Under the right circumstances any fool can catch a bass. So what’s all the fuss about: why are there specially designed bass boats, professional bass fishermen competing on several tournament circuits, slick bass magazines, even unofficial bass-catching uniforms? Why are hundreds of thousands of bass-crazed zealots on their way to replacing golf nuts and tennis bores as objects of bewilderment to their more normally constituted brethren? Because, you see, circumstances are rarely—indeed, almost never—right.

Until quite recently nobody worried about that very much. Bass fishing used to be thought of as a humble avocation pursued mostly by old men and little boys—persons with lots of free time. Either the fish were biting or they weren’t. No big deal either way.

Not anymore. The almost legendary finickiness of the largemouth bass is becoming as important to the mythology of the New South as magnolia blossoms and mint juleps were to the Old. The bass boom is a sure sign that leisure time and folding money are within the grasp of Everyman on this side of the Mason-Dixon line. Men whose fathers struggled to scrape a living out of the red soil have found their life’s challenge in landing a Junker. If bass were easy to catch, then Ray Scott wouldn’t be a millionaire, Tommy Martin would still be making commercial loans in Nacogdoches, and nobody would have heard of Marvin Baker or Ricky Clunn.

Who are they? Well, if you’re a bassin’ man who follows the pro tournament circuit, you already know, in which case I’m very surprised you got beyond the part where I said any fool could catch one; or else it is news to you that Ray Scott is the Hugh Hefner of bass fishing, its number one organizer and merchandiser, and that Tommy Martin, Marvin Baker, and Ricky Clunn are professional bass fishermen, the best hawg busters, as bass experts are called, in the state of Texas.

In the last ten years or so, bass fishing has been transformed from a pastime involving earthworms, minnows, and plastic bobbers into a certifiable American craze, complete with a technology and mystique every bit as complicated, arcane, and expensive as that of sports car racing or Alpine skiing. It is possible to earn upwards of $50,000 a year in prize money and endorsements just for catching fish, not to mention a shot at a syndicated television show. The sport has its own jargon, fan magazines, and legendary figures, and an entire industry has grown up to support it. About all it hasn’t got at this point are groupies, and judging from a couple of spectators I saw recently at the Bass Angler Sportsman Society (BASS) Tennessee Invitational, it won’t be long now. So if your kid prefers to take his exercise sitting down, take heart: he may grow up to be a sports hero yet.

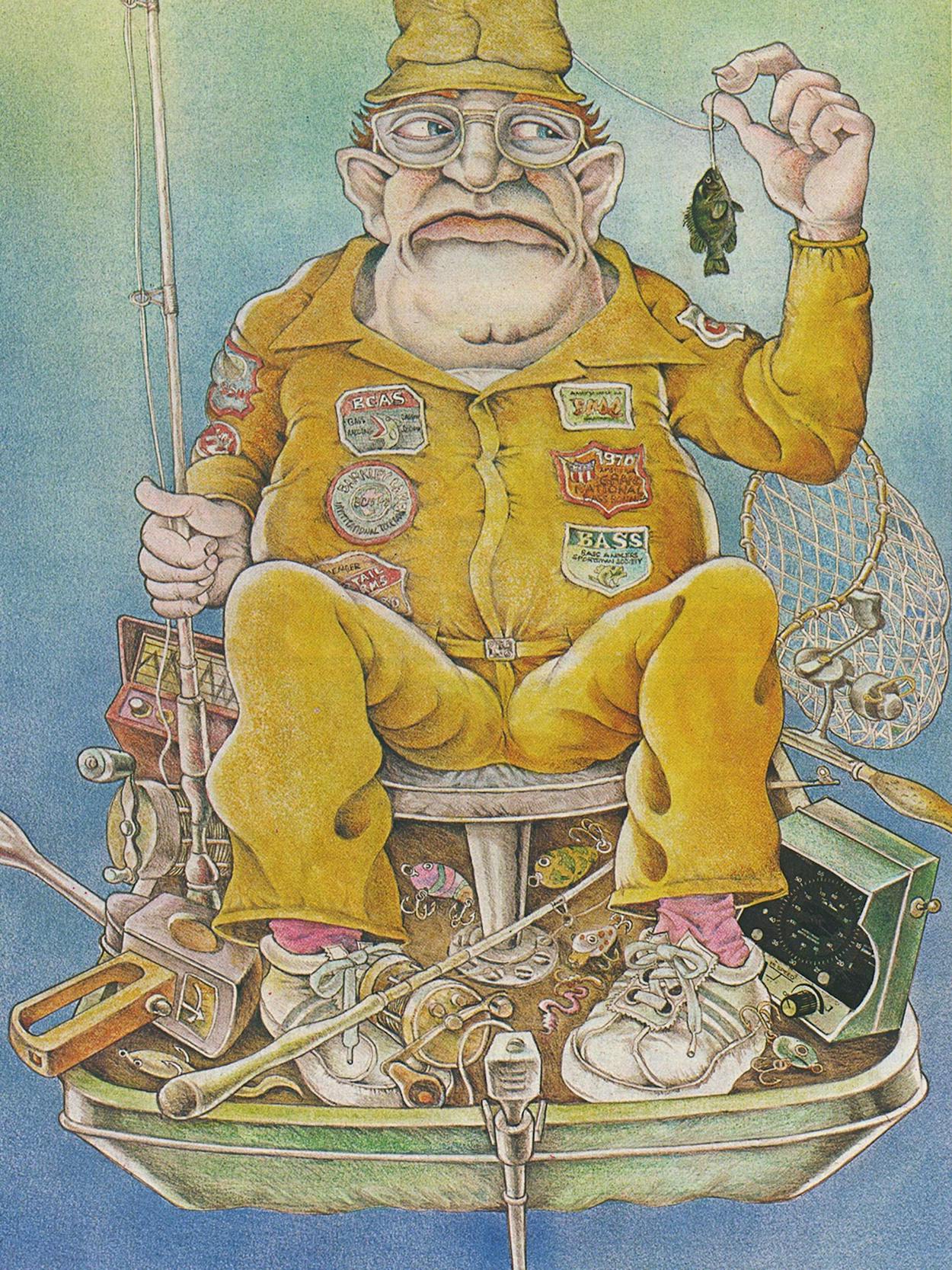

Much more likely, of course, is that he will become a weekend participant and fan, in which case you are well advised to begin planning his financial future immediately. The way things are going, the average basser will soon be spending more per pound for his fish fries than it would cost to have Iranian caviar flown in direct from the Caspian Sea by chartered jet. A true devotee should expect to lay out somewhere in the vicinity of $10,000 just to equip himself to the point where his friends won’t snicker behind his back when he comes out to play. For starters, there is the boat. One does not fish for bass in just anything that will stay afloat. If you’re serious about catching bass, you’ll want a bass boat ($5000 and up), which is equipped with more underwater devices than a World War II submarine and is just about as practical for catching anything other than bass—but then no self-respecting bassin’ man would even consider fishing for another species. Next there’s the unofficial uniform: the well-dressed basser resembles nothing so much as a vacationing fighter pilot in his bright polyester jump suit (preferably yellow or red), dotted with tournament patches resembling Strategic Air Command insignia. He also needs aviator sunglasses and a long-billed cap with an adjustable plastic sweatband. Throw in the usual fishing gear, annual dues to one of the several organizations for bass fishermen, and enough ready cash to haul everything around the countryside in search of Micropterus salmoides, and you’re ready to begin.

The average devotee is about as likely to be a member of the Sierra Club or the Audubon Society as he is to be a Hindu.

Until very recently (future scholars will probably fix the date in 1968 with the first issue of Ray Scott’s Bass Master magazine, published in Montgomery, Alabama), styles and trends in the piscatorial arts used to be set by New York-based publications like Field & Stream and Outdoor Life, which catered, with occasional exceptions, to regional tastes of Northeasterners. Now your average Yankee fisherman, the type who is always talking about “matching the hatch” and buys his equipment from L. L. Bean or Abercrombie & Fitch, regards the largemouth bass as an undiscriminating aquatic lout who hangs around murky, lily-padded water instead of gin-clear streams or pools. A bass is the kind of fish that would pass up a Mayfly or an exquisitely tied and artfully presented Royal Coachman in favor of some unspeakable lump of crudity like a bullfrog or a salamander. Worse, it has scales. If a bass should accidentally be taken, the best thing to do is throw it up on the bank to rot so that it doesn’t stunt the growth of more useful fish. The kind of man who would deliberately angle for bass would pass up scotch in favor of beer or even wear doubleknit suits and white shoes.

Exactly. Bassin’ men tend to be Southern men, white Southern men to be a bit more specific, and in general they don’t anymore care what non-bassers think of their passion than Cale Yarborough worries about the image stock car racing has on the French Riviera. Although bass are found in almost every state as well as in Mexico and Canada, and have for many years been the most popular American game fish, true bass idolatry is a Southern phenomenon. In Texas, the real hotbeds of zeal lie in that part of the state geographically and culturally closest to the Deep South—east of a diagonal between Houston and Fort Worth. Providentially, that is where most of the state’s freshwater lakes are.

Your typical Northern fisherman tends to be an amateur environmentalist; he hikes and camps out and thinks the government ought to be more aggressive about protecting whatever rivers might have escaped the ravages of Consolidated Edison and its ilk. One has but to observe the Dallas Firefighters Bass Club on a hot July afternoon, drawn into a primordial beer-drinking ring on the shores of Lake Sam Rayburn, to realize that if there is one thing bass fishing is not about is a Return to Nature. The men hunker inside a circle made by their machines: boats, campers, heavy-duty pickups, mechanized life-support systems that are probably costing them as much as their home mortgages. The sound of air conditioners and the whine of outboards from a nearby marina drown out whatever birds or insects might otherwise be audible. As usual, the bass aren’t doing squat; nobody is catching anything. The conversation runs heavily to equipment. The average devotee is about as likely to be a member of the Sierra Club or the Audubon Society as he is to be a Hindu. Next to an efficient state program of stocking and managing public waters for the optimum number of lunker bass, all he asks of government is good access roads, fully equipped boat docks, paved launching ramps, and ample parking space for his car and trailer.

In his relationship to his prey, the bass fisherman is more combative than anything else. It is clear from the rhetoric of articles and advertisements directed toward cultists that the large-mouth bass is to be regarded as a he-man fish—a rampant predator who to reach trophy size must survive heavy odds in an underwater free enterprise system that makes Melvin Munn’s Lifeline philosophy sound like parlor socialism. A big bass is called a hawg or a lunker, macho terms whose sexual connotations are matched only by a “honey hole,” which is a place one knows to be frequented by lunkers, and a secret to be shared, if at all, only with one’s most trusted companions. Bassers regard the object of their quest as no beast to be tampered with; one acquaintance of mine, upon being chided for using a 25-pound test line where 8 or 10 pounds would be more sporting, growled, “If you want to be kind to fish, get yourself an aquarium.”

The growth and development of contemporary bass fishing is both a cause and a result of three closely related phenomena. One has already been mentioned—the economic growth of the South to the point that the term “leisure industry” no longer means something like swatting flies in a hammock. The other two are the building of dams and subsequent creation of sprawling freshwater impoundments like Lake Sam Rayburn and Toledo Bend Reservoir in East Texas; and the spontaneous generation of somebody like Ray Scott, a New South entrepreneur of the kind that Izaak Walton could never have imagined.

Ray Scott is the founder and president of BASS and the publisher of Bass Master, a professionally designed special-interest magazine that is mailed out bimonthly to each of the club’s 262,000 members, most of them in the South. A membership in BASS costs $10 annually and judging from Scott’s imitators (among them magazines like Southern Lunker and Fisherman’s Digest, the latter the official publication of the Poor Boy Bass Association, headquartered in Tulsa), the enterprise is turning over a lot more than just subscription money. In a recent copy of Bass Master, which featured national rankings of tournament professionals alongside full-color layouts of large-mouth bass in provocative poses, 54 of the 128 pages were devoted to full-page ads for bassing paraphernalia, a fair amount of which Scott, like his precursor Hefner, sells himself. All in all it is the coziest marketing deal since Tom Sawyer’s arrangement for whitewashing Aunt Polly’s fence. You send Scott $10 and he sends you advertisements for his own enterprises. The editorial content of the magazine runs to pieces like Understanding Graphite Fishing Rods, together with fan mag features on tournament pros like Roland Martin: 1975 Bass Angler-of-the-Year and Jimmy Hustle: Basser-on-the-Go. In many cases the articles are virtually indistinguishable from the ads. One feature lists the top 24 tournament fishermen and tells what they prefer in the way of rod, reel, line, lures, boat, motor, accessories, and lakes. Since most of the pros are sponsored and salaried at least in part by the manufacturers whose products they tout and since Scott and BASS sponsor the most prestigious tournament circuit (and the only one Bass Master reports) the whole thing is a merchandiser’s dream.

What all are they selling? To start with there are bass boats, lavish rigs custom designed and really practical only for catching bass on large lakes. Typically they are equipped with an outboard motor anywhere in size from 85 to 175 horsepower that will do 40 to 70 mph, although one Houston basser I spotted on Toledo Bend had a 385-horsepower V-8 with chrome exhausts. These boats retail for between $5000 and $8000 and with accessories can go much higher. Most come with trailers, electric trolling motors with six forward and six reverse speeds to eliminate paddling, sonar devices for reading lake bottoms and locating fish, padded swivel seats, AstroTurf carpeting, electric-powered anchor winches, aerated live wells for storing the catch, and gauges to measure the water’s temperature, oxygen content, and light intensity at any given depth. Some boats have two, even three, depth gauges along the sixteen- to twenty-foot length of the vessel to detect drop-offs. Many fishermen have installed CB radios. In addition, there are rods and reels (at upwards of $150 to $200 each), of which fewer than three or four for different fishing conditions is considered insufficient, not to mention lures and assorted gadgets for measuring, weighing, handling, and fileting the catch. Live bait like nightcrawlers and minnows are considered beneath the dignity of the serious basser. In Scott’s BASS tournaments such bait is illegal, and contestants are limited to ten pounds of artificial lures.

The “wily Mr. Bass” of fishing rhetoric is only slightly more capable of guile than an earthworm. He ranks on the intellectual continuum about midway between a chicken and a potted geranium.

Despite all this stuff the average Joe Bob’s chances of climbing into his rig on Saturday morning and returning with a string of lunkers varies somewhere between slim and none—even though, as I said at the beginning, sometimes it is almost impossible not to catch the dumb brutes. When they are feeding in shallow water they will fight to impale themselves on your hook the way adolescent young women once struggled over a pair of Elvis Presley’s undershorts. But when they are not shallow and/or not feeding, locating and enticing them onto your line can be as fruitless as offering your own jockeys with you in them to the same girls. Zip. Nada. Hours of work casting and retrieving and nothing to show for it but a headache and a sore wrist.

Before I tell you about my fishing trip with Tommy Martin, who just may be the best bass fisherman in Texas, I suppose I should confess that I can only rarely be persuaded to fish for bass on purpose. Catfish are my preferred quarry. Not only are catfish bigger than bass, but they are much better to eat and a whole lot simpler to catch. Contrary to outdoor magazine propaganda, this is not because the largemouth bass is a clever and worthy adversary. The “wily Mr. Bass” of fishing rhetoric is only slightly more capable of guile than an earthworm. He ranks on the intellectual continuum about midway between a chicken and a potted geranium. Anybody who could be outwitted by a bass probably still believes that Rose Mary Woods erased those eighteen and a half minutes of tape while she was answering the telephone.

A few personal examples may suffice: the first, and until fairly recently the largest, bass I ever caught managed to hook, play, and all but land itself entirely without human assistance of any kind. I’d found an abandoned fishing pole buried deep in a closet at my apartment. I bought a purple plastic bream worm to go with it, the kind of bait that is designed less to catch fish than to separate little kids who don’t like to touch real worms from their Popsicle money—about twenty cents worth of it as I recall. I was 25 myself, but having been raised in northern New Jersey, where the rivers do not exactly teem with edible aquatic life, I was an easy mark. After twenty minutes or so of desultory casting in a Virginia farm pond convinced me that there were no fish in it I left the rod lying on the dock and walked off. Imagine my surprise when I returned the next morning to discover not only that the wind had blown my line into the water but also that the bait had been “inhaled,” as they say in Bass Master, by a two-pound largemouth who by the time I found it was exhausted from trying to swim away with the dock. Ever the sportsman, I carefully untangled the line and braced myself for one of those tail-walking, gill-shaking displays of fighting spirit I’d so often read about in the barbershop. It just lay there on its side. I took it up to the house, cleaned it with the aid of my Joy of Cooking, and ate it for lunch. Expecting something vastly different from the despised Friday night frozen fish sticks of my youth, I was not so much surprised as disappointed: poached, a bass tastes remarkably like a spider web.

Most of my subsequent catches have been of the same variety. I have taken ole bucketmouth on minnows while trying for catfish or crappie, on crickets while looking for bream, and on worms while just idly potting around. My kid caught a two-pounder when he was four years old at high noon off the bank of the Arkansas River in downtown Little Rock on a jig. He’d gotten his line snarled while I was teaching him to cast. So it isn’t cunning that makes bass hard to catch; it’s inconsistency. Go to the deep water, find the bottom, and you’ve found the catfish 95 per cent of the time. Bass, on the other hand, move all over the fool place depending upon approximately 732 variables that only a computer could calculate, but which depend, or so I gather from reading about it, upon air and water, temperature, oxygen content, availability of food and cover, barometric pressure, light, cloud cover, sunspots, the moon, Venus, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and for all I know, Dave Kingman’s ratio of strikeouts to home runs.

Given my ambivalence, the reader can imagine how I felt showing up at dawn on Toledo Bend Reservoir on the Texas-Louisiana border to keep a fishing appointment with Tommy Martin, who is the only Texan ever to have won the BASS Master’s Classic, a tournament of the top 25 competitors on Ray Scott’s circuit that is the closest thing to the Super Bowl of competitive bass fishing. That was in 1974, a year in which he also placed first in the Arkansas Invitational, making him the only person on the tour ever to have won the Classic and a second BASS tourney in the same year. Martin is fourth on the all-time BASS list of money winners with a total of almost $25,000. In 1974 his earnings from prize money alone (including winnings on a now defunct tournament circuit) came to $28,000. Though I am both scoffer and skeptic where the large-mouth bass is concerned, it was hard to discount that kind of record. Deep down I figured Tommy Martin must know a whole lot about bass fishing, and what I feared was that I secretly wanted to learn it. One should never trifle with the elemental passions; men have thrown their lives away for bass.

Martin himself is a case in point. Six years ago he was 29 and an office manager for a Nacogdoches commercial lending company. In addition to a salary that made it possible for him to live quite comfortably, Martin had a company car for his personal use, insurance, hospitalization, and a retirement plan—all the trappings that entice most of us to sell ourselves to bureaucracies and stay put. One thing he didn’t have was enough time for fishing. So he threw it all over and became a fishing guide, first on Lake Sam Rayburn and more recently on Toledo Bend, where he operates out of the Harborlights Marina, about five miles outside the crossroads hamlet of Milam and around sixty miles east of the nearest town of any size, which is Lufkin.

A fishing guide can pursue bass just about any time the inclination strikes him, which had better be pretty often, because even at $60 a day, he is not getting rich very fast. Then there is the cost of his equipment and the num ber of days that the weather is too lousy or there is too much competition from hunting or football and nobody calls. Those are the days Martin tries out new techniques, searches for new locations, or, believe it or not, fishes for fun. Asked how often he does that, Martin, a carefully composed man who gives the impression that he misses very little and keeps a lot to himself, acts surprised. “All the time,” he says. During the warm months he is often on the water twenty or thirty days running for anywhere between eight and twelve hours at a time. For that reason I am inclined to doubt it when another guide confides in me, while Martin brings the boat around, that “I love fishing. Tommy’s in it for the money.”

It would take a genuine grouch or a real adult, of whom I have known two in my life, both female elementary school principals, not to get a certain charge out of taking a bass boat over the hump and whipping through a heavily timbered lake like Toledo Bend at dawn on a summer morning. I don’t own a jump suit and Martin prefers cut-off jeans, but there is something about the two-man hunting team setting out in the gray half light that excites the urge to dress in costume and give the thumbs-up signal to other bassers as we pass them. Had we come upon a cheap aluminum flatboat like mine back home with a couple of wimps catfishing, I doubt that I could have resisted hooting in derision. For this Saturday morning anyway, I was more than a mere fisherman, I was a bassin’ man, and with Martin nearby, I could even pretend that I knew what I was doing.

Although he is no doubt aware that his livelihood depends upon it, such childishness would probably embarrass or irritate Martin. On the water he is a professional; as in every form of human endeavor I know anything about, the difference between success and mediocrity in bass fishing is the ability to concentrate. Tournament bass fishing, Martin says, is roughly 80 per cent skill and 20 per cent luck. If we were fishing a tournament here, he would expect to catch the tournament limit of ten fish and more, culling the smaller ones and bringing in the ten heaviest to be weighed, which is how tournament winners are determined. The luck comes in the occasional big fish that can make the difference between being in or out of the money. And even that is not entirely up to fortune, Martin says; there are ways of locating and fishing for the big ones.

I am skeptical. Nobody catches a limit of anything with me in the boat. I talk too much, fidget, get bored. Sometimes I wonder if fish can smell my breath, my underarms. There are acquaintances of mine who would sooner go whitewater canoeing with a Saint Bernard puppy than angling with me. By the time the sun is high enough to cast a shadow, my predawn euphoria is gone. I have driven halfway across Texas to sit in the sun and put the curse on a perfectly decent fellow whose only fault seems to be his overconfidence.

The fish give a quick tap and they are gone; I am missing more strikes than a one-eyed umpire with a cataract.

All the while Martin is crawling his plastic worm across the bottom in seventeen to twenty-five feet of water along submerged creek channels and drop-offs that he locates by consulting his depth finder. Anybody who uses anything but plastic worms this time of year, he says, is wasting his time. Cast and retrieve: for me the operation is repetitious, mesmerizing; for Martin it is not. He is cool and systematic. After fifteen or twenty minutes at one spot he cranks up the motor and we move to another. “If they aren’t in here by now, they won’t be,” he says, squinting at the lingering cloud cover. “We’ll try a little shallower.” At the third or fourth spot he catches his first bass, a two-pounder. In the next couple of hours he will boat fourteen fish, all between two and three and a half pounds. Astonishingly enough I catch four myself after some instructions on how to set the hook properly with a plastic worm. The fish give a quick tap and they are gone; I am missing more strikes than a one-eyed umpire with a cataract. Martin, however, can give instructions, answer my questions fully and politely, and still seem to have the most sentient part of his mind down there on the end of that line, creeping over stumps and weed beds in the murk of seventeen feet of muddy water, just waiting for a lunker bass to make his ravenous charge.

In spite of his choosing to live where he does, Martin is not a rural type at all. A native of Texas City, when he got strapped for cash last winter he went back for a few weeks and got a job installing industrial insulation. What he admires most are people who know how to do things and live by their native wit. After beginning tentatively so he won’t risk offending a client, he discusses his admiration for Muhammad Ali as a man who knows how to make the best of what he’s got. In his spare time Martin plays pool and Ping-Pong. I had the distinct impression that one might take a game or two from him at first but would be ill-advised to put any money on repeating. Of his decision to give up the security of his office job for guiding and tournament fishing he is matter-of-fact. Anybody who really wants to can put together a living, he thinks. The only way to fail is to lack imagination; nobody has to do something he doesn’t like. Although he has been offered a job by a friend in the salvage business at $40,000 a year, he says he prefers to keep fishing as long as he can make around half that, which is just about what he averages. Asked about retirement, he shrugs: “I think about it once in a while, but I see lots of old dudes around sixty-five or seventy out here guiding.”

Not much figuring is required to determine that a guide charging $60 a day would have to fish virtually every day of the year in order to gross $20,000, let alone show a profit after expenses. That is where the tournament circuit comes in, although not quite in the way one might imagine. Although the winner’s check for one BASS event might be in the vicinity of $5000, depending upon the number of contestants entered, a competitor fishing in all six tournaments qualifying him for the Classic would barely make back his expenses each year even if he could count upon placing first at least once each year. With 200 to 250 entrants in each tournament and prize money dropping rapidly from the top (second place brings less than $2000), the odds are very great against having a year like Martin’s in 1974. Even Bill Dance of Memphis, the television sportsman who is second on the BASS list of all-time money winners, has not won a tournament since 1970, although he enters nearly all of them and is one of the legendary figures I spoke of earlier. In order to compete, a man like Tommy Martin has to take off from his regular guiding business for a week or ten days, drive as far away as Virginia or Florida with boat in tow, put himself up in a motel, and pay the $250 entry fee. If he had to foot the bill himself, fishing tournaments would make no economic sense at all. Even though Martin is having a very good year from the standpoint of consistency and is, as of this writing, fourth in Classic “points” among all contestants (which I will explain momentarily) he has won under $2500 in prize money, a sum that comes nowhere near matching his expenses.

But Tommy Martin doesn’t pay his own expenses. The Rebel lure people do that, besides paying him a retainer as a consultant in equipment design. His boat and trailer are provided by Bass Cat boats, his depth finders by the Ray Jefferson Company, and so on. The only items of fishing equipment Martin owns that he paid for himself are a couple of reels. As long as he can stay ahead of the crowd as one of the top 25 or 30 competitors on the BASS circuit, Martin can afford to fish for a living. For the ordinary fisherman, though, there are no such benefits. What he looks forward to is the company of similarly minded men who view a tournament more as a fraternal gathering and an opportunity to keep up-to-date on the latest techniques than as a sporting event. It is the chance to meet and talk with fellow bass fanatics, plus the possibility of drawing one of the stars as a fishing partner, that motivates the vast majority of anglers who enter BASS tournaments without having a prayer of winning.

Besides the economic impact of Bass Master, the excellent press coverage and the $25,000 top prize for winning the annual BASS Classic, Martin and other pros like to fish Ray Scott’s tournaments because they are well run and honest. Cheating at local or club tournaments is a fast way to make off with anything from trophies and bragging rights to several thousand dollars. The organizers of one-shot competitions offering exorbitant prize money are often suspected of chicanery, apparently for good reason. A fishing tournament is very easy to fix. Martin claims he has seen fish weighed at some tournaments that look as if they had been frozen for at least a year. Doubtless there is more than one lunker out there which has been weighed almost as often as a butcher’s thumb. Commoner and more difficult to detect, however, are shady practices like contestants pooling their catch or staking out wire-mesh baskets of fish in hidden coves to be gathered when nobody is looking. One competitor has been banished for life from the BASS circuit for the latter tactic and another suspended for not reporting him. The winners of all BASS events are now routinely given, polygraph tests as an added protection.

In order to get a firsthand look at the pros in action, I traveled to Gainesboro, Tennessee, about 75 miles east of Nashville, for the Tennessee Invitational, the fifth of six BASS events leading up to the 1976 Classic. By this time my successful trip with Martin had gotten me started on a mild case of bass fever, and I was ready not only to recant my previous heresies, but also to wonder about the manifold possibilities in combining a dual career of freelance writing and tournament fishing. I already had a typewriter, I reasoned; all I needed was a bass rig. Then came Cordell Hull Reservoir.

By the fifth tournament of the year, BASS is having some difficulty in attracting a full field of 250 contestants. Only the top 25 point winners from the preliminary tournaments will qualify for the Classic, held each October on a “mystery lake” that is not announced until just before the event. The contestants themselves are airborne in a chartered plane before they are told where they are going. About fifteen of those spots are already locked up by men who have done well in the earlier meets. Tommy Martin, for example, was in third place with 154 points going into Cordell Hull. With points awarded on the basis of 50 for first, 49 for second, and so on, Martin had averaged a twelfth place finish for the first four tournaments. Only 14 points behind, the leader, Martin was (and still is) very much in contention for the BASS Angler-of-the-Year award given the top qualifier. Other Texans in contention—Marvin Baker of Broaddus and Rick Clunn of Montgomery, ranked twenty-sixth and fortieth respectively—needed to do well here to have a shot at qualifying for the Classic. Persons much further down in the standings than Clunn had little chance, barring a miracle finish. Accordingly, the BASS staff writers had pulled out the rhetorical stops in a heated display of icthyopom that lured contestants from 26 states to Cordell Hull, which “starts producing bass by the wagonloads in July,” and where “the weather is always nice—it’s only the bass that get hot in July in Tennessee.”

Now anybody who is capable of taking that last claim on face value deserves anything he gets, and for the tournament week he got it. Afternoon temperatures hovered between 95 and 100 degrees, which is about what the thirteen Texas entrants could have expected had they chosen to stay home—but what about the lone entries from Vermont and Minnesota? To make matters worse, the two dams upstream picked that time to flood the impoundment with millions of gallons of water at 45 degrees, creating water conditions more suitable for muskellunge or salmon than bass. The meeting of cold water and hot air produced a surface fog so dense in places that it looked as if the heavens had opened up a cascade of dry ice. On the first day of the three-day event, not one entrant caught his limit of ten fish. Junior Samples of Hee Haw fame did what most contestants with his bank account would have done and went home to Georgia. Tommy Martin weighed in one keeper at two pounds three ounces. Only Rick Clunn, who guides on Lake Conroe when he isn’t tournament fishing, seemed to have things figured out. Whatever Clunn was doing out there brought in eight fish weighing in at more than seventeen pounds and put him so far ahead that many of the sportswriters were prepared to concede him the championship.

Unfortunately for Clunn, however, his technique quit working the next day. He managed one two-pounder in ten hours of fishing, but no one else did much better, so he retained the lead. Martin, battling a fever and headache as well as the heat, caught no keepers at all. Some of the fishermen began to complain that there were hardly any fish in the lake, that the site had been badly chosen. A rumor circulated that Ray Scott was privately peeved; he had ventured his opinion, so the story went, that there were more good bass in one acre of Toledo Bend than in all of Cordell Hull. But Scott showed no sign of distemper at the weigh-ins, where, resplendent in a white jump suit with BASS insignia, white cowboy hat, sunglasses, and open-toed sandals, he kept up a nonstop carnival pitch for the several hundred fans who sat sweltering in open bleachers. “Here comes Roland Martin, folks, of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. Now this here is some kinda fisherman. Winner of eight BASS tournaments, 1975 BASS Angler-of-the-Year award. Say howdy to the folks, Roland. What you got there? . . . Two fish? Boy, I tell you. It’s tough out there. The day Roland Martin catches two fish, that’s a tough day. Tell the folks what you got ’em on, Roland.”

It gets even tougher on the third day. The weigh-in is conducted in a parking lot adjacent to the marina. As fishermen pull in they are given plastic bags for their catch, which they fill with water as well as fish. Extra points are awarded if the fish is alive; all fish are dipped in a solution to prevent their being infected, then dumped in a tank. They are returned to the lake as soon as possible. The BASS motto is “Don’t Kill Your Catch.” But today fewer than half the contestants bother to weigh in at all. Boat after boat comes in empty. Those who do have something to weigh come up the steps from the marina to the scales trying not to look foolish with one, two, at best, four fish. Tommy Martin gets skunked again. He has driven sixteen hours to get here, scouted the lake for three days, fished for three more, and caught one fish large enough to keep. He has a cold. It is now 6 p.m. Friday. He is due back in Texas to take a client fishing at 5 a.m. Sunday. His car is blocked in and he can’t leave. I figure he has got to be sick of fishing, that he will stay in Nashville, take in the Grand Ole Opry, and call in sick. “Shoot no,” he says.“That’s just the way it goes sometimes.”

Scott’s patter goes on: “Ladies and gentlemen, here comes Woo Daves from Virginia. Woo entered one tournament on his home lake last year and won it. Lotta people thought it was a fluke, but this year ole Woo’s doing all our BASS tournaments and showin’ ’em how. That’s a nice fish there, Woo. Tell ’em what you caught him on.” Woo explains he got that big one with this Little Scooper lure, which he produces from his pocket and dangles in front of Scott for the crowd’s inspection. “Yes-sir,” Scott replies, “I believe I’m gonna get me one of them little dudes.” A TV cameraman standing next to me who says he used to fish the BASS tournaments back when the entry fee was just $100 spits on the ground. “Hell,” he says, “that boy hasn’t had that damn bait out of his tackle box in two months. He works for the people that make ’em.”

In the end Rick Clunn does not hang on. He comes in with less than four pounds on the last day and is edged out by Wade Reed of Zwolle, Louisiana, just across Toledo Bend from Tommy Martin’s place. Reed works on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico and drives 400 miles to get home so he can live on the lake. He caught the fish that took him over the top on a dollar lure his wife picked up off a bargain table at K-Mart the evening before. Everybody gets a big laugh out of that. Clunn comes in second, pays for his trip, moves closer to a Classic spot with 49 points, and gets a good chance to push Glastron boats to the sportswriters. It’s good for his guide business back in Texas, he says, because people will hire a celebrity even if they don’t know whether he can guide.

Had he won, Tommy Martin would have been able to replace his 1974 Ford station wagon, which now has over 80,000 miles on it from hauling a boat all over the South. That will have to wait. Had the tournament produced a mess of lunkers, a contestant named Ledbetter tells me, the owner of the Roaring River Marina where the weigh-in was held, “would have had to beat the bass fishermen off with a stick.” But with none of the professionals catching a limit in three days of trying and the winning total reaching only 23 pounds, he is probably in for some hard times. Marinas have been bankrupted by bad tournaments like this one.

As for me, I am considerably chastened by the experience and am rethinking my decision to turn pro. I spent most of my time in Tennessee holed up in a motel room with the flu, eating aspirin, wondering if I’d survive until the weigh-in and half hoping I wouldn’t. Flying home over the route I know Tommy Martin is driving, I am weak, unsteady on my legs, and much disillusioned. I am halfheartedly browsing through a copy of Outdoor Life when I encounter a beautifully illustrated piece on how to drive large-mouth bass wild with a new kind of tandem spinner arrangement rigged with a trailer hook. On the page facing the text an enormous lunker is shown zooming from behind a submerged stump with its mouth open wide enough to swallow a Houston telephone directory, gills flared and a fanatic gleam of mingled rage and hunger in its eyes. It is going to bust that tandem spinner so hard it might just pull the fisherman overboard. Astonishingly, almost against my will, I feel my throat start to get dry. My chest begins to tighten and a wild, unwanted thought begins to dominate my senses. I can barely whisper it to myself: I want to go fishing. I want to catch an eight-pound bass.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- Longreads

- Fishing