Austin, April 2007

Mu Naw stood on the landing above the airport baggage claim area at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport and wished she had on different shoes. She shifted the plastic International Organization for Migration bag from her left shoulder to her right and grabbed her daughter’s hand. There were two escalators leading down; she and her husband, Saw Ku, had instinctively paused, not sure which one to take. People passed them on the right and left, confidently moving through space as Mu Naw never had. Mu Naw’s shoes, the black rubber slide-on sandals everyone used in Mae La camp, felt dusty, undignified. She was proud of her skirt and shirt—these were her nicest clothes. They were red and handwoven in the traditional Karen style, a long straight skirt with braided fringes brushing the top of her feet, a tunic with a diamond-shaped hole she slipped her head into. She looked at her daughter Naw Wah, who was two, in her pink Karen dress, and her other daughter, Pah Poe, who was five, in a turquoise one. Even Saw Ku, holding Pah Poe’s hand, had a green tunic that he wore with jeans. In the tiny airplane bathroom, Mu Naw had rebraided the girls’ hair, and Saw Ku had slicked his hair down with water from the tinny sink.

She had heard from friends at the camp that she would get a black sweater and new shoes on the bus to Bangkok. There had been no shoes and no sweaters, though Mu Naw had looked behind the bus seats to make sure. She was too shy to ask the UN workers at the time, but she had not stopped worrying about her rubber sandals in every airport, afraid they seemed shameful to the IOM worker guiding them, that the lack of new shoes meant that she had missed some important step everyone else knew that she did not.

Now the IOM worker was gone. That was another piece of information they had heard in the camp, this one accurate: They would know they were boarding their last flight because the IOM worker would not go with them. Mu Naw had barely known the woman, but now felt bereft without her.

That woman had been certain and knowledgeable, guiding them through their travels by reading the long lists of names on huge signs overhead in each airport and then translating them into their native dialect, Karen, from Bangkok to Los Angeles. Mu Naw could read several things in English already, but she could not understand why the large A22 meant you were on a flight to Dubai, and A23 meant you were going to Hong Kong, but A24 meant Los Angeles. It was one of thousands of things Mu Naw did not grasp.

Mu Naw’s entire life had been spent with people who looked like her. Occasionally, a white UN worker or volunteer came to the camp, but that was it. Everywhere she turned were people with different eyes, ears, hair, noses, clothes, skin, mouths, purses, hats, hijabs, necklaces, bracelets, wallets, suitcases, books, food, water bottles, headphones, scarves, pillows, sweaters, shoes. Even when her eyes were down to shield her from the onslaught of strange sights, the languages assaulted her ears, snatches in tones she had never heard, musical, guttural, loving, rude. The smells of perfume, food, sweat, air-conditioning kept her from breathing in deeply.

Now, in Austin, standing in her last airport at the top of two escalators going down, she wished desperately for one brief minute that they were back in Mae La camp. She wished the IOM woman were still with them. She wished she had her new sweater and shoes.

They had only seen an escalator a handful of times, most of them in airports within the last twenty‑four hours. She turned and gazed blankly at her husband for a minute. Saw Ku walked to the escalator on the left, almost running into a white businessman pulling a suitcase behind him. Mu Naw fell into place behind him. She stumbled for a minute, eyes down to keep her balance, clutching the rail that made her hand move slightly faster than the stairs on which she stood. She made sure Naw Wah’s tiny feet were centered in the metal striped step. When she finally reached the bottom of the stairs, anxiously avoiding the steps submerging into each other, Mu Naw took a firm step with Naw Wah over the line that ended the escalator, then looked up. She didn’t have time to worry; a man was already greeting them in Karen, standing beside a tall white woman with a wide smile.

“Are you Saw Ku and Mu Naw? We’re here to take you to your new home! Welcome to Texas!” Mu Naw’s face broke into a relieved grin.

The white woman and Karen man helped Mu Naw and Saw Ku get their bags from the revolving circle that spewed luggage out of a large metal mouth. Their bags were easy to spot: multicolored plastic zip-up bags they had purchased from a store in the refugee camp. Just a few days before, Mu Naw had approached a hut where the owner had opened the front wall to form a makeshift storefront. Rusted shelves held snacks and sodas, soap and toothbrushes and combs, rubber sandals in dusty plastic sacks, and a rotating inventory of whatever items he could sell. The store owner’s children watched, squatting in the front of the store, their cheeks white with thanaka to protect them from the sun. Mu Naw tried not to smile too broadly when she walked up and asked the store owner respectfully for the Western bags. He turned and rummaged through the back of his hut, his children looking on solemnly. He handed her two, asking her where she was going.

“Taxi! We are going to go live in Taxi!” He nodded in response, as if he knew exactly where Taxi was. It would be years before she would realize the difference between the yellow cars you could hail on the street and the state where she lived, or laugh at the fact that she had confused the two.

Mu Naw held the bags proudly slung on her shoulder back through camp, deftly jumping along the uneven packed dirt paths, up the hill lined with huts on large bamboo stilts, past the concrete bathroom area with the trickle of water where everyone—women on one side and men on the other—bathed discreetly, covering themselves with longyi while they washed. Her neighbors eyed her. A few friends waved. The large square bags were a symbol of the trip she was taking, of her new status in the world. She had seen others walking with those bags before they disappeared from the camp forever.

The camp where she had lived in Thailand, Mae La, was supposed to be a temporary stop. After the infiltration of Laotian and Hmong refugees on the eastern border of Thailand in the 1970s and 1980s, the country had very little patience for the refugees arriving from Myanmar on the western border. Thailand had remained stable in spite of war in Vietnam, genocide in Cambodia, unrest in Laos, persecution of Hmong people wherever they lived in the region. The longest-running civil war in the world was not the problem of the Thai people. They designated land where those who crossed illegally into the country could live in ramshackle huts, packed together like pickled fish in a can. Mu Naw had not spent her entire life in the camp; she was unusual among her generation for that. Many of them could barely remember life in Myanmar and most left the camp only by sneaking out and avoiding roads with Thai police or military officials. Leaving the camp was illegal, and capture usually meant being returned to Myanmar. They lived cheek by jowl together, until rumors spread through the camp that doors were being opened for them in other countries. UN officers interviewed them, suddenly interested in their stories, verifying again and again that they were refugees—of course they were, why would anyone live here if they could live anywhere else? More officials came, from Canada and Sweden and Australia and the United States. Mu Naw stood outside the community center beside the dirt road, jostled by what felt like half the camp, when the first two groups of Karen people boarded rickety buses, everything they took with them in their coveted colorful bags. Everyone wanted to wave good-bye, to witness them actually leaving. Mu Naw waved and teared up when one woman wailed, watching her daughter and young grandson wave good-bye through the bus window. But she also felt a rush of excitement as the bus wheeled away in a whirl of dust and exhaust.

Their empty huts were now fair game—daughters‑in‑law living in one room with their husbands’ entire family moved happily into an abandoned hut down the row. But Mu Naw didn’t even try. She knew as soon as she saw the first group leave that she and Saw Ku would go. There was no life in this camp.

When it was her turn, she and Saw Ku were chosen to be among the first groups to resettle in the United States from Mae La. Her Buddhist mother called it luck; her Christian mother-in-law praised God’s hand in the UN selection process. Mu Naw thought perhaps it was a bit of both. There were thousands of people in Mae La camp who would give anything to be her, walking purposefully past her neighbors with bright plastic bags on her arm.

When they rounded the corner on the baggage carousel, Mu Naw was surprised that the bags that had felt foreign and new just days before now seemed intimately familiar, as if they had been with her all of her life. In her IOM sack, tucked inside her own woven bag, she had her passport and her daughters’ passports and the important documents they brought with them. In the checked bags, they had packed what was left: T-shirts, tunics, and two pairs of jeans for Saw Ku, woven tunics and skirts for Mu Naw and the girls, a few extra for them to wear as they grew. There were albums with pictures of each of their relatives, a jar of thanaka for the girls’ faces, cream for Mu Naw’s skin, a few clips for their hair, underwear and combs and toothbrushes. And that was it. There was nothing else to take.

Seeing their bags, Mu Naw felt a pang for the box of letters she had left behind. Two days before she left, she found a tree near enough to her hut that she could find it again someday but far enough away where it would not be disturbed by her neighbors. She had dug a small hole in the hard clay dirt and placed a tin box near the roots of the tree. In it were all of the letters she and Saw Ku had written to each other over the months when they first admitted they liked each other when they were fifteen, saying on paper what they were too shy to express out loud. She had thought about taking the box, but she was not sure what would happen in their new place. This camp seemed more constant, more real than the fantastical new life she would lead in America.

As she watched the white woman and Karen man talking to Saw Ku about the bags, at the end of an exhausting journey that spanned endless, monotonous hours, Mu Naw suddenly knew with a deep certainty she had made the wrong choice. She had thought she would go back with her daughters to dig up the letters in a few years. The idea of ever returning now seemed impossible; the English that had been a novelty spoken only by UN workers now engulfed her. The loss hit her in a powerful wave of grief. She could close her eyes and see the sun shining through the expansive green leaves of the tree, feel the muggy air on her skin, the claylike dirt beneath her sandals. It was perfectly clear in her mind but the tree was on the other side of the world, standing vigil over the teenage love she had shared with her husband; the tin box would rust, the letters disintegrate. Her daughters would never read them. She moved forward numbly, feet shuffling on the cold linoleum.

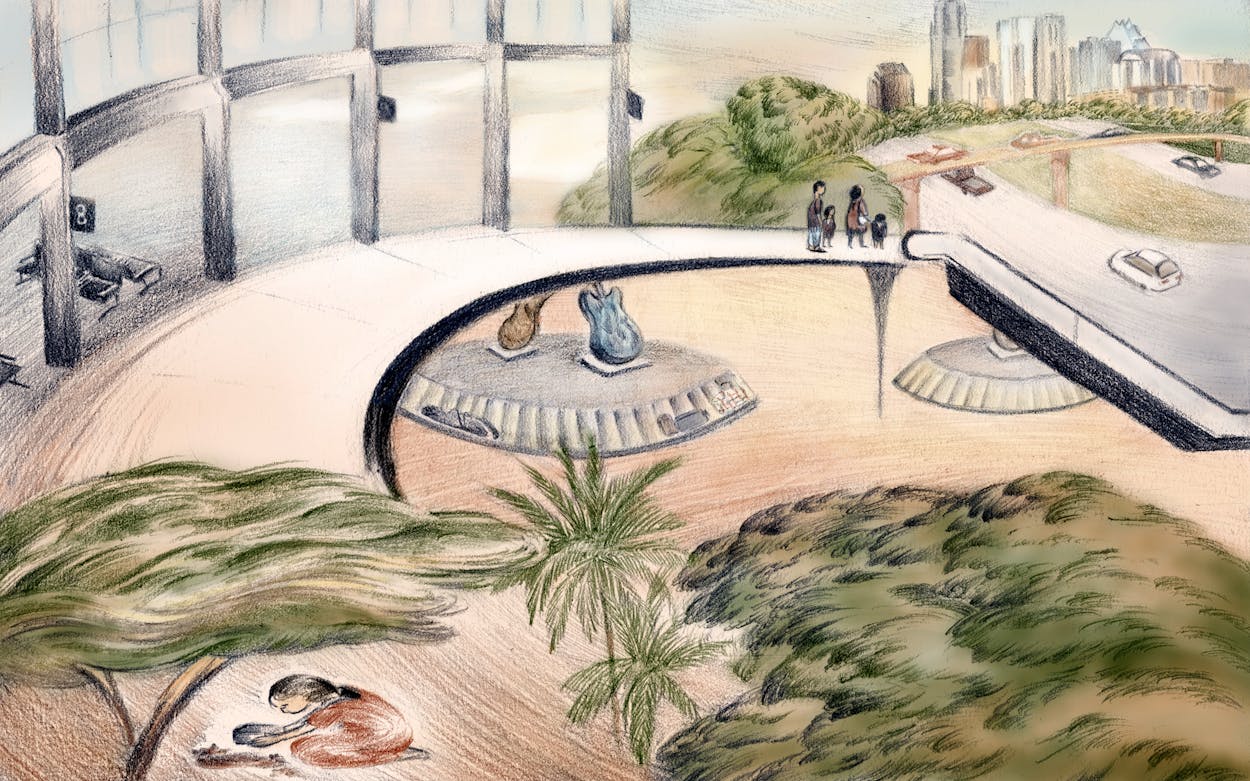

The car ride from the airport to their new home was a dizzying, exhilarating experience. They had walked on a crosswalk where cars paused politely. The white woman led them around to the side of a dark van and showed them how to buckle their children into the car seats. The children slept, mouths open in exhaustion. They skimmed the smooth highway into town, the lights and buildings whizzing past at a rate that left her dazed. Mu Naw gripped the armrest, body hunched against the window in an effort not to throw up or cry or succumb to the powerful emotion she could not name that pressed down on her. She had only ridden in a car a handful of times in her life and it was nothing like this, the flight of an efficient machine through an electric landscape she had never imagined existed.

They parked their car in a circle of light under a street lamp at an apartment complex with iron gates that were open. The air smelled like asphalt and clean laundry. The white woman and the Karen man took their bags and led them to an apartment on the first floor with a faint hint of cigarette smoke.

The lock on the door stuck for a minute, but then they got it open and walked into a living room with a brown couch and a chair, some empty shelves, a tall floor lamp leaning slightly to the side. There was a table in the small kitchen, appliances on the counters, a refrigerator that whirred gently. In one bedroom was a large master bed with a red and white comforter. The other bedroom held two twin beds covered in white comforters. The sheets were already on the beds; the woman showed Saw Ku how to lock the door and put up the brass chain that would keep everyone out. She made him try several times, watching until he got it. The children slumped on the couch, staring at their father opening and closing the door and fastening the chain.

Finally, they started to leave, the Karen man translating for the white woman that a church group had gathered all of this furniture for them, that everything was theirs to keep, that the refrigerator had some food in it. He added that the group had prayed over the apartment, a fact that pleased Mu Naw. They smiled warmly and Mu Naw tried to speak her new language, her “thank you” a bit garbled, but the woman understood and, after an awkward second of jostling, they hugged. Mu Naw barely came up to the woman’s shoulder. The Karen translator repeated his invitation—they would come eat dinner with him later that week. After they left, Saw Ku hastily locked and chained the door. No one mentioned when someone would be back to get them. They didn’t think to ask.

They looked at each other and smiled. This was it. They were here. They dug through the bags for squashed, wrinkled pajamas; when Mu Naw unfolded them, the scent of wood smoke, clay floor, dried bamboo rushed past her. They brushed their teeth in the bathroom where the water ran inside the house any time they wanted. They tucked the girls into the large queen bed between them, a little unit of four.

As she crawled into the bed beside Naw Wah, Mu Naw imagined getting ready to sleep in their small hut in Mae La camp, laying out the mats, pulling the mosquito netting away from the wall, fastening it around them. The leaves in the trees outside would rustle; their neighbors’ conversations would seep muffled through bamboo walls until the thick night settled around them. The rice mat would smell pleasantly like earth; it would be flat and cool.

This new bed was soft. The sheets were stiff and held the crisp wrinkles that Mu Naw would later know meant they had been unfolded from a package. The blanket was thick. The blinds above the headboard gapped slightly at the bottom and the light from a street lamp shone through the meager tree outside her window, forming shadows when the wind blew that made her jump. The white noise of the nearby highway was a motorized river, the constant stream disrupted by horns or loud engines. She could hear voices outside the apartment speaking in a language that did not sound like English, voices that spiked into an argument in the middle of the night. She lifted her head to see if Saw Ku was awake; he lifted his head too. He silently reached over their girls and took her hand.