been involved in a similar incident while a member of the Minnesota Vikings in 1966.

Those charges were downgraded to disorderly conduct, and after Rentzel agreed to seek psychiatric help, he was able to escape a full-blown scandal, even if the Vikings were more or less forced to trade him away from the scene of the crime. He wouldn’t get off so easy this time. News of this incident broke nationally. Fans started calling him “No-Pants Lance” and making wisecracks like “Don’t worry, even if we are down late, I’m sure Lance will put it out sooner or later.”

Below, Rentzel is pictured leaving the Dallas County Sheriff’s Office after posting bail.

Heatherton divorced him and her career lost its luster; some say she never recovered from the psychic shock of Rentzel’s offense. In 1971, Rentzel was sentenced to five years probation and court-supervised psychiatric care. By then he’d been shipped off to the Los Angeles Rams, where his career continued to spiral downward until it came to an end in after the 1974 season.

Even in the dark days following his arrest, one Dallas-area teenager never lost her faith in the Cowboys’ Golden Boy. Seventeen-year-old Linda Mooneyham was pregnant and unmarried, though the child’s father, Eddie Gunderson, eventually did tie the knot with her. On September 18, 1971, about seven months after Rentzel’s sentencing, the Gunderson baby was born, and Linda decided to name him Lance, after her tarnished gridron hero.

The Gunderson marriage lasted only a couple of years and Eddie signed away his parental rights to the toddler. In 1974, Linda married a salesman by the name of Terry Keith Armstrong, who adopted Lance Gunderson as his own.

And not long after that, Lance Gunderson name was changed to Lance Armstrong, and the rest is infamy.

(Photos of Armstrong, Peterson, Clemens, Rodriguez and Rentzel: Associated Press; Canseco, Rodriguez, Palmeiro, Gonzalez: Upper Deck.)