The romance of Anna Nicole Smith and J. Howard Marshall II served as the perfect summer replacement series for the O.J. Simpson courtroom drama and held its own against the tragicomedy that was the Lisa Marie Presley-Michael Jackson nuptials. In the minds of most Americans, Smith and Marshall quickly assumed familiar, straight-out-of-the-tabloid roles: She was, of course, the 26-year-old awesomely endowed “supermodel” who rose from a job as a breakfast cook as Jim’s Krispy Fried Chicken in dry, dust, dead-end Mexia to become a Playboy centerfold, Guess jeans girl, Playmate of the Year, fledgling movie star, and, finally, wife to one of the richest men in America. He was the 89-year-old wheelchair-bound “Houston oil baron” whose $500 million fortune landed him on the Forbes 400 list and who enjoyed treating his lady love to a supermarket-sweep-style shopping spree at Harry Winston. “God bless Anna Nicole; she found her sugar daddy,” declared professional wag George Wayne on a Geraldo dedicated to “Hot Gossip and Sizzling Celebrity Stories From the Summer of ’94.” The audience, which had just finished carping about Anna Nicole’s weight, IS, and attention span, gave him an ovation.

Since the story was something of an archetypal bombshell, it was natural that Houston, where both protagonists maintained homes, became ground zero in the fight for information. Pat Walker, the owner of the White Dove Wedding Chapel, where the wedding took place, received calls from reporters as far away as Germany and as early as four-thirty in the morning. (“I’ve told you everything I know,” Walker finally wailed to a relentless People reporter. “I don’t know anything else!”) Maître d’s and sommeliers at Anthony’s and the Confederate House—the tony Houston restaurants Marshall was known to frequent—were pumped incessantly for information; the once-invisible African American help at the River Oaks Country Club, where the couple secretly courted in a chandeliered dining room overlooking the golf course, experienced a dizzying rise in status somewhat comparable to that of the price of oil in the early eighties. Houston’s premier gossip columnists competed for scoops in typical fashion. The Post’s Betsy Parish was on the already panoramic dimensions of the tale by reminding readers of Marshall’s previous semi-secret relationship with—and ongoing multimillion-dollar lawsuit relating to—the late, great Lady Walker, arguably the fatale-ist femme in an extremely crowded local field. The Chronicle’s grande dame, Maxine Mesinger, deemed the whole story “overdone” even as she reported on Marshall sightings (at Anthony’s, with his nurse and driver) as well as his drinking habits (watered-down wine) and his apparent change of heart over some end-of-summer vacation plans (he didn’t go).

This tale had something for everyone: sex and money, grit, gumption, and greed, and love in its most complicated, convoluted, and confounding forms. But it was also, at its heart, a Houston story—in its gleeful tawdriness, its inspired profligacy, and its passion for self-creation. If you longed for the old Houston, if you wanted to prove the place had changed little in spite of booms, busts, and wave upon wave of tidy suburbanites, the love story of Anna Nicole Smith and J. Howard Marshall made the case.

Pat Walker, the good ol’ gal who runs the White Dove, had just scooted another wedding out the door of her converted pink ranch-style house when a black pickup careered down her pine-shaded drive in a blue-collar neighborhood off North Shepherd. It was Saturday, June 25. “We wanna book a weddin’,” the couple in the truck told her. They wore tired jeans and exhausted T-shirts, but right away they started ordering the best of everything—flowers, cake, you name it—and they wanted it in a hurry. “Money,” they told Walker, “is no object.” Reminding herself that you shouldn’t judge a book, Walker asked to see their marriage license, then gave the couple—relatives of the bride, it turned out—the bad news: Legally, no service could be performed until that piece of paper was 72 hours old. Monday the twenty-seventh at two-thirty would be the soonest any wedding could take place.

On the appointed day, at the appointed time, a very tall, very pretty bride arrived with her blond hair in curlers. A relative immediately began imploring Walker to please, please not call any reporters. “I’m not marrying him for his money,” the bride kept insisting, as if to herself, in a voice that was both frantic and girlish. “He’s been begging me to marry him for over four years. But I wanted to get my own career started first. Have my own money.”

Walker, whose interest in celebrities is refreshingly limited, listened to the young woman go on for a while, but finally she’d had enough. “Well, who are you?” she asked.

The bride stopped putting on her thick false eyelashes, her waist-length gown that had a train, puffed sleeves, a big bow at the back, and what Walker would later describe to People as a “very, very, very low-cut” neckline. “Well,” she said, blinking, “I’m Anna Nicole Smith.” Then she went back to putting on her clothes with the help of her bodyguard, Pierre, a large, handsome African American who wore a green tuxedo with a green shirt and lots of gold and diamonds. “He screamed Hollywood,” says Walker.

While the bride dressed, her little son and nephew, who were serving as ring bearers, killed time by tossing their satin pillows into the air—competing to see who could throw his higher. No one in the small party seemed to mind that Anna Nicole’s 22-carat diamond ring was tied to one of the pillows—not the groom, a tiny but deliriously happy man in a wheelchair who wore a white tux, a white shirt, and white shoes; not his nurse; not his secretary; not even Pierre. Walker thought it strange, particularly since the bride had written in the bride’s book provided by the chapel, “This is the third ring I’ve had—the others were too small.”

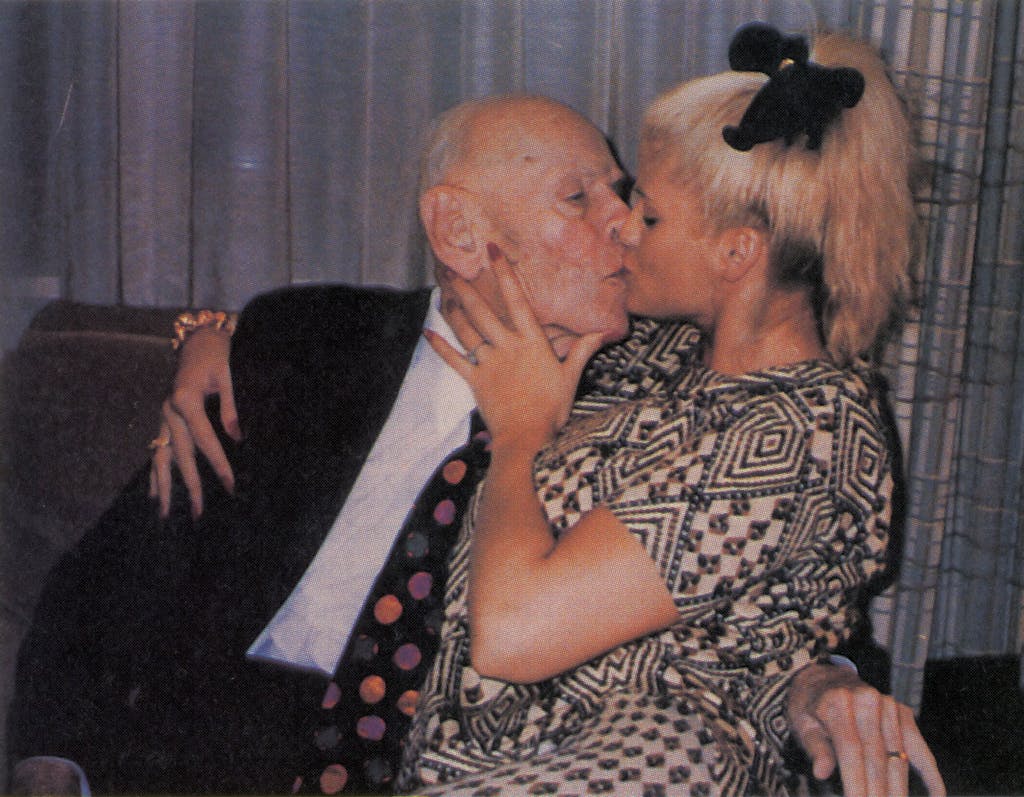

Anna Nicole was far more romantic about the couple’s first meeting. “I was on stage,” she wrote under the “How We Met” heading in the bride’s book. “He was in the audience, and he was lonely and I started talking to him and we just started being friends.” And she insisted on a traditional white wedding. “White, white, white,” Walker recalls. “They couldn’t stress that enough.” She had draped the small, sunny chapel with white ribbons (the walls and folding chairs, thank goodness, were already white) and had carpeted the mauve aisle with white flowers. “She walked on white roses,” Walker says of the bride. “Not petals. Buds.” When Anna Nicole Smith stepped down the aisle, she looked to Walker “like a goddess,” albeit one who might have had a stopover in Vegas.

The ceremony included a taped version of “Tonight I Celebrate My Love for You.” The vows were recited, and then the groom, one of the richest men in America, was wheeled up the aisle behind his bride, one of the most famous women in America. Walking out of the chapel into the sunlight, Anna Nicole turned to a cage containing two white doves. It was the specialty that gave the White Dove its name. Together, the bride and groom let the birds go, watching them fly to the freedom that lay just beyond the pines. After a brief reception in a small room adjacent to the chapel, Anna Nicole would do the same: In a disguise consisting of a wig, floppy hat, sandals, and a tight yellow suit, she made for the exit, saying she had a photo shoot in Greece. The groom wept. “Please don’t cwy,” she cooed to Marshall. “Yew know it’s yew ah luv!” Then, with her bodyguard, she was gone.

At that moment, Pat Walker stopped wondering and started understanding. “I think she’s real smart,” Walker says, analyzing her first and only encounter with Anna Nicole Smith. “And I tell that to everybody.”

The rare few who examine Anna Nicole Smith’s 1993 Playmate of the Year video for its biographical rather than erotic content will find the film instructive, and not because the star describes her former home of Mexia as “a small town just outside of Houston.” There, between interludes of Anna Nicole portraying a gambler’s bored babe or Anna Nicole scrubbing clothes on a washboard while wearing a faded housedress over an expensive black bra, is the star-to-be’s official biography. It is the story that she has carefully shaped and endlessly repeated to journalist after journalist, and the then-25-year-old narrates the film like a joyous teenager, tossing her blond hair and dipping her astounding chest, her soft voice carrying the hint of a giggle, her smile rapturous. We see the treeless plains south of Dallas, the appropriately folksy townspeople, the fabled chicken shack where she met her first husband, Billy Smith, at age sixteen. She reminds us that at eighteen she already “had married, become a mother, and gotten divorced. “This is the house I grew up in,” Anna Nicole says, beaming as she gestures like a game-show hostess toward the tiny frame house where she once wore flannel pajamas under her clothes to keep warm in winter, where her aunt Kay Beall slipped her food stamps to buy candy.

There is scant mention in the video that young Anna Nicole was shuttled between the homes of her mother and her aunt—and no mention that she began life as Vickie Lynn Hogan—but much is made of a gently orchestrated reunion between Anna Nicole and the father who abandoned her as a child. “He’s my daayaady,” she says, cozying up to the abashed man as she smiles kittenishly at the camera. You can’t help thinking how nicely she fits the Playboy mold: She appears to be a girl who is very pretty, not very smart, and who had worked very hard for everything she’s got. “The thing that makes me happiest is being able to do things for my friends and family, especially my son, Daniel,” she says sweetly. Sitting astride a horse in a pasture, she waves her arms beyond grazing cattle toward a hulking brick mansion in the distance. “And this is my ranch I’ve wanted all my life.” No one need know that the ranch was then and is now owned by J. Howard Marshall; that would change the story, complicate the picture. And Anna Nicole Smith seems to know absolutely that American men want their sex symbols as pure and simple as the Texas prairie.

Indeed, her fans seemed more than willing to accept the fable Anna Nicole fashioned for herself the one that cast her as the prototypical innocent, the Wal-Mart cashier, the Red Lobster waitress, the woman whose merely average breasts grew to a DD cup in a miraculous blossoming after her pregnancy. She liked to tell reporters that she had quaked before the lens of the centerfold photographer. “I never used to even let my boyfriend have the lights on when we were in bed,” she told a writer for People. “I didn’t want him to see my body or anything.”

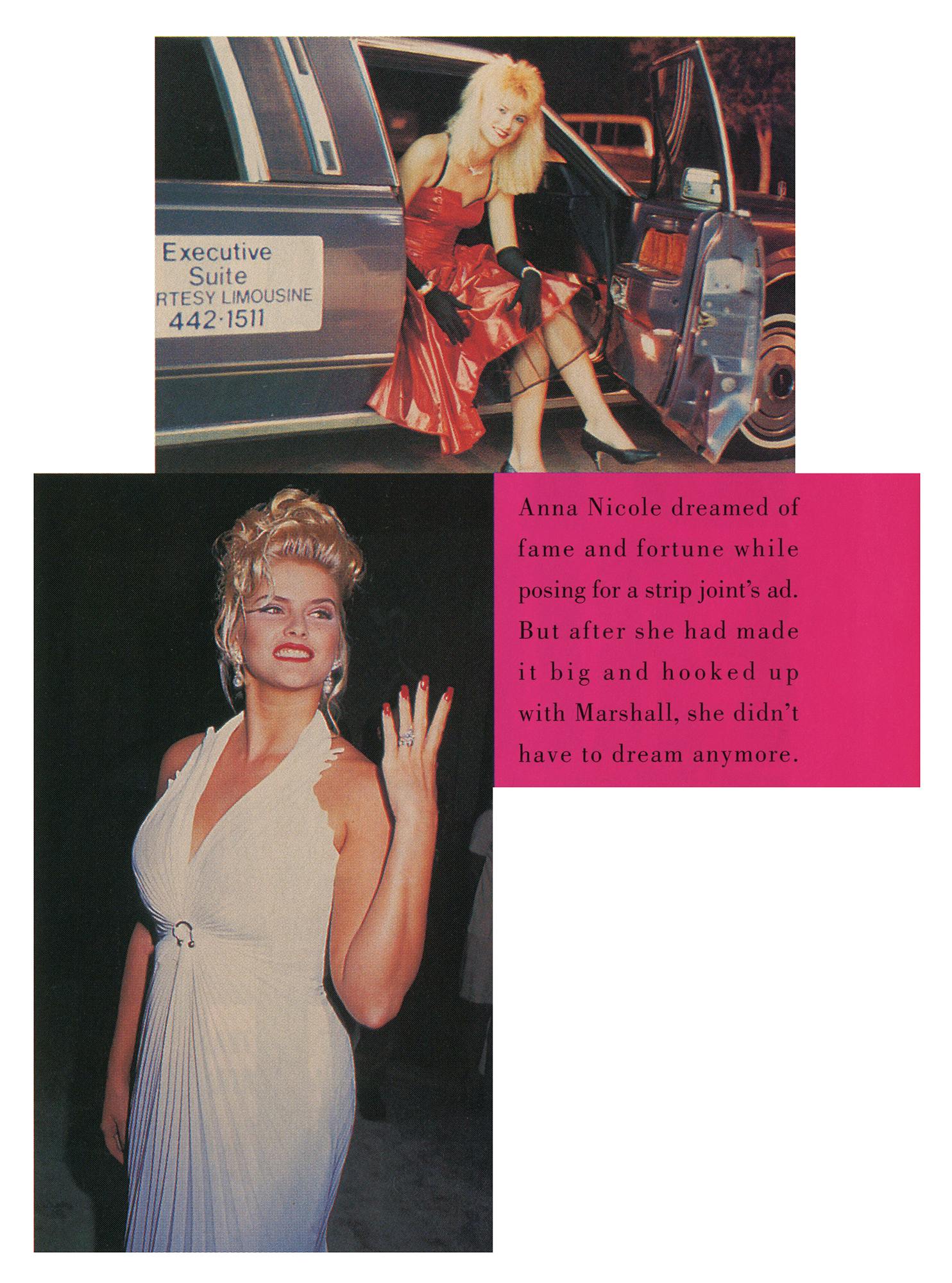

The truth is a somewhat seamier but far more credible story that reveals an asset Anna Nicole Smith is not widely known for: shrewdness. She had been a pretty but wild sort of girl in Mexia—“All the guys wanted to go out with her, all the girls were jealous of her,” remembers childhood friend Jo Lynn Aguirre. She was also headstrong and hungry; the young girl who had grown up with every kind of deprivation—physical, emotional, financial—had big but unrefined dreams. “She wanted to be a model, but she didn’t know how to do it,” Jo Lynn says. After dropping out of high school and moving to Houston with her six-month-old baby in 1986, Vickie Smith must have seen quickly that waiting tables at the Red Lobster in Humble was not going to cover her bills.

And so, in 1987, she took the path of so many pretty girls with no education but plenty of drive. She wandered into a men’s club called the Executive Suite, looking for a job as a dancer. The Executive Suite was then the most upscale topless club on the north side, one of those dimly lit, semi-plush places that create the aura of catering to businessmen, offering a limo to and from Houston Intercontinental Airport and various nearby hotels. The manager, a taciturn man with sleepy blue eyes named Terry Allen, sized up nineteen-year-old Vickie Smith and offered her a job. “I could tell she had a lot of potential—she was a pretty girl,” he says. A photographer who did some work for the club at the time recalls cruising the place for girls to photograph for the brochure. In the corner he spied a shy, delicate blond with a heart-shaped face. He asked her if she wanted her picture taken and, he remembers, “She went to stand up and then this immense girl was standing in front of me.” Vickie Smith was a full five feet eleven inches tall. “She definitely stood out among the girls,” he says. “She didn’t have the hard look.”

A year or so later, the photographer bumped into her again. “It’s like someone took her into a laboratory and recreated her,” he says of the woman who was then dancing under the names Nikki and Robin. “She was more sophisticated. Aloof. She was into the program; she was there for dollars and cents.” Onstage, she danced with particular zest to Prince’s “Darling Nikki,” but she learned quickly to save her best work for her well-paying regulars, tucking them into a corner and whispering baby talk while she writhed and wriggled for them alone. “She knew the business and she pushed it to the limit,” the photographer says.

Vickie Smith was at home in the men’s club subculture, with its late nights, big money, hard partying, and anything-goes sexuality. She was making $50 to $200 a day and, like so many girls who had come from nothing, she had trouble holding onto her cash. She enlisted club manager Allen’s help in saving for a breast augmentation—“That’s what she was lacking,” he says; “she needed tits in proportion to her body”—but she was forever taking back the money she’d asked him to put aside. Even so, she eventually found a way to improve her figure; Allen, among others, recalls at least two operations. On one visit to Mexia, she wowed her friend Jo Lynn. “She was absolutely gorgeous,” Jo Lynn says. “She had colored her hair champagne blond. Her body was perfect. She had filled out.”

As the eighties ended, Vickie made the rounds of other north side clubs, places with pseudo-glamorous names like Chez Paris, Puzzles, and Gigi’s. Her good-girl looks made her a natural for club ads—she posed in fake furs and rhinestones or lounging across a Porsche. But real upward mobility was tougher. Vickie tried her hand at the more stylish clubs in singles-dominated southwest Houston—Baby O’s and the Colorado Club—but those places liked their dancers thin. “We considered disciplining her for her plumpness,” says Robert Waters, the owner of Rick’s, Houston’s best-known men’s club. At Rick’s, she was judged good enough for the day shift but not for the nights, which paid better. That rejection may have been the luckiest break of her life, because one day in 1988, a frail, ancient man was sitting in the lunchtime audience. As she would later write in her bride’s book, she was onstage and he was lonely, and they started talking and became very good friends.

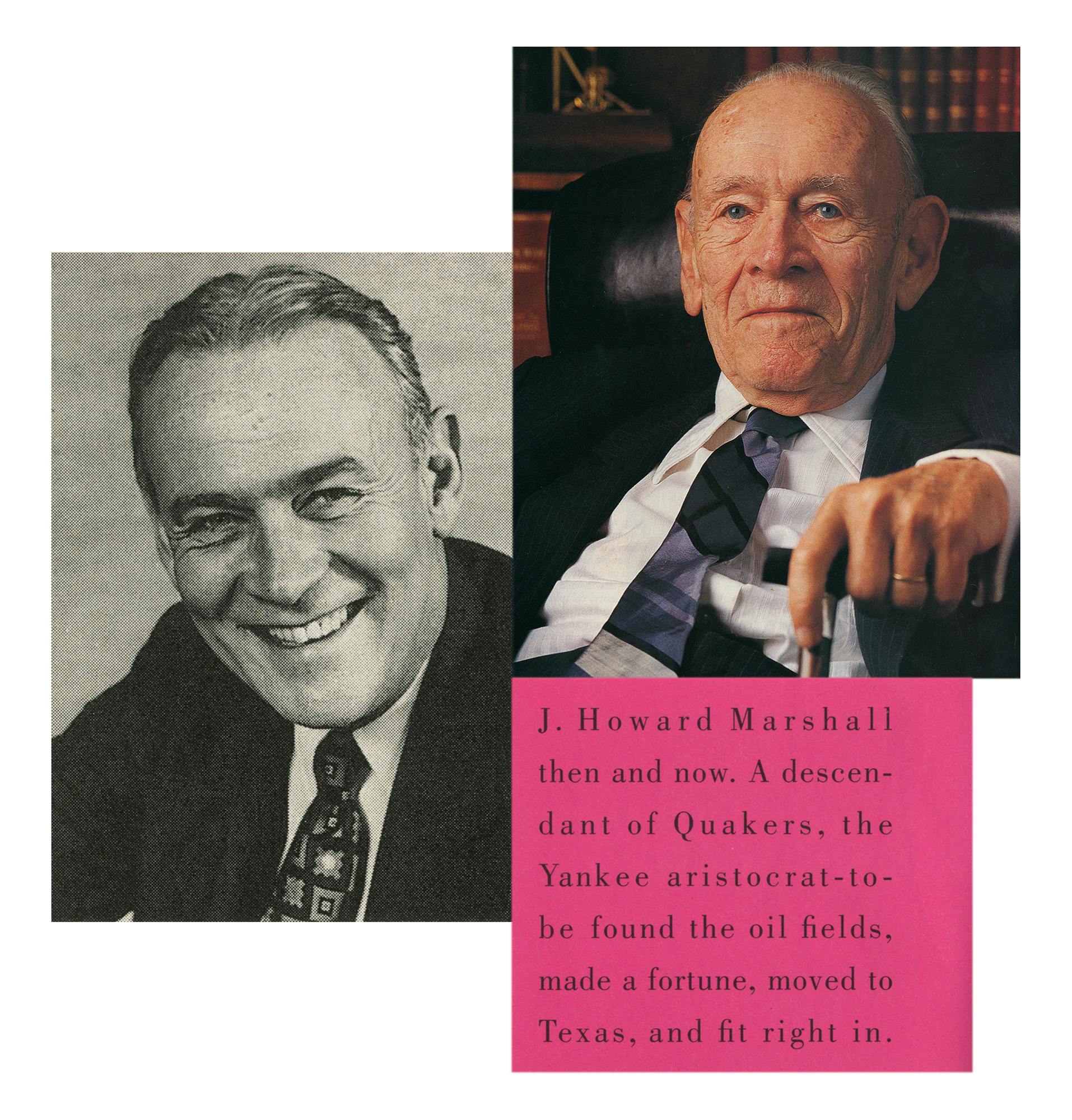

The word “oilman” calls to mind a Jett Rink type, someone coarse, unwashed, and uneducated who gets his way no matter what. By no stretch of the imagination does J. Howard Marshall II fit that bill. In fact, he began life closer to the reverse stereotype, the Yankee aristocrat. A distant relative of Supreme Court chief justice John Marshall, he was born in Pennsylvania in 1905, the son of Quakers, and addressed his elders as “thee” and “thou.” His grandfather had made a fortune in steel, selling out to Andrew Carnegie for around $18 million in 1902, but the family fortune dwindled during the Depression. Young Howard put himself through Haverford, a Quaker school known for academic excellence, and went on to the Yale School of Law, where he rose to the top of his class.

A childhood illness may have been the factor that most shaped Marshall’s psyche and directed him away from the staid life of a Yankee blue blood. He contracted typhoid fever when he was twelve. As he explains in his autobiography, Done in Oil, to be published in December by Texas A&M University Press, “The inflammation had virtually destroyed my left hip joint and about five inches of the bone from the ball and the socket. The doctors said I would never walk again. My mother, a very strong person, disagreed, and, after I’d been on crutches many months she took them away, burned them, and told me to walk. I staggered, stumbled, and fell—but the more I used my hip, the less it hurt.”

Though he would always walk with a limp, Marshall grew up supremely confident, essentially fearless, as fierce at soccer and tennis as he was in debate. He would evolve into a tiny, not unhandsome man with huge ears, a man with a booming voice when angry and with the wicked wit that short men sometimes develop. He was influential and rich enough, and he loved beautiful women and practical jokes. As a young man in Philadelphia, he resented a young deb’s snub so much that he spoiled her debut by printing up 1,500 extra invitations and handing them out on the street. In other words, fate made Howard Marshall wild enough and tough enough for the oil patch.

He landed there, in the Oklahoma fields, in 1931 while researching an article for the Yale Law Journal. It was the beginning of the great East Texas boom. Two years later, while assistant dean of the law school, the 28-year-old Marshall was asked by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to investigate the “hot oil” wars between Texas Railroad Commission regulators and the oil producers who exceeded the legal maximums. In his work Marshall stormed refineries, dodged bullets, and made the kinds of contacts, including the vastly rich geologist Everette DeGolyer, that facilitate later fortunes. He also found his life’s work, which was, essentially, devising ways to regulate what he called the “high-risk, speculative, rough and tumble” oil business without stifling it. Like many classic oilmen, he would become an expert at turning rules to his advantage.

And his country’s. During World War II, after a stint with Standard Oil in California, Marshall served as chief counsel to the Petroleum Administration for War, which ran the domestic oil industry. In 1944 he moved on to executive positions, helping Ashland Oil emerge from independent status to become a major company and, later, greatly expanding the properties and profits of Signal Oil and Gas. At Signal in California, in the fifties, he learned to take an ownership stake rather than a salary increase for his expertise in dealmaking, significantly adding to his wealth.

He was lured to Houston in 1961 to work on the various mergers that would create Allied Chemical. Local oilman Jay Grubb recalls that working with Marshall then was “a pretty fast run, very stimulating, tremendous fin. He’s a guy who worked very hard, made lots of deals, and figured if you made a lot of ’em, you’d make more good deals than bad.” Btu Marshall did not accumulate enormous wealth until he made a deal with Fred Koch in the early sixties. Koch, an old friend from his Washington days, had invented a highly efficient gasoline-refining process and owned what would become Koch Industries, the largest privately held energy firm in the country. The two men had invested in the Great Northern Oil Company’s Minnesota refinery in the fifties, and Marshall eventually folded his interest in it into Koch’s conglomerate, making himself a millionaire hundreds of times over. As he says in his autobiography, “It turned out to be the best deal I ever made.”

But the deal was not without its price. During the early eighties, when several of Koch’s brothers wanted to increase the company’s growth by taking it public, Marshall, who then controlled 8 percent of the stock, sided with family members who wanted to keep Koch Industries out of the hands of outsiders. His elder son and namesake, J. Howard Marshall III, who owned the stock with him, sided against his father. In order to keep the company private, the senior Marshall bought out his son for $8 million and began an estrangement that continues to this day. Howard Marshall was not one to let sentiment get in his way. Or so it appeared.

By the end of 1982, Marshall was 77 and in the position of many rich, successful men: He was an esteemed member of his particular community, a master of every aspect of the oil business “from exploration to marketing, from the courtroom to the government,” he writes, “and from the major corporations to the independents.” He had his own company, Marshall Petroleum, and continued to be involved in new ventures. But he had no one to enjoy his success with. His first marriage, to Eleanor Pierce, a college sweetheart who, he writes, “never really understood my driving passion for the oil business,” lasted thirty years but ended in divorce in 1961, the year he moved to Houston. His relations with his younger son, Pierce, were testy at best. He had envisioned a happy future with his second wife, Bettye Bohanon, whom he had married in 1961. Tiger, as he called her, had been a true partner who had shared his love of the oil business—she had worked alongside him throughout most of his first marriage—but now she was ill with Alzheimer’s. He was alone.

Then, as Marshall would explain in connection with a lawsuit filed in 1992, love came back into his life after what you might call a hard day in the oil patch. “I landed at the Houston Hobby Airport and driving home, I thought, well, maybe if I had a drink I’d feel better, so I stopped at some little place that I didn’t realize what I was getting into. It was a strip joint—or as the boys call it now—a titty bar. And I walked in and Lady was there. She was one of the strippers.”

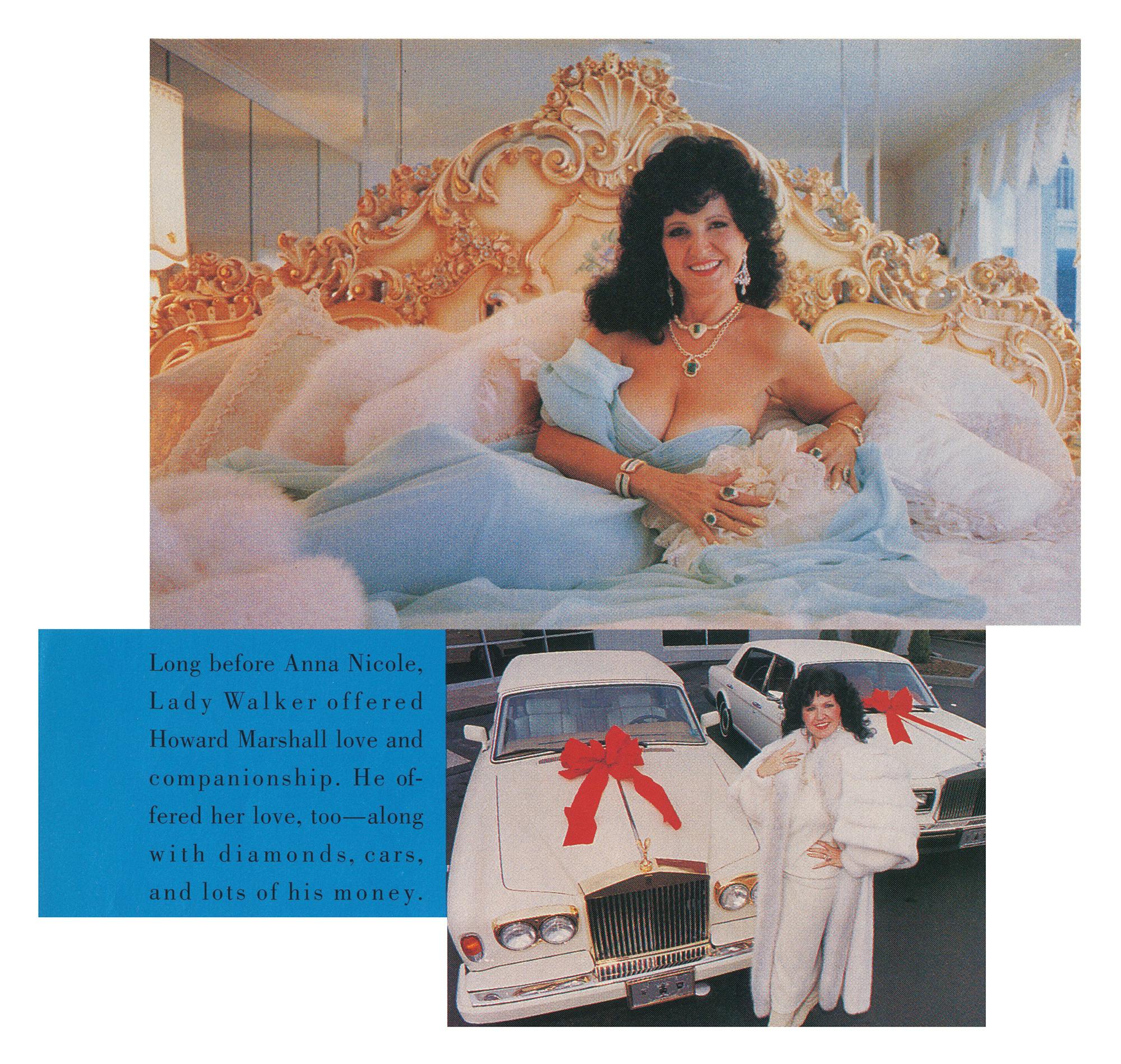

Her real name was Dianne Walker—Jewel Dianne Walker—though most of her friends called her by her childhood nickname, Lady. She, too, was going through a particularly hard time. A native of Valdosta, Georgia, she had been in Houston for two years. In 1982 she was facing her fourth divorce—her husband had gone back home to Georgia, leaving her with two daughters and one son to support. She had worked as a secretary, a receptionist, a restaurant hostess, and a product demonstrator, and she wasn’t making anywhere near enough money. So she took the path of so many pretty women with no education but plenty of drive: She became a topless dancer at a place called the Chic Lounge, located on Hillcroft, just off the Southwest Freeway, near what was then the center of the city’s singles scene. She was 42, but you’d never have known it.

It is frequently said that photographs do not capture the beauty of Lady Walker. She had a Southern woman’s flawless complexion and delicate charm, that ability to make everyone, men in particular, want to be in her company. (She liked to tell people that she had had on-again, off-again affairs with Elvis Presley and Pete Rose.) She had a child’s sense of wonder, and when she spoke, her voice was cultured and soft as a caress. “More Georgia peach than Georgia cracker,” explains a fan. She was tall and more than amply endowed, with a tiny waist and legs that went on forever. Since Lady is remembered almost universally for having lived up to her name it is hard to imagine what, exactly, she did at the Chic Lounge that so completely seduced J. Howard Marshall II. But she clearly gave the performance of her career.

According to deposition testimony later given by both Marshall and Lady’s eldest daughter, Cerece Walker, Marshall paid for a private dance that night and returned at least twice. Within a few weeks he had bought Lady a Cadillac El Dorado. “She needed a car,” Cerece explained. And a new house, a model home they bought furnished. And a diamond ring. Howard Marshall, hard-bitten oilman, had fallen utterly, helplessly, totally into the realm of cliché. As he would later testify, “I was blinded by love. I did more or less what she asked me to do, and I don’t make any bones about it. I was a damn fool. But men in love do stupid things, and I was sure guilty.” How fully Lady Walker came to return Howard Marshall’s love is the subtext of a lawsuit set for trial this October; that she soaked him financially, with an enthusiasm and artistry bordering on brilliance, is indisputable.

Very soon after that fortuitous first meeting at the strip joint, Marshall did what he always did when he saw something he wanted. He cut a deal: his largesse for Lady’s company. His wife was seriously ill; to Marshall this meant that he could not be seen with another woman in the evening. Lunch, however, was a different matter. Howard and Lady soon established a pattern from which they barely deviated for almost ten years. Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday he showed her off at Houston’s finest and flashiest restaurants, crossing the scarlet floral carpet at Tony’s, dining behind the ferns and white latticework at the Rivoli, or sipping coffee under the kind, rosy light at Maxim’s. And while Marshall resembled any number of successful elderly businessmen, Lady was, before long, unmistakable. By the end of 1983, he had given her close to half a million dollars, and she had used it to turn herself into the Lady of her fantasies. Conversation would stop whenever she entered the room in one of her ensembles—the enormous hats that matched the gloves that matched the scarves that matched the shoes—and the diamond that, of course, matched just about everything. “Lady would walk in with her bodyguard, all in white—white fur, white dress,” Betsy Parish recalls. “You could not help but stare at her. She could not quietly have lunch with anyone.”

Lunch would last about an hour and a half. Sometimes the couple dined alone, but more often with a jeweler bearing a new gift for Lady—created by Lady and paid for by Howard—or with Lady’s closest friend and business manager, a women whom both Lady and Howard had chosen for the job. On rare occasions, there were celebrities in attendance, a Roosevelt descendant, perhaps, or John Connally or the über-oilman himself, Oscar Wyatt. Usually, Marshall talked—geopolitics or oil prices, or his recollections of the Yalta conference, Hitler’s bunker, or of sharing a dirty joke with Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas—while his guests listened in awe. During the meal he would pass Lady a handful of blank checks under the table. The one time he passed her a few in plain sight, she was miffed. “Put it in my purse,” she scolded him. “Don’t just hand it across the table.”

He could barely stand to be away from her, and he constructed a fantasy of himself as her protector, the one person who stood between Lady and a poverty she had never experienced but that seemed, always, perilously imminent. “I hope you never need sell it to eat,” Marshall wrote in a note he enclosed with a gift of a gold coin that had come from Saudi Arabia. The American government had briefly minted the coins to pay King Saud for his oil, Marshall told Lady; the king had in turn passed them on to his mistresses. Marshall suggested that his own mistress checked the coin for teeth marks.

There were private jokes about “pin money” versus “jungle money” (spare change versus real deal money) and short mash notes scribbled on the back of travel itineraries, or, once, on the back of an invitation to a dinner the Mosbachers gave for the Bushes. The letters of those years run together to form a river of passion, its source a man whose passion, in earlier times, seems to have been directed elsewhere. “To love and be loved—to a man who has dedicated his life to his work, this is truly life greatest experience,” he wrote in one letter. In another: “In the years to come I hope we will sleep together in the same room, the same bed and wake up in the morning together. And whether your hair is combed and your face without makeup will not diminish my love for the whole lady by so much as a micromillimeter!” And still another: “Yesterday you seemed so distressed, discouraged and lonely. Remember my sweet you are never alone…Let my love hold you tight, lean on me, believe in me, I belong to you.”

A simple arrangement had become a psychological imperative. He would support Lady until his wife died, and then, according to his fantasy, they would marry—at dusk in the Taj Mahal. As he explained in a letter to Lady’s mother, “I would marry her this afternoon…if I were free to and she would have me. I cannot leave an ill wife to whom I have been married. I think it might kill her and I would feel guilty for the rest of my life. Perhaps a time will come. But it cannot be forced.” Sex seems to have been a less than essential part of the bargain: “If a little pat means a Paris hat,” they’d joke in almost Victorian fashion, “who am I to say nay?” In deposition testimony, Marshall cited at least three sexual encounters—one at the Houstonian resort, one in his office, and one in his home—but admitted he and Lady had ended their physical relationship by mutual consent when he was 83. Those close to Lady doubt that there was ever any sex at all. After all, she had a vested interest in appearing to be a lady—pure, delicate, in need of protection.

Lady’s private view of this arrangement is difficult to discern. What remains of her correspondence to Howard is mostly notes written in her florid script on the bottom of sentimental birthday cards. (“Dearest, I shipped the briefcase to Cerece from us knowing that you have a wonderful real elephant briefcase but I had to let you know I was thinking of you.”) She is remembered as a kind person—she had a sunny wave for everyone, from society scribes to floor buffers at Saks—and her children and close friends say she was indeed in love with Marshall and planned to marry him. He may have been old, but he was entertaining and he knew how the world worked, and he was more than willing to share his knowledge and his contacts with her. Above all, he worshiped her. Even so, in her early forties, Lady was a comparatively young woman, and she made it clear that she intended to get on with her life as long as Marshall remained married. As Cerece Walker would later claim, “I think they were both getting what they wanted out of the relationship, and I think that when they were together that was what mattered, and then when they were apart, they had other things going on.”

Mostly, Lady shopped. Marshall may have been a multimillionaire, but in 1984 alone she went through $1.2 million of his fortune. “I think a lot of people feel another person inside, but they’re afraid to show it,” she told a Post fashion reporter in 1990. “I don’t mind showing that side. When other women were wearing little ear bobs, I searched forever for a pair of gold hoops. I’ve always been flashy wherever I could flash.” Marshall’s money allowed her to indulge her fantasies in ways that few people could even imagine. A jeweler friend of Cerece’s was basically put on retainer. Marshall made it clear that he did not want to be bothered with any details; Lady was simply to have anything she wanted. Very soon, he began paying $25,000 a month on an account that quickly soared into six figures. She bought, among many other things, a pair of emerald-and-diamond earrings for $50,000. Platinum-and-diamond earrings for $130,000. A $128,000 diamond that was delivered to her in Valdosta. Enough never seemed to be enough. Lady even had the jeweler create fourteen-karat-gold false fingernails, at $5 apiece.

To go with her jewels, Lady picked up Bob Mackie couture gowns at Saks, shopped at Liberace’s furrier in Vegas (she spruced up one fox pelt by adding rhinestone eyes), bought Rolls-Royces and Jaguars that matched her clothes. Marshall bought her a mini-manse overlooking a golf course in Sugar Creek, where she had virtually everything inside and out painted white or gold. Her name was spelled out in tiles on the bottom of the swimming pool, which had been designed by the same artist who did Liberace’s. The man who paid for all this was never allowed to visit. “When I can set foot in his house as Mrs. Marshall, he can set foot in mine,” she liked to say.

It wasn’t just Lady that Marshall supported. “Your family is my family,” he wrote her, and she took him at his word. He helped pay her son’s tuition at Southern Methodist University, and though Lady’s parents sometimes shared her home, he bought property for them in Georgia. Cerece’s wedding in 1987 became, for Lady, a personal triumph. She had always believed that her own early marriage—the proverbial cheerleader-football star union—had been destroyed by in-laws who had seen her as socially inferior; now she could return to Valdosta victorious and rub the whole town’s nose in her wealth. “It was the biggest bash the town had ever seen,” recalls a guest. “She went home in a Rolls-Royce.”

Houston was more forgiving. Few society reporters could resist her flamboyance; except for a handful of River Oaks matrons, no one really cared where her money had come from. But she was still a mistress: Outside of her family, a few close friends, and a growing list of tradespeople, she was alone. And Lady hated to be alone. So on nights she was away from Howard, and there were many, she took to hitting singles bars. He may not have needed sex, but she did.

Lady had a lover named Dale Habada when Marshall came on the scene. But by 1987, she had become more refined under Marshall’s tutelage, and she sent Habada packing. “He liked going to strip clubs…She had gotten more social,” Cerece explained. In 1988, however, Lady found another Dale she could not resist. He was Dale Clem, a hunky thirtyish carpenter-shrimper she had met at a fifties-music dance club called Studebaker’s and had hired, with Howard’s approval, as her bodyguard. Testifying in his deposition, Clem recalled Lady’s attire at his job interview. “She was dressed to go out. She was in a pair of leather turquoise pants, a gold top, big earrings, jewelry, ready to go paint the town, I reckon,” he said. “It’s not every day you run into somebody like Lady was, how she acted and carried on. If you’re from a little town of Baytown—it sort of burns your brain a little bit with it.”

She spun her own fantasy for Clem, telling him her money had come from a divorce settlement: The father of the Santa Fe Railroad heir she had married had decided she “deserved something.” Marshall, she explained, was a business manager, a friend. When she and Clem became lovers, Lady turned the younger man into a kind of mirror image of herself. She asked him to give up other jobs to devote himself exclusively to her, and he obliged; there were trips to Las Vegas, fur coats (“Dadgum, what is the name of that place?” he testified, trying to recall a store. “It’s on Post Oak…”), and, of course, diamonds. A Mercedes-emblem ring. A Cadillac-emblem ring. Whenever Clem’s back pocket was empty of cash, she replenished it. How much Howard Marshall knew about the two Dales—“live-ins,” as he would later call them—is now at the center of a multimillion-dollar lawsuit. But at the time, he did not make an issue of it. His lunches with Lady continued unabated. She was a willing student, as hungry to learn about oil deals as Paris fashions. As her enthusiasm grew, Marshall signed over more and more of his holdings to her. Sometimes he gave her pieces of his wife’s jewelry; sometimes he offered stocks, bonds, or real estate. He made her the beneficiary of his life insurance policy; he created an oil company, Colesseum, for her. It was as if he could not funnel her money fast enough. “Dear Pierce,” he wrote in a letter he did not show his son until 1991, revealing to him Lady’s existence in a spidery scrawl, “If I predecease you as a father who loves you, I charge you to take care of her in any way she may need, financially and in all ways…I am completely obligated to take care of her!”

But by 1991, Lady had grown moody; she fought uncharacteristically with her family and close friends, and sought psychiatric help. There had been fights with Howard over gift taxes—when Pierce Marshall discovered that his father had never reported the millions he had given Lady in their nine-year relationship, Pierce insisted that he comply with the law, which requires reporting gifts of more than $10,000 a year. Lady was left liable for millions in unpaid taxes. “I found it more than a little shocking that her minimum standard of living required one hundred thousand dollars a month,” Pierce later testified in a deposition. Without telling Lady, Howard briefly closed a checking account he had established for her, causing her to bounce checks all over town. They argued. Sometimes she would retreat to the first house Marshall had bought her back in the old, less complicated days and sit for hours, just listening to the rain on the patio’s tin roof. Maybe she was losing faith that she would ever be the oilman’s wife. Or maybe, as Dale Clem figured, she was just afraid of growing old. It could have been that simple: Lady scheduled a face life for the beginning of July.

For some reason, she rewrote her will the night before the operation, on the back of some pink message slips she put in a vase in her daughter’s room. She left the bulk of her estate to her children. “My personal jewelry divided between my girls Cerece and Starr and the furs likewise,” she wrote, “which are in James Furlan furriers [along with a] sable coat…and a [full-length] black mink coat and full-length white mink coat at Roy La Noble Furrier at Dunes hotel, Las Vegas.” To Dale Clem she left a truck, $30,000, a bracelet with his name in diamonds, and Fancy, their poodle. “I leave all my love to you and will meet you sooner than you know,” she concluded. At 51, she died on the operating table of a congenital brain defect, according to autopsy reports. In the Post obituary she was described as a “socialite.”

Marshall paid for the $52,000 funeral, which included a copper coffin—similar to Elvis’—that was so heavy it had to be driven rather than flown to Georgia. The hearse was trailed by an empty limousine bearing a single red rose. “Lady Dianne Walker,” Marshall wrote in a note he sent to the funeral on July 11, “We both loved poetry and song. Wherever you are I hope you can hear me say once again, ‘I could not love thee half so much, loved I not honor more.’ Better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. I never loved thee casually. Till we meet again in the next world, you own man, now and forever, Howard.”

The next few months were difficult for Marshall. In late July, he checked into the country’s most exclusive men’s retreat, the Bohemian Grove, north of San Francisco, for a few days’ rest. He returned home only to receive another shock when he learned the contents of Lady’s will. That led to a very unpleasant lunch with Dale Clem at the River Oaks Country Club. Amid the delicate clinking of silverware and the obliviousness of venerable bank presidents and corporate lawyers, Clem spelled out for Marshall his sex life with Lady. Adding to his pain, Bettye Marshall died in September.

He was grief-stricken, but somehow able to act. In February 1992, Marshall, helped by his son Pierce, sued the heirs of Lady Walker—and some of her friends too. He wanted back every penny he had ever given her.

Courthouse records show Marshall to be a man who believes in solving his problems in court. As one attorney inquired in a deposition, citing a previous case in which Marshall had showered gifts on and subsequently sued an employee, “Can you identify a single person who has worked for Mr. Marshall in a personal capacity…who has not been accused of some infidelity by Mr. Marshall?” In this suit, Marshall claimed that Lady had given the appearance of loving him exclusively while carrying on affairs with other men. He further asserted that the gifts he had given her had been given in trust; Lady wasn’t to own them until his death. With the help of friends and family, she had “swindled” him out of his fortune via a series of frauds and kickbacks,

It was the suit of a bitter man. There is little evidence that Marshall’s gifts to Lady came with any strings attached, and his insistence that she was obliged to remain true to him while he was married smacks of revisionism. Besides, if deposition testimony is to be believed, Marshall would have to have known of the existence of Lady’s lovers. They answered the phone at her home; she told Marshall, in front of witnesses, that as long as he was married she would continue to see other men, and he complained about that fact to at least one of Lady’s close friends. It may be that, until his lunch with Dale Clem, Marshall had turned a blind eye to the extent of Lady’s sexual needs. It may be, too, that his reasons for suing were more pragmatic: He needed to retrieve some $1 million in stock he had transferred to Lady in violation of Securities and Exchange Commission rules, and he could clear up some potential IRS problems arising from unreported gifts. And besides, he had a new deal working. If Anna Nicole’s public pronouncements are true, Marshall was asking her to marry him as early as 1990.

As Anna Nicole Smith has often told reporters, she did concentrate on her career far more than on J. Howard Marshall for at least a few years. Until 1991, he was ostensibly busy with Lady Walker, and she, as Vickie Smith, was making a go of it as a dancer. She thought of Marshall as Lady had initially—as a friend. Sometimes she talked baby talk to him on the phone late in the evening, and one Christmas she gave him two poster-size color portraits of herself wearing a G-string and a lacy transparent top. Sometimes, particularly when she was low on money, she met him for lunch at the River Oaks Country Club. These meetings probably became less frequent after a test shot landed her on the March 1992 cover of Playboy, portraying a demure debutante. (She neglected to tell the screening photographer that she was employed as a dancer—Playboy likes its girls fresh.) By the time she was chosen Miss May of that year, Vickie Smith was busy doing things all Playmates do. She was starring in erotic Playboy videos, pressing her pneumatic breasts into wet sand near a pounding surf, draping herself in black gauze while blindfolded boy toys stood sentrylike behind her. She went on promotional tours, where signing autographs could be a challenge (she spelled “Fred” F-r-e-a-d). And though she would develop the requisite Marilyn Monroe obsession, Vickie Smith was not one to put on airs—she fought with her manager when he thought her clothes were too tight (“I got into it, didn’t I?”) and never minded at all if, when she was out dancing for fun, her breasts popped out of her top.

It was Guess president Paul Marciano who transformed Vickie Smith into Anna Nicole Smith. As has frequently been told, he saw her pictures in Playboy, flew her to a test shot in San Antonio, renamed her, and turned her into a sex symbol. The Guess shots are indisputably the most beautiful photographs ever taken of Anna Nicole, perhaps because Marciano did not lock her into the girl-next-door mold. Fingering the shoulder strap of a clingy black dress or facing the camera squarely in a plunging shirtwaist, she looks like who she is—a rough-edged but not unsavvy blonde who likes sex almost as much as she likes having her picture taken. “She is one of the most awesome people in front of the camera I’ve ever seen,” says a well-known photographer. “She gets into a sexual trance. You could turn the camera on and leave the room and she’d keep on going.”

So, by Christmas 1992, Anna Nicole Smith wasn’t doing badly at all. To celebrate, she invited her family over to her ranch house for a dinner of potato chips with pimento cheese and tuna sandwiches with the crusts cut off. Howard Marshall was present in spirit only. He had paid for the house.

Anna Nicole had never really let Paw-Paw, as she called him, vanish from her life. Perhaps that is why, however distressed Marshall was over Lady’s death, he appeared to have rallied by the beginning of 1992. At least, that was when he and Anna Nicole began to go public. Several months later, Marshall introduced Anna Nicole to his longtime lawyer, Harvey Sorenson, at a dinner at—where else?—the River Oaks Country Club. “She primarily talked about her career with Guess jeans,” Sorenson would later state in a deposition. By the summer of 1992, Marshall had, in Sorenson’s careful words, “made available for her use” the north Houston property—four or five acres of land, a barn, a workout area for horses, a swimming pool, and a single-family residence—that Anna Nicole would subsequently refer to as her ranch. In September Marshall bought another house in north Houston, a two-story contemporary where Anna Nicole made a home for herself and her son.

If the story is beginning to sound familiar, consider what happened next. In March 1993 $123.41 worth of Godiva chocolates and $358,958 in jewelry—precious and otherwise—showed up in Marshall’s Nieman Marcus charge account. There was a brief lull, then, one month later, the couple headed for Harry Winston in New York City. They arrived in the jeweler’s hushed Fifth Avenue salon at noon. Marshall was in his wheelchair, looking chipper. Anna Nicole’s happiness, no doubt, knew no bounds. As one salesperson explains, “She was allowed to pick out what she liked.” That included one 2-carat diamond ring (around $20,000), one round diamond ring ($46,000), one marquise diamond ring ($456,000), one diamond necklace ($493,000), one pearl-and-diamond necklace ($251,000), one diamond bracelet ($273,000), one pair of diamond earclips ($78,000), and one pair of pearl-and-diamond drops ($82,000). In the span of an hour or so, Anna Nicole spent about $2 million, including taxes. Marshall put everything on his platinum American Express card. “It went through in less than ten seconds,” the salesperson says. For Christmas 1993, he spent $293,000 more on jewelry at Nieman’s.

Perhaps Marshall doted on Anna Nicole to ease the pain of some unfinished business. The lawsuits he had filed in February 1992 against the heirs and several associates of Lady Walker, claiming that he had been fraudulently induced to support her, were still unresolved. Lady had left an estate worth $5.8 million, but because of the suit, the assets were frozen; her heirs had no way to keep up expenses, much less pay taxes on properties Marshall had given Lady. Faced with Marshall’s seemingly infinite resources and the zeal of his son Pierce, Lady’s family eventually folded their tents. Marshall settled with the heirs in the summer of 1993. Sources close to the case say he got almost everything back except Lady’s jewelry, the Sugar Creek house, and the house in Georgia. Lady’s Jaguar, Mercedes, Corvette, and two Rolls-Royces were posted for sale on the steps of the Fort Bend County courthouse. Marshall is still fighting Lady’s jeweler—refusing to pay a $500,000 outstanding balance—and her business manager. (They countersued, alleging tax fraud and defamation. But Marshall wasn’t cowed: Before the estate’s inventory was completed, his attorney suggested in a letter to lawyers for the estate that some of the jewelry was cubic zirconia rather than diamonds; his lawyer also intimidated the business manager by falsely claiming to have reported her to state insurance authorities.)

It may have been fortuitous for Marshall that, during this period, Anna Nicole Smith was learning that a celebrity’s upward trajectory can change direction. Yes, she had been offered some okay movie roles—parts in The Naked Gun 33 1/3 and The Hudsucker Proxy helped her land the Marilyn Monroe role in a remake of Niagara—and yes, she had been mobbed by thousands of delirious fans in Japan. But in December 1993 she was sued by a former publicist for breach of contract, and she subsequently settled in his favor; the following February she was rushed to the hospital, suffering from a drug overdose. The figure-revealing scarlet dress Anna Nicole wore to the Academy Awards last spring was much remarked on, mainly because it revealed that she was having a lot of trouble controlling her weight. Then, in May, she experienced the emerging star’s least favorite nightmare: a $2 million lawsuit by a former housekeeper. Among the charges: assault, battery, and sexual battery.

The accusations, replete with suggestions of drugs, hetero- and homosexual sex, and imprisonment, are curious and disturbing enough, given that the housekeeper is a Honduran immigrant who barely speaks English. But they also eerily mirror Marshall’s desire to have a controlling interest in another human being. “You had someone follow Maria Cerrato on at least one occasion,” alleges one legal document directed to Anna Nicole. “You told Ms. Cerrato that you loved her on more than one occasion,” it continues. “You told Ms. Cerrato that you wanted to marry her on at least one occasion.” Among other things, Anna Nicole Smith is depicted as a woman of unruly, insatiable appetites—of all kinds.

Perhaps it was the pressure of these events that drove Anna Nicole Smith to accept one of Howard Marshall’s increasingly frequent proposals last June. Or maybe she just loved him and sensed that his time was short. This is a Houston story, after all, and Houston stories, like Hollywood stories, tend to have happy endings.

Over time, some characters may disappear from the narrative, and others will undergo certain alterations. It’s started already: The dedication to Lady Walker that Howard Marshall had planned for his autobiography went instead to his second wife, Bettye, who is prominently mentioned in the book; Lady, who so craved acknowledgement of her status, is not mentioned at all. Marshall’s fortune is now safely ensconced in a living trust he shares with his son Pierce, whom he gave power of attorney last July, after the wedding.

It is possible to foresee a bitter struggle between Pierce and Anna Nicole once Howard is gone; she could, perhaps, wind up with nothing but a story to tell. But it is far easier to envision her at Anthony’s or the Rivoli or even the River Oaks Country Club, surrounded by an adoring entourage. She will be old, overweight, and overdone, her bust finally in proportion to her body. The semi-nude picture, autographed across her rear with the phrase “Remember Sweet Cheeks,” will have long disappeared from the wall at Rick’s. People will want to be with her, partly because she will be so rich—she will have endowed the J. Howard and Anna Nicole Marshall Center for Plastic Surgery at the Medical Center, the J. Howard and Anna Nicole Marshall Hall of Diamond at the Museum of Natural Science—but mostly because she will be utterly unchanged from her early years. She will have built a whole life without ever really caring what anybody thought—which is, after all, the Houston way.

As she told the viewers of her Playboy video way back in 1993, “In my wildest dreams I never could have imagined the good fortune and luck I’ve had this year. What could possibly happen next?”

- More About:

- Anna Nicole Smith

- Houston