BY DEFINITION, high school kids are idiots. If you’ve but one lonely, honest bone in all of your body, you’ll admit that there was no other time in life when the disparity was greater between what you thought you knew and what you actually did know. Add to that the abject insecurity of untamable adolescence, the body and soul itching to lay claim to their place in the world but possessing none of the know-how to do so, and the result is an idiot. A high school kid is a misfit intent on masking that zit-ridden impotence behind a two-beer buzz and the right kind of car, clothes, and music—played as loudly as your parents and the cops will allow. One of the most beautiful things about growing up is that with sufficient distance, you can see clearly the central mystery of those awful, awkward years: In the attempt to forge your own identity, you did everything you could to fit in.

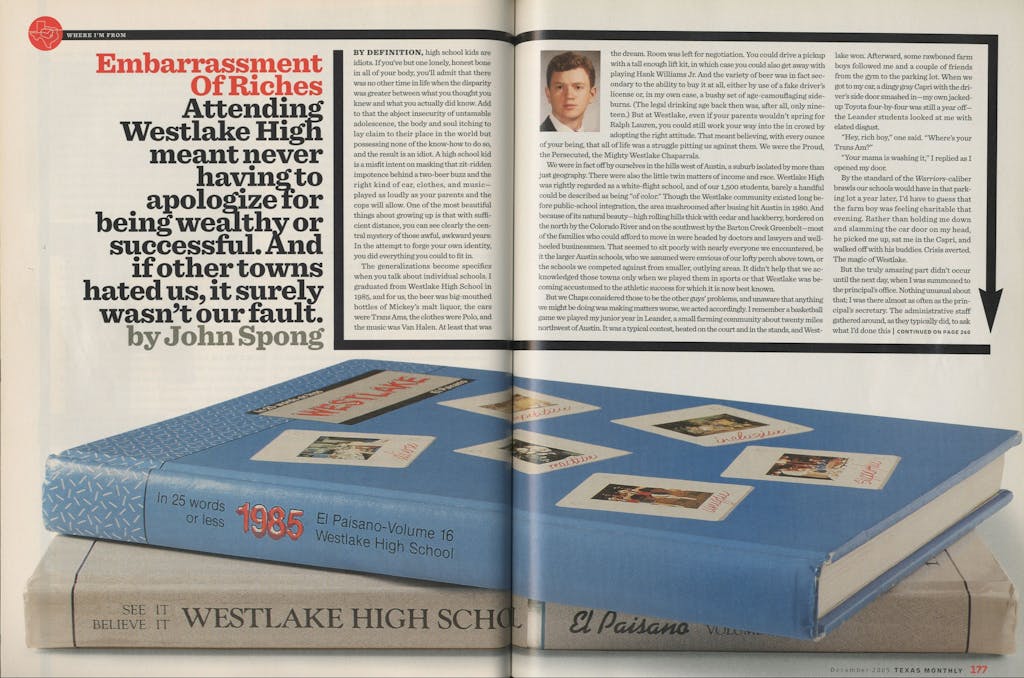

The generalizations become specifics when you talk about individual schools. I graduated from Westlake High School in 1985, and for us, the beer was big-mouthed bottles of Mickey’s malt liquor, the cars were Trans Ams, the clothes were Polo, and the music was Van Halen. At least that was the dream. Room was left for negotiation. You could drive a pickup with a tall enough lift kit, in which case you could also get away with playing Hank Williams Jr. And the variety of beer was in fact secondary to the ability to buy it at all, either by use of a fake driver’s license or, in my own case, a bushy set of age-camouflaging sideburns. (The legal drinking age back then was, after all, only nineteen.) But at Westlake, even if your parents wouldn’t spring for Ralph Lauren, you could still work your way into the in crowd by adopting the right attitude. That meant believing, with every ounce of your being, that all of life was a struggle pitting us against them. We were the Proud, the Persecuted, the Mighty Westlake Chaparrals.

We were in fact off by ourselves in the hills west of Austin, a suburb isolated by more than just geography. There were also the little twin matters of income and race. Westlake High was rightly regarded as a white-flight school, and of our 1,500 students, barely a handful could be described as being “of color.” Though the Westlake community existed long before public-school integration, the area mushroomed after busing hit Austin in 1980. And because of its natural beauty—high rolling hills thick with cedar and hackberry, bordered on the north by the Colorado River and on the southwest by the Barton Creek Greenbelt—most of the families who could afford to move in were headed by doctors and lawyers and well-heeled businessmen. That seemed to sit poorly with nearly everyone we encountered, be it the larger Austin schools, who we assumed were envious of our lofty perch above town, or the schools we competed against from smaller, outlying areas. It didn’t help that we acknowledged those towns only when we played them in sports or that Westlake was becoming accustomed to the athletic success for which it is now best known.

But we Chaps considered those to be the other guys’ problems, and unaware that anything we might be doing was making matters worse, we acted accordingly. I remember a basketball game we played my junior year in Leander, a small farming community about twenty miles northwest of Austin. It was a typical contest, heated on the court and in the stands, and Westlake won. Afterward, some rawboned farm boys followed me and a couple of friends from the gym to the parking lot. When we got to my car, a dingy gray Capri with the driver’s side door smashed in—my own jacked-up Toyota four-by-four was still a year off—the Leander students looked at me with elated disgust.

“Hey, rich boy,” one said. “Where’s your Trans Am?”

“Your mama is washing it,” I replied as I opened my door.

By the standard of the Warriors-caliber brawls our schools would have in that parking lot a year later, I’d have to guess that the farm boy was feeling charitable that evening. Rather than holding me down and slamming the car door on my head, he picked me up, sat me in the Capri, and walked off with his buddies. Crisis averted. The magic of Westlake.

But the truly amazing part didn’t occur until the next day, when I was summoned to the principal’s office. Nothing unusual about that; I was there almost as often as the principal’s secretary. The administrative staff gathered around, as they typically did, to ask what I’d done this time. Only on this occasion, they already knew. “Tell us what you said last night to that guy in the parking lot after the game,” one of them said. So I told them, anticipating more d-hall hours added to what I already owed. But everyone just laughed. “Way to stand up for the school,” someone said. One of them pumped her fist in the air. Then they sent me back to class.

That was Westlake or, as the bumper stickers sold by the booster club read, “The Pride of the Hills.”

MY DAD DID NOT like Westlake even one little bit. He was a Carter-Mondale-Ferraro man, a way-left-leaning Episcopal priest who had a special facial expression he saved for when the subject of my high school came up. It resembled the faces of his Southern Baptist counterparts when they saw two dudes French-kissing. My dad didn’t feel at home in Westlake, and at bottom he had good reason. There weren’t many people living there on a preacher’s salary unless they ran a church in the area. That we could afford to live in Westlake at all was a testament to my mom’s good business sense and the fact that both my parents worked. The Rev, as I liked to call my dad, taught at a seminary and ran a counseling practice, helping people through divorce and death and all manner of spiritual and emotional upheaval. My mom was a full-time nurse who worked nights at the state hospital. By day she sought bargains, her most notable find being a four-bedroom house in Westlake that she and my dad bought for a song and moved me and my two younger brothers into in 1978. But as my dad frequently pointed out, this was before Austin started busing kids across town. He said that if he’d seen the white-flight flood coming, we would have stayed put in North Austin. There was an implication in the move he could never abide.

But it was the materialism he perceived that rankled him most. He and my mom both grew up in families that weren’t alerted to the end of the Depression as early as the rest of the country. My dad’s dad died in 1943, when the Rev was just nine, and the old man’s $8,000 life insurance policy had barely covered his hospital bills. When my dad’s mom was forced to shift from housewife to breadwinner, her eighth-grade education wasn’t much help, and their home in Charlotte, North Carolina, remained simpler than simple. My mom grew up in Ellenwood, Kansas, a small farm town that I’ve never heard mentioned outside our family. Her father, my granddad Ralph, lived to be 78, residing until the end in the same log cabin where he raised my mother, across a dirt driveway from the wheat fields he worked but never dreamed of owning. As I recall from childhood trips to Kansas, their extravagances ran to doilies in the cabin and a welding torch in the barn.

Strangely enough, for decades Westlake’s social standing had not been too different from that. It had always been considered the outskirts of town, home to cedar choppers and university professors, the one because that’s where the cedar was, the other because that’s where the college students weren’t. There was one road from town, which wound through the woods and crossed to the river’s west bank, and Austinites who made the drive saw only dope smokers’ shacks tucked in the brush. The area then was probably best known as home to the Soap Creek Saloon, an even earthier contemporary of the Armadillo World Headquarters and a favorite stage for Willie Nelson, Doug Sahm, and the rest of the cosmic cowboy bunch.

The first schoolhouse had been built there in 1874. That original structure, Eanes School, burned down in 1892, but its replacement was built in 1896 and was still in use in the mid-seventies. Well before Westlake High opened, in 1969, the area had grown enough that Eanes served only elementary-school students, and older kids were shipped across the river to Austin High. But with the completion of the high school, and five years later a middle school, Eanes broke off from Austin and formed its own school district. It’s worth noting that when the Westlake High forefathers were choosing an appropriate nickname for the new high school, the close runner-up to Chaparrals was Cedar Choppers.

Inside the schools, out of view of Austin proper, Westlake was well on its way to earning a new reputation when my family got there. I was in the fifth grade, and the school I’d left was the only one I’d ever attended. My friends had been people I’d grown up with, and there had never been any consideration of what or who was cool. Westlake was different. You only needed that first day in the lunchroom to see that there were tables you wanted to sit at and others you didn’t, and you had to be invited to join the right one. That’s probably the kind of revelation any kid has when he starts a new school. But in Westlake, all the kids knew it. My first day there, a sixth-grader asked me if I’d been popular where I’d come from, a question that would have puzzled me if I hadn’t been so undone by his first query: “Are you a guy or a girl?” I was still contemplating a haircut and burning my white Toughskins when he got to the more important point.

Clothes mattered in a way that was altogether new. I’d always known, of course, what an alligator was, and I had a vague idea of what a polo player looked like. But I had no hint of how much it mattered to have one or the other stitched on your shirt or that there was a pecking order to the worth of those labels: Izod alligator, good; Polo pony and mallet swinger, better; JCPenney fox, you can’t sit at our table today.

The coolest kid in the school had one of those names that preordain junior high greatness: Dallas Allison. He was a head taller than everybody else and, despite being dramatically pigeon-toed, was by far the best athlete. He was so admired, in fact, that instead of being teased about his feet, he inspired half the guys in the grade to ape his walk, myself included. Between classes, the halls swarmed with boys who looked as if they were walking with swim fins on. But that was as far as the imitation went. Nobody could pitch or rebound like Dallas, and once he got his hardship license and started driving a maroon Porsche 924 to school—in the eighth grade—the cool gap widened.

Our envy of Dallas probably helped set the bar on our own expectations unreasonably high. If it had been only us kids confusing our wants with our needs, the Rev might have chalked it up to the muddied priorities of youth. But as Westlake’s ranks absorbed the offspring of Austin’s upwardly mobilizing professional class, the faculty came to expect such investment. When I got to high school, I sang in the ninth-grade boys’ choir. It wasn’t quite the social stigma one might expect; our honors choir perennially received perfect scores at state competition, and the student body was genuinely proud of all the school’s victories. But the choir director told me that for our performances, I’d need to buy a tuxedo. He explained it with a phrase—“Everyone has one”—that I tried to convince him had regularly failed to impress the Rev and my mom. Sure enough, when I passed the tux requirement on to the Rev, he made that familiar face and then seethed, “There are no fifteen-year-old boys who sing so well that they need a tuxedo to do it in.”

AS CONSCIOUS AS WE WERE of what one another had, we paid no mind to anyone else. Our only meaningful exchanges with other schools were at athletic events, where our opponents’ purpose was merely to be ground down and beaten. But we meant much more to them, becoming the most hated rival of every school we played. Our enrollment was too small to play against the Austin schools, so our district opponents were scattered around Central Texas, in small towns like Taylor, Georgetown, Leander, and Bastrop. Those schools had been friendly enemies for decades, but now their whole seasons could be made by beating “the Cadillac Kids.” And they built solidarity in the cause. When we played basketball games in Leander, the bleachers swelled with Taylor and Georgetown fans. The post-game walks to the parking lot grew increasingly tense.

There were plenty of reasons those rivalries grew. We were sure they didn’t like us because they didn’t like to lose. Westlake was becoming a state powerhouse, and the first step each season was winning district. Typically we did.

The wins were accompanied by a cockiness we considered our right. We’d won our first state championship in a major sport, baseball, in 1980. The team was anchored by future major leaguers Kelly Gruber and Calvin Schiraldi, true world-class athletes who played with the swagger of kids who knew they were destined for pro sports. The other schools noticed, and when Gruber quarterbacked the football team, it wasn’t unusual to see our opponents bust through a sign that read, “Kill #5!”—Gruber’s number—when they ran onto the field.

And then there was money. When other schools visited us, they had to drive past our houses. The year I graduated, new Westlake homes sold for an average of $242,000, while in Austin the number was just under $100,000. (A longtime Taylor realtor I recently spoke with—who told me “I’m sorry for you” when I admitted where I was from—said he had still never sold a house for $250,000.) And when our rivals got to our parking lot, they had to drive past our cars. The guys we called the Trans Am Clan parked in a pack by the entrance, and jacked-up pickups and Jeeps had been bounced up curbs to a grassy area under some trees. Scattered throughout the rest of the lot was every sports car imaginable—Corvettes, Porsches, 280ZXs, BMWs, and the occasional Benz. It was as rarefied and stratified as the middle-school cafeteria had been. So when we played at other schools, of course we were greeted with signs reading, “We$tlake: Your Money’s No Good Here!”

There was no reason to be ashamed of (some of) our parents’ wealth, but there were other displays that should have been rethought. The homecoming football game during my senior year was played against Del Valle, an area where the primary industries were an Air Force base and a prison. The Cardinals were eight games into a 0-10 season; our ninth-ranked football team had yet to lose, and we beat Del Valle 37—0. But the worst insult came when the visitors had to watch our homecoming queen nominees parade around the track at halftime in Mercedes convertibles.

Three months later, when we played a basketball game in Del Valle’s gym, the Cardinals fans waved dollar bills at us from their side of the court. Those of us whose parents had entrusted us with credit cards responded by waving plastic back. Then we started a chant. “We’ve got Ronny, yes we do. We’ve got Ronny, how ’bout you?”—a reference to one of our star players, a high-scoring forward who’d transferred from Del Valle to play his junior and senior years with us. (Recruiting other school’s athletes was another accusation we frequently heard.) When the Del Valle side, whose racial makeup looked much more like the rest of the state’s, responded by chanting, “We’ve got niggers, yes we do . . .,” our fans actually shut up. Then we went on to win the game.

It was an especially tumultuous basketball campaign, new levels of bad blood having bubbled up during our undefeated regular season in football. Just before the playoffs, Leander, Georgetown, and Taylor had sued the University Interscholastic League, arguing that one of those schools should be going to the playoffs instead of us because the quarterback who led us to all those victories had been ineligible. The time it would have taken to try the suit would have meant the cancellation of the entire slate of 4A playoffs, and feeling the scornful eyes of the whole state upon us, Westlake agreed to a compromise: a qualifying playoff game against Taylor at the University of Texas’s Memorial Stadium.

The Austin American-Statesman called it the Injunction Bowl and ran stories every day for almost two weeks leading up to the game. When Friday night finally came, we sat on the visitors’ side, across the field from what looked like all of Taylor, Georgetown, and Leander. Some enterprising fans had flipped the appropriate seats in the empty upper deck to spell out “Taylor Ducks.” By the end of the first quarter, a Westlake kid had snuck up there and changed the D to an S.

On the field we were treated to what baseball fans call a pitchers’ duel. The source of all the controversy, our quarterback Todd Maroney, had broken the thumb on his throwing hand in practice that week, and without him we were incapable of moving the ball. The score was knotted 7—7 at halftime, and as our offense bogged down further in the second half, the Chaps fans grew frantic.

For most of the game, I sat far from the student section, with some buddies who’d already gone off to college, guys who now thought the whole high school thing was a joke. After Taylor went up 14—7 with six minutes to play, I moved down with the kids. There, things were different, with girls crying and guys cussing. We still trailed by 7 when, with 35 seconds left and the Chaps at midfield, our coach finally sent in Maroney.

I saw the Chaps faithful erupt, everyone babbling loudly about salvation and justice. With two quick plays, Maroney moved us inside the Ducks’ 30-yard line. Then he dropped back to pass and threw straight into the hands of a small Taylor defensive back.

The next few events seemed to unfold in slow motion. The Taylor player had a clear path down the near sideline. As he ran for the end zone, he started to taunt us. Then the biggest, meanest linebacker we had jumped from the bench and laid a shoulder into the kid, picking him up like a sock monkey in a pit bull’s mouth. We thought the kid might be dead. A free-for-all brawl broke out between the players. The Taylor stands emptied while we sat in shock. A Westlake player threw his helmet across the field at a circle of Taylor coaches. It could have killed someone. After order was restored, Taylor ran out the clock, and we drove back to Westlake as losers.

Our coach handled the situation as a gentleman should, promising his players that he’d resign if they ever broke down that way again. But the cement was already dry on what was now our statewide reputation.

A BUDDY WHO PLAYED in that game later won a football scholarship to Austin College, in Sherman, where he had a teammate who’d been an opponent in high school. They became friends, and the old opponent liked to joke that when he lined up against us, our offensive line smelled like Polo cologne.

I stayed in Austin for college, attending UT and making friends with some Taylor High exes. High school was over, and we got along great, though they did give me hell when Westlake made the papers for things like installing artificial turf on the football field, wrecking a hotel on prom night, and writing unforgivable racial slurs on the visitors’ bleachers at a homecoming game.

Westlake’s official response was to circle the wagons, and the common refrain thrown up in defense was one I’d heard often: “We’re in a fishbowl here, and everybody’s waiting to take a shot at us.” It was true. The papers didn’t give the same space to our football team’s wins or our National Merit Scholars. But it’s also true that the Chaps seldom bothered to look out of that fishbowl glass at the rest of the world, and that was a part of the problem.

My own reaction was a mix of embarrassment and regret. I’d been part of the problem as well. And though I never went so far as to say “Austin” instead of “Westlake” when people asked where I was from, I did occasionally catch myself wearing my dad’s old expression.