This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

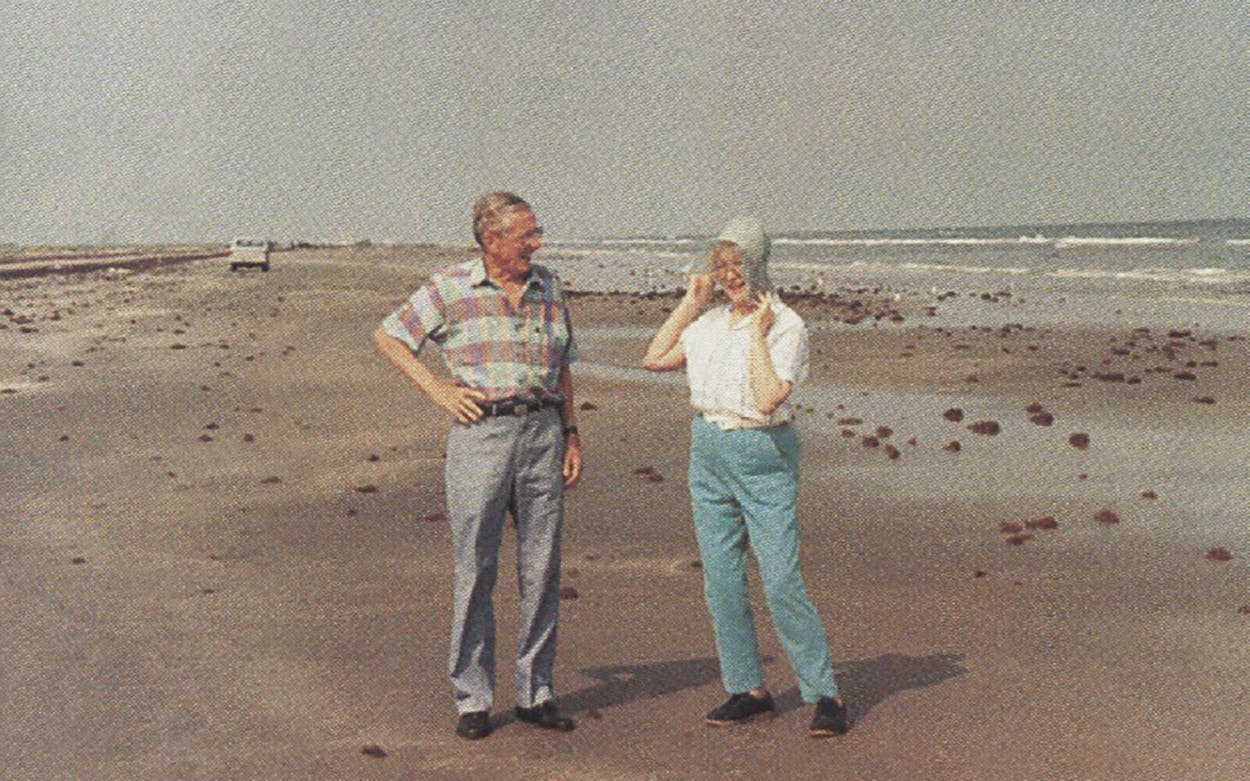

There is a poor snapshot of my parents I keep above my desk because it is the only one I have in which my father is actually looking at my mother. It captures a moment on a day that didn’t mean anything, a warm weekday in early spring. They are walking on the beach in Galveston. Daddy is in the brown leather shoes he ruined with cheap polish; Mama has on the clunky rubber-soled oxfords she wore even after her toes poked through.

Clumps of seaweed are scattered across the foreground, and tiny flecks that I presume to be gulls are picking through the wet sand. A truck is driving away in the background; otherwise, except for whomever held the camera, my parents are alone.

Daddy’s shirt is billowing in the Gulf breeze, making him look bigger in the gut than he ever was. His graying hair is cropped short; he cut it himself. His face is red, probably from the niacin he was taking. With a thinnish arm resting on his hip, he is laughing at Mama’s antics. She is squinting in the bright sun, bending awkwardly at the hip in an attempt to imitate a fashion model, and pulling on her blue straw sun hat with her pinkies extended in mock daintiness. The pockets of her turquoise pants bulge from her slightly paunchy body.

They could be anybody’s parents, except for what the photograph does not reveal. Mama and Daddy were never openly affectionate; they rarely even held hands in public. Who would have ever thought they could love each other to death? But that’s the bare truth of it: My parents were infected with AIDS.

The stigma of the disease was so unspeakably horrible to them that when Daddy died, he hadn’t even told his own brother what was wrong. Three years later, as Mama lay in the hospital near death, her dearest friends were still sending her cheerful cards that read “Hope it’s not too serious.” One of them, perplexed by her rapid deterioration, finally asked, “Is it cancer?”

The street where I grew up is a quarter-mile strip of wispy pines, anchored at one end by a water tower and punctuated at the other by a circle that finishes it, like the dot on an exclamation point. It is in Dickinson, halfway between Houston and Galveston but a thousand miles removed from them both. A lazy brown bayou trickles through the neighborhood. Instead of sidewalks, there are long grassy ditches.

Most of the residents, like my parents, have lived on this street for more than thirty years. Some are as close as family to us, but none of them could have guessed why Daddy summoned his four children home one Sunday in the spring of 1990.

From his tone on the phone, I knew the news would not be good. It was the same voice that once preceded squirmy lectures about sex or drugs or God. Daddy had been out of kilter since 1979, when Dickinson flooded and everyone on the street lost their possessions. But while the neighbors recovered, his bad luck continued. He caught hepatitis in 1982, was laid off from his accounting job in 1983, and never got his momentum back.

Not that he didn’t try. He earned a real estate license, bought a couple of Johnny Carson suits, and drove his dented blue pickup to Austin to work with an old chum who was a residential broker. By 1985, he was home again, selling insurance, sending out résumés, and picking up contract accounting jobs when he could. It didn’t help that weird things were happening to his body; he had colds all the time and frequent flus. After he became jaundiced in early 1987, doctors finally diagnosed chronic active hepatitis caused by hepatitis B virus, an infectious disease that can lead to cirrhosis of the liver.

Daddy told us his doctor had said hepatitis B was common among people who had been infected with hepatitis A, the form of the virus he had had years earlier. Although we didn’t question it at the time, this is not scientifically accurate; they are two separate viruses. Hepatitis B is spread like HIV, through transfusions, shared needles, and sexual intercourse.

Daddy spent nearly a month in the hospital, and when he came home, his equilibrium was lost. He stumbled all the time as if he had had too much to drink. He sometimes slept all afternoon.

My father was not a man of great tact; in his depression, he roller-coastered from moody silences to irascible crankiness about silly things. “Gosh, who’s playing that organ?” he bellowed one Sunday as he was walking out of church beside me. “She’s butchering that beautiful instrument!” A few minutes later, at my house, he continued, “Gee, when was the last time you waxed these floors? I’m slipping all over them in my socks.” It was hard to tell where the emotional pain ended and the physical pain began. His doctor blamed it all on the chronic hepatitis.

Some days, Mama’s patience wore thin, and I began to dread her phone calls: “It’s me. Do you have a minute to talk? I have a problem.” The calls were always the same: excruciating, long moments in which she would sob quietly and then say, “I shouldn’t be bothering you with this.” She was older than Daddy and wanted to retire from her job as a nanny; she was envious that he stayed home; she fretted that he didn’t tell her he loved her; she fumed that he was breaking his doctor’s orders, drinking wine and whiskey he had hidden in the pantry. Frustrated by Daddy’s malaise, she even accused him of laziness.

The real source of his problem was discovered in early 1990, but he and Mama waited a month to tell us the results. On that Sunday, Daddy prepared gumbo and Mama made her best lemon meringue pie. We ate nervously, making small talk.

Finally, feigning formality, Daddy said, “As you know, I’ve been going to John Sealy for tests. I tell you, these doctors, they’re not satisfied until they’ve poked and prodded you all over the place.” He propped an elbow on the table and rested his head in the palm of his hand, closing his eyes as he gathered his thoughts. He went through a litany of possibilities: They had tested his ears, his brain, his lungs; they had done CAT scans and spinal taps, looking for meningitis and cancer. Although his hepatitis was chronic, his liver functions were normal again. He cleared his throat before he said, “This virus has shown up, this HIV thing, like the one that causes AIDS.”

Mama was silent. To avoid our eyes, she folded and refolded her napkin, then swiped at the cobwebs on the light that hung from a chain over the table.

Daddy ran his spindly, veined fingers through his hair, rummaging for answers. Since he had been sick, brown splotches had appeared on his hands and arms. “I don’t know how much you’ve heard about it, but I brought home some information for you to read. There’s a fifty percent chance it could develop into AIDS. If it does, it’s terminal. I could live six months or two years.” He cleared his throat again. “You know, we all have to face Graduation Day. Mine is probably going to come soon.”

Graduation Day. It was an upbeat reference he had pulled from an old funeral sermon. He began to cry, and grief shook all the way through his body.

“Well, that means there’s a fifty percent chance it won’t become AIDS,” I said. I stumbled toward his chair at the head of the table and hugged him. “It’ll be all right, Daddy. Don’t cry—we’re here with you. ” My sister got up too. My family has never been physical; Daddy spent time in an orphanage as a child and was never comfortable being touched. He did not hug my sister and me back.

One of his tears landed on my hand. Suddenly it was a huge thing, the decision whether to wipe it off quickly or ignore it. My husband watched to see what I would do. It was the beginning of an issue between us, the debate over carelessness and common sense and compassion that arises when someone you love carries a disease that scares you to death. But I wanted to show my father that I was not afraid of him. I waited until I sat back in my chair, then wiped my hand under the table with a napkin.

We asked if Mama had been tested. To assure us she wasn’t infected, Daddy confessed a humiliating fact: He said he had been impotent for several years. Mama was adamant too; she was fine, she said.

Daddy quickly turned to practical matters. Since his health insurance had lapsed, he had enrolled in a University of Texas Medical Branch program that would help pay for the medicine he needed, including the expensive and potent drug AZT, and he had already applied for social security disability income, so we wouldn’t have to carry him financially.

Before we pulled ourselves away from the table, he said, “Let’s keep this in our immediate family only. Everybody doesn’t need to know our business.” Daddy took us into his office, pulled out a list of assets and debts meticulously drafted on a green ledger sheet, and reviewed every detail so we could help Mama with the paperwork when he was gone.

For our birthdays that year, my father chose four of his most cherished belongings and tearfully gave one of them to each of us: to me, the eldest, a pen set his brother had given him as a high school graduation gift; to my sister, the antique piano; to one of my brothers, his grandfather’s Stradivarius copy violin; to my other brother, a mosaic table he had made.

On days that he felt strong enough, Daddy cleaned closets, struggling to disengage himself from the material world. At night he and Mama prayed. My parents were devout Catholics with amazingly similar histories. Long before they met, in the forties and early fifties, Daddy had studied to become a priest; he left the seminary only because he developed stomach problems and couldn’t fast. Mama was a Carmelite nun for nearly a decade, until she suffered a nervous breakdown. It was a part of her life she did not discuss.

I had never seen my parents’ faith shaken, but it suddenly seemed as if Daddy were fighting the devil himself. He cavalierly threatened suicide, and Mama came home from work every day trembling, expecting to find him dead. When his disability payments came through, she quit her job to stay with him.

We were not involved with Daddy’s treatment. As long as he could, he drove himself to the clinic in Galveston alone. Near the end, Mama went with him. Every time he had what seemed like a symptom, we asked if he was still just HIV positive, whether his infection had developed yet into full-blown AIDS. He didn’t seem to know, or maybe he just didn’t want to say. The distinction is in the number of healthy white T cells still protecting the body’s immune system. HIV infection officially becomes AIDS when the T cell count falls below 200, because at that point the body is extremely susceptible to opportunistic infections. We didn’t know it at the time, but when he tested positive for HIV, Daddy’s count was already 49.

A lot of things about Daddy’s disease were confusing to us. He ached, but he couldn’t explain where. Because his mouth was sore and coated with thrush, he couldn’t eat; so he lost weight steadily, but otherwise, we didn’t see anything tangible to prove he was dying. There was just his continued bitterness and a black umbrella of despair.

But months later, when I was organizing family photo albums, I caught myself dating our history by the visible progress of his disease. In a snapshot taken a few months before he died, his coat hung off his shoulders, his cheeks had sunk, and the dance had disappeared completely from his eyes.

By then, he was so thin it troubled Mama to sleep beside him; he felt like a skeleton, she said. One morning, she was frantic. Daddy was too weak to climb out of bed. He was having accidents every night, bad diarrhea, and now he had a fever.

The emergency room at John Sealy Hospital, part of the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, is chaotic with charity cases. Sick old people and injured young ones vie for space on hard wooden benches, waiting hours to be seen. Daddy’s condition was bad enough that they took him to a bed quickly. He had a fungal infection; the doctors suspected it was invading his bone marrow. Days later, the fever was under control and he came home.

We took him back to the hospital three times in the next two months. The last time, we rushed home to find him curled in a fetal position, with his eyes closed, sucking air like a beached fish, in short, steady gasps. He wouldn’t respond to our questions. It was clear that he wanted to die. We called an ambulance.

Through the small window of his hospital room, we made out the beach in the distance. We had spent dozens of childhood Sunday evenings there with him and Mama, eating fried chicken and sand-gritty watermelon from the back of our pink Rambler station wagon, waiting for the sun to go down and the moon to come out so we could haul our crab nets in from the silvery water.

Daddy never saw the view. The infection had attacked his brain, and he was too weak to eat or drink. We knew what the doctor was going to say when he called us into the hall. He didn’t think Daddy would last long. With our permission, he discontinued all medication except for a morphine IV.

Daddy quickly descended from consciousness, but his rhythmic gasping persisted with the precision of a metronome. He was already like a thing not alive, just this emaciated, stubborn being that inhabited our father’s body. We took turns holding his sweaty, death-sour hands, humming softly “When the Saints Go Marching In.” It was one of his favorite songs.

On the fourth day, his fever rose to 107 degrees, enough to destroy his brain, and his kidneys failed. Several hours later, during a moment when all of us were uneasily absorbed in reading or studying, the gasps stopped. It was May 17, 1991, at 2:45 p.m.

Fueled by that hypersensitive stamina that kicks in after a death, we helped Mama get through the paperwork. Later, we found notes in the safe-deposit box for each of us. The familiar handwriting, the misspelled words, and the quasi-formal syntax made him seem as alive as if he had simply mailed us letters from a vacation. Mine said: “I love you Molly. Do enjoy the Pen set I gave you. I have treasured it these many years. Stay close to God and He will bless you for it. Allways Remember life itself is Terminal until Graduation day when you enter a new and better life. Prepare for it now, while you have Time. Daddy!” It was written on a kitschy Hallmark card that said “For the Graduate” on the cover.

For months after he died, I saw Daddy in my dreams, jovial and young again, with glasses too large for his face, peering through the dining room door, calling cheerfully, “Anybody home?” like he had done every evening for years, bringing surprises home with him from work in paper sacks: coloring books or pick-up sticks or tamales he had bought by the roadside.

Mama had a different vision. She woke up at night sweating, feeling Daddy still beside her in their bed. Something he had said once, when her sympathy hadn’t seemed sufficient, haunted her: “I hope you get this one day, so you’ll know what it’s like.”

The night’s torment usually subsided after her first cup of morning coffee. She busied herself around the house, discarding the oriental rug she had never liked, putting up frilly blue curtains, moving furniture. Mama began to look almost radiantly trim again; she shed more than twenty pounds.

For two years, my sister, brothers, and I had wondered about the extent of Daddy’s impotence, but we’re not assertive people; we didn’t probe. Instead, we watched Mama silently for symptoms, hoping the monster would never materialize. If she suspected that she was infected, she didn’t want to deal with it. Once, she had a bad case of the flu, and another time she had dark spots on her arm that she dismissed as sun damage. But now her weight loss was hard to ignore. After we pestered her to take an HIV test, she went reluctantly to the doctor. Her results were positive.

We were overcome with remorse for making Mama take the test, overwhelmed by the ominous uncertainties: How long would she be healthy? How long would she be sick? Would her death be horrible too? If we felt any guilt over our ignorance about Daddy’s treatment, here at least was a slight chance for redemption. We weren’t going to let her suffer alone.

Mama was particularly dependent on me because we had our own history. Before she met Daddy, not long after she left the convent, she was married briefly to another man. He was a Korean war veteran who had been blinded when a hand grenade exploded in his face. He was my real father, and he died shortly after I was born, in 1956. Mama’s sad, brief life with him was another memory she did not want unearthed.

She needed prodding when I went with her into the examining room on her first visit to an infectious-disease specialist. The doctor was a sturdily built, bearded redhead in his late thirties, with a gentle voice but a fair amount of practiced detachment.

He asked how she was feeling. “Fine,” she chirped. “I feel fine.”

“You’ve lost twenty pounds,” I said. “And what about those little spots on your arm?”

The doctor was straightforward: Her first T cell count was 325, which was good, but he was certain the HIV would develop into AIDS. He would prescribe a drug to prolong her quality of life. When she became ill, he would prescribe more and do his best to make her comfortable.

“But I’m not sick!” she pleaded.

“Yes,” he said, “that’s good. But there is no cure for AIDS. You’re sixty-nine years old. At your age, you won’t live more than five years.”

My mother had a way of saying “Oh, golly” that trembled with finality when she was resigned to something. She usually clenched her fists when she said it. “Well,” she added, “I won’t take AZT.”

Mama was never a willing pill taker; she had an aversion to even vitamins and aspirin. Daddy’s misery was still fresh in her memory, but her real hesitation was money. A month’s supply of AZT costs about $200. “I’m retired. All I have is social security. My insurance doesn’t cover drugs. I don’t know how I can pay for it,” she said, clinging to the examining table.

The doctor was firm. AZT was the only option. If she refused to take it, he would not accept her as a patient. He asked us to think about it and left us in the room alone.

There comes a time in every parent-child relationship when the roles are switched. I was already my mother’s caretaker, but after I helped her put on her blouse, I dug my head into her shoulder and cried. She wrapped her arms around me and trembled, saying, “Don’t worry, honey. Don’t cry, baby.” I promised I would find a way to help her pay for the AZT, and she conceded. On the way out, her cheerfulness restored, she insisted in befuddlement, “I don’t feel sick. I’m not sick.”

I’ve known other people with terminal diseases who put all their remaining energy into searching for alternative therapies. Perhaps Mama simply did not have that kind of hope. If an AIDS-related program appeared on TV, she left the room. She didn’t want to read about it either; articles I gave her about people who were surviving with AIDS were left buried under Better Homes and Gardens on the coffee table. We encouraged her to join a Catholic HIV support group. She went to two meetings, but the other members were all parents of gay men who had died.

Nothing about AIDS as it affected the rest of the world seemed to relate to her, so for two and a half years Mama dealt with her condition by refusing to acknowledge it. Desperate for diversion, she kept piles of needlework going, read romance novels, pulled weeds in the yard, walked the malls with her friends, took day trips with the church’s senior citizens. She even splurged on a few vacations to visit sisters and cousins in beautiful places she had never seen, like Colorado and Canada.

She made only a few concessions to AIDS: She counted out her four AZT pills each morning, and she grudgingly reported to the doctor’s office for routine blood samples every few months. When we asked, she would admit she suffered almost daily bouts of diarrhea, sinus headaches, and rashes. Like Daddy, she also had thrush. On top of that, she had ignored her mouth for years. She had contemplated spending the money to have an abscessed tooth removed and a bridge built, and her doctor advised her to go ahead. It was necessary to prevent infection, he said.

The experience gave her a bitter taste of AIDS prejudice; the first two dentists she called refused to treat her. As if the psychological trauma of the disease itself wasn’t enough, Mama found herself rebuked in even more unlikely places. The Sunday after basketball star Magic Johnson told the world he was HIV positive, the priest at the church Mama had attended for more than thirty years told the congregation that anyone who contracted AIDS got what they deserved. There was also a family problem we never told her about—a relative had told my sister that Mama was no longer welcome at her home for dinners.

Mama continued to live at home but spent a lot of time in Houston with my sister and me. She loved for us to take her clothes shopping, but fitting rooms became uncomfortable places after she dropped from a size 12 to a 10, then to an 8, and finally to a 6. “Look at these arms,” she would say, or, “Look at these bird legs. Isn’t this awful?”

We had a standard reply: “Well, a lot of people would love to be your size.” But we also huddled outside dressing rooms agonizing over her frail bones. By last summer, Mama’s once delicate, plump features were so wasted that she looked twenty years older. What we wouldn’t tell her, she saw in the mirror. She refused to pose for pictures anymore.

We did not talk about death. None of us ever seemed ready to discuss it at the same time. One night when Mama and I were alone together, she asked suddenly, “Do I look sick?”

Honest replies raced through my head. “No,” I said, thinking, “You just look old.”

“I feel good, I really do,” she said, as if she wasn’t entirely sure.

“As long as you feel good and keep a positive attitude, there’s nothing to worry about,” I said. It was like a script we had rehearsed a thousand times—about as often as I had asked her, during the last three years of her life, how she felt.

When Mama’s T cell count dropped below 200 last year, the doctor prescribed Septra, a toxic pneumonia preventative that many AIDS patients cannot handle; it knocked her flat with a high fever, and she had to be hospitalized for several days. He ordered another prescription to prevent infections when her count dropped below 100. This time, we asked about the side effects first: It would bring more diarrhea and nausea. When she asked my opinion, I told her to decline it. The doctor warned that without the drug, any infection she might catch could be life threatening.

Last winter, AIDS began getting the best of her. She started to tire easily. She stayed in bed through most of January with a bladder infection, her stomach swollen and rock-hard. She wasn’t eating or drinking much. Finally, we overheard her on the phone, admitting to her sister that she hadn’t urinated in three days. As we shuffled slowly through the hall to leave for the hospital, she took one last longing glance into each room of her house.

In the emergency room, Mama jolted upright, pop-eyed with terror, when a nurse inserted the catheter. It was beyond physical pain; it was her monstrous, exploding memory, Daddy’s ghost all over again, the final confirmation, the moment she finally realized that AIDS was going to kill her.

We took turns spending the days and nights with her in the hospital, adjusting with numb familiarity to the fluorescent atmosphere and hard chairs: picking at breakfast muffins she wouldn’t eat; hovering anxiously over her, looking for signs of death; helping the nurses turn her; pulling extra pillows out of the linen closet at midnight; wearing latex gloves every time we got near her; always washing our hands.

It is horrible, needing to wear gloves to tend your dying mother, just when you feel the need to touch her most. I tried to rub Mama’s chafed, dry skin with lotion, but the ill-fitting things bunched.

Her doctor wanted her to sign the order not to resuscitate, in part so he could release her to die naturally, at home. “Do you know where you are?” he tested her one morning.

She screwed up her face childishly, as if recoiling from a bad smell. “The hospital.”

“Do you know what year it is?”

“1972,” she said triumphantly, drawing out the “two.”

“Try again,” he grinned. When she didn’t respond, he prompted her. “It’s 1994.”

She seemed amazed. “1994. Is he really?”

“No, the year. It’s 1994.”

“My mother is 1994,” she smiled.

“Almost,” I said. Grandma was due to celebrate her hundredth birthday in a few months.

Knowing that my mother had the genes of eternity didn’t make things any easier. After two weeks in the hospital, she had received enough antibiotics to kill her infection four times over, but her low-grade fever persisted, and she had shriveled to less than eighty pounds—too weak to eat or even sit up in bed.

A hospice nurse named Cindy finally coaxed her to talk. “Ann, I know you’ve been thinking about dying. You’ve just been closing your eyes because you don’t want to face it. Come on, darling. You’ve been thinking about it, haven’t you?”

Miraculously, Mama opened her eyes. “Yes,” she said wearily. “I’ve been thinking about it for some time.”

“Well, let’s don’t hold it in. We need to get it out, now. Is there anything you’re worried about?”

Mama gushed, “I was worried about the house. And Molly, did you pay the taxes? And my car insurance is due . . .” Before she closed her eyes, she looked wistfully at each one of us and said our names. “I almost died the other night,” she said. She asked my sister to take her wedding rings, and said she loved us all. It was the last time my mother was truly coherent.

She had wavered over buying new bedroom curtains for months; so while the hospital readied her for discharge, we dashed to J. C. Penney, bought them, and hung them for her. We took her bed apart, vacuumed the floor, and picked flowers for her room. When her rented hospital bed arrived, we positioned it so she could see out the glass doors into her back yard, where pink tulips were blooming and the sun filtered softly through the trees.

Two burly emergency medical technicians brought Mama into the house on a stretcher. Cindy made sure she was comfortable before leaving my sister and me to share the bedside duties. Along with other supplies, she left us a sack of pills, all tiny enough to place under Mama’s tongue without water if necessary: one for restlessness, another for diarrhea, and the final one, the nurse said, was our “gold.” It was morphine.

With a morphine patch on her chest as well, Mama hallucinated wildly. Like a marionette with thrashing arms, she appeared to be picking magical fruit from a tree. Her glazed blue eyes were awestruck. “Will you look at that?” she kept saying, dreamily. “So there’s the devil who has been tempting all the women . . . Would you look at all those rats!” She was eerily composed.

It was a gruesome biology lesson, watching the body’s will to survive. Every day, we thought Mama couldn’t get any thinner, but she did. Every day, we thought she was going to die, but she didn’t. Unable even to swallow more than a few spoonfuls of water a day, she wasted to a skeletal essence, with thighs no wider than my arms. Her stomach was so sunken that her hip bones protruded several inches; we could even see the faint outline of her heart beating under her ribs.

My sister and I were feeling a little New Agey. We took turns reading Embraced by the Light, a sappy best-seller about a woman’s near-death experience, the kind of story you devour when you’re desperate. This may explain the vision I had the last night I stayed alone with Mama. It came at about six o’clock in the morning, when my brother peeked in her door. I was on the floor, on a mat, groggy because I had been up at four to swab her mouth. I heard the door open, but instead of my brother, I saw a beautiful woman with white hair, wearing a white coat. She floated toward the medication chart on Mama’s dresser. From where I was lying, I could not have seen through Mama’s bed, but I did. A rush of pure joy surged through my body. I knew immediately that it was Mama’s spirit.

Her breathing had changed; she was struggling, but she held on 25 hours more. Finally, at 7:20 a.m. on a Tuesday in February, she sighed deeply, smiled rapturously, and was gone.

The first time you lose a parent, things change but they don’t; there’s an anchor still connected. But when the second parent dies, especially if it’s your mother, it’s impossible to go home again, even figuratively. The rope binding you unravels and leaves you without the last person in the world who cherished your childhood more than you.

I keep remembering a moment last November when Mama called me, crying because my ancient grandmother had suffered a near-fatal stroke. “I know it seems crazy at my age, but I’ve always had my mama,” she said tearfully. I fought the urge to scream, “Well, you’ve had yours a lot longer than I’m going to have mine.”

I would like to think AIDS is no harder to deal with than cancer or car wrecks. Both of my in-laws have died recently of congestive heart failure. Yet while my husband has moments of sadness, he doesn’t go to sleep sobbing uncontrollably, as I do some nights. His parents were not burdened with private shame.

I do not honor my parents’ secret anymore; when people ask, I tell them the truth. But I am not an AIDS crusader. The disease chose us, that’s all.

Friends ask me if I’m angry, but I don’t know what to be angry about. For years we assumed Daddy was infected with HIV through a blood transfusion. I never found time until after Mama died to check his medical records; both hospitals that treated him now claim he didn’t receive a transfusion, and so much has happened since, none of us can recall those days clearly. We’ll also never know how he caught hepatitis B, although it most likely happened at the same time.

There’s a remote possibility that he was infected during visits to a public dental clinic in the early eighties. Still, I look at that photograph of my parents on the beach and wonder if Daddy could have been unfaithful. In bleak moments I even consider the unimaginable: that he could have been gay. According to his University of Texas Medical Branch records, he denied all known AIDS risk factors except for a transfusion many years back. Even if he lied, I don’t think I’m angry now; only saddened by the shortcomings of the human heart.

I’ve found prescription records suggesting that Mama had had a bout with the Epstein-Barr virus, which typically attacks people shortly after they have contracted HIV, in the fall of 1987, two years before Daddy’s condition was finally diagnosed. This much is certain: She had an incredible capacity to love. How else could she have married my biological father, scarred as he was, or even continued to sleep in the same bed with Daddy after he got sick.

When I look in the mirror, I see my mother’s high cheekbones, stubby nose, gnarled knuckles. Last week at my grandmother’s one hundredth birthday party, I saw other parts of her in her sisters: the unruly thin hair, once red; the small gray eyes; the square shoulders. It is a small consolation. I don’t want to remember how Mama looked when she died. Maybe that’s why she hasn’t appeared yet in my dreams.

We are not in a hurry to dig through her closets and divide her things. Her worn, soft nightgown is still hanging behind the door in her bedroom, with her homespun sweet scent lingering.

Molly Glentzer is a writer who lives in Houston.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Longreads