When my mother died last year, she left behind my 82-year-old father, whom, I have to say, I was extremely fond of but did not know very well. This situation had something to do with the typical American family structure of the baby boom years—Dad works, Mom stays home, kids vanish into TV land after six o’clock—and something to do with the peculiar structure of our own family, which I can best describe this way: A few years ago, I went to a lecture by a Jungian analyst, who urged us to map out our family as if it were a solar system. I drew an enormous sun with the rest of us orbiting around it, small planets at varying distances from my mother. Suffice it to say that since her death, the worlds have realigned.

If I didn’t suspect that this would happen, despite the warnings of mental health professionals (“Death changes the family dynamic”) and friends who gently advised that I read or reread Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (which actually has virtually nothing to say on this topic), I figured it out pretty fast. I was the one, after all, who had to call my younger brothers to tell them that our mother was in the hospital in San Antonio after an accident and it didn’t look good, and I was the one who sat with my son while a digital monitor ticked off the last seconds of her life. I was also the one who sat with my father in the funeral director’s office and composed a brief obituary on an enormous wall-mounted monitor, where every letter I typed lit up like an inappropriately cheery marquee (“W…e… w…i…l…l… m…i…s…s… y…o…u…, M…o…m”). In the process I became the family matriarch, a word I detested for a role I had never desired.

In those days—a blur even now—I spent more time alone with my father than I had in decades, planning the funeral, hanging out in the kitchen as people dropped in to offer condolences, and taking walks on those thick, late-summer evenings, as Dad escorted his arthritic corgi around the condominium grounds. There was a lot to talk about then, as there were a lot of immediate decisions to be made and a lot of advice to be deflected—“I have no intention of moving out of this building,” my father told me the night of Mom’s funeral, as if relocating to my home in Houston was immediately required—and at times I felt as if bits of my mother’s soul had entered my body, guiding me in the care and feeding of my dad. But something else struck me on those nights when we walked and talked under a navy-blue sky: Death brings gifts, I thought, and here was one.

Recent psychological research suggests that highly successful women had fathers who were very active in their lives, the kind who coached their soccer team or taught them how to negotiate babysitting salaries or looked forward to serial Indian Princess outings. But anyone who’s watched Mad Men knows that that kind of dad wasn’t around while I was growing up. My father was more comfortable with a book and a Scotch than with a crowd of PTA parents. When I was in third grade, he made me sign a contract that said I would never again require him to attend the Cambridge Elementary School Mexican Supper, and time hasn’t really mellowed him: When I was away a few years ago, my parents took my son to a Cub Scout function; my mother later confided that she worried Dad was going to stroke out during the (always) extended badge ceremony.

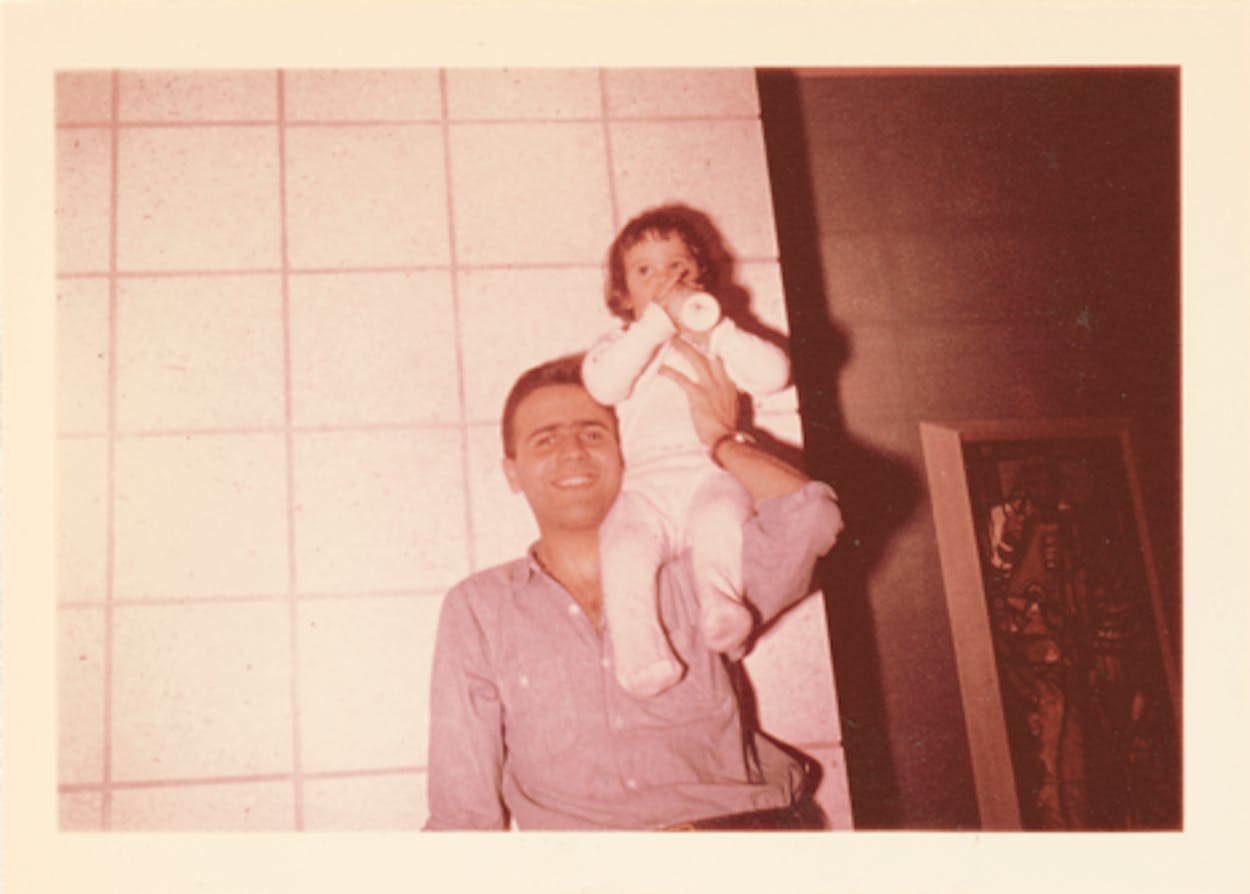

None of which meant he didn’t love his children or that we didn’t feel that love. When I was little, while the rest of the house was still sleeping, we spent early mornings reading the Sunday funnies, and each night, before I went to bed, he told me stories of Felix and Rasputin, a cat and a crow who shared daring adventures in Central Park. I have a memory of him swooping me up and dancing with me at a party when I was four or so and dressed in my very best—I don’t think I’ve ever felt more beautiful. On a Valentine’s Day some twenty or so years later, my father gave me a small heart made of twigs and painted scarlet. “You’re a daddy’s girl,” a friend who spied it said enviously. I looked up, surprised. The thought had never occurred to me.

Partly, this was an issue of definition. My idea of a daddy’s girl was all mixed up with my ambivalence about Texas; to be the apple of your father’s eye conjured in my mind a whiskey-voiced blonde who had her own monogrammed boots and shotguns and who even at twenty or so sat on the lap of her rich, red-nosed dad. My father was from Baltimore, worked in my maternal grandfather’s clothing store, and spent a lot of his free time volunteering in local politics, kibitzing with community leaders on the West Side. I was as proud of my dad as a daughter could be, but to behave like a Texan—hearty, expansive, sometimes boozily bathetic—would have required the breaking of my then Eleventh Commandment (“Thou shalt not act like Jett Rink”) and the piercing of my dad’s well-mannered, WASP-like mein. And too there was my mother, who could be so sensitive to any real or imagined slight that, my brothers and I liked to joke, she even viewed my father’s dog as competition for his affection.

So our relationship became, over time, affectionate but distant. When I was in college, he took to calling me in the early mornings from his office, a time of day when I was only semiconscious and a time of life in which I was far too self-absorbed to see that this was his way of keeping in touch. I grew accustomed to his penchant for indirection: On the morning after my son was born, Dad showed up in my hospital room just as the sky was getting light. I opened my eyes to see him sitting in a recliner at the foot of the bed, saying nothing but still, somehow, radiating joy. My mother told me later that they’d driven from San Antonio to Houston in the middle of the night because he simply couldn’t wait another second to be on the scene.

Of course it would have been my mother who told me that; she was the family interpreter. Maybe because of my father’s reserve or maybe because of her need to be at the center of things—both, probably—Mom ran the family like a switchboard operator: “Call your brother and congratulate him. He got a new job,” she would say breathlessly, no need to note that I had not yet heard directly from my brother. Or “Call your father. He’s had a bad day,” she’d say, explaining the causes in confidence, so that keeping track of what I was supposed to know and wasn’t supposed to know resulted in the kinds of polite, dead-end conversations more common to strangers on airplanes.

Still, I think my mother meant well—she kept us together, even if sometimes we joined forces against her—and for that and many other reasons, I don’t think my father ever stopped loving her for a minute. In my most generous moments I think, Why would he? If she was difficult, she was also exceptional, and as he told me in inconsolable agony on the night she died, “We were a team.” The last time I was home I noticed that he had taped to the wall of his bathroom an eight-by-ten photograph of the two of them at a party. The photo looks to be about twenty years old; my dad is in a tux and my mother is in a low-cut, velvet bodiced dress I know she was crazy about, and they are raising champagne glasses to someone or something important. They look as glamorous as movie stars. I have not asked him about the occasion, or even mentioned the photo, because sometimes it’s easier to operate the old way, avoiding tender spots as if they were potholes on a familiar street.

My mother was an expert at borrowing trouble, probably her best and worst quality. She could see problems looming long before they showed up as clouds on the psychic horizon—if, in fact, they ever showed up at all—and about a year before she died, she started worrying about Wesley, my father’s corgi. Wesley had the classic red coat, white chest, and assessing gaze of the breed, though his longish legs kept him far from any show ring. He also had a regal diffidence that could be laid at the feet of my father, who spoiled him far beyond anything his three children had ever experienced. Wesley, however, was approaching twelve and showing signs of serious decline. So it was that my mother spent some of the last months of her life happily searching for his replacement online, sensing, as she told me, that my father might be able to survive her death but she wasn’t so sure about Wesley’s. Eventually she became very enthusiastic about a tricolored corgi who lived south of Dallas, agreeing to pay for all shots and wait until the dog had a litter and was spayed to take possession. It was like being involved in a private adoption.

Unsurprisingly, within days of my mother’s death, my father became laser-focused on journeying to Dallas to meet Trilby, perhaps perceiving that in this case my mother’s dark predictions about Wesley’s numbered days and Dad’s subsequent mental state were correct. “Have you called Dee? Let’s call Dee,” my dad would say, rapping me anxiously on the forearm. In fact, I had by then exchanged several phone calls and e-mails with Trilby’s breeder about our upcoming visit, and I was beginning to worry that the hint of desperation in my voice might inspire her to look for a calmer home for her dog.

At the time I was in high monitoring mode, a characteristic common to oldest daughters in the best of times and which then seemed like a handy way to avoid my own grief. When my father complained of foot pain, I took him to Mom’s acupuncturist, a grave-faced doctor from China, who scheduled my father for a series of treatments I knew he would never show up for. We tried new restaurants, because the old favorites were sometimes too painful. (They made my eyes fill, because so many of the waitresses knew my dad by name and, having somehow heard the news, greeted him with outstretched arms.) I attended Dad’s dog group so that I could surreptitiously get the e-mails and phone numbers of the members for surveillance purposes, and I went to dinners with some of Dad and Mom’s widowed or divorced friends, trying not to picture them as the Casserole Ladies friends had begun to warn me about. (“As long as he doesn’t get married, it’s fine,” one of my friends told me, a piece of proactive advice that came a little too early for my taste.)

In general, I worried over how much of my mother’s role I should take on. A few weeks after she died, Dad told me he was going to an anniversary party for some longtime friends. I had the impulse to question the plan—wouldn’t that experience rate pretty high on the self-inflicted-pain scale?—but I didn’t, and when Dad later admitted he had fled after just a few minutes, I pictured him alone, surrounded by the still happily coupled, and agonized at my error. Mom would have squelched the idea in seconds, and none too graciously to underscore the point, but I hadn’t thought it was my place to do so. When I was raising my son, I had to learn to get out of his way so that he could thrive—to stop helping too much with homework, to stop hovering, to stop manning the barricades every time some mild threat arose that might interfere with his otherwise flawless childhood. Now I was in a landscape that was new but old at the same time: My father was elderly but not infirm, and once again I found myself in a balancing act between meeting a loved one’s needs and respecting his independence. “I’ll meet you for coffee when Dad goes down for his nap,” I told a friend, still getting my bearings. Sometimes, talking to my younger brothers about Dad feels like herding cats (“Have you talked with Dad recently?”), and I hear in their responses a faint replication of the tight tone they—and I—sometimes used with Mom. But I see things from the other side now, and if that isn’t exactly grace, it is certainly a path to understanding I’m grateful for.

Gratitude is what I felt as well when Dad and I drove up together to get Trilby last October. I was past the most intense grief by then, paying late bills, catching up on assignments, and reconnecting with my husband. But I took the day off for the expedition. It was something of a white-knuckle drive because Dad, oblivious to the speed limit, wanted to make the round-trip in one day. Still, fall was coming and the air was cool and the sky was clear, and when we got to the kennel, Trilby performed several high-speed loops around her barn and then hopped in the car as if she had been waiting all her life for us. She is a beautiful dog, with winglike ears and a flouncy rear that rivals Beyoncé’s; even Wesley couldn’t complain when we introduced them, acting instead like a pasha receiving a new concubine.

Dad and I stopped at the old Stagecoach Inn, in Salado, for a late dinner. I had stayed there a zillion years ago on the Fourth of July, with Mom, Dad, and my brother Jeff—my younger brother Ed had not yet been born—and my parents’ friends the Shands and their children. As night fell we kids played with sparklers and pill bugs while the grown-ups drank beside the pool, and I’m sure it was the kind of easy, happy night where no one gave a thought to the ends of things, much less new beginnings. There was just, maybe, a warm breeze that tickled the grass, bending the tops but leaving the stalks intact.

Early this spring, my father called me with an apologetic tone. “I’m in the hospital,” he said. It wasn’t the heart attack he’d thought it was; he’d pulled a muscle in his shoulder, which resulted in serious pain close to his chest. His friends Luci and David had taken him to the emergency room and stayed with him until I could get to San Antonio. The doctors kept him for a few days for observation, which gave my father time to befriend all the nurses and me time to recover from the scare. The cardiologist showed me images of my father’s heart pumping while he reviewed the results of Dad’s EKG. “For an eighty-two-year-old man, he’s in great shape,” he said, the qualifier being the important part of the diagnosis, of course.

And so we resumed our routine. Dad comes to Houston some weekends; other times my husband and I go to San Antonio. There is always an absence in either place, but we fill it with chatter about Trilby or the antics of the people on his condo board or some talk about the governor’s race, because that is what survivors do. This is the way people connect or reconnect, knitting together the hundreds of small things that make up our days. “Mom would have left after five minutes,” I told Dad, family shorthand for the fact that a weekend party had been unpleasantly loud. “Your mother always loved figs,” Dad said, tasting the first of the season. Wesley died a few months back, and it was tough, but my dad got through it. A few months later, he was looking into plans to donate a water fountain at a local park. “You could name it in Mom’s honor,” I said. “I was thinking about naming it after Wesley,” Dad said.

I am now my father’s date of choice for funerals, and though I can’t say it’s a pleasure, it’s instructive. My mother’s longtime frenemy died a month or so after she did, and during the service I joked to myself that this was probably why my mother was never much interested in an afterlife—I could see the two women one-upping each other into eternity, and it wasn’t pretty. At another I sat under a huge live oak with Dad and listened to long, eccentric eulogies that were as much about a disappearing San Antonio as the person being mourned. Most of the time, too, there are the daughters, putting out sweets, straightening rows of chairs, steadying a surviving parent. They are women I’ve known all my life; their faces are lined now and their waists are thicker, but when they smile in recognition, I see the girls I used to know. We hug each other, genuinely happy to share the moment, starting over on a brand-new day.