What, you might ask, would a fictionalized documentary about a child-sex ring at a rural Texas kindergarten and swingers club—a child-sex ring that never actually existed—look like? You can see for yourself at the Austin Film Festival Friday night, when Booger Red, a film by Berndt Mader, makes its North American premiere at 9:30 p.m. at the Spirit Theater, inside the Bob Bullock complex. Booger Red is based on a series of stories about the Mineola child sex case I wrote for Texas Monthly, beginning with “Across the Line,” from our April 2009 issue.

The stories entail a complex and messy series of trials and misadventures involving naive kids, trusting law enforcement, and manipulative adults—including one woman in particular who set the whole scandal in motion and, when it all played out two years ago, fled back to her native California. She plays herself in the movie, as do many of the actual characters who lived the real-life drama, from attorneys to adults (such as Booger Red, a.k.a. Patrick Kelly) caught up in her web of lies. One fictionalized character is the journalist, a fornicating, drug-snorting, bearded wild man who bears absolutely no resemblance to me.

Booger Red Trailer from Johnny McAllister on Vimeo.

Below, an excerpt from our original story covering the Mineola child sex case:

On August 11, 2004, readers of the Mineola Monitor, a weekly newspaper that serves much of Wood County, in East Texas, sat down to a familiar front page. “Area schools begin ’04 year next week,” one headline announced; “28th Annual Hay Show samples to be collected,” declared another. A photograph showed locals eating hot dogs at the Humble Baptist Church. “They braved the heat to enjoy music and good old-fashioned neighborly conversation,” read the caption.

Then Mineolans turned the page. Above the Community Calendar and next to the letters to the editor, they came to a story titled “Sex in the City,” in which regular columnist Gary Edwards revealed that a club for “swingers and swappers” was operating in town. The club was called the Retreat. There were twelve rooms, two hot tubs, a karaoke machine, a stereo, a big-screen TV, a sex swing—and a lot of beds. “We’ll do the operators of the facility a favor and we won’t say where it’s located for now,” Edwards wrote. “If they just move quietly out into the country . . . we’ll try and forget they’ve infiltrated our town with their set of moral standards.”

Swingers clubs are legal in Texas as long as no one is soliciting or paying for sex, and until Edwards’s column, the Retreat had been something of an open secret. It was located next door to the Monitor offices, in the former Mineola General Hospital, and its membership included locals as well as people from Tyler, Dallas, and Louisiana. The proprietors, Russ and Sherry Adams, lived just up the road in Quitman. On an average Friday they would host anywhere from fifteen to thirty swingers, most of whom the couple knew (the Adamses insist that the Retreat was not a club but an “on-premises party house”). “If we didn’t know them,” Russ told me, “they had to be known by other couples before they were invited to party.” Sherry would provide a snack buffet in the evening and then make breakfast burritos Saturday and Sunday mornings. “There are probably two hundred swingers within fifty miles of here,” Russ said. “It’s a lifestyle is all it is.”

Not, however, a lifestyle shared by the majority of the citizens of Mineola, a quiet town that’s home to 5,600 souls and a large number of antiques stores and Baptist churches. Edwards’s column about the swingers inspired more reader response than anything he’d ever written, and by early September, the party house was shuttered.

Things returned to normal, for about nine months. Then, on June 22, 2005, a woman named Margie Cantrell, who had moved to Mineola from California the previous year, showed up at the police station with a shocking story about the Retreat. Margie and her husband, John, were career foster parents who, after arriving in Mineola, had taken in four new kids. As Margie explained to the on-duty officer, one of her new foster daughters, eight-year-old Sheryl, had told her that she and Harlan, her six-year-old brother, had been forced to perform sex shows at the swingers club. (The names of all the children in this story have been changed.) The police couldn’t find any evidence or other witnesses, though, and the investigation was dropped.

Five months later, the case resurfaced in Smith County, Wood County’s neighbor to the south. This time the Texas Rangers were called in. And the stories got uglier: The kids had been taught “sexual dancing,” and they had been forced to have sex with each other at a “sex kindergarten” run by a guy named “Booger Red”; after “graduating,” they were made to dance, strip, play doctor, and have sex with each other at the club. The shows were videotaped, and in order to break down the kids’ inhibitions, they were drugged with Vicodin. According to the allegations, there were half a dozen adults involved in the sordid operation, including Shauntel Mayo, Sheryl and Harlan’s birth mother; Jamie Pittman, her boyfriend; and Sheila Sones, the kids’ maternal grandmother. Many of the accused had drug or alcohol problems and lived in rural Tyler. Though the swingers club was in Mineola, Smith County officials claimed jurisdiction because the alleged perpetrators lived there.

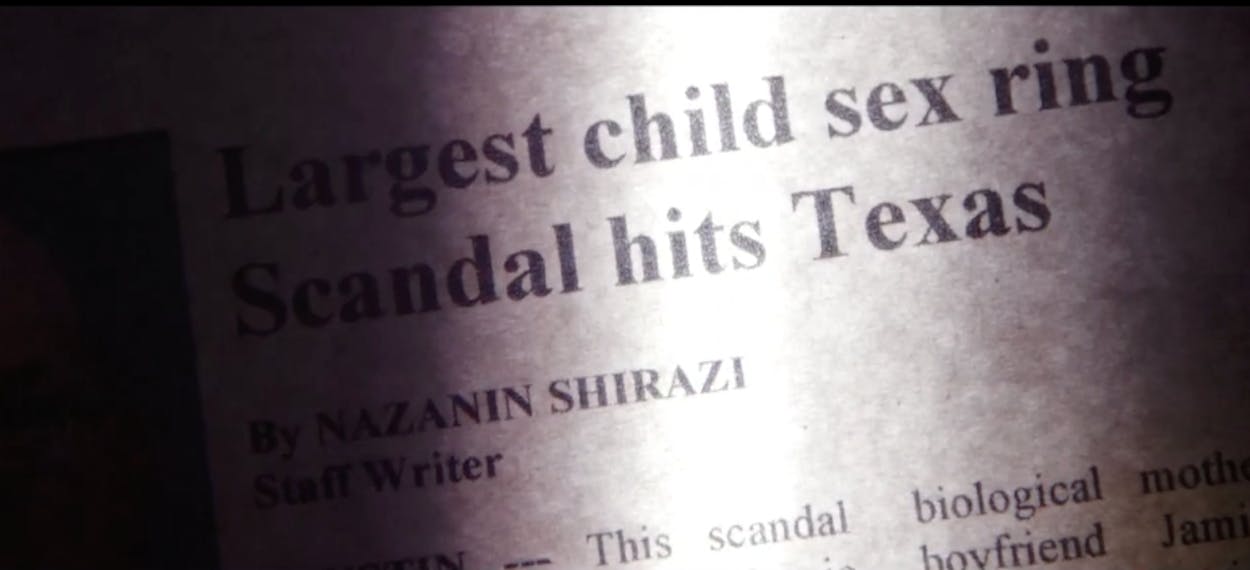

Investigators followed the case for a year and a half. Once again, no physical evidence or adult witnesses were discovered, but in July 2007, arrest warrants were issued for six people, including Mayo, Pittman, Sones, and Booger Red, a red-haired body shop sandblaster whose real name, Patrick Kelly, is rarely used, even by family. The salacious charges shocked East Texas. “6 INDICTED IN CHILD SEX RING,” screamed the Tyler Morning Telegraph’s front page. At the first two trials, held last spring, justice was swift and simple. Pittman and Mayo were each convicted in only four minutes, about the time it takes twelve citizens to stand up and raise their right hands in anger, and both were sentenced to life in prison.

But things were about to get a lot more complicated. Up in Wood County, a grand jury had launched its own investigation, prompted in part by local citizens demanding to know how an organized child sex ring could have run undetected for so long in little Mineola. And as the district attorney, Jim Wheeler, looked into the Smith County case, he began to have doubts. To begin with, Wheeler found out that back in 2005 two of John Cantrell’s former foster daughters, Sally and Chandra (not their real names), had accused him of sexually molesting them in California many years before. This information had never been mentioned during the trials of Pittman and Mayo. Wheeler also turned up more than a dozen swingers who went on the record with emphatic statements that there had never been any children in their party house. Wheeler later told me, “There was a total lack of corroboration for what those kids said happened.”

But Wheeler’s investigation had no bearing on the case being prosecuted 35 miles to the south. In Tyler, the kids’ testimony was enough, and the legal system marched on to the next defendant, Booger Red, who was convicted on August 21, 2008, and given life. By this point the story had gone national. “Trouble in East Texas,” Newsweek proclaimed. “A town is shaken by the saga of a child-sex ring.” Smith County assistant DA Joe Murphy summed up the feelings of many in the region and the rest of the country when he said, during Booger Red’s trial, “This case is about pure evil.”

That is the one thing, the only thing, on which everyone in this story can agree. But who are the victims? If Murphy and Smith County DA Matt Bingham are right, they are the children; if Wheeler is right, they are the defendants. How could the authorities in one county—the police, investigators, members of the DA’s office—arrive at such a different conclusion than the authorities in the county next door? Everyone looked at the same basic facts, saw the same interviews, and read the same reports, but Wood County found nothing, whereas Smith County found the worst child sex ring in Texas history. What really happened, if anything? The answers lie deep within a strange, winding story that covers two decades and two states and involves dozens of well-meaning adults and troubled children. We don’t yet know how the story ends; four more defendants are currently awaiting trial. But we know how it begins: with Margie Cantrell.

Read the rest of the story here.