WHEN WE WERE DOPEY COLLEGE kids—before we encountered the scary world of careers and children—we measured ourselves against giants and made plans to shake the earth and leave great footprints in our wake. But time inevitably trumps youthful bravado and dreams go unclaimed. How does each of us deal with that dark night of the soul when reality forces us to measure ourselves not by our potential for greatness but by our actual failures? That question is foremost among many that Tim O’Brien poses in July, July (Houghton Mifflin), his stunning novel about an emotionally charged reunion of the Darton Hall College class of ’69. Feelings run high—fueled by strong drink, stronger memories, and the occasional application of controlled substances—as the revelers invest three days of their lives reviving dormant passions and redefining old relationships.

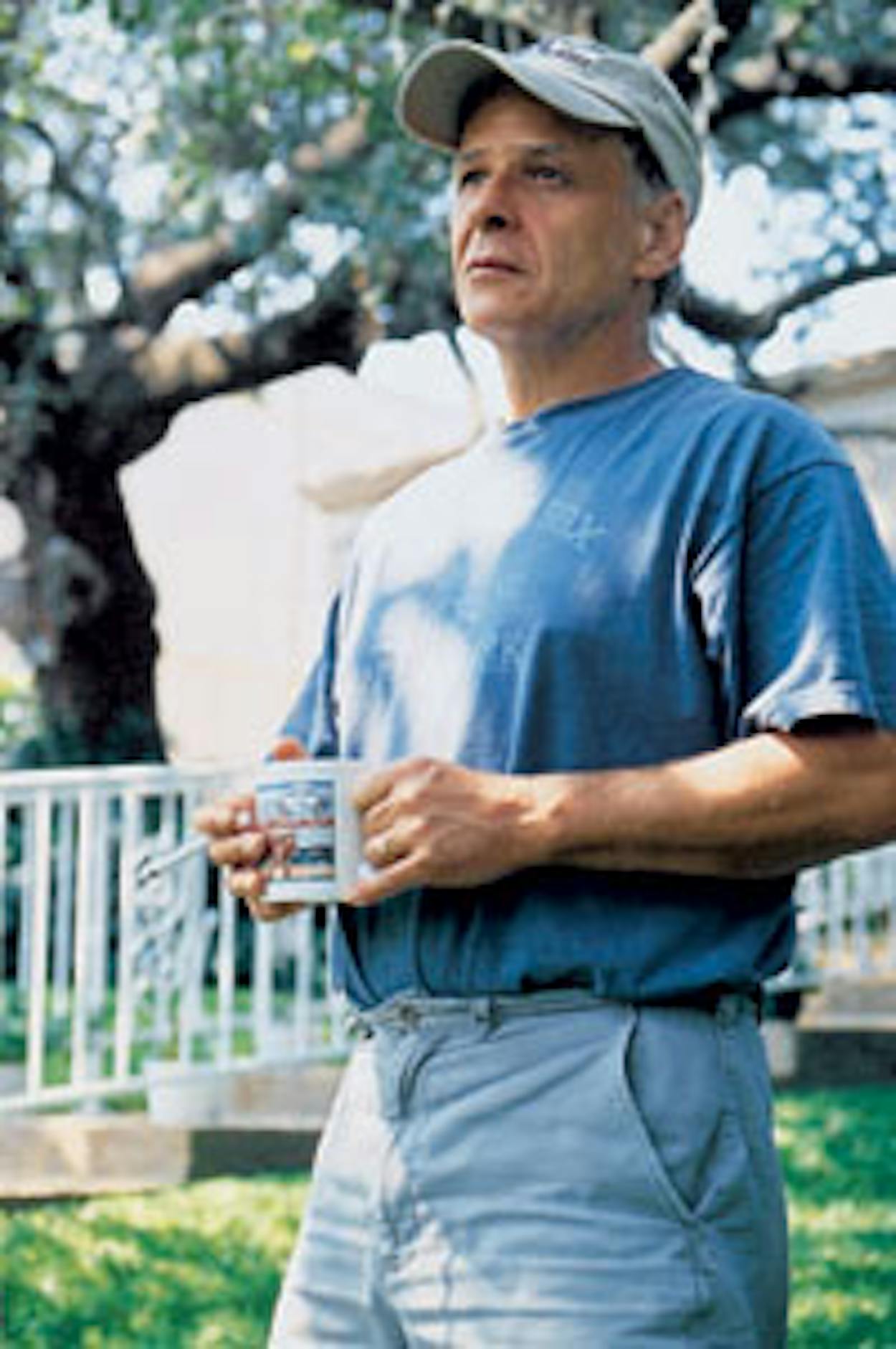

O’Brien, who is 56, wrote July, July in Austin, where he has lived since leaving Boston in 1998 to assume the Mitte Chair in Creative Writing at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos. Before moving to Texas, he feared that the worst stereotypes would prove true and he would find himself mired in a cultural backwater, but he now fervently declares Austin to be “three times more sophisticated than Boston.” He and his wife, Meredith, who is active in the local theater scene, are planting roots; his chair at Southwest Texas is open-ended, and he intends to remain for the foreseeable future.

July, July is a radical departure from its predecessor, Tomcat in Love, the farcical memoir of a pathetically inept college-professor Lothario, which was entirely unlike its predecessor, the politically and historically charged murder mystery In the Lake of the Woods. O’Brien has made it a point to devise different structures for each of his eight books (seven novels and a memoir), an exercise of sorts to keep his writing fresh. July, July was especially challenging, since the large ensemble cast required weaving a dozen individual stories into a seamless whole. Each character had to mature from college age to middle age and arrive at a believable juncture in his or her life.

O’Brien has never been a quick writer; he spends an average of four years on each book. But his painstaking craftsmanship pays off in wonderfully economical prose. Who doesn’t recognize this coed from his or her own college days? “Jan Huebner had been an English major at Darton Hall, a B student, a dorm counselor, a confidante of pretty girls, a Saturday-night bridge player, a chain smoker, a clown. Until her senior year she had slept with no one at all.”

Though O’Brien served a tour of duty in Vietnam and made his literary bones writing about the conflict in Going After Cacciato (which won the 1979 National Book Award and is to Vietnam what Catch-22 was to World War II), both Tomcat in Love and July, July show how far his talents stretch beyond the “Vietnam writer” tag that has been applied to him since early in his career. Which is not to say that Vietnam doesn’t play a significant role in his latest novel. O’Brien freely admits that his experiences in Southeast Asia made an indelible impression that will always influence his writing. And it would be dishonest to write about the class of ’69 without invoking the bloody conflict that divided it, and all of America, into camps—hawks and doves.

July, July opens in the year 2000 in the gymnasium of Darton Hall College, where the class of ’69 has convened for the welcoming dance of its thirtieth reunion, one year late due to the underdeveloped organizational skills of the “turn on, tune in, drop out” generation. Jan Huebner and Amy Robinson, both 53, divorced, and sot-faced from a bottle of vodka they liberated from the bar, set the tone for events to come as their conversation quickly segues from hasty expressions of grief for a recently departed classmate to their need to get laid. Preferably that very night. If not sooner.

As more classmates are introduced it becomes apparent that this coterie of ten friends (not counting Karen Burns and Harmon Osterberg, the two deceased classmates whose ghosts haunt the proceedings) has not been particularly lucky in love. Their group includes five divorcés, one spinster, one widower, and the category-defying Spook Spinelli, whose bigamous lifestyle does little to impede her promiscuity. Careerwise they’ve fared somewhat better, though their professional successes don’t make up for their personal disappointments.

These educated middle-aged adults are baffled by the trajectories of their lives. Marv Bertel has made a fortune from his Denver mop-and-broom factory, but he remains the same unhappy buffoon he was in 1969; only his tailoring has improved. Draft dodger Billy McMann has built a comfortable life in Winnipeg, but he remains inconsolably bitter that classmate Dorothy Stier reneged on her post-graduation promise to jump to Canada with him, failing to show up at the airport on the appointed day. One by one the classmates’ stories are told in flashback (chapters alternate between July 1969 and July 2000, hence the title), and they wonder how their lives went so terribly off course without their consent; how they became their parents or, worse, the failures their parents surely predicted. They were not the captains of their destiny after all, and now they’re just trying to make port before nightfall.

The storytelling is compelling and the subplots are inventive and entertaining enough to carry the book, but the engaging characters are what really drive this narrative. O’Brien advances the novel by finding a flash point for each individual—a single moment from which there was no turning back. For Vietnam vet David Todd, it was his nineteenth day in country, when he alone survived an ambush on his platoon at the Song Tra Ky River; he lost a leg and gained Johnny Ever, a voice in his head that accompanies him everywhere. For Marv Bertel it was a decision to diet his way to a normal size; overly impressed with his new slender self, he jettisoned his wife and, in a ridiculous attempt to impress his young, stylish secretary, fabricated the lie that he was not just a mopmaker but in fact world-famous author Thomas Pierce. Each episode adds detailed strokes that flesh out a group portrait of this angst-ridden Gang of Ten.

This is a big book—sprawling is perhaps a better word. It’s as wide as the political gulf that separates straitlaced expatriate peacenik McMann from dope-addled ex-warrior Todd. It’s as deep as the moral divide between the libidinous Spinelli and the Presbyterian minister Paulette Haslo, who can’t find the fuse to ignite passion in her life. And it encompasses both faithless Marla Dempsey, who waved good-bye to her husband one Christmas Day as she rode away on the back of another man’s motorcycle, and Republican trophy-wife Stier, who dutifully (but unhappily) plays second fiddle to her husband’s automobile obsession. But complex as July, July might be, the author skillfully manipulates the story lines and characters until he arrives at a result that feels both satisfying and true. His writing reflects life as we live it: Comedy collides with tragedy and reality results.

What O’Brien has given us is neither an obituary for the Woodstock generation nor an ode to its ragged glory. He has simply paused on the cusp of the millennium to ponder how the passage of thirty years has changed a group of friends and their world. He finds that life’s daily grind has silenced the fiery rhetoric of their youth and replaced it with talk of “liposuction and ex-husbands”—and that a conscientious objector and a careless soldier can both be casualties of the same unpopular war. July, July is 322 pages of God and mammon, sex and love, war and peace, faith and dishonor, laughter and tears. Tim O’Brien is one of the defining American novelists of our times, and this is his masterwork.