This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On or about April Fool’s Day, 1953, a slender young man of some Choctaw blood twisted in his saddle, grinned back at his trackers like a young Charleton Heston, then reined his stolen horse through the snipped barb-wire and disappeared into the Texas twilight. At least, that’s the kind of image some people have of Charles Brogdon today.

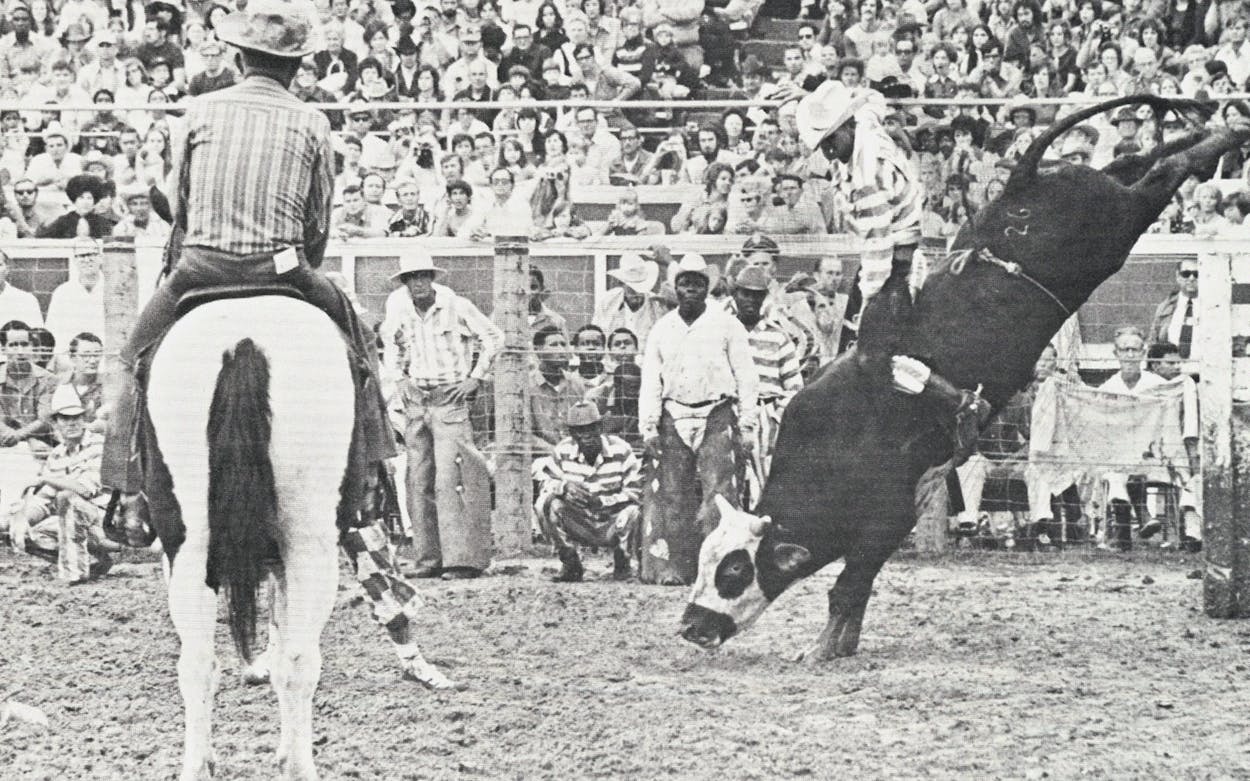

Twenty years later, Brogdon is almost gaunt in his slenderness, his cheeks are sunken and creased like those of so many a working cowpoke, and he’s punching milk cows for the Texas Department of Corrections. While he was inside this time, Brogdon got himself stabbed 45 times by another inmate—it took a year for his lungs and liver to heal—and a year ago he rode the bulls and saddle broncs well enough to finish second, at 39, in the overall point-standings of the Prison Rodeo at Huntsville. He’s been transferred now to a minimum security unit in the sweltering flatlands west of Houston, and he’s due out in November. No guns, no dogs to take him to work, no fences, no electric-locking gates. Brogdon fiddles in the saddle shop when he’s not working cattle, and except for his prison whites he looks like any other ranch hand. His warden is a proper but pleasant black man; the warden’s office neighbor is a representative of the Texas Employment Commission. In a few months Brogdon will be just another ex-con facing the intimidating prospect of freedom, trying to forget the wife that divorced him the second time they sent him up.

Except this ex-con’s a little different. There was this stunt he pulled up in the hill country when he was 19 years old. All the old-timers around Kerrville, Medina, and Bandera remember him, and the expatriate San Antonio newcomers hear about him as soon as they arrive. His story has now passed into the second generation, and it gets better all the time:

“Well I heard he did it on a dare.”

“How many Rangers was they in that posse?”

“I heard he shot those bloodhounds right between the eyes.”

“The radio was hot all day, telling where he’d been seen. They’d spot him at Ingram and thirty minutes later way up in Rocksprings. The first thing you know he’d be over at Leaky, all on foot. He could really cover the miles.”

“Hell, I heard he did the same kinda thing ten years later. They say he greased himself down and broke jail over in Rondo, and off he went again.”

“Well I don’t care what you say. He was a nice young fella as far as I could see, and he sure gave those Rangers a fit.”

On and on and on: The story has been passed, dropped, and thrown into so many hill country conversations that by now the deed far transcends the man. The quiet man in the pre-release center outside Sugarland is at once Charles Brogdon, the two-time loser; and the See More Kid, the State of Texas’ last great Romantic outlaw.

Brogdon was born in San Antonio but he grew up in the Valley outside of Mission. His half-Indian mother died when he was five, and his father was away much of the time, peddling livestock pills to feed stores. Brogdon got into juvenile trouble early, landed his first ranch job at the age of 15, and in the spring of 1953 he was working for a German rancher near Fredericksburg when one day he just went off into the woods alone. “I was sorta tired of things,” he says now. “I wanted some solitude.”

But the kid was apparently unwilling to do without some of the finer things in life during his hermitage. After several weeks in the brush he was wanted in connection with 40 residential burglaries, six cut fences, two stolen horses, and one stolen jeep, which he allegedly rolled. You know how cowboys drive. He killed a deer or wild turkey for food occasionally, but he also broke into summer or weekend homes, raided the pantry, washed his dishes, showered, and slept on a mattress for a change. He didn’t take much and he usually left things in order, and the law officers in the area let things slide for a while. But then in late March they decided enough was enough and approached Bob Snow, the best on-foot tracker in that part of the country.

Snow is a widower whose son is foreman of the Y-O, a sprawling converted sheep ranch in Kerr County that now runs exotic game into the sights of hunters who can afford the price of a guaranteed trophy. He is a retired game warden and Tex-Mex translator for the Texas Rangers, and he has a reputation as one of the windier raconteurs in the state. “If I ever take a hand in writing another book I’m going to run the whole show,” he told us. “I did most of the work on one a few years ago and all I got out of it was some overlasting gratitude in the first chapter.”

However, Snow couldn’t tell us much about the See More Kid episode. “I refused to participate,” he said. “My wife’s health was getting bad, and I didn’t feel like I ought to leave her. And I didn’t want to kill a white man.”

When the best on-foot tracker in the country turns you down, there’s not much you can do but call in the Texas Rangers. L. H. Purvis draws a state pension now and works as a special investigator for the Kerr County Sheriff’s Department, but he was then the Ranger in town. We approached Purvis for an interview but he said, “That wouldn’t make a very interesting story.”

Nonetheless, Purvis is the man who organized a posse of around a hundred men, horses, dogs, and Piper Cub pilots. For a week Brogdon led them on a wild, circular chase through the hills, and when he got tired he simply broke into another house, fixed himself something to eat, and lay back for a while. After a week of hearing about himself on the radio Brogdon began to scatter the contents of the lodges around, and at each scene of the crime he left provocative notes, many of them directed to Purvis. “The See More Kid sees more and does less,” one of them read. “I hear the Rangers coming and I’ll have to go play hide and seek.”

See More almost got too casual the night of April 4. He was taking it easy in Wallace Canyon—a beautiful ravine enclosed by 200-foot bluffs between Kerrville and Medina—and as the San Antonio Express reported the next day, “When officers approached the house, leading four blood hounds, they surprised the youth sitting at a table in the burglarized home. He had just taken a bath and was eating a sandwich. He ran out shooting. Three of the dogs dropped and a fourth refused to continue.”

Brogdon maintains the officers were the ones doing the shooting, and he says they unleashed eight bloodhounds on rancher Jep White’s land, not four. At any rate, Brogdon head-shot three of them with a borrowed .22 pistol, a feat of marksmanship not lost upon his trackers. The posse nevertheless thought they had the Kid trapped, but the Express reported a day later, “The hungry and hunted terrorist of the hill country struck again Monday [at a site 15 miles removed from Wallace Canyon]even as more bloodhounds and Rangers were brought into this area in an effort to bring him into custody.” Brogdon had reached the top of one of the cliffs with the aid of an oak tree and left the posse stumbling in the darkness below.

“I wasn’t scared he was gonna hurt anybody,” Jep White told us. “And he didn’t. He never did bother us—but he scared all the women to death.”

In some cases. Down Highway 16 from Wallace Canyon a couple approached their home with their grandchild and saw a familiar stranger in the doorway. The man splashed across the creek and ran yelling for help; the woman took the child inside and fixed Charles Brogdon some supper.

Purvis was footsore and suffering from lack of sleep by then, and he was catching a lot of flack in Kerrville. The genuinely concerned wanted to know why he hadn’t caught that hoodlum, and the irreverent thought it was a high old time. There was a post-office wit nicknamed Roadrunner in town then, and he reportedly approached Purvis one day and asked, “Hey Ranger, what’s that boy done that’s so wrong?”

“He killed some valuable dogs, for one thing.”

“Hell, Purvis,” Roadrunner hooted. “They ought to fire you and give that boy your job. All the Rangers and Tonto combined ain’t gonna catch him.”

Brogdon kept it up for another week, leaving more notes in more burglarized homes and tormenting the bloodhounds with trails of black pepper, while the posse grew increasingly nervous, the delighted chuckled, and the frightened moved their families to town. See More took them 60 miles west of Kerrville, but he finally got tired of it, checked into a hotel in Rocksprings, signed the register Charles Brogdon, and went upstairs to sleep. A twelve-year-old boy alerted the sheriff, who waited for reinforcements then ended the Kid’s reign of terror. Brogdon says some members of the arresting force expressed an interest in exacting some physical retribution, but Purvis held them off.

In jail Brogdon told officers if he had wanted to kill anybody he could have done so a dozen times, and he proved his point by showing them an x carved in a limb they had tracked beneath one evening. But burglary is burglary, and Brogdon got five years in prison for his misdeeds. He finished second in Prison Rodeo standings for the first time in 1955, and came back to Kerrville after 32 months. He ran into Purvis at a rodeo shortly after he got back, and the Kid’s old nemesis offered to get him on at the Y-O. “Purvis was a real nice fella,” Brogdon says today.

A Kerr County deputy sheriff, Jimmy Gibbs was foreman of the Y-O then. He remembers Brogdon as a good hand who generally kept to himself. “He was a fine bronc rider. I guess he was a pretty good old boy, but when he was drinking he got a little wild—he was part Indian, you know.”

Brogdon stayed at the Y-O for six months, and when he wasn’t working he often hung out at a beer joint on the Junction highway owned and operated by W. L. King and his wife Emma. King is a spry little man of 75 now and his joint is closed, but he remembers Brogdon as a favorite customer. He said Brogdon always occupied the same stool and sat quietly, picking at the label of his Lone Star, speaking only when spoken to.

“There never was anyone that came in my place that acted any nicer,” King said. “He wasn’t the kind of fella that walked around to the other tables poppin’ off about the things he’d done. He just sat and drank a little beer and minded his own business. I would never have known he was the See More Kid if someone else hadn’t told me.”

King seemed to be remembering a lot of things as he talked. “He borrowed money from us twice at least. On the day he said he’d pay it back, well, he was in there at the joint and he paid it. He owed us around four dollars and he was going to leave on Sunday for Oklahoma. He came in Saturday night and paid that bill. Most people would have left the country and said to heck with it.”

Brogdon apparently never made it to Oklahoma, however. He went to work for the Tom Burnett ranch in the mesquite country west of Wichita Falls, picking up extra change at small rodeos in Archer City, Burkburnett, and Vernon. Eventually he switched to the better pay of oilfield work, and in 1965 a vindictive judge sentenced him to two years in the Jones County jail in Anson for taking a $30 television set from a motel room. Anson has a gilded statue of the Republic’s second president on the courthouse square, and its most recent claim to fame is the cultural nurture of Jeannie C. Riley, who was so inspired by her home town that she sang The Harper Valley PTA. Anson is without doubt one of the bleaker stands of buildings in West Texas, and there’s no telling what the inside of the county jail looks like. Brogdon “got kinda discouraged,” and he and six other inmates overpowered a guard and broke jail.

Brogdon’s comrades took off in a car and were back in jail in no time, but the aging See More Kid took to the woods and walked to Abilene, 25 miles away. “February the eighth,” he told us. “I liked to froze to death.”

Brogdon escaped to California but after a year he came back and burglarized yet another residence in Fredericksburg, got arrested in Del Rio, and returned to prison in late 1966.

One more conviction in Texas and Brogdon will return to Huntsville as habitual criminal, a count that carries a mandatory life sentence. His record of arrests speaks for itself, and he has wasted a lot of Saturday nights behind bars, yet he remains one of the happier memories around Kerrville. When he’s an old man they’ll still remember him as that half-breed boy who made fools of the Texas Rangers.

The See More Kid’s warden sat quietly in the breeze of a fan during our interview, smiling occasionally. Brogdon is given to one-word sentences, and interviewing him is like trying to milk a Hereford cow. “Let’s see,” we asked provocatively, “there was an incident up in a canyon. . . ? They thought they had you trapped . . . ?

“Yeah. Canyon.”

We concluded the interview with the distinct impression we had talked to ourselves mostly, but we detected a certain glint of bemusement in Brogdon’s eyes as he recalled the episode. We wished him luck as we left, and he asked us to send him a copy of the article. We asked him where he was headed when he got out.

“Wyoming, Montana I guess. Maybe I could stay outa trouble up there.”

If there’s a mean streak in Charles Brogdon’s psychic makeup it’s not readily apparent. However, he does appear to have a rather casual disregard for the principle of private property, and the Lord knows where that kind of attitude will get you in the world today. Other than that, he’s just about as nice a fellow as you’ll ever talk to, just like they say. We hope he stays out of trouble this time, but if he does go on another tear in Montana, they’d better not let him get to the forest. There’s just no catching him.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Crime