The world of young-adult fiction is nothing if not slavishly imitative. Now that we’re well into the post–Harry Potter era, bookstore shelves are crowded with the stories of magical orphans with a destiny that are paced like Hollywood blockbusters, with fights, CGI-ready magic, and sudden revelations turning up like clockwork every fifteen pages. At first glance, San Antonio writer Rick Riordan might seem to be cashing in on this gold rush. A longtime middle school teacher who penned a series of modestly successful mystery novels featuring Texas private eye Tres Navarre, Riordan hit the big time in 2005 with The Lightning Thief, the first installment in his Percy Jackson and the Olympians YA series. Four books, 15 million copies, and one big-budget movie franchise later, he’s left the classroom well behind. Still, if there’s a whiff of calculation in his novels, it comes across as more pedagogical than commercial. The books don’t read as cynical but as the work of an enthusiastic teacher trying to instill in kids his passion for mythology.

Don’t get me wrong: For the first sixty pages of The Lightning Thief, Riordan is clearly working off the Harry Potter checklist—misfit kid of mysterious parentage, loyal nerdy friend, an institution for other magical kids, and the hint that he might be “the one.” The difference, though, is that unlike J. K. Rowling, who cobbles her mythos together from a variety of secondhand sources, Riordan draws on the mother lode of Western civilization, the pantheon of Greek gods and demigods.

Percy Jackson, the young hero of the series, is named after the Greek hero Perseus, and like his namesake, Percy is the son of a mortal woman and a god. In Riordan’s breezily dispatched exposition, we learn that the Greek gods have relocated over the centuries from one country to another as each has become the locus of Western civilization; Mount Olympus is now situated on the mythical 600th floor of the Empire State Building. Percy narrates all the books himself in the classic American idiom of the wisecracking kid—Holden Caulfield as demigod—and the various other figures are depicted with attractively comic American touches: Ares, the god of war, shows up as a leather-clad biker; the temptress Circe appears as C.C., the foxy owner of a high-end resort in the Bermuda Triangle.

Apart from these touches, though, Riordan plays it straight with the classic myths. The arch-villain of the series isn’t a pastiche like Rowling’s Voldemort, who is basically Milton’s Satan by way of Tolkien’s Sauron, but the titan Kronos, the father of Zeus. And amid the breathless pacing the author manages to sneak in some actual Greek history and culture: the definition of “hubris,” say, or juicy bits of mythological backstory. Riordan is also attuned to the myths’ powerful subtexts; Percy’s chief weapon is a magic pen, which at the touch of a finger becomes a mighty sword, an effect that no doubt strikes the teen reader as way cool but would also have had Freud smiling slyly around his cigar.

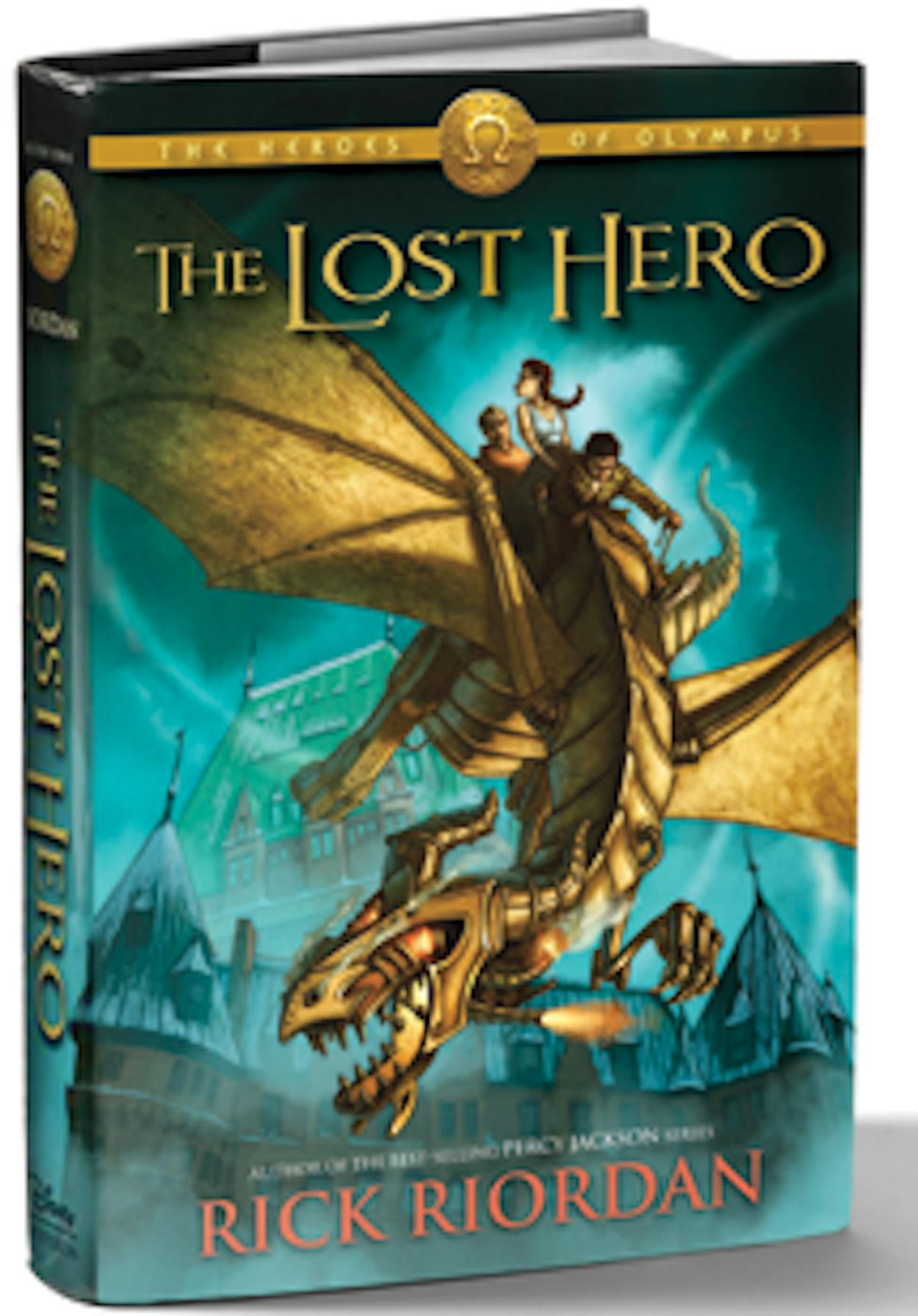

With The Last Olympian (2009), the series came to an end in a way that the Greek myths don’t but YA fantasy series invariably do, in an epic battle between the forces of good and evil. In the meantime, Riordan had become an international brand. February marked the arrival of a lame Percy Jackson movie, which predictably kept the fight scenes and largely ditched the explanatory passages. In May, Riordan started a new series, the Kane Chronicles, which does for the Egyptians what Percy Jackson did for the Greeks. And this month, he is releasing The Lost Hero (Disney-Hyperion, $18.99), the first volume of a Percy Jackson spin-off series called the Heroes of Olympus, which, judging from the two energetic chapters that his publisher is allowing reviewers to see in advance, is basically more of the same, this time featuring a kid with the rather significant name of Jason.

If Jason turns out to be a new version of the hero who stole the Golden Fleece, this choice will bring to the fore the nagging doubt adult readers may have about Riordan’s project as a whole, namely whether a contemporary YA series can do justice to ancient mythology. In the canonical versions, Jason’s story may start out as adventure, but it ends in tragedy, as a result of his marriage to Medea. The Greek myths were full of thrilling derring-do, but they were also full of murder, rape, incest, vengeance, power politics, and betrayal, among other non-kid-friendly things. While it’s true that most people learn about the Greek myths in childhood from expurgated sources—D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths calls the women Zeus variously seduces or rapes his “wives”—it’s also true that such versions don’t just leave out the good stuff; they fundamentally misrepresent the essential nature of the myths.

It’s also important to remember that to the ancient people who believed in these myths, the gods were both grand, in that they provided an explanatory narrative for the deep mysteries of existence and fate, and quotidian, in that ordinary people prayed to them for everyday things, such as a good harvest. When Riordan places these figures in a secular, pop-inflected world, he largely loses both aspects. Apart from some vague talk about the gods representing the spirit of the West, their battles in his books don’t impinge that much on the ordinary world; in fact, whenever the gods are around, a magical force prevents ordinary humans from seeing them in their true form.

It may be too much to ask a YA novel to engage fully with the dark riches of a three-thousand-year-old mythology, but there is a recent precedent: Philip Pullman’s magnificent His Dark Materials trilogy offers an intellectually sophisticated reimagining of Milton’s Paradise Lost, turning it inside out to create an atheist anti-Narnia. Pullman’s world is strange and beautiful and subversive, like nothing the reader has ever encountered before, while Riordan’s is an amalgam of books and movies that hew to the PG version of the myths. But perhaps this is unfair: Riordan is a gifted pop novelist, not a philosophical iconoclast with an ax to grind.

And Lord knows, the genius of the Greek myths is how protean they are. They have been put to infinite uses over the centuries, from the sublime comedy of the nineteenth-century German playwright Heinrich von Kleist’s Amphitryon to Ray Harryhausen’s Jason and the Argonauts. Bowdlerizing these stories may profoundly misrepresent them, but the originals will always be there to speak for themselves. On his website Riordan recommends books on mythology for young readers by Robert Graves and Bernard Evslin, and through them some of his fans will no doubt find their way to the hard stuff in Homer, Aristophanes, and Ovid. Riordan may not need to work in a classroom any longer, but he’s still dedicated to introducing children to the very foundations of their culture. Or as Percy Jackson might say, “Dude! These stories belong to you! Aren’t they cool?”

TEXTRA CREDIT: What else we’re reading this month

The Happiness Advantage, Shawn Achor (Crown Business, $25). A Harvard professor’s recent findings from the field of “positive psychology.” Read an interview with the author. Buy it at Amazon.

Comanche Sundown, Jan Reid (Texas Christian University Press, $29.95). A western novel about Quanah Parker and the freed slave Bose Ikard. Buy it at Amazon.

Bound, Antonya Nelson (Bloomsbury, $25). A novel of domestic turmoil inspired in part by the story of the real-life BTK serial killer. Buy it at Amazon.