There’s a buddhist parable in which several blind men argue about the appearance of an elephant after each has touched a different extremity. I imagine that early travelers to the vast area we now call Texas must have brought back similarly varied reports of their explorations, and today their ghosts might recommend that a prudent visitor pack both a wet suit and body armor. That said, a large part of the surface of our state is, like the skin of an elephant, a rough expanse of grayish brown, so the sheltering forests and sluggish creeks of the east are an unexpected sight. Though this region plays an integral part in the history of Texas, its cultural bequest is much more Southern than Western. Here, people whose ancestors fought the first battles for Texas’s independence live in swamps and eat squash, just like the indigenous Caddo Indians their forefathers disdained.

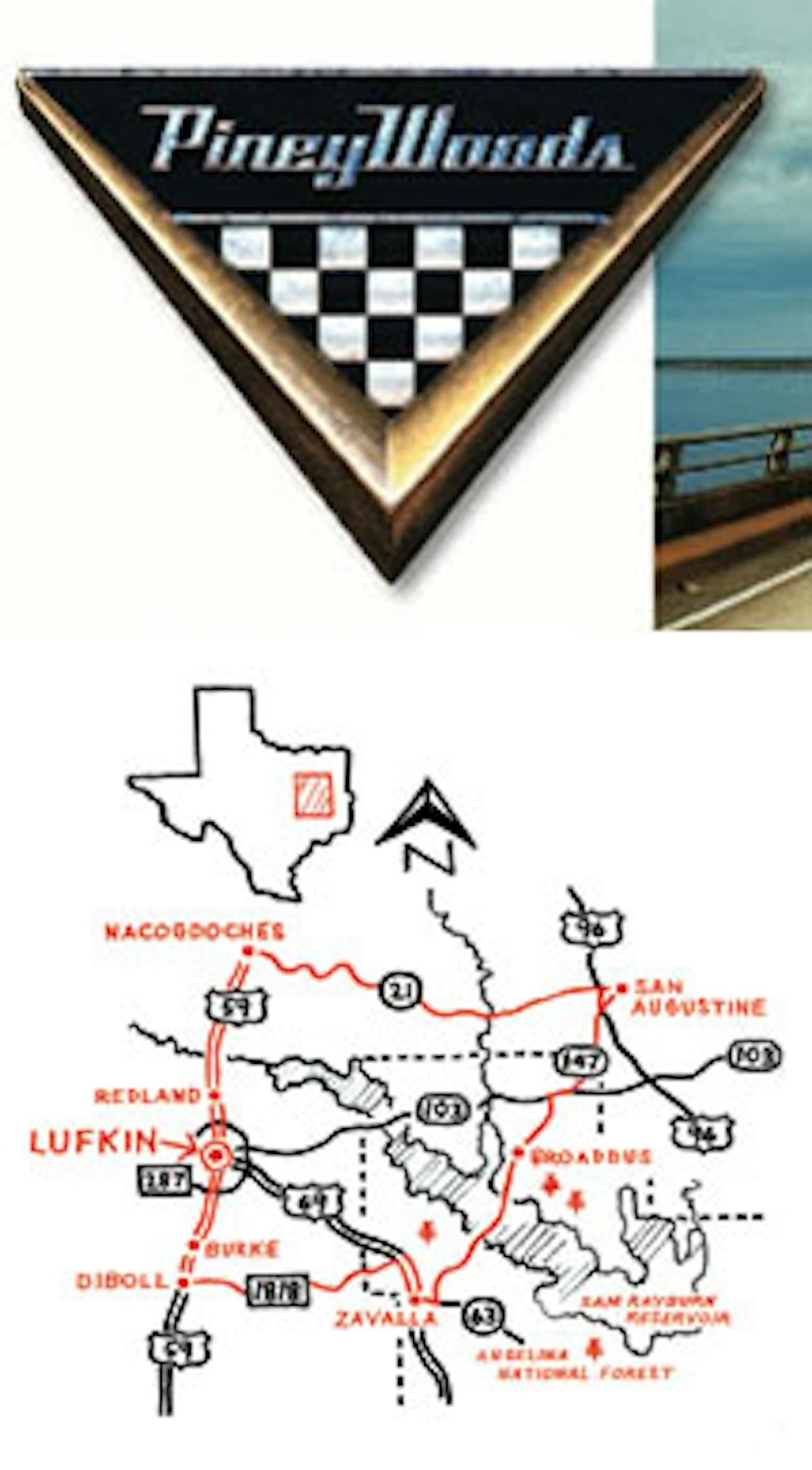

Today’s journey through the woods and small towns of deep East Texas will follow some of the Texas Forest Trail, a 780-mile loop of highways that takes in most of the region’s cities. Starting out from Lufkin, I head north on U.S. 59. Although the road runs from Laredo to Texarkana, I set my sights on reaching Nacogdoches, only 19 miles away.

Today the traffic is moving smoothly along this stretch of highway that swoops up and down, a gentle roller coaster of green hills. A brittle frieze of hardwood trees outlines a leaden gray sky. In the little town of Redland, the screen of an abandoned drive-in fills the horizon for a moment. I am taken aback at the countryside around me, since I had imagined this part of Texas to be as flat as the Panhandle. I think of northern France (something about the winter bleakness) and the Pacific Northwest, where pickups and timber trucks also rule the roads.

Five miles outside Nacogdoches, hand-painted boards advertise purple-hulled peas and sorghum at B.J.’s Farms Produce. I park under the big sign that surely features B.J. himself, plumply resplendent in overalls and glasses. Inside, jars of jam and jelly are stacked on wooden shelves, and bags of peas and beans fill several freezers. A lively woman welcomes me with a smile and tells me who made the blueberry jam I’ve picked out. She turns out to be Earline Allen, the owner’s mother. We talk for a while, and she waves good-bye from the doorway when I leave. In a few minutes, I arrive in Nacogdoches, the self-described Oldest Town in Texas, where, in 1832, the local settlers took the Mexican commandant and his men prisoner and freed East Texas from military rule.

There’s not much doing in the oldest town today. I drive across the loop road into the city center, where Yakofritz’s sandwich shop, on the courthouse square, is serving breakfast all day. As I enter, a man turns to look at me, and I am suddenly aware of my beard and long hair, today even more unkempt than usual. Feeling out of place, I walk through the long, dark, wood-paneled dining room to the counter. The restaurant’s decor brings Twin Peaks to my mind, though the many paintings of entwined hearts and smiling children soften this impression, and the staff is friendly, the food excellent, and the proprietor very helpful when I ask for directions to San Augustine. Climbing back into my car, I head east-southeast on Texas Highway 21. The road is lined with dark-green pines and ghostly hardwoods—trees, houses, cows, and fields framed against the chilly sky.

I love winter’s limited palette, but I bet this drive will be stunning in a few weeks, when all the trees are green, the dogwoods are blossoming, and the roadside is covered with wildflowers. The 36 miles of Highway 21 from Nacogdoches to San Augustine—part of the old Spanish Camino Real, or King’s Highway, which connected Mexico to Louisiana—twist and curve as if this were Ireland, though neither the forest nor the occasional clear-cut patches are exactly emerald in hue. The homeliest shacks along the way all fly the flag, and neat hand-lettered signs announce the hours of services at the white wood-frame churches sheltering in every bend of the road. If it were Sunday, I would attend a Pentecostal service just to see what really goes on in these humble buildings, which are just like those I have seen in documentaries about snake handling and speaking in tongues. Dirt tracks disappear into the forest on either side of the road, named after the householders who live just out of sight beyond padlocked metal gates. Everywhere there are signs pointing the way to small cemeteries. Perhaps it’s the subdued tones of the day, but this feels like a place where old people live, quietly transitioning to another world. Their carefully tended yards are dotted with birdbaths and rusting machinery, each item holding its own memory in the history of a lifetime.

San Augustine—the Cradle of Texas—takes shape out of the misty day a piece at a time, its buildings camouflaged among the creeks and tucks of the ground. Founded in 1832, the town flowered intermittently for a century or so before sinking back into its current gentle dishabille. I stop at the Mission Dolores Visitor Center (701 S. Broadway), open only on weekday mornings, and wait while the smartly dressed elderly woman in charge turns on the lights in the exhibit room, a little surprised to have a visitor on a cold Friday morning. Born and bred here, she’s curious about my travels and wants to make sure that I take in as much of the mission’s story as possible. Thanks to her, I can tell you that it was founded in 1717 by the Spanish, with the intention of getting rid of the French and “reducing and converting” the local Ayish Indians. The first Spaniards hacked their way through the area in the summer of 1542, trying to find a route through La Florida, as they called the southeastern United States, to New Spain, now Mexico. As I look into the display cases at worn pieces of leather and iron, I can almost hear the sounds of their axes and curses ringing through the unyielding timber.

From San Augustine, Texas Highway 147 heads south into the Angelina National Forest. Pine trees tower over the asphalt, and under their looming presence I speed toward Sam Rayburn Reservoir and Cassells-Boykin County Park, just off 147 eight miles past Broaddus. Despite the chill in the air, there are a dozen or so trucks and boat trailers in the parking lot. Out on the water, their owners stand on their flat-bottomed craft, wrapped in thermal jumpsuits, waiting for a bite. Surrounded by storage units, trailer homes, and cheap motels, the park is a sun-dappled oasis that must surely be packed on summer weekends.

Back on the highway, I am once again traveling along the bottom of a dark canyon of trees. Like a possum in a cornfield, all I can see of the sky is a strip of gray light overhead. But just before I come to the little town of Zavalla, the road crests a hill, and in the rearview mirror I catch a glimpse of where I’ve been. Stopping at the side of the road, I am rewarded with a hawk’s-eye view of piney woods spreading into the distance across the folds and curves of the earth.

Built on cotton, timber, and drilling mud, Zavalla was the center of a minor East Texas tung boom in the thirties, when entrepreneurs planted these Chinese trees hoping to get rich on the oil they produce. I stop at Coleman’s, a filling station and convenience store that opened in 1939. Its location, at the intersection of 147 and Texas Highway 63, seems to make it the hub of this down-to-earth little town. Pickup trucks pull up, and men in boots and jeans jump out to pump gas and buy tobacco. Only 647 people live here now, down from 1975’s peak of nearly 1,000, but Zavalla seems to be doing just fine.

I head northwest on U.S. 69 for four miles and then turn left onto Farm-to-Market Road 1818 for a last little diversion through Diboll, a town that is almost creepily neat and tidy. A huge plume of steam rises from Temple-Inland’s particle-board plant. Rejoining U.S. 59, I head north, back toward Lufkin. Wanting a memento of my trip, I scan the roadside businesses for something unique. Just north of Burke, a collection of carved wooden birdhouses catches my eye, but the traffic sweeps me on toward the malls that cluster around Lufkin. Then I remember my jar of blueberry jam. It’s not much, but at least I have a small piece of East Texas to take home with me.