On an early summer day in 2016, entomologist Jian Duan arrived at a nondescript office building in north Houston to deliver some bad news—and some good. Texas forestry officials had notified Duan a few days before that they’d made an alarming discovery in Harrison County, four hours to the northeast: they had trapped four adult emerald ash borers in a forested area just south of the East Texas hamlet of Karnack. The destructive beetle, which is native to the forests of Russia and northeast China, had previously been detected in the neighboring state of Louisiana, but this was its first sighting in Texas. The bug had jumped the border, and that was exceptionally bad news for the many varieties of native ash trees that call Texas home. State forest officials found themselves in the grips of a full-fledged beetle crisis.

They asked Duan, a research scientist working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Newark, Delaware, to fly down to the Bayou City to give his input. At that time, Duan was quickly becoming one of the nation’s foremost authorities on the emerald ash borer, given his prolific publications on the subject and repeated exploratory trips to Asia to study the insect’s life cycle and natural predators. Inside a conference room that day, Duan shared what he knew and laid out the high stakes. He warned forestry officials they were in for a protracted battle against a creature that had run roughshod over North America forests since being detected in Michigan in 2002, blighting tens of millions of ash trees caught in its warpath. Duan told them how the ash borer had traveled staggering distances, chewing trees all the way, in just over one decade’s time. “I talked about the history of this beetle and the difficulty of managing it,” Duan said. “Basically why, you know, we cannot contain it.”

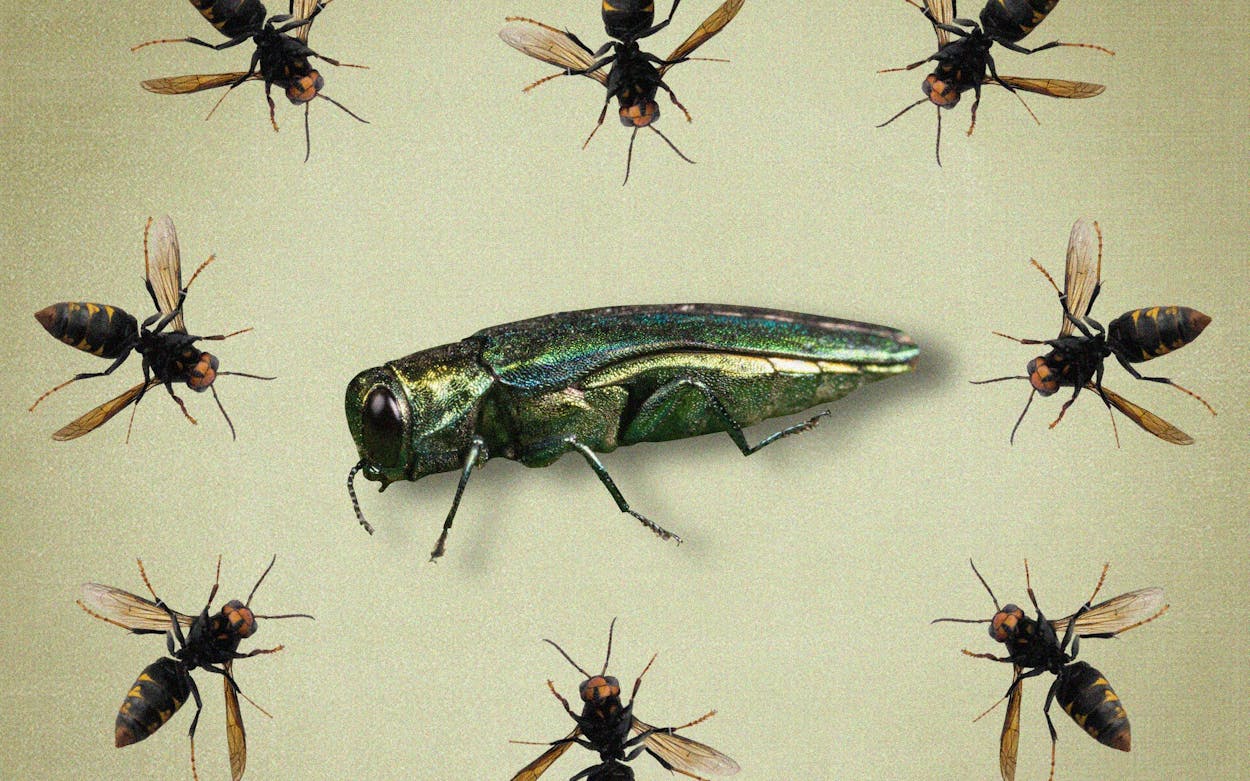

Then Duan gave them the good news: he was working on a solution. While conducting research on the emerald ash borer in Russia and China, he and other researchers found four species of stingless wasps that were its natural predators. All four are able to exploit the tiny crevices and holes—nearly invisible to the human eye—in a tree’s bark, where borers lay their eggs and where the larvae feed. The wasps, which parasitize either the eggs or larvae of the ash borer, appeared to keep them in check in Asia; Duan theorized that the wasps could do the same in the United States. He collected specimens and brought them back home for further study. After getting federal approval, Duan released a small number of the wasps at sites in Michigan; preliminary findings showed that their presence did indeed make a dent in local beetle populations. There was light at the end of the ash borer’s tunnel.

But then Duan had more bad news. He didn’t know whether the wasps would be effective in Texas. The Midwestern climate of Michigan is similar to that of northeast China, so it stood to reason that the wasps would feel at home there. But Duan didn’t know whether they would adapt to Texas as readily. Plus, he still needed to demonstrate that the wasps wouldn’t pose a threat to the state’s native wildlife, an important step in acquiring permission to release a species as a form of biological control. The upshot was that it could be years until Texas got a chance to set the dogs on the beetles, so to speak. “It’s a long process to actually get a permit,” Duan said. “You cannot just collect a bunch of wasps and release them. It’s a very serious business.”

Duan left Houston that day and returned to his office in Delaware to continue his research. Years passed, and just as he’d predicted, the infestation in Texas accelerated. In 2017 the bug jumped two hundred miles from Harrison County to Tarrant, where it was spotted by a ten-year-old boy who submitted a photo to the citizen-science website iNaturalist. The ash borer was detected in the East Texas counties of Marion and Cass the following year. Denton and Bowie Counties were infested in 2020, and then in 2022 the pace ramped up: the ash borer set out on a northwestern route through Texas, popping up in Parker, Dallas, Wise, Morris, Rusk, and Titus Counties. In June of this year, a positive identification was made in Cooke County, on the border with Oklahoma. More are likely to follow. Roughly 5 percent of Texas counties are now infested.

The insect’s widening footprint is a potential death sentence for the roughly 400 million ash trees in Texas’ forests and developed areas. Left unchecked, the ash borer can transform entire neighborhoods, park trails, and wide swaths of forest into barren landscapes. Infested ash trees die from the top down, giving their canopies a ghostly, skeletonized appearance. D-shaped exit holes in the trunk indicate where young beetles have left their nurseries to explore the wide world of tasty, tasty ash trees. Underneath the bark, wood-chomping larvae leave behind a collection of squiggly trails called galleries. The presence of woodpeckers, known to be voracious grub eaters, can also be a sign of infestation.

Ash trees can be treated with injections of emamectin benzoate, an insecticide that kills any ash borers who attempt to feed on the trees. But it’s not a miracle cure. The pesticide wears off after a few years, and the treatments are expensive. The chemical also makes the wood and leaves toxic to other, beneficial insects that need the trees to survive, said Brett Johnson, conservation manager for the City of Dallas. “When you look at your insects and pollinators, there are a lot that are ash specialists in some stage of their life. Now it is poisonous to any insect that’s trying to use that tree,” he said. Roughly one hundred types of insects depend on ash trees at some point in their lives; more than forty arthropods rely on them exclusively. Birds and other predators eat these insects, so fewer ash trees could mean fewer animals overall. Johnson said that between 4 percent and 8 percent of Dallas’s urban forest consists of ash trees, mainly white and green ash. The city hosts one of the largest urban canopies in the nation. Johnson said that the City of Dallas is putting the kibosh on planting ash trees for the next decade or so to prevent new infestations. Workers have deployed traps and treated some trees with emamectin benzoate, but the emerald ash borer is a tough bug to beat. “This has been one of the most challenging issues I’ve worked on,” said Johnson.

At the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, in Austin, an effort to preserve threatened ash trees began in 2012, before the ash borer made landfall in Texas. That year volunteers collected 125,000 seeds from the Texas ash, a species that’s abundant in the area, said Sean Griffin, the center’s director of science and conservation. The seeds were cleaned, sorted, and dried before being stored in freezers inside the facility’s seed bank, home to hundreds of plant species. Griffin said the seeds can not only be used to replace ash trees killed by beetles, but they may also be useful in crossbreeding experiments to make future trees more resistant to the pest. “In a very basic sense, we want to protect these species in the face of annihilation,” he said. As the ash borer infestation picks up in Texas, Griffin said he’s considering reviving the program to save even more ash seeds.

But how did the emerald ash borer get to Texas in the first place? And how did it spread so quickly? Experts say the insect’s rapid spread through the country has been accelerated by humans’ tendency to move ash firewood from infested areas to noninfested areas. One titillating theory is that attendees of NASCAR races have unwittingly spread the pest by bringing firewood from infested areas to campgrounds near where races are held. It’s not exactly a fringe theory: in 2014, forest officials in New Hampshire specifically cautioned NASCAR fans against bringing firewood from outside areas to prevent the insects’ spread. The USDA’s animal-inspection division has also identified NASCAR racetracks as “locations where high-risk facilities or conditions are present and suitable ash trees are located.” Allen Smith, a regional forest health coordinator for the Texas A&M Forest Service, said he’s considered the theory before but hasn’t come up with any conclusive answers. “We looked at it, but we can’t really prove that ‘Hey, this beetle or this spot of dead trees was caused by NASCAR,’ ” he said. To keep people from unwittingly contributing to the problem, he encourages Texans to get local firewood for camping trips. The adage Smith uses: “Buy it where you burn it.”

The Texas Department of Agriculture has mandated firewood quarantines in infested counties to keep the beetle at bay. Experts say these orders have likely slowed its spread, but they haven’t kept the ash borer from annexing ever more of the state. For its part, the USDA lifted its federal quarantines on ash firewood movement in 2021, opting instead to focus on the research Duan and his colleagues are doing on parasitoid wasps. One species in particular, Tetrastichus planipennisi, has proven to be particularly potent in field trials. Duan estimates that without the wasps, ash borer populations would have been two to three times higher, “clearly indicating that the tiny wasp is playing a very effective role in reducing ash borer density rates,” Duan said. Though no site studies have been approved in Texas, releases have been conducted in nearby Louisiana and Arkansas, so there’s hope yet.

Despite Duan’s progress, he said he’s still trying to show his adult children that exciting things can happen in the laboratory. “I keep trying to convince them that I’m doing cool stuff!” he said. Well, if you’re helping turn the tide of the emerald ash borer apocalypse, you’re cool in our book.

- More About:

- Critters

- Houston

- East Texas